TypeScript has become increasingly popular over the last few years, and many jobs are now requiring developers to know TypeScript.

But don't be alarmed – if you already know JavaScript, you will be able to pick up TypeScript quickly.

Even if you don't plan on using TypeScript, learning it will give you a better understanding of JavaScript – and make you a better developer.

In this article, you will learn:

- What is TypeScript and why should I learn it?

- How to set up a project with TypeScript

- All of the main TypeScript concepts (types, interfaces, generics, type-casting, and more...)

- How to use TypeScript with React

I also made a TypeScript cheat sheet PDF and poster that summarizes this article down to one page. This makes it easy to look up and revise concepts/syntax quickly.

What is TypeScript?

TypeScript is a superset of JavaScript, meaning that it does everything that JavaScript does, but with some added features.

The main reason for using TypeScript is to add static typing to JavaScript. Static typing means that the type of a variable cannot be changed at any point in a program. It can prevent a LOT of bugs!

On the other hand, JavaScript is a dynamically typed language, meaning variables can change type. Here's an example:

// JavaScript

let foo = "hello";

foo = 55; // foo has changed type from a string to a number - no problem

// TypeScript

let foo = "hello";

foo = 55; // ERROR - foo cannot change from string to number

TypeScript cannot be understood by browsers, so it has to be compiled into JavaScript by the TypeScript Compiler (TSC) – which we'll discuss soon.

Is TypeScript worth it?

Why you should use TypeScript

- Research has shown that TypeScript can spot 15% of common bugs.

- Readability – it is easier to see what the code it supposed to do. And when working in a team, it is easier to see what the other developers intended to.

- It's popular – knowing TypeScript will enable you to apply to more good jobs.

- Learning TypeScript will give you a better understanding, and a new perspective, on JavaScript.

Here's a short article I wrote demonstrating how TypeScript can prevent irritating bugs.

Drawbacks of TypeScript

- TypeScript takes longer to write than JavaScript, as you have to specify types, so for smaller solo projects it might not be worth using it.

- TypeScript has to be compiled – which can take time, especially in larger projects.

But the extra time that you have to spend writing more precise code and compiling will be more than saved by how many fewer bugs you'll have in your code.

For many projects – especially medium to large projects – TypeScript will save you lots of time and headaches.

And if you already know JavaScript, TypeScript won't be too hard to learn. It's a great tool to have in your arsenal.

How to Set Up a TypeScript Project

Install Node and the TypeScript Compiler

First, ensure you have Node installed globally on your machine.

Then install the TypeScript compiler globally on your machine by running the following command:

npm i -g typescript

To check if the installation is successful (it will return the version number if successful):

tsc -v

How to Compile TypeScript

Open up your text editor and create a TypeScript file (for example, index.ts).

Write some JavaScript or TypeScript:

let sport = 'football';

let id = 5;

We can now compile this down into JavaScript with the following command:

tsc index

TSC will compile the code into JavaScript and output it in a file called index.js:

var sport = 'football';

var id = 5;

If you want to specify the name of the output file:

tsc index.ts --outfile file-name.js

If you want TSC to compile your code automatically, whenever you make a change, add the "watch" flag:

tsc index.ts -w

An interesting thing about TypeScript is that it reports errors in your text editor whilst you are coding, but it will always compile your code – whether there are errors or not.

For example, the following causes TypeScript to immediately report an error:

var sport = 'football';

var id = 5;

id = '5'; // Error: Type 'string' is not assignable to

type 'number'.But if we try to compile this code with tsc index, the code will still compile, despite the error.

This is an important property of TypeScript: it assumes that the developer knows more. Even though there's a TypeScript error, it doesn't get in your way of compiling the code. It tells you there's an error, but it's up to you whether you do anything about it.

How to Set Up the ts config File

The ts config file should be in the root directory of your project. In this file we can specify the root files, compiler options, and how strict we want TypeScript to be in checking our project.

First, create the ts config file:

tsc --init

You should now have a tsconfig.json file in the project root.

Here are some options that are good to be aware of (if using a frontend framework with TypeScript, most if this stuff is taken care of for you):

{

"compilerOptions": {

...

/* Modules */

"target": "es2016", // Change to "ES2015" to compile to ES6

"rootDir": "./src", // Where to compile from

"outDir": "./public", // Where to compile to (usually the folder to be deployed to the web server)

/* JavaScript Support */

"allowJs": true, // Allow JavaScript files to be compiled

"checkJs": true, // Type check JavaScript files and report errors

/* Emit */

"sourceMap": true, // Create source map files for emitted JavaScript files (good for debugging)

"removeComments": true, // Don't emit comments

},

"include": ["src"] // Ensure only files in src are compiled

}

To compile everything and watch for changes:

tsc -w

Note: when input files are specified on the command line (for example, tsc index), tsconfig.json files are ignored.

Types in TypeScript

Primitive types

In JavaScript, a primitive value is data that is not an object and has no methods. There are 7 primitive data types:

- string

- number

- bigint

- boolean

- undefined

- null

- symbol

Primitives are immutable: they can't be altered. It is important not to confuse a primitive itself with a variable assigned a primitive value. The variable may be reassigned a new value, but the existing value can't be changed in the ways that objects, arrays, and functions can be altered.

Here's an example:

let name = 'Danny';

name.toLowerCase();

console.log(name); // Danny - the string method didn't mutate the string

let arr = [1, 3, 5, 7];

arr.pop();

console.log(arr); // [1, 3, 5] - the array method mutated the array

name = 'Anna' // Assignment gives the primitive a new (not a mutated) value

In JavaScript, all primitive values (apart from null and undefined) have object equivalents that wrap around the primitive values. These wrapper objects are String, Number, BigInt, Boolean, and Symbol. These wrapper objects provide the methods that allow the primitive values to be manipulated.

Back to TypeScript, we can set the type we want a variable to be be adding : type (called a "type annotation" or a "type signature") after declaring a variable. Examples:

let id: number = 5;

let firstname: string = 'danny';

let hasDog: boolean = true;

let unit: number; // Declare variable without assigning a value

unit = 5;

But it's usually best to not explicitly state the type, as TypeScript automatically infers the type of a variable (type inference):

let id = 5; // TS knows it's a number

let firstname = 'danny'; // TS knows it's a string

let hasDog = true; // TS knows it's a boolean

hasDog = 'yes'; // ERROR

We can also set a variable to be able to be a union type. A union type is a variable that can be assigned more than one type:

let age: string | number;

age = 26;

age = '26';

Reference Types

In JavaScript, almost "everything" is an object. In fact (and confusingly), strings, numbers and booleans can be objects if defined with the new keyword:

let firstname = new String('Danny');

console.log(firstname); // String {'Danny'}

But when we talk of reference types in JavaScript, we are referring to arrays, objects and functions.

Caveat: primitive vs reference types

For those that have never studied primitive vs reference types, let's discuss the fundamental difference.

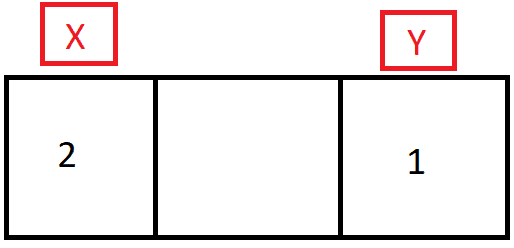

If a primitive type is assigned to a variable, we can think of that variable as containing the primitive value. Each primitive value is stored in a unique location in memory.

If we have two variables, x and y, and they both contain primitive data, then they are completely independent of each other:

let x = 2;

let y = 1;

x = y;

y = 100;

console.log(x); // 1 (even though y changed to 100, x is still 1)

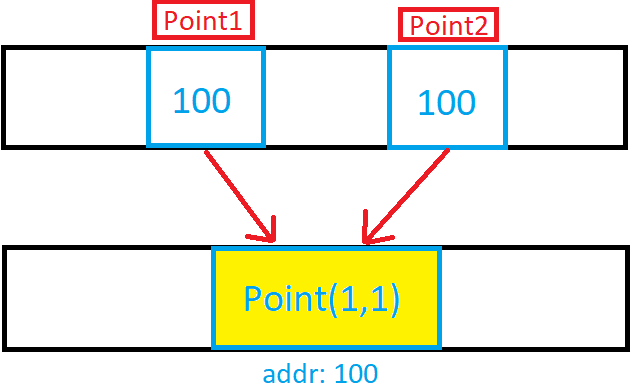

This isn't the case with reference types. Reference types refer to a memory location where the object is stored.

let point1 = { x: 1, y: 1 };

let point2 = point1;

point1.y = 100;

console.log(point2.y); // 100 (point1 and point2 refer to the same memory address where the point object is stored)

That was a quick overview of primary vs reference types. Check out this article if you need a more thorough explanation: Primitive vs reference types.

Arrays in TypeScript

In TypeScript, you can define what type of data an array can contain:

let ids: number[] = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; // can only contain numbers

let names: string[] = ['Danny', 'Anna', 'Bazza']; // can only contain strings

let options: boolean[] = [true, false, false]; can only contain true or false

let books: object[] = [

{ name: 'Fooled by randomness', author: 'Nassim Taleb' },

{ name: 'Sapiens', author: 'Yuval Noah Harari' },

]; // can only contain objects

let arr: any[] = ['hello', 1, true]; // any basically reverts TypeScript back into JavaScript

ids.push(6);

ids.push('7'); // ERROR: Argument of type 'string' is not assignable to parameter of type 'number'.You can use union types to define arrays containing multiple types:

let person: (string | number | boolean)[] = ['Danny', 1, true];

person[0] = 100;

person[1] = {name: 'Danny'} // Error - person array can't contain objectsIf you initialise a variable with a value, it's not necessary to explicitly state the type, as TypeScript will infer it:

let person = ['Danny', 1, true]; // This is identical to above example

person[0] = 100;

person[1] = { name: 'Danny' }; // Error - person array can't contain objectsThere is a special type of array that can be defined in TypeScript: Tuples. A tuple is an array with fixed size and known datatypes. They are stricter than regular arrays.

let person: [string, number, boolean] = ['Danny', 1, true];

person[0] = 100; // Error - Value at index 0 can only be a string

Objects in TypeScript

Objects in TypeScript must have all the correct properties and value types:

// Declare a variable called person with a specific object type annotation

let person: {

name: string;

location: string;

isProgrammer: boolean;

};

// Assign person to an object with all the necessary properties and value types

person = {

name: 'Danny',

location: 'UK',

isProgrammer: true,

};

person.isProgrammer = 'Yes'; // ERROR: should be a boolean

person = {

name: 'John',

location: 'US',

};

// ERROR: missing the isProgrammer propertyWhen defining the signature of an object, you will usually use an interface. This is useful if we need to check that multiple objects have the same specific properties and value types:

interface Person {

name: string;

location: string;

isProgrammer: boolean;

}

let person1: Person = {

name: 'Danny',

location: 'UK',

isProgrammer: true,

};

let person2: Person = {

name: 'Sarah',

location: 'Germany',

isProgrammer: false,

};

We can also declare function properties with function signatures. We can do this using old-school common JavaScript functions (sayHi), or ES6 arrow functions (sayBye):

interface Speech {

sayHi(name: string): string;

sayBye: (name: string) => string;

}

let sayStuff: Speech = {

sayHi: function (name: string) {

return `Hi ${name}`;

},

sayBye: (name: string) => `Bye ${name}`,

};

console.log(sayStuff.sayHi('Heisenberg')); // Hi Heisenberg

console.log(sayStuff.sayBye('Heisenberg')); // Bye Heisenberg

Note that in the sayStuff object, sayHi or sayBye could be given an arrow function or a common JavaScript function – TypeScript doesn't care.

Functions in TypeScript

We can define what the types the function arguments should be, as well as the return type of the function:

// Define a function called circle that takes a diam variable of type number, and returns a string

function circle(diam: number): string {

return 'The circumference is ' + Math.PI * diam;

}

console.log(circle(10)); // The circumference is 31.41592653589793The same function, but with an ES6 arrow function:

const circle = (diam: number): string => {

return 'The circumference is ' + Math.PI * diam;

};

console.log(circle(10)); // The circumference is 31.41592653589793Notice how it isn't necessary to explicitly state that circle is a function; TypeScript infers it. TypeScript also infers the return type of the function, so it doesn't need to be stated either. Although, if the function is large, some developers like to explicitly state the return type for clarity.

// Using explicit typing

const circle: Function = (diam: number): string => {

return 'The circumference is ' + Math.PI * diam;

};

// Inferred typing - TypeScript sees that circle is a function that always returns a string, so no need to explicitly state it

const circle = (diam: number) => {

return 'The circumference is ' + Math.PI * diam;

};We can add a question mark after a parameter to make it optional. Also notice below how c is a union type that can be a number or string:

const add = (a: number, b: number, c?: number | string) => {

console.log(c);

return a + b;

};

console.log(add(5, 4, 'I could pass a number, string, or nothing here!'));

// I could pass a number, string, or nothing here!

// 9

A function that returns nothing is said to return void – a complete lack of any value. Below, the return type of void has been explicitly stated. But again, this isn't necessary as TypeScript will infer it.

const logMessage = (msg: string): void => {

console.log('This is the message: ' + msg);

};

logMessage('TypeScript is superb'); // This is the message: TypeScript is superbIf we want to declare a function variable, but not define it (say exactly what it does), then use a function signature. Below, the function sayHello must follow the signature after the colon:

// Declare the varible sayHello, and give it a function signature that takes a string and returns nothing.

let sayHello: (name: string) => void;

// Define the function, satisfying its signature

sayHello = (name) => {

console.log('Hello ' + name);

};

sayHello('Danny'); // Hello Danny

Here's an interactive scrim to help you learn more about functions in TypeScript:

Dynamic (any) types

Using the any type, we can basically revert TypeScript back into JavaScript:

let age: any = '100';

age = 100;

age = {

years: 100,

months: 2,

};

It's recommended to avoid using the any type as much as you can, as it prevents TypeScript from doing its job – and can lead to bugs.

Type Aliases

Type Aliases can reduce code duplication, keeping our code DRY. Below, we can see that the PersonObject type alias has prevented repetition, and acts as a single source of truth for what data a person object should contain.

type StringOrNumber = string | number;

type PersonObject = {

name: string;

id: StringOrNumber;

};

const person1: PersonObject = {

name: 'John',

id: 1,

};

const person2: PersonObject = {

name: 'Delia',

id: 2,

};

const sayHello = (person: PersonObject) => {

return 'Hi ' + person.name;

};

const sayGoodbye = (person: PersonObject) => {

return 'Seeya ' + person.name;

};

The DOM and type casting

TypeScript doesn't have access to the DOM like JavaScript. This means that whenever we try to access DOM elements, TypeScript is never sure that they actually exist.

The below example shows the problem:

const link = document.querySelector('a');

console.log(link.href); // ERROR: Object is possibly 'null'. TypeScript can't be sure the anchor tag exists, as it can't access the DOMWith the non-null assertion operator (!) we can tell the compiler explicitly that an expression has value other than null or undefined. This is can be useful when the compiler cannot infer the type with certainty, but we have more information than the compiler.

// Here we are telling TypeScript that we are certain that this anchor tag exists

const link = document.querySelector('a')!;

console.log(link.href); // www.freeCodeCamp.orgNotice how we didn't have to state the type of the link variable. This is because TypeScript can clearly see (via Type Inference) that it is of type HTMLAnchorElement.

But what if we needed to select a DOM element by its class or id? TypeScript can't infer the type, as it could be anything.

const form = document.getElementById('signup-form');

console.log(form.method);

// ERROR: Object is possibly 'null'.

// ERROR: Property 'method' does not exist on type 'HTMLElement'.

Above, we get two errors. We need to tell TypeScript that we are certain form exists, and that we know it is of type HTMLFormElement. We do this with type casting:

const form = document.getElementById('signup-form') as HTMLFormElement;

console.log(form.method); // postAnd TypeScript is happy!

TypeScript also has an Event object built in. So, if we add a submit event listener to our form, TypeScript will give us an error if we call any methods that aren't part of the Event object. Check out how cool TypeScript is – it can tell us when we've made a spelling mistake:

const form = document.getElementById('signup-form') as HTMLFormElement;

form.addEventListener('submit', (e: Event) => {

e.preventDefault(); // prevents the page from refreshing

console.log(e.tarrget); // ERROR: Property 'tarrget' does not exist on type 'Event'. Did you mean 'target'?

});

Here's an interactive scrim to help you learn more about types in TypeScript:

Classes in TypeScript

We can define the types that each piece of data should be in a class:

class Person {

name: string;

isCool: boolean;

pets: number;

constructor(n: string, c: boolean, p: number) {

this.name = n;

this.isCool = c;

this.pets = p;

}

sayHello() {

return `Hi, my name is ${this.name} and I have ${this.pets} pets`;

}

}

const person1 = new Person('Danny', false, 1);

const person2 = new Person('Sarah', 'yes', 6); // ERROR: Argument of type 'string' is not assignable to parameter of type 'boolean'.

console.log(person1.sayHello()); // Hi, my name is Danny and I have 1 petsWe could then create a people array that only includes objects constructed from the Person class:

let People: Person[] = [person1, person2];We can add access modifiers to the properties of a class. TypeScript also provides a new access modifier called readonly.

class Person {

readonly name: string; // This property is immutable - it can only be read

private isCool: boolean; // Can only access or modify from methods within this class

protected email: string; // Can access or modify from this class and subclasses

public pets: number; // Can access or modify from anywhere - including outside the class

constructor(n: string, c: boolean, e: string, p: number) {

this.name = n;

this.isCool = c;

this.email = e;

this.pets = p;

}

sayMyName() {

console.log(`Your not Heisenberg, you're ${this.name}`);

}

}

const person1 = new Person('Danny', false, 'dan@e.com', 1);

console.log(person1.name); // Fine

person1.name = 'James'; // Error: read only

console.log(person1.isCool); // Error: private property - only accessible within Person class

console.log(person1.email); // Error: protected property - only accessible within Person class and its subclasses

console.log(person1.pets); // Public property - so no problemWe can make our code more concise by constructing class properties this way:

class Person {

constructor(

readonly name: string,

private isCool: boolean,

protected email: string,

public pets: number

) {}

sayMyName() {

console.log(`Your not Heisenberg, you're ${this.name}`);

}

}

const person1 = new Person('Danny', false, 'dan@e.com', 1);

console.log(person1.name); // Danny

Writing it the above way, the properties are automatically assigned in the constructor – saving us from having to write them all out.

Note that if we omit the access modifier, by default the property will be public.

Classes can also be extended, just like in regular JavaScript:

class Programmer extends Person {

programmingLanguages: string[];

constructor(

name: string,

isCool: boolean,

email: string,

pets: number,

pL: string[]

) {

// The super call must supply all parameters for base (Person) class, as the constructor is not inherited.

super(name, isCool, email, pets);

this.programmingLanguages = pL;

}

}For more on classes, refer to the official TypeScript docs.

Here's an interactive scrim to help you learn more about classes in TypeScript:

Modules in TypeScript

In JavaScript, a module is just a file containing related code. Functionality can be imported and exported between modules, keeping the code well organized.

TypeScript also supports modules. The TypeScript files will compile down into multiple JavaScript files.

In the tsconfig.json file, change the following options to support modern importing and exporting:

"target": "es2016",

"module": "es2015"(Although, for Node projects you very likely want "module": "CommonJS" – Node doesn't yet support modern importing/exporting.)

Now, in your HTML file, change the script import to be of type module:

<script type="module" src="/public/script.js"></script>

We can now import and export files using ES6:

// src/hello.ts

export function sayHi() {

console.log('Hello there!');

}

// src/script.ts

import { sayHi } from './hello.js';

sayHi(); // Hello there!

Note: always import as a JavaScript file, even in TypeScript files.

Interfaces in TypeScript

Interfaces define how an object should look:

interface Person {

name: string;

age: number;

}

function sayHi(person: Person) {

console.log(`Hi ${person.name}`);

}

sayHi({

name: 'John',

age: 48,

}); // Hi John

You can also define an object type using a type alias:

type Person = {

name: string;

age: number;

};

function sayHi(person: Person) {

console.log(`Hi ${person.name}`);

}

sayHi({

name: 'John',

age: 48,

}); // Hi JohnOr an object type could be defined anonymously:

function sayHi(person: { name: string; age: number }) {

console.log(`Hi ${person.name}`);

}

sayHi({

name: 'John',

age: 48,

}); // Hi John

Interfaces are very similar to type aliases, and in many cases you can use either. The key distinction is that type aliases cannot be reopened to add new properties, vs an interface which is always extendable.

The following examples are taken from the TypeScript docs.

Extending an interface:

interface Animal {

name: string

}

interface Bear extends Animal {

honey: boolean

}

const bear: Bear = {

name: "Winnie",

honey: true,

}Extending a type via intersections:

type Animal = {

name: string

}

type Bear = Animal & {

honey: boolean

}

const bear: Bear = {

name: "Winnie",

honey: true,

}Adding new fields to an existing interface:

interface Animal {

name: string

}

// Re-opening the Animal interface to add a new field

interface Animal {

tail: boolean

}

const dog: Animal = {

name: "Bruce",

tail: true,

}Here's the key difference: a type cannot be changed after being created:

type Animal = {

name: string

}

type Animal = {

tail: boolean

}

// ERROR: Duplicate identifier 'Animal'.As a rule of thumb, the TypeScript docs recommend using interfaces to define objects, until you need to use the features of a type.

Interfaces can also define function signatures:

interface Person {

name: string

age: number

speak(sentence: string): void

}

const person1: Person = {

name: "John",

age: 48,

speak: sentence => console.log(sentence),

}You may be wondering why we would use an interface over a class in the above example.

One advantage of using an interface is that it is only used by TypeScript, not JavaScript. This means that it won't get compiled and add bloat to your JavaScript. Classes are features of JavaScript, so it would get compiled.

Also, a class is essentially an object factory (that is, a blueprint of what an object is supposed to look like and then implemented), whereas an interface is a structure used solely for type-checking.

While a class may have initialized properties and methods to help create objects, an interface essentially defines the properties and type an object can have.

Interfaces with classes

We can tell a class that it must contain certain properties and methods by implementing an interface:

interface HasFormatter {

format(): string;

}

class Person implements HasFormatter {

constructor(public username: string, protected password: string) {}

format() {

return this.username.toLocaleLowerCase();

}

}

// Must be objects that implement the HasFormatter interface

let person1: HasFormatter;

let person2: HasFormatter;

person1 = new Person('Danny', 'password123');

person2 = new Person('Jane', 'TypeScripter1990');

console.log(person1.format()); // dannyEnsure that people is an array of objects that implement HasFormatter (ensures that each person has the format method):

let people: HasFormatter[] = [];

people.push(person1);

people.push(person2);Literal types in TypeScript

In addition to the general types string and number, we can refer to specific strings and numbers in type positions:

// Union type with a literal type in each position

let favouriteColor: 'red' | 'blue' | 'green' | 'yellow';

favouriteColor = 'blue';

favouriteColor = 'crimson'; // ERROR: Type '"crimson"' is not assignable to type '"red" | "blue" | "green" | "yellow"'.Here's an interactive scrim to help you learn more about literal types in TypeScript:

Generics

Generics allow you to create a component that can work over a variety of types, rather than a single one, which helps to make the component more reusable.

Let's go through an example to show you what that means...

The addID function accepts any object, and returns a new object with all the properties and values of the passed in object, plus an id property with random value between 0 and 1000. In short, it gives any object an ID.

const addID = (obj: object) => {

let id = Math.floor(Math.random() * 1000);

return { ...obj, id };

};

let person1 = addID({ name: 'John', age: 40 });

console.log(person1.id); // 271

console.log(person1.name); // ERROR: Property 'name' does not exist on type '{ id: number; }'.

As you can see, TypeScript gives an error when we try to access the name property. This is because when we pass in an object to addID, we are not specifying what properties this object should have – so TypeScript has no idea what properties the object has (it hasn't "captured" them). So, the only property that TypeScript knows is on the returned object is id.

So, how can we pass in any object to addID, but still tell TypeScript what properties and values the object has? We can use a generic, <T> – where T is known as the type parameter:

// <T> is just the convention - e.g. we could use <X> or <A>

const addID = <T>(obj: T) => {

let id = Math.floor(Math.random() * 1000);

return { ...obj, id };

};What does this do? Well, now when we pass an object into addID, we have told TypeScript to capture the type – so T becomes whatever type we pass in. addID will now know what properties are on the object we pass in.

But, we now have a problem: anything can be passed into addID and TypeScript will capture the type and report no problem:

let person1 = addID({ name: 'John', age: 40 });

let person2 = addID('Sally'); // Pass in a string - no problem

console.log(person1.id); // 271

console.log(person1.name); // John

console.log(person2.id);

console.log(person2.name); // ERROR: Property 'name' does not exist on type '"Sally" & { id: number; }'.When we passed in a string, TypeScript saw no issue. It only reported an error when we tried to access the name property. So, we need a constraint: we need to tell TypeScript that only objects should be accepted, by making our generic type, T, an extension of object:

const addID = <T extends object>(obj: T) => {

let id = Math.floor(Math.random() * 1000);

return { ...obj, id };

};

let person1 = addID({ name: 'John', age: 40 });

let person2 = addID('Sally'); // ERROR: Argument of type 'string' is not assignable to parameter of type 'object'.The error is caught straight away – perfect... well, not quite. In JavaScript, arrays are objects, so we can still get away with passing in an array:

let person2 = addID(['Sally', 26]); // Pass in an array - no problem

console.log(person2.id); // 824

console.log(person2.name); // Error: Property 'name' does not exist on type '(string | number)[] & { id: number; }'.We could solve this by saying that the object argument should have a name property with string value:

const addID = <T extends { name: string }>(obj: T) => {

let id = Math.floor(Math.random() * 1000);

return { ...obj, id };

};

let person2 = addID(['Sally', 26]); // ERROR: argument should have a name property with string valueThe type can also be passed in to <T>, as below – but this isn't necessary most of the time, as TypeScript will infer it.

// Below, we have explicitly stated what type the argument should be between the angle brackets.

let person1 = addID<{ name: string; age: number }>({ name: 'John', age: 40 });Generics allow you to have type-safety in components where the arguments and return types are unknown ahead of time.

In TypeScript, generics are used when we want to describe a correspondence between two values. In the above example, the return type was related to the input type. We used a generic to describe the correspondence.

Another example: If we need a function that accepts multiple types, it is better to use a generic than the any type. Below shows the issue with using any:

function logLength(a: any) {

console.log(a.length); // No error

return a;

}

let hello = 'Hello world';

logLength(hello); // 11

let howMany = 8;

logLength(howMany); // undefined (but no TypeScript error - surely we want TypeScript to tell us we've tried to access a length property on a number!)We could try using a generic:

function logLength<T>(a: T) {

console.log(a.length); // ERROR: TypeScript isn't certain that `a` is a value with a length property

return a;

}At least we are now getting some feedback that we can use to tighten up our code.

Solution: use a generic that extends an interface that ensures every argument passed in has a length property:

interface hasLength {

length: number;

}

function logLength<T extends hasLength>(a: T) {

console.log(a.length);

return a;

}

let hello = 'Hello world';

logLength(hello); // 11

let howMany = 8;

logLength(howMany); // Error: numbers don't have length propertiesWe could also write a function where the argument is an array of elements that all have a length property:

interface hasLength {

length: number;

}

function logLengths<T extends hasLength>(a: T[]) {

a.forEach((element) => {

console.log(element.length);

});

}

let arr = [

'This string has a length prop',

['This', 'arr', 'has', 'length'],

{ material: 'plastic', length: 30 },

];

logLengths(arr);

// 29

// 4

// 30Generics are an awesome feature of TypeScript!

Generics with interfaces

When we don't know what type a certain value in an object will be ahead of time, we can use a generic to pass in the type:

// The type, T, will be passed in

interface Person<T> {

name: string;

age: number;

documents: T;

}

// We have to pass in the type of `documents` - an array of strings in this case

const person1: Person<string[]> = {

name: 'John',

age: 48,

documents: ['passport', 'bank statement', 'visa'],

};

// Again, we implement the `Person` interface, and pass in the type for documents - in this case a string

const person2: Person<string> = {

name: 'Delia',

age: 46,

documents: 'passport, P45',

};Enums in TypeScript

Enums are a special feature that TypeScript brings to JavaScript. Enums allow us to define or declare a collection of related values, that can be numbers or strings, as a set of named constants.

enum ResourceType {

BOOK,

AUTHOR,

FILM,

DIRECTOR,

PERSON,

}

console.log(ResourceType.BOOK); // 0

console.log(ResourceType.AUTHOR); // 1

// To start from 1

enum ResourceType {

BOOK = 1,

AUTHOR,

FILM,

DIRECTOR,

PERSON,

}

console.log(ResourceType.BOOK); // 1

console.log(ResourceType.AUTHOR); // 2By default, enums are number based – they store string values as numbers. But they can also be strings:

enum Direction {

Up = 'Up',

Right = 'Right',

Down = 'Down',

Left = 'Left',

}

console.log(Direction.Right); // Right

console.log(Direction.Down); // DownEnums are useful when we have a set of related constants. For example, instead of using non-descriptive numbers throughout your code, enums make code more readable with descriptive constants.

Enums can also prevent bugs, as when you type the name of the enum, intellisense will pop up and give you the list of possible options that can be selected.

TypeScript strict mode

It is recommended to have all strict type-checking operations enabled in the tsconfig.json file. This will cause TypeScript to report more errors, but will help prevent many bugs from creeping into your application.

// tsconfig.json

"strict": trueLet's discuss a couple of the things that strict mode does: no implicit any, and strict null checks.

No implicit any

In the function below, TypeScript has inferred that the parameter a is of any type. As you can see, when we pass in a number to this function, and try to log a name property, no error is reported. Not good.

function logName(a) {

// No error??

console.log(a.name);

}

logName(97);With the noImplicitAny option turned on, TypeScript will instantly flag an error if we don't explicitly state the type of a:

// ERROR: Parameter 'a' implicitly has an 'any' type.

function logName(a) {

console.log(a.name);

}Strict null checks

When the strictNullChecks option is false, TypeScript effectively ignores null and undefined. This can lead to unexpected errors at runtime.

With strictNullChecks set to true, null and undefined have their own types, and you'll get a type error if you assign them to a variable that expects a concrete value (for example, string).

let whoSangThis: string = getSong();

const singles = [

{ song: 'touch of grey', artist: 'grateful dead' },

{ song: 'paint it black', artist: 'rolling stones' },

];

const single = singles.find((s) => s.song === whoSangThis);

console.log(single.artist);

Above, singles.find has no guarantee that it will find the song – but we have written the code as though it always will.

By setting strictNullChecks to true, TypeScript will raise an error because we haven't made a guarantee that single exists before trying to use it:

const getSong = () => {

return 'song';

};

let whoSangThis: string = getSong();

const singles = [

{ song: 'touch of grey', artist: 'grateful dead' },

{ song: 'paint it black', artist: 'rolling stones' },

];

const single = singles.find((s) => s.song === whoSangThis);

console.log(single.artist); // ERROR: Object is possibly 'undefined'.TypeScript is basically telling us to ensure single exists before using it. We need to check if it isn't null or undefined first:

if (single) {

console.log(single.artist); // rolling stones

}

Narrowing in TypeScript

In a TypeScript program, a variable can move from a less precise type to a more precise type. This process is called type narrowing.

Here's a simple example showing how TypeScript narrows down the less specific type of string | number to more specific types when we use if-statements with typeof:

function addAnother(val: string | number) {

if (typeof val === 'string') {

// TypeScript treats `val` as a string in this block, so we can use string methods on `val` and TypeScript won't shout at us

return val.concat(' ' + val);

}

// TypeScript knows `val` is a number here

return val + val;

}

console.log(addAnother('Woooo')); // Woooo Woooo

console.log(addAnother(20)); // 40

Another example: below, we have defined a union type called allVehicles, which can either be of type Plane or Train.

interface Vehicle {

topSpeed: number;

}

interface Train extends Vehicle {

carriages: number;

}

interface Plane extends Vehicle {

wingSpan: number;

}

type PlaneOrTrain = Plane | Train;

function getSpeedRatio(v: PlaneOrTrain) {

// In here, we want to return topSpeed/carriages, or topSpeed/wingSpan

console.log(v.carriages); // ERROR: 'carriages' doesn't exist on type 'Plane'

}

Since the function getSpeedRatio is working with multiple types, we need a way of distinguishing whether v is a Plane or Train. We could do this by giving both types a common distinguishing property, with a literal string value:

// All trains must now have a type property equal to 'Train'

interface Train extends Vehicle {

type: 'Train';

carriages: number;

}

// All trains must now have a type property equal to 'Plane'

interface Plane extends Vehicle {

type: 'Plane';

wingSpan: number;

}

type PlaneOrTrain = Plane | Train;Now we, and TypeScript, can narrow down the type of v:

function getSpeedRatio(v: PlaneOrTrain) {

if (v.type === 'Train') {

// TypeScript now knows that `v` is definitely a `Train`. It has narrowed down the type from the less specific `Plane | Train` type, into the more specific `Train` type

return v.topSpeed / v.carriages;

}

// If it's not a Train, TypeScript narrows down that `v` must be a Plane - smart!

return v.topSpeed / v.wingSpan;

}

let bigTrain: Train = {

type: 'Train',

topSpeed: 100,

carriages: 20,

};

console.log(getSpeedRatio(bigTrain)); // 5Bonus: TypeScript with React

TypeScript has full support for React and JSX. This means we can use TypeScript with the three most common React frameworks:

If you require a more custom React-TypeScript configuration, you could setup Webpack (a module bundler) and configure the tsconfig.json yourself. But most of the time, a framework will do the job.

To setup up create-react-app with TypeScript, for example, simply run:

npx create-react-app my-app --template typescript

# or

yarn create react-app my-app --template typescriptIn the src folder, we can now create files with .ts (for regular TypeScript files) or .tsx (for TypeScript with React) extensions and write our components with TypeScript. This will then compile down into JavaScript in the public folder.

React props with TypeScript

Below, we are saying that Person should be a React functional component that accepts a props object with the props name, which should be a string, and age, which should be a number.

// src/components/Person.tsx

import React from 'react';

const Person: React.FC<{

name: string;

age: number;

}> = ({ name, age }) => {

return (

<div>

<div>{name}</div>

<div>{age}</div>

</div>

);

};

export default Person;

But most developers prefer to use an interface to specify prop types:

interface Props {

name: string;

age: number;

}

const Person: React.FC<Props> = ({ name, age }) => {

return (

<div>

<div>{name}</div>

<div>{age}</div>

</div>

);

};We can then import this component into App.tsx. If we don't provide the necessary props, TypeScript will give an error.

import React from 'react';

import Person from './components/Person';

const App: React.FC = () => {

return (

<div>

<Person name='John' age={48} />

</div>

);

};

export default App;

Here are a few examples for what we could have as prop types:

interface PersonInfo {

name: string;

age: number;

}

interface Props {

text: string;

id: number;

isVeryNice?: boolean;

func: (name: string) => string;

personInfo: PersonInfo;

}React hooks with TypeScript

useState()

We can declare what types a state variable should be by using angle brackets. Below, if we omitted the angle brackets, TypeScript would infer that cash is a number. So, if want to enable it to also be null, we have to specify:

const Person: React.FC<Props> = ({ name, age }) => {

const [cash, setCash] = useState<number | null>(1);

setCash(null);

return (

<div>

<div>{name}</div>

<div>{age}</div>

</div>

);

};useRef()

useRef returns a mutable object that persists for the lifetime of the component. We can tell TypeScript what the ref object should refer to – below we say the prop should be a HTMLInputElement:

const Person: React.FC = () => {

// Initialise .current property to null

const inputRef = useRef<HTMLInputElement>(null);

return (

<div>

<input type='text' ref={inputRef} />

</div>

);

};For more information on React with TypeScript, checkout these awesome React-TypeScript cheatsheets.

Useful resources & further reading

- The official TypeScript docs

- The Net Ninja's TypeScript video series (awesome!)

- Ben Awad's TypeScript with React video

- Narrowing in TypeScript (a very interesting feature of TS that you should learn)

- Function overloads

- Primitive values in JavaScript

- JavaScript objects

Thanks for reading!

Hope that was useful. If you made it to here, you now know the main fundamentals of TypeScript and can start using it in your projects.

Again, you can also download my one-page TypeScript cheat sheet PDF or order a physical poster.

For more from me, you can find me on Twitter and YouTube.

Cheers!