By Nadeesha Cabral

Functional programming is great. With the introduction of React, more and more JavaScript front-end code is being written with FP principles in mind. But how do we start using the FP mindset in everyday code we write? I’ll attempt to use an everyday code block and refactor it step by step.

Our problem: A user who comes to our /login page will optionally have a redirect_to query parameter. Like /login?redirect_to=%2Fmy-page. Note that %2Fmy-page is actually /my-page when it’s encoded as the part of the URL. We need to extract this query string, and store it in local storage, so that once the login is done, user can be redirected to the my-page.

Step #0: The imperative approach

If we had to express the solution in the simplest form of issuing a list of commands, how would we write it? We will need to

- Parse the query string.

- Get the

redirect_tovalue. - Decode that value.

- Store the decoded value in localStorage.

And we have to put try catch blocks around “unsafe” functions as well. With all of that, our code block will look like:

Step #1: Writing every step as a function

For a moment, let’s forget the try catch blocks and try expressing everything as a function here.

When we start expressing all of our “outcomes” as results of functions, we see what we can refactor out of our main function body. When that happens, our function becomes much easier to grok, and much easier to test.

Earlier, we would have tested the main function as a whole. But now, we have 4 smaller functions, and some of them are just proxying other functions, so the footprint that needs to be tested is much smaller.

Let’s identify these proxying functions, and remove the proxy, so we have a little bit less code.

Step #2: An attempt at composing functions

Alright. Now, it seems like the persistRedirectToParams function is a “composition” of 4 other functions. Let’s see whether we can write this function as a composition, thereby eliminating the interim results we store as consts.

This is good. But I feel for the person who reads this nested function call. If there was a way to untangle this mess, that’d be awesome.

Step #3: A more readable composition

If you’ve done some redux or recompose, you’d have come across compose. Compose is a utility function which accepts multiple functions, and returns one function that calls the underlying functions one by one. There are other excellent sources to learn about composition, so I won’t go into detail about that here.

With compose, our code will look like:

One thing with compose is that it reduces functions right-to-left. So, the first function that gets invoked in the compose chain is the last function.

This is not a problem if you’re a mathematician, and are familiar with the concept, so you naturally read this right-to-left. But for the rest of us familiar with imperative code, we would like to read this left-to-right.

Step #4: Piping and flattening

Luckily, there’s pipe. pipe does the same thing that compose does, but in reverse. So, the first function in the chain is the first function processing the result.

Also, it seems as if our persistRedirectToParams function has become a wrapper for another function that we call op. In other words, all it does is execute op. We can get rid of the wrapper and “flatten” our function.

Almost there. Remember, that we conveniently left our try-catch block behind to get this to the current state? Well, we need some way to introduce it back. qs.parse is unsafe as well as storeRedirectToQuery. One option is to make them wrapper functions and put them in try-catch blocks. The other, functional way is to express try-catch as a function.

Step #5: Exception handling as a function

There are some utilities which do this, but let’s try writing something ourselves.

Our function here expects an opts object which will contain tryer and catcher functions. It will return a function which, when invoked with arguments, call the tryer with the said arguments and upon failure, call the catcher. Now, when we have unsafe operations, we can put them in the tryer section and if they fail, rescue and give a safe result from the catcher section (and even log the error).

Step #6: Putting everything together

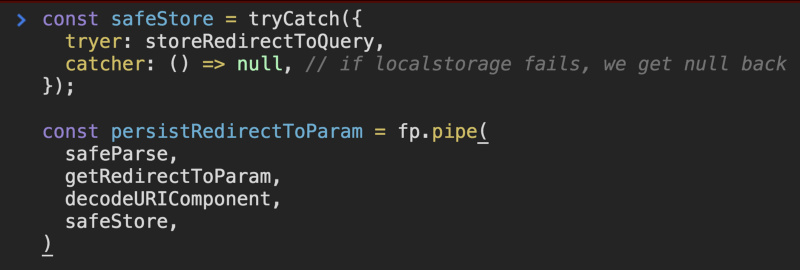

So, with that in mind, our final code looks like:

This is more or less what we want. But to make sure the readability and testability of our code improves, we can factor out the “safe” functions as well.

Now, what we’ve got is an implementation of a much larger function, consisting of 4 individual functions that are highly cohesive, loosely coupled, can be tested independently, can be re-used independently, account for exception scenarios, and are highly declarative. (And IMO, they’re a tad bit nicer to read.)

There’s some FP syntactic sugar that makes this even nicer, but that’s for another day.