By Fredrik Strand Oseberg

When does an asynchronous function finish? And why is this such a hard question to answer?

Well it turns out that understanding asynchronous functions requires a great deal of knowledge about how JavaScript works fundamentally.

Let's go explore this concept, and learn a lot about JavaScript in the process.

Are you ready? Let's go.

What is asynchronous code?

By design, JavaScript is a synchronous programming language. This means that when code is executed, JavaScript starts at the top of the file and runs through code line by line, until it is done.

The result of this design decision is that only one thing can happen at any one time.

You can think of this as if you were juggling six small balls. While you are juggling, your hands are occupied and can't handle anything else.

It's the same with JavaScript: once the code is running, it has its hands full with that code. We call this this kind of synchronous code blocking. Because it's effectively blocking other code from running.

Let's circle back to the juggling example. What would happen if you wanted to add another ball? Instead of six balls, you wanted to juggle seven balls. That's might be a problem.

You don't want to stop juggling, because it's just so much fun. But you can't go and get another ball either, because that would mean you'd have to stop.

The solution? Delegate the work to a friend or family member. They aren't juggling, so they can go and get the ball for you, then toss it into your juggling at a time when your hand is free and you are ready to add another ball mid-juggle.

This is what asynchronous code is. JavaScript is delegating the work to something else, then going about it's own business. Then when it's ready, it will receive the results back from the work.

Who is doing the other work?

Alright, so we know that JavaScript is synchronous and lazy. It doesn't want to do all of the work itself, so it farms it out to something else.

But who is this mysterious entity that works for JavaScript? And how does it get hired to work for JavaScript?

Well, let's take a look at an example of asynchronous code.

const logName = () => {

console.log("Han")

}

setTimeout(logName, 0)

console.log("Hi there")

Running this code results in the following output in the console:

// in console

Hi there

Han

Alright. What is going on?

It turns out that the way we farm out work in JavaScript is to use environment-specific functions and APIs. And this is a source of great confusion in JavaScript.

JavaScript always runs in an environment.

Often, that environment is the browser. But it can also be on the server with NodeJS. But what on earth is the difference?

The difference – and this is important – is that the browser and the server (NodeJS), functionality-wise, are not equivalent. They are often similar, but they are not the same.

Let's illustrate this with an example. Let's say JavaScript is the protagonist of an epic fantasy book. Just an ordinary farm kid.

Now let's say that this farm kid found two suits of special armor that gave them powers beyond their own.

When they used the browser suit of armor, they gained access to a certain set of capabilities.

When they used the server suit of armor they gained access to another set of capabilities.

These suits have some overlap, because the creators of these suits had the same needs in certain places, but not in others.

This is what an environment is. A place where code is run, where there exist tools that are built on top of the existing JavaScript language. They are not a part of the language, but the line is often blurred because we use these tools every day when we write code.

setTimeout, fetch, and DOM are all examples of Web APIs. (You can see the full list of Web APIs here.) They are tools that are built into the browser, and that are made available to us when our code is run.

And because we always run JavaScript in an environment, it seems like these are part of the language. But they are not.

So if you've ever wondered why you can use fetch in JavaScript when you run it in the browser (but need to install a package when you run it in NodeJS), this is why. Someone thought fetch was a good idea, and built it as a tool for the NodeJS environment.

Confusing? Yes!

But now we can finally understand what takes on the work from JavaScript, and how it gets hired.

It turns out that it is the environment that takes on the work, and the way to get the environment to do that work, is to use functionality that belongs to the environment. For example fetch or setTimeout in the browser environment.

What happens to the work?

Great. So the environment takes on the work. Then what?

At some point you need to get the results back. But let's think about how this would work.

Let's go back to the juggling example from the beginning. Imagine you asked for a new ball, and a friend just started throwing the ball at you when you weren't ready.

That would be a disaster. Maybe you could get lucky and catch it and get it into your routine effectively. But theres a large chance that it may cause you to drop all of your balls and crash your routine. Wouldn't it be better if you gave strict instructions on when to receive the ball?

As it turns out, there are strict rules surrounding when JavaScript can receive delegated work.

Those rules are governed by the event loop and involve the microtask and macrotask queue. Yes, I know. It's a lot. But bear with me.

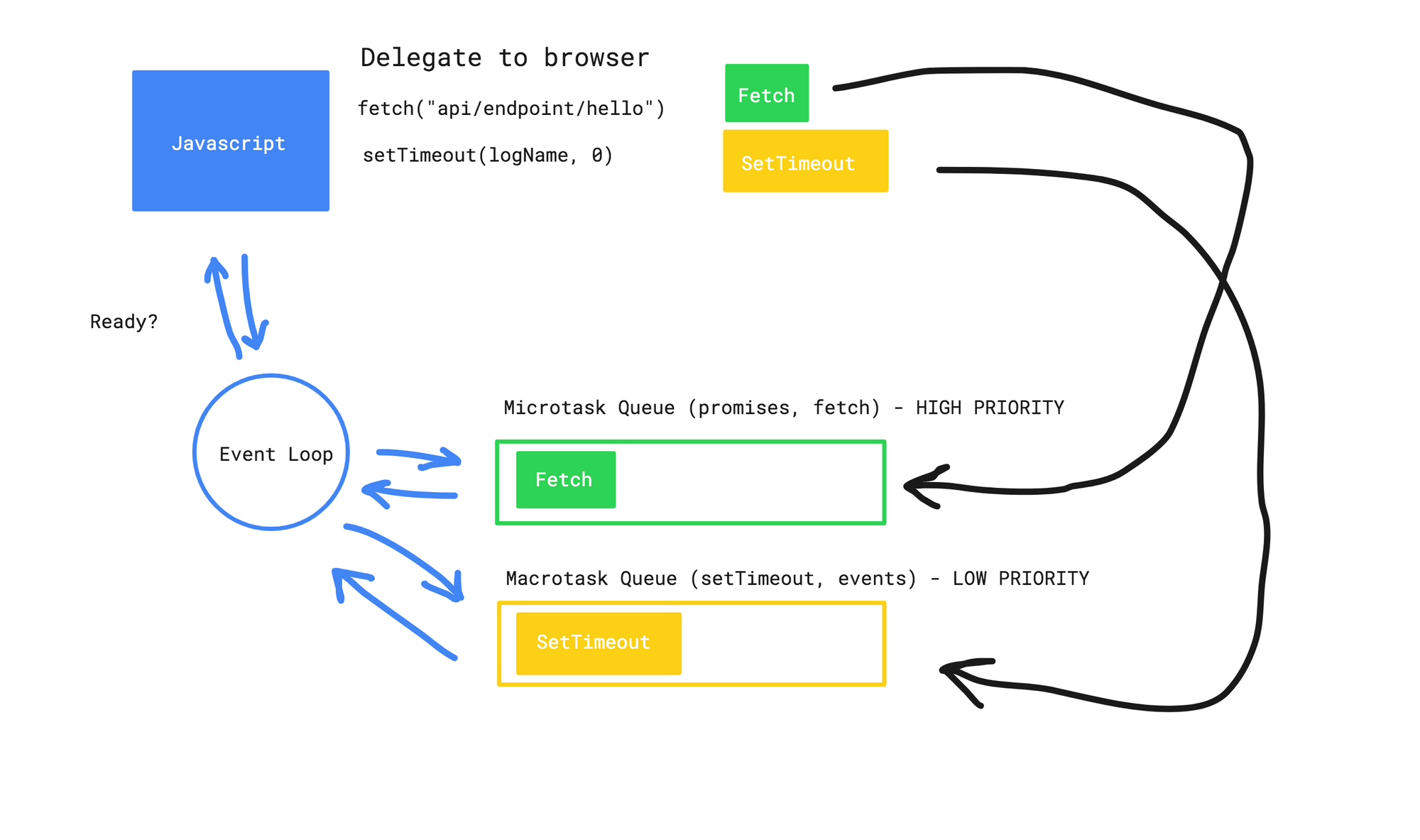

Alright. So when we delegate asynchronous code to the browser, the browser takes and runs the code and takes on that workload. But there may be multiple tasks that are given to the browser, so we need to make sure that we can prioritise these tasks.

This is where the microtask queue and the macrotask queue come in play. The browser will take the work, do it, then place the result in one of the two queues based on the type of work it receives.

Promises, for example, are placed in the microtask queue and have a higher priority.

Events and setTimeout are examples of work that is put in the macrotask queue, and have a lower priority.

Now once the work is done, and is placed in one of the two queues, the event loop will run back and forth and check whether or not JavaScript is ready to receive the results.

Only when JavaScript is done running all its synchronous code, and is good and ready, will the event loop start picking from the queues and handing the functions back to JavaScript to run.

So let's take a look at an example:

setTimeout(() => console.log("hello"), 0)

fetch("https://someapi/data").then(response => response.json())

.then(data => console.log(data))

console.log("What soup?")

What will the order be here?

- Firstly, setTimeout is delegated to the browser, which does the work and puts the resulting function in the macrotask queue.

- Secondly fetch is delegated to the browser, which takes the work. It retrieves the data from the endpoint and puts the resulting functions in the microtask queue.

- Javascript logs out "What soup"?

- The event loop checks whether or not JavaScript is ready to receive the results from the queued work.

- When the console.log is done, JavaScript is ready. The event loop picks queued functions from the microtask queue, which has a higher priority, and gives them back to JavaScript to execute.

- After the microtask queue is empty, the setTimeout callback is taken out of the macrotask queue and given back to JavaScript to execute.

In console:

// What soup?

// the data from the api

// hello

Promises

Now you should have a good deal of knowledge about how asynchronous code is handled by JavaScript and the browser environment. So let's talk about promises.

A promise is a JavaScript construct that represents a future unknown value. Conceptually, a promise is just JavaScript promising to return a value. It could be the result from an API call, or it could be an error object from a failed network request. You're guaranteed to get something.

const promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

// Make a network request

if (response.status === 200) {

resolve(response.body)

} else {

const error = { ... }

reject(error)

}

})

promise.then(res => {

console.log(res)

}).catch(err => {

console.log(err)

})

A promise can have the following states:

- fulfilled - action successfully completed

- rejected - action failed

- pending - neither action has been completed

- settled - has been fulfilled or rejected

A promise receives a resolve and a reject function that can be called to trigger one of these states.

One of the big selling points of promises is that we can chain functions that we want to happen on success (resolve) or failure (reject):

- To register a function to run on success we use .then

- To register a function to run on failure we use .catch

// Fetch returns a promise

fetch("https://swapi.dev/api/people/1")

.then((res) => console.log("This function is run when the request succeeds", res)

.catch(err => console.log("This function is run when the request fails", err)

// Chaining multiple functions

fetch("https://swapi.dev/api/people/1")

.then((res) => doSomethingWithResult(res))

.then((finalResult) => console.log(finalResult))

.catch((err => doSomethingWithErr(err))

Perfect. Now let's take a closer look at what this looks like under the hood, using fetch as an example:

const fetch = (url, options) => {

// simplified

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

const xhr = new XMLHttpRequest()

// ... make request

xhr.onload = () => {

const options = {

status: xhr.status,

statusText: xhr.statusText

...

}

resolve(new Response(xhr.response, options))

}

xhr.onerror = () => {

reject(new TypeError("Request failed"))

}

}

fetch("https://swapi.dev/api/people/1")

// Register handleResponse to run when promise resolves

.then(handleResponse)

.catch(handleError)

// conceptually, the promise looks like this now:

// { status: "pending", onsuccess: [handleResponse], onfailure: [handleError] }

const handleResponse = (response) => {

// handleResponse will automatically receive the response, ¨

// because the promise resolves with a value and automatically injects into the function

console.log(response)

}

const handleError = (response) => {

// handleError will automatically receive the error, ¨

// because the promise resolves with a value and automatically injects into the function

console.log(response)

}

// the promise will either resolve or reject causing it to run all of the registered functions in the respective arrays

// injecting the value. Let's inspect the happy path:

// 1. XHR event listener fires

// 2. If the request was successfull, the onload event listener triggers

// 3. The onload fires the resolve(VALUE) function with given value

// 4. Resolve triggers and schedules the functions registered with .then

So we can use promises to do asynchronous work, and to be sure that we can handle any result from those promises. That is the value proposition. If you want to know more about promises you can read more about them here and here.

When we use promises, we chain our functions onto the promise to handle the different scenarios.

This works, but we still need to handle our logic inside callbacks (nested functions) once we get our results back. What if we could use promises but write synchronous looking code? It turns out we can.

Async/Await

Async/Await is a way of writing promises that allows us to write asynchronous code in a synchronous way. Let's have a look.

const getData = async () => {

const response = await fetch("https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/todos/1")

const data = await response.json()

console.log(data)

}

getData()

Nothing has changed under the hood here. We are still using promises to fetch data, but now it looks synchronous, and we no longer have .then and .catch blocks.

Async / Await is actually just syntactic sugar providing a way to create code that is easier to reason about, without changing the underlying dynamic.

Let's take a look at how it works.

Async/Await lets us use generators to pause the execution of a function. When we are using async / await we are not blocking because the function is yielding the control back over to the main program.

Then when the promise resolves we are using the generator to yield control back to the asynchronous function with the value from the resolved promise.

You can read more here for a great overview of generators and asynchronous code.

In effect, we can now write asynchronous code that looks like synchronous code. Which means that it is easier to reason about, and we can use synchronous tools for error handling such as try / catch:

const getData = async () => {

try {

const response = await fetch("https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/todos/1")

const data = await response.json()

console.log(data)

} catch (err) {

console.log(err)

}

}

getData()

Alright. So how do we use it? In order to use async / await we need to prepend the function with async. This does not make it an asynchronous function, it merely allows us to use await inside of it.

Failing to provide the async keyword will result in a syntax error when trying to use await inside a regular function.

const getData = async () => {

console.log("We can use await in this function")

}

Because of this, we can not use async / await on top level code. But async and await are still just syntactic sugar over promises. So we can handle top level cases with promise chaining:

async function getData() {

let response = await fetch('http://apiurl.com');

}

// getData is a promise

getData().then(res => console.log(res)).catch(err => console.log(err);

This exposes another interesting fact about async / await. When defining a function as async, it will always return a promise.

Using async / await can seem like magic at first. But like any magic, it's just sufficiently advanced technology that has evolved over the years. Hopefully now you have a solid grasp of the fundamentals, and can use async / await with confidence.

Conclusion

If you made it here, congrats. You just added a key piece of knowledge about JavaScript and how it works with its environments to your toolbox.

This is definitely a confusing subject, and the lines are not always clear. But now you hopefully have a grasp on how JavaScript works with asynchronous code in the browser, and a stronger grasp over both promises and async / await.

If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy my youtube channel. I currently have a web fundamentals series going where I go through HTTP, building web servers from scratch and more.

There's also a series going on building an entire app with React, if that is your jam. And I plan to add much more content here in the future going in depth on JavaScript topics.

And if you want to say hi or chat about web development, you could always reach out to me on twitter at @foseberg. Thanks for reading!