By Kevin Ghadyani

Breaking tough problems into small pieces.

I wanted to see someone else’s take on software engineering and started binge watching TechLead on YouTube. I spent the next few days coming up with various solutions to an interview question he asked while working at Google.

This Video Got Me Excited

TechLead brought up a question he asked in over 100 interviews at Google. It got me curious to think up a solution in RxJS. This article’s going to go over traditional methods though.

The real goal of his question is to get information from the interviewee. Will they ask the right questions before coding? Is the solution going to fit into the guidelines of the project? He even notes it doesn’t matter at all if you get the right answer. He wants to figure out how you think and if you can even understand the problem.

He talked about a few solutions, one that was recursive (limited by stack size), another that was iterative (limited by memory size). We’ll be looking into both of these and more!

TechLead’s Question

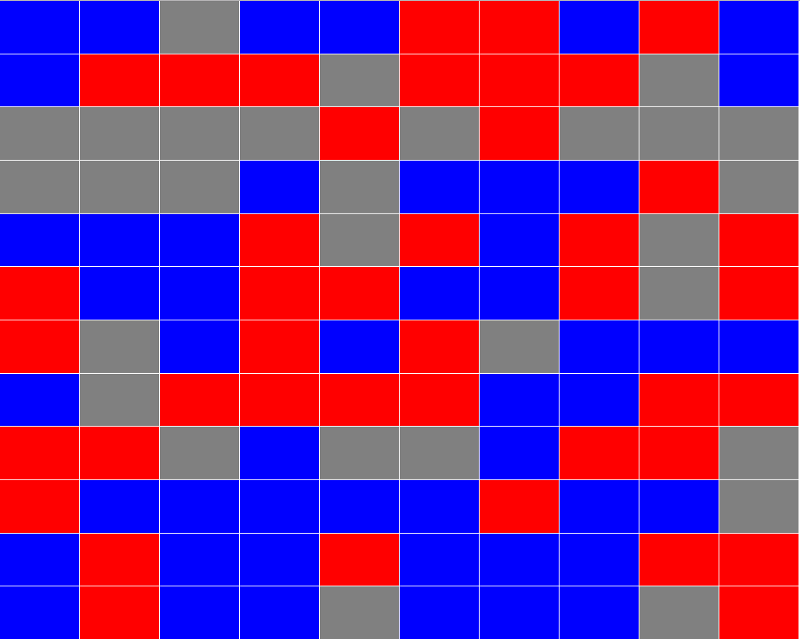

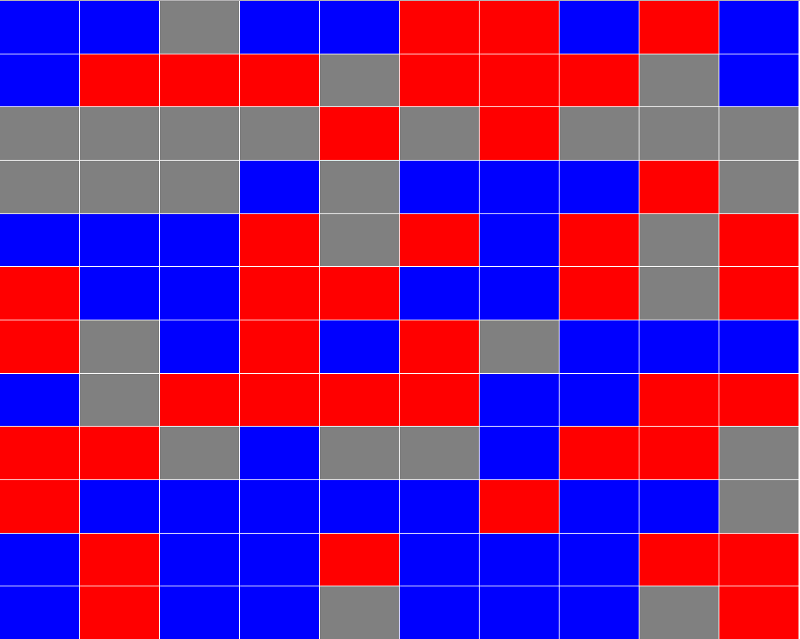

In his question, he asks us to take this grid of items and get the count of the largest contiguous block where all colors are the same.

When I heard his question and saw the picture, I was thinking “oh man, I’ve gotta do some 2D image modeling to figure this out”. Sounds near-impossible to answer during an interview.

But after he explained it more, that’s really not the case. You’re processing the data that’s already been captured, not parsing an image. I realize now, the image is actually a misnomer.

Data Modeling

Before you write any code, you need to define your data model. I can’t stress this enough. Before coding anything this advanced, first figure out what you’re working with and gather business requirements.

In our case, TechLead defined a lot of those requirements for us:

- Concept of a colored square or “node” as we’ll call it.

- There are 10K nodes in our dataset.

- Nodes are organized into columns and rows (2D).

- The number of columns and rows can be uneven.

- Nodes have colors and some way to denote adjacencies.

We can also derive some more information from our data:

- No two nodes will overlap.

- Nodes will never be adjacent to themselves.

- A node will never have duplicate adjacencies.

- Nodes that reside on the sides and corners will be missing one or two adjacencies respectively.

What we don’t know:

- The ratio of rows to columns

- The number of possible colors.

- The chances of having only 1 color.

- The rough distribution of colors.

The higher level you are as a developer, the more of these questions you’ll know to ask. It’s not a matter of experience either. While that helps, it doesn’t make you any better if you can’t pick out the unknowns.

I don’t expect most people to pick out these unknowns. Until I started working the algorithm in my head, I didn’t know them all either. Unknowns take time to figure out. It’s a lot of discussion and back-and-forth with business people to find all the kinks.

Looking at his image, it appears as though the distribution is random. He used only 3 colors and never said anything otherwise, so we will too. We’ll also assume there’s a likelihood all colors will be the same.

Since it could kill our algorithm, I’m going to assume we’re working with a 100x100 grid. That way, we don’t have to deal with the odd cases of 1 row and 10K columns.

In a typical setting, I would ask all these questions within the first few hours of data-discovery. That’s what TechLead really cared about. Are you gonna start by coding a random solution or are you going to figure out the problem?

You’re going to make mistakes in your data model. I know I did when first writing this article, but if you plan ahead, those issues will be a lot easier to manage. I ended up having to only rewrite small portions of my code because of it.

Creating the Data Model

We need to know how data is coming in and in what format we want to process it.

Since we don’t have a system in place for processing the data, we need to come up with a visualization ourselves.

The basic building blocks of our data:

- Color

- ID

- X

- Y

Why do we need an ID? Because we could come across the same item more than once. We want to prevent infinite loops so we need to mark where we’ve been in those cases.

Also, data like this will typically be assigned some sort of ID, hash, or other value. It’s a unique identifier so we have some way to identify that particular node. If we want to know the largest contiguous block, we need to know which nodes are in that block.

Since he shaped out the data in a grid, I’m going to assume we’ll get it back with X and Y values. Using just those properties, I was able to generate some HTML to ensure what we’re generating looks like what he’s given us.

This was done using absolute positioning just like his example:

It even works with a larger dataset:

He’s the code which generates the nodes:

We take our columns and rows, create a 1D array out of the number of items, then generate our nodes off that data.

Instead of a color, I’m using colorId. First, because it’s cleaner to randomize. Second, we’d usually have to look up the color value ourselves.

While he never explicitly stated it, he only used 3 color values. I’m limiting our dataset to 3 colors as well. Just know it could be hundreds of colors and the final algorithms wouldn’t need to change.

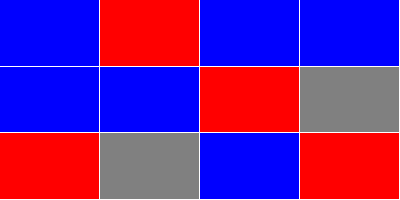

As a simpler example, here’s a 2x2 nodes list:

Data Processing

No matter which method we’re going to use, we want to know the adjacencies for each of these nodes. X and Y values aren’t going to cut it.

So given an X and Y, we need to figure out how to find adjacent X and Y values. It’s pretty simple though. We simply find nodes plus and minus 1 on both X and Y.

I wrote a helper function for that piece of the logic:

The way we’re generating nodes, there’s actually a mathematical way to figure out the IDs of adjacent nodes. Instead, I’m going to assume nodes will come into our system in random order.

I ran all nodes through a second pass to add adjacencies:

I’ve avoided making any unnecessary optimizations in this preprocessor code. It won’t affect our final performance stats and will only help to simplify our algorithms.

I went ahead and changed the colorId into a color. It’s completely unnecessary for our algorithms, but I wanted to make it easier to visualize.

We call getNodeAtLocation for each set of adjacent X and Y values and find our northId, eastId, southId, and westId. We don’t pass on our X and Y values since they’re no longer required.

After getting our cardinal IDs, we convert them to a single adjacentIds array which includes only those that have a value. That way, if we have corners and sides, we don’t have to worry about checking if those IDs are null. It also allows us to loop an array instead of manually noting each cardinal ID in our algorithms.

Here’s another 2x2 example using a new set of nodes run through addAdjacencies:

Preprocessing Optimizations

I wanted to simplify the algorithms for this article greatly, so I added in another optimization pass. This one removes adjacent IDs that don’t match the current node’s color.

After rewriting our addAdjacencies function, this is what we have now:

I slimmed down addAdjacencies while adding more functionality.

By removing nodes that don’t match in color, our algorithm can be 100% sure any IDs in the adjacentIds prop are contiguous nodes.

Lastly, I removed any nodes that don’t have same-color adjacencies. That simplifies our algorithms even more, and we’ve shrunk the total nodes to only those we care about.

The Wrong Way — Recursion

TechLead stated we couldn’t do this algorithm recursively because we’d hit a stack overflow.

While he’s partly correct, there are a few ways to mitigate this problem. Either iterating or using tail recursion. We’ll get to the iterative example, but JavaScript no longer has tail recursion as a native language feature.

While we can still simulate tail recursion in JavaScript, we’re going to keep this simple and create a typical recursive function instead.

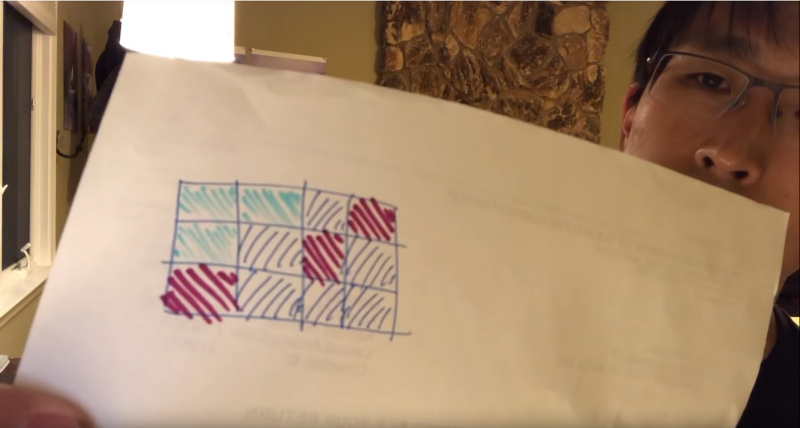

Before we hit the code, we need to figure out our algorithm. For recursion, it makes sense to use a depth-first search. Don’t worry about knowing the computer science term. A coworker said it when I was showing him the different solutions I came up with.

The Algorithm

We’ll start with a node and go as far as we can until we’ve hit an endpoint. Then we’ll come back and take the next branching path until we’ve scanned the entire contiguous block.

That’s part of it. We also have to keep track of where we’ve been and the length of the largest contiguous block.

What I did was divide our function into 2 pieces. One would hold the largest list and previously scanned IDs while looping every node at least once. The other would start at an unscanned root node and do our depth-first traversal.

Here’s what those functions look like:

Insane right? I even debated showing the code because it gets so gnarly.

To slim this down, let’s go step-by-step.

The Recursive Function

getContiguousIds is our recursive function. This gets called once for each node. Each time it returns, you get an updated list of contiguous nodes.

There is only one condition in this function: is our node already in the list? If not, call getContiguousIds again. When it returns, we’ll have an updated list of contiguous nodes which returns to our reducer and used as the state for the next adjacentId.

You might be wondering where we’re adding values to contiguousIds. That happens when we concat the current node onto contiguousIds. Each time we recurse further, we’re making sure to add the current node onto the list of contiguousIds before looping its adjacentIds.

Always adding the current node ensures we don’t infinitely recurse.

The Loop

The second half of this function also goes through each node once.

We have reducer surrounding the recursive function. This one checks if our code’s been scanned. If so, keep looping until we find a node that hasn’t or until we fall out of the loop.

If our node hasn’t been scanned, call getContiguousIds and wait till it’s done. This is synchronous, but it can take some time.

Once it comes back with a list of contiguousIds, check those against the largestContiguousIds list. If larger, store that value.

At the same time, we’re going to add those contiguousIds to our scannedIds list to mark where we’ve been.

It’s pretty simple when you see it all laid out.

Execution

Even with 10K items, it didn’t run into stack overflow issues with 3 randomized colors. If I changed everything to use a single color, I was able to run into a stack overflow. That’s because our recursive function was going through 10K recursions.

Sequential Iteration

Since memory is larger than the function call stack, my next thought was doing the whole thing in a single loop.

We’re going to keep track of a list of node lists. We’ll keep adding to them and linking them together until we fall out of the loop.

This method requires we keep all possible node lists in memory until we’ve completed the loop. In the recursive example, we only kept the largest list in memory.

Another crazy one. Let’s break this down from the top. We’re looping each node once. But now we have to check if our id is in the list of node lists: contiguousIdsList.

If it’s not in any list of contiguousIds, we’ll add it and its adjacentIds. That way, while looping, something else will link up to it.

If our node is in one of the lists, it’s possible it’s in quite a few of them. We want to link all those together, and remove the unlinked ones from the contiguousIdsList.

That’s it.

After we’ve come up with a list of node lists, then we check which one’s the largest, and we’re done.

Execution

Unlike the recursive version, this one does finish when all 10K items are the same color.

Other than that, it’s pretty slow; much slower than I originally expected. I’d forgot to account for looping the list of lists in my performance estimates, and that clearly had an impact on performance.

Random Iteration

I wanted to take the methodology behind the recursive method and apply it iteratively.

I spent the good portion of a night trying to remember how to change the index in the loop dynamically and then I remembered while(true). It’s been so long since I’ve written traditional loops, I’d completely forgotten about it.

Now that I’d had my weapon, I moved in for the attack. As I spent a lot of time trying to speed up the observable versions (more on that later), I decided to go in lazy and old-school-mutate the data.

The goal of this algorithm was to hit each node exactly once and only store the largest contiguous block:

Even though I wrote this like most people probably would, it’s by far the least readable. I can’t even tell you what it’s going without going through it myself first top-to-bottom.

Instead of adding to a list of previously scanned IDs, we’re splicing out values from our remainingNodes array.

Lazy! I wouldn’t ever recommend doing this yourself, but I was at the end of my rope creating these samples and wanted to try something different.

The Breakdown

I broke this out into 3 sections separated by if blocks.

Let’s start with the middle section. We’re checking for queuedIds. If we have some, we do another loop through the queued items to see if they’re in our remainingNodes.

In the third section, it depends on the results of the second section. If we don’t have any queuedIds, and remainingNodesIndex is -1, then we’re done with that node list and we need to start at a new root node. The new root node is always at index 0 because we’re splicing our remainingNodes.

Back at the top of our loop, I could’ve used while(true), but I wanted a way out in case something went wrong. This was helpful while debugging since infinite loops can be a pain to figure out.

After that, we’re splicing out our node. We’re adding it to our list of contiguousIds, and adding the adjacentIds onto the queue.

Execution

This ended up being nearly as fast as the recursive version. It was the fastest of all algorithms when all nodes are the same color.

Data-Specific Optimizations

Grouping Similar Colors

Since we know only blues go with blues, we could’ve grouped similarly colored nodes together for the sequential iteration version.

Splitting it up into 3 smaller arrays lowers our memory footprint and the amount of looping we need to do in our list of lists. Still, that doesn’t solve the situation where all colors are the same so this wouldn’t fix our recursive version.

It also means we could multi-thread the operation, lowering the execution time by nearly a third.

If we execute these sequentially, we just need to run the largest of the three first. If the largest is larger than the other two, you don’t need to check them.

Largest Possible Size

Instead of checking if we have the largest list at certain intervals, we could be checking each iteration.

If the largest set is greater than or equal to half the available nodes (5K or higher), it’s obvious we already have the largest.

Using the random iteration version, we could find the largest list size so far and see how many nodes are remaining. If there are less than the size of the largest, we’ve already got the largest.

Use Recursion

While recursion has its limitations, we can still use it. All we have to do is check the number of remaining nodes. If it’s under the stack limit, we can switch to the faster recursive version. Risky, but it’d definitely improve the execution time as you got further along in your loop.

Use a for Loop

Since we know our max item count, there’ll be a minor benefit from switching the reduce function to a traditional for loop.

For whatever reason, Array.prototype methods are incredibly slow compared to for loops.

Use Tail Recursion

In the same way, I didn’t go over the observable versions in this particular article, I think tail recursion requires an article of its own.

It’s a big topic with a lot to explain, but while it would allow the recursive version to run, it might not end up being faster than the while loop like you’d expect.

RxJS: Maintainability vs Performance

There are ways to rewrite these functions where you’ll have an easier time comprehending and maintaining them. The primary solution I came up with used RxJS in the Redux-Observable style, but without Redux.

That was actually my challenge for the article. I wanted to code the regular ways, then stream the data using RxJS to see how far I could push it.

I made 3 versions in RxJS and took a few liberties to speed up the execution time. Unlike my transducer articles, all three wound up slower even if I increased rows and columns.

I spent my nights that week dreaming up possible solutions and combing over every inch of code. I’d even lie on the ground, close my eyes, and think think think. Each time, I came up with better ideas but kept hitting JavaScript speed limitations.

There’s a whole list of optimizations I could’ve done, but at the cost of code readability. I didn’t want that (still used one anyway).

I finally got one of the observable solutions — now the fastest — running in half the time. That was the best improvement overall.

The only time I could beat out the memory-heavy sequential iteration with observables was when every node is the same color. That was the only time. Technically that beats the recursive one too because it stack overflows in that scenario.

After all that work figuring out how to stream the data with RxJS, I realized it’s way too much for this one article. Expect a future article to go over those code examples in detail.

If you want to see the code early, you can see it on GitHub:

https://github.com/Sawtaytoes/JavaScript-Performance-Interview-Question

Final Stats

In general, the largest contiguous block was anywhere from 30–80 nodes on average.

These are my numbers:

No matter how many times I ran the tests, the relative positions of each method remained the same.

The Redux-Observable Concurrent method suffered when all nodes were the same color. I tried a bunch of things to make it faster, but nothing worked :/.

Game Development

I’ve come across this code twice in my career. It was at a much smaller scale, in Lua, and happened while working on my indie game Pulsen.

In one situation, I was working on a world map. It had a predefined list of nodes, and I processed this list in real-time. This allowed hitting [LEFT], [RIGHT], [UP], and [DOWN] to move you around the world map even if the angle was slightly off.

I also wrote a node generator for an unknown list of items with X and Y values. Sound familiar? I also had to center that grid on the screen. It was a heckuva lot easier to do this in HTML than it was in the game engine though. Although, centering a bunch of absolutely-positioned divs isn’t easy either.

In both of these solutions, the real-time execution time wasn’t a big deal because I did a lot of preprocessing when you loaded up the game.

I want to emphasize that TechLead’s question might be something you come across in your career; maybe, but it’s rare that speed is ever a factor in typical JavaScript applications.

Based on TechLeads other videos, he was using Java at Google. I’m assuming the positions he interviewed cared about execution speed. They probably had a bunch of worker tasks processing huge chunks of data so a solution like this might’ve been necessary.

But then, it could’ve been a job working on HTML and CSS, and he was just trolling the interviewee; who knows!

Conclusion

As you saw with the final stats, the worst-looking code was almost the fastest and accomplished all our requirements. Good luck maintaining that sucker!

From my own experience, I spent longer developing the non-RxJS versions. I think it’s because the faster versions required thinking holistically. Redux-Observable allows you to think in small chunks.

This was a really fun and frustrating problem to solve. It seemed really difficult at first, but after breaking it up into pieces, the pieces all came together :).

More Reads

If you wanna read more on JavaScript performance, check out my other articles:

If you liked what you read, please check out my other articles on similar eye-opening topics: