These days there are plenty of trendy ways to improve your programming skills and knowledge, including:

Taking a free or paid online programming course

Reading a programming book

Picking a personal project and hacking away to learn as you code

Following along with an online tutorial project

Keeping up to date with relevant programming blogs

Each of these methods will appeal to different people, and each one has elements that will definitely make you a better programmer. If you are an intermediate or advanced coder, it is almost certain that you've tried each of these methods at least once.

However, there is another method that the vast majority of developers overlook, which is a shame in my opinion because it has so much to offer. This method is to learn by reading, analyzing, and understanding existing, high-quality codebases!

We are lucky to live in a time where good code is often accessible for free via high-quality, free-and-open-source (FOSS) projects. And it takes less than a minute to clone down copies of these codebases to our local machines from sites like GitHub or BitBucket.

Furthermore, modern version control systems like Git allow us to view the code at any point in its development history. Clearly there is a wealth of information right in front of our noses!

In this article, we will discuss the original version of Git's code in order to highlight how reading existing code can help boost your coding skills.

We will cover why it's worth learning about Git's code, how to access Git's code, and review some related C programming concepts.

We will provide an overview of Git's original codebase structure and learn how Git's core functionalities are implemented in code.

Finally, we will recommend some next steps for curious developers to continue learning from Git's code and other projects.

Why Learn About Git's Code?

Git's codebase is an incredible resource for intermediate developers to further their programming knowledge and skills. Here are 7 reasons why it's worth digging into Git's code:

Git is probably the most popular software dev tool in use today. In short, if you're a developer, you probably use Git. Learning how Git's code works will give you a deeper understanding of an essential tool you work with every day.

Git is interesting! Git is a versatile tool that solves many interesting problems to allow developers to collaborate on code. As a curious human, I thoroughly enjoyed learning more about it.

Git's code is written in the C programming language, which offers a great opportunity for developers to branch out into an important language they may not have used much before.

Git makes use of many important programming concepts, including content-addressable databases, file compression/inflation, hash functions, caching, and a simple data model. Git's code illustrates how these concepts can be implemented in a real project.

Git's code and design are elegant. It is a great example of a functional, minimalist codebase that accomplishes its goal in a clear, effective way.

Git's initial commit is small in size – it is made up of only 10 files, containing less than 1,000 total lines of code. This is very small compared to most other projects and is very manageable to understand in a reasonable amount of time.

The code in Git's initial commit can be compiled and executed successfully. This means you can play with and test the original version of Git's code to see how it works.

Now, let's take a look at how to access the original version of Git's code.

How to check out Git's initial commit?

The official copy of Git's codebase is hosted in this public GitHub repository. However, I created a fork of Git's codebase and added extensive inline comments to the source code, to help developers easily read through it line by line.

Since I worked off of the very first commit in Git's history, I named this project Baby Git. The Baby Git codebase is located in this public BitBucket repository.

I recommend cloning the Baby Git codebase to your local machine by running the following command in your terminal:

git clone https://bitbucket.org/jacobstopak/baby-git.git

If you want to stick with Git's original codebase (without the extensive comments I added), use this command instead:

git clone https://github.com/git/git.git

Browse into the new git directory by running the command cd git. Feel free to poke around the folders and files in here.

You'll quickly notice that in the current version of Git – the version currently checked out in your working directory – that there are a lot of files containing a lot of very long and complicated-looking code.

Clearly this current version of Git is too big for a single developer to realistically get acquainted with in a reasonable amount of time.

Let's simplify things by checking out Git's initial commit, using the command:

git log --reverse

This shows a list of Git's commit log in reverse order, starting from Git's initial commit. Note that the first commit ID in the list is e83c5163316f89bfbde7d9ab23ca2e25604af290.

Check out the contents of this commit into the working directory by running the command:

git checkout e83c5163316f89bfbde7d9ab23ca2e25604af290

This puts Git into a detached head state and places Git's original code files into the working directory.

Now run the ls command to list these files, and note that there are only 10 that actually contain code! (The 11th is just a README). Understanding the code in these files is totally manageable for an intermediate developer!

Note: If you're using my Baby Git repository, you'll want to run the command git checkout master to abandon the detached head and move back to the tip of the master branch. This will enable you to see all the inline comments describing how Git's code works line by line!

Important C Concepts that Will Help You Understand Git's Code

Before diving straight into Git's code, it helps to get a refresher on a few C programming concepts that appear throughout the codebase.

C Header Files

A C header file is a code file ending in the .h extension. Header files are used to store variables, functions, and other C objects that a developer wants to include in multiple .c source code files using the #include "headerFile.h" directive.

If you're familiar with importing files in Python or Java, this is a comparable procedure.

C Function Prototypes (or Function Signatures)

A function prototype or signature tells the C compiler information about a function definition – the function's name, number of argument, types of arguments, and return type – without providing a function body. They help the C compiler identify function properties in situations where the function body appears after the function is called.

Here is an example of a function prototype:

int multiplyNumbers(int a, int b);

C Macros

A macro in C is essentially a rudimentary variable that is processed before code compilation in a C program. Macros are created using the #define directive, such as:

#define TESTMACRO asdf

This creates a macro called TESTMACRO with a value of asdf. Wherever the placeholder TESTMACRO is used in the code, it will be replaced by the preprocessor (before code compilation) with the value asdf.

Macros are commonly used in a few ways:

As a true/false switch by checking whether a macro is defined

To store a simple integer or string value to be replaced in the code in multiple locations

To store a simple (usually one-line) code snippet to be replaced in the code in multiple locations

Macros are convenient tools since they enable developers to update a single line of code which influences the behavior of the code in multiple locations.

C Structs

A struct in C is a grouped set of properties that are related to a single object.

You are probably familiar with Classes in languages such as Java and Python. A struct is a predecessor to a class – it can be thought of as a primitive class with no methods.

struct person {

int person_id;

char *first_name;

char *last_name;

};

This struct represents a person, by grouping together an ID field, along with the person's first and last names. A variable can be instantiated and initialized from this struct as follows:

struct person jacob = { 1, "Jacob", "Stopak" };

Struct properties can be retrieved using the dot operator:

jacob.person_id

jacob.first_name

jacob.last_name

C Pointers

A pointer is a memory address of a variable – it is the memory address at which the value of that variable is stored.

A pointer to an existing variable can be obtained by using the & symbol, and stored in a pointer variable declared with the * symbol:

int age = 21;

int* age_pointer = &age;

This snippet defines the variable age and assigns it a value of 21. Then it defines a pointer to an integer called age_pointer, and uses the & to obtain the memory address that the value of the age variable is stored at.

Pointers can be dereferenced (i.e. obtain the value stored at the memory address), using the * as well.

int new_age = *age_pointer + 10;

Continuing from our previous example, we use the *age_pointer syntax to fetch the value stored in the pointer (21), and add 10 to it. So the new_age variable would contain a value of 31.

Now that our short segue into C programming is completed, let's get back to Git's code.

Overview of Git's Codebase Structure

There are ten relevant code files that make up Git's initial commit. We'll start by briefly discussing these two:

Makefile

cache.h

We'll discuss Makefile and cache.h first because they are a bit special.

Makefile is a build file that contains a set of commands used to build the other source code files into executables.

When you run the command make all from the command line, the Makefile will compile the source code files and spit out the relevant executables for Git's commands. If you're interested, I wrote an in-depth guide on Git's makefile.

Note: If you actually want to compile Git's code locally, which I recommend you do, you'll need to use my Baby Git version of the code mentioned above. The reason is that I made some tweaks to allow Git's original code to compile on modern operating systems.

Next up is the cache.h file, which is Baby Git's only header file. As mentioned above, the header file defines many of the function signatures, structs, macros, and other settings that are used in the .c source code files. If you're curious, I wrote an in-depth guide on Git's header file.

The remaining eight code files are all .c source code files:

init-db.cupdate-cache.cread-cache.cwrite-tree.ccommit-tree.cread-tree.ccat-file.cshow-diff.c

Each file (except read-cache.c) is named after the Git command that it contains the code for – some probably look familiar to you. For example, the init-db.c file contains the code for the init-db command used to initialize a new Git repository. As you probably guessed, this was the precursor to the git init command.

In fact, each of these .c files (except read-cache.c) contains the code for one of the original eight Git commands. The build process compiles each of these files and creates an executable file (with matching name) for each one. Once these executables are added to the filesystem path, they can be executed similarly to any modern Git command.

So after compiling the code using the make all command, the following executables are produced:

init-db: Initializes a new Git repository. Equivalent togit init.update-cache: Add a file to the staging index. Equivalent togit add.write-tree: Creates a tree object in the Git repository from the current index contents.commit-tree: Creates a new commit object in the Git repository. Equivalent togit commit.read-tree: Print out the contents of a tree from the Git repository.cat-file: Retrieve the the contents of an object from the Git repository, and store it in a temporary file in the current directory. Equivalent togit show.show-diff: Show the differences between files staged in the index and the current versions of those files as they exist in the filesystem. Equivalent togit diff.

These commands are executed individually in sequence, similar to how modern Git commands are executed as a part of standard development workflows.

The one file we haven't discussed yet is read-cache.c. This file contains a set of helper functions that the other .c source code files use to retrieve information from the Git repository.

Now that we've touched on each of the important files in Git's initial commit, let's discuss some of the core programming concepts that allow Git to function.

Implementation of Git's Core Concepts

In this section, we'll discuss the following programming concepts that Git uses to work its magic, as well as how they were implemented in Git's original code:

File compression

Hash function

Objects

Current directory cache (staging area)

Content addressable database (object database)

File Compression

File compression, also know as deflation, is used for storage and performance efficiency in Git. This reduces the size of the files that Git stores on disk and increases the speed of data retrieval when Git needs to transfer these files across a network.

This is important since Git's local and network operations need to be as fast as possible. As a part of the data retrieval process, Git decompresses, or inflates, the files to obtain their content.

Source: https://initialcommit.com/blog/Learn-Git-Guidebook-For-Developers-Chapter-2

File deflation and inflation were implemented in Git's original code using the popular zlib.h C library. This library contains functions, structures, and properties for compressing and decompressing content. Specifically, Zlib defines a z_stream struct that is used to hold the content that is to be deflated or inflated.

The following zlib functions are used to initialize a stream for deflation or inflation, respectively:

/*

* Initializes the internal `z_stream` state

* for compression at `level`, which indicates

* scale of speed versuss compression on a

* scale from 0-9. Sourced from <zlib.h>.

*/

deflateInit(z_stream, level);

/*

* Initializes the internal `z_stream` state for

* decompression. Sourced from <zlib.h>.

*/

inflateInit(z_stream);

The following zlib functions are used to perform the actual deflation and inflation operations:

/*

* Compresses as much data as possible and stops

* when the input buffer becomes empty or the

* output buffer becomes full. Sourced from <zlib.h>.

*/

deflate(z_stream, flush);

/*

* Decompresses as much data as possible and stops

* when the input buffer becomes empty or the

* output buffer becomes full. Sourced from <zlib.h>.

*/

inflate(z_stream, flush);

The actual deflation/inflation process is a bit more complex than this and involves setting several parameters of the compression stream, but we won't go into more detail here.

Next, we'll discuss the concept of hash functions and how they are implemented in Git's original code.

Hash Functions

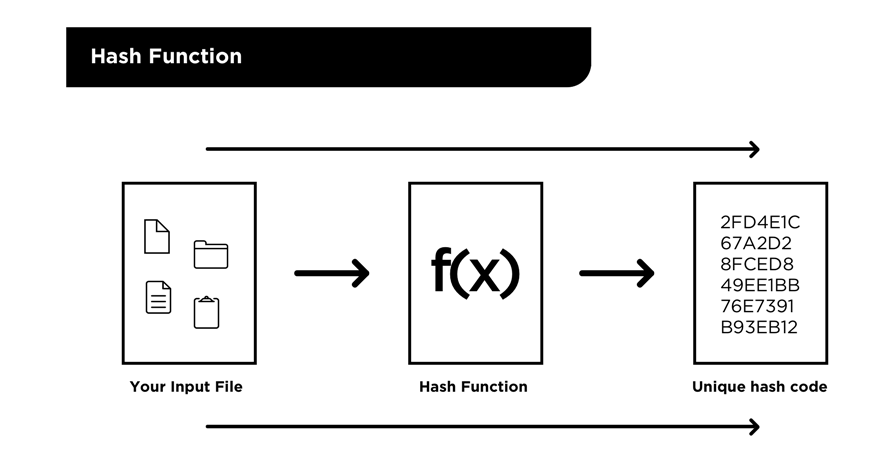

A hash function is a function that can easily transform an input into a unique output, but makes it very difficult or impossible to reverse that operation. In other words, it is a one-way function. It is not possible with today's technology to use the output of a hash function to deduce the input that was used to generate that output.

Git uses a hash function – specifically the SHA-1 hash function – to generate unique identifiers for the files we tell Git to track.

As developers, we make changes to the code files in the codebase we are working on using a text editor, and at some point we tell Git to track those changes. At this point, Git uses those file changes as inputs for the hash function.

The output to the hash function is called a hash*.* The hash is a hexadecimal value 40 characters in length, such as 47a013e660d408619d894b20806b1d5086aab03b.

Source: https://initialcommit.com/blog/Learn-Git-Guidebook-For-Developers-Chapter-2

Git uses these hashes for various purposes that we will see in the following sections.

Objects

Git uses a simple data model – a structured set of related objects – to implement its functionality. These objects are the nuggets of information that enable Git to track changes to the files of a codebase. The three types of objects that Git uses are:

Blob

Tree

Commit

Let's discuss each one in turn.

Blob

A blob is short for a Binary Large OBject. When Git is told to track a file using the update-cache <filename.ext> command, (the predecessor to git add), Git creates a new blob using the compressed contents of that file.

Git takes the content of the file, compresses it using the zlib functions we described above, and uses this compressed content as input to the SHA-1 hash function. This creates a 40 character hash that Git uses to identify the blob in question.

Finally, Git saves the blob as a binary file in a special folder called the object database (more on this in a minute). The name of the blob file is the generated hash, and the contents of the blob file are the compressed file contents that were added using update-cache.

Tree

Tree objects are used to link together multiple blobs that are added to Git at once. They are also used to correlate blobs with file names (and other file metadata like permissions), since blobs don't provide any information besides the hash and compressed binary file content.

For example, if two changed files are added using the update-cache command, a tree will be created containing the hashes of those files, along with the file name that each of those blobs corresponds to.

What Git does next is very interesting, so pay attention. Git uses the content of the tree itself as input to the SHA-1 hash function, which generates a 40 character hash. This hash is used to identify the tree object, and Git saves this in the same special folder that blobs are saved in – the object database we'll touch on shortly.

Commit

You're probably more familiar with commit objects than with blobs and trees. A commit represents a set of file changes saved by Git, along with descriptive information about the change such as a commit message, the author's name, and the timestamp of the commit.

In Git's original code, a commit object is the result of running the commit-tree <tree-hash> command. The resulting commit object includes the specified tree object (which remember, represents a collection of file changes via one or more blobs mapped to their file names), and the descriptive information mentioned in the previous paragraph.

Like blobs and trees, Git identifies the commit by hashing its content using the SHA-1 hash function, and saving it in the object database. Importantly, each commit object also contains the hash of its parent commit. In this way, the commits form a chain that Git can use to represent the history of a project.

Current Directory Cache (Staging Area)

You probably know Git's staging area as the place your changed files go after using the git add command, patiently waiting to be committed using git commit. But what exactly is the staging area?

In Git's original version, the staging area is called the current directory cache. The current directory cache is just a binary file stored in the repository at the path .dircache/index.

As mentioned in the previous section, after changed files are added to Git using the update-cache (git add) command, Git calculates the blob and tree objects associated with those changes. The generated tree object associated with the staged files is added to the index file.

It is called a cache because it is just a temporary storage location for the staged changes to reside before being committed. When the user makes a commit by running the commit-tree command, the tree from the current directory cache can be supplied. It also includes other commit information like the commit message for Git to create a new commit object with.

At that point the index file is simply removed to make room for new changes to be staged.

Content Addressable Database (Object Database)

The object database is Git's primary storage location. This is where all the objects we discussed above – blobs, trees, and commits – are stored. In Git's original version, the object database is simply a directory at the path .dircache/objects/.

When Git creates objects through operations such as update-cache, write-tree, and commit-tree, (the predecessors of git add and git commit), these objects are compressed, hashed, and stored in the object database.

The name of each object is the hash of its content, hence why the object database is also called a content addressable database*.* Each piece of content (blob, tree, or commit) is stored and retrieved based on an identifier generated from the content itself.

The modern version of Git works very much the same way. The difference is that storage formats have been optimized to use more efficient methods (especially related to data transfer over networks), but the basic principles are the same.

Summary

In this article, we discussed the original version of Git's code in order to highlight how reading existing code can help boost your coding skills.

We covered the reasons Git is a great project to learn from in this way, how to access Git's code, and reviewed some related C programming concepts. Finally, we provided an overview of Git's original codebase structure and dove into some concepts that Git's code relies on.

Next Steps

If you're interested in learning more about Git's code, we wrote a guidebook you can check out here. This book dives into Git's original C code in detail and directly explains how the code works.

I encourage any and all developers to explore the open-source community to try and find quality projects that interest you. Those projects will have codebases that you can clone down in a matter of minutes.

Take some time to poke around the code, and you might learn something you never expected to find.