by Justin Lynn Reid

Coding from a Meteorologist’s Perspective

Aside from researchers and TV weather people, few people are versed in the technical side of meteorology and atmospheric science.

An eclectic field, atmospheric science combines aspects of mathematics, physics, technical writing, academic research, and mass communication into a field with a unique perspective.

I’ve done work with many of these parts of atmospheric science. What I specialize in now is a bit different then what most meteorologists do with their training.

Instead of focusing on the traditional paths of operational forecasting, TV, or governmental research, I am instead what is known as a meteorological programmer: one part meteorologist, one part software developer.

To quoting one of my former coworkers, meteorology is the “first Big Data problem” where many precursors to the new field of data science exist. Earth observing networks (such as satellites, surface weather stations, weather balloons, and Doppler Weather Radar) are essentially a lower resolution Internet of Things that run 24 hours a day. From those networks several physics models (called Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) Models) are run on supercomputers by either government agencies or private firms that produce a set of best guesses at future atmospheric conditions that forecasters interpret and analyze. It’s these things behind the scenes that produce the weather forecasts you get online or via a local media outlet.

You may be asking, how does all of this relate to something like Free Code Camp, JavaScript or web development? I will highlight some ways that I think the subject directly lends itself to the software development process, and even helps achieve a greater understanding of it.

The Scientific Method and the “Ms. Frizzle Principle”

In atmospheric science, as in other STEM fields, new discoveries or insights are made via experimentation, testing and peer review. Even after being involved with the meteorology industry for many years professionally, I still call this process “the Ms. Frizzle Principle.”

In one episode of The Magic School Bus where Ms. Frizzle and her students were on a field trip exploring an undersea volcano, one of the characters kept citing research already written as her main source of understanding. During the trip, the student loses her books, thereby losing access to the “research” that she keeps citing. In the process of this, she has to learn to draw conclusions based off of her own observations. At the end of the show, the student’s conclusions were ultimately proven right, as she reasoned that the undersea volcano would erupt and form a new island.

If there is anything consistent in the programming work that I’ve done, it’s that I follow this kind of process for each project or task that I complete. Though I do have access to “research” in the forms of documentation, forum posts, and collaboration; there is no one to tell me how to put all the pieces together to create the application that I have to create.

In order to write an application properly I have to break a big problem into a series of smaller problems. And for each of those smaller problems I have to try and find connections between ideas in order to formulate a possible solution.

This is a hypothesis and in programming I can literally write my best guess as lines of code. Then I test those lines of code for that given small problem and see if they have the behavior that should be correct. If the code works then I move on to the next small problem, if not I try to learn why the code failed. And then use that information to make another attempt at solving the small problem.

When you solve all the small problems the application is done. This is why when I heard of Test-Driven Development and frameworks like Jasmine, I found that looking at code in that way was natural for me personally. It was just placed into a formal way of doing things.

If I could give you just two pieces of advice about programming, they would be:

- never tackle a big problem as a whole

- never let a lack of knowledge intimidate you, as each new project is a journey into the unknown, and failure always accompanies the unknown.

Meteorology Domain Technologies and the Web Are Very Close Relatives

Other than the scientific method, meteorology has plenty of domain-specific technologies that make the transition to web development not that difficult.

Besides being exposed to the web such as APIs or via web apps that are made to use meteorological data, many of the underlying concepts of atmospheric science computing directly translate over.

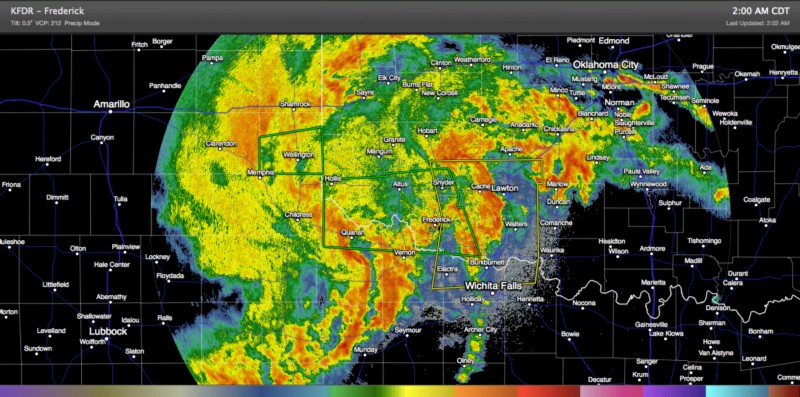

For example, things such as the radar imagery you see on TV are data visualizations, a simplified form of a large set of observations/data that can be interpreted effectively.

In the case of radar and satellite, each observation is a pixel gathered via remote sensing and instead of having pixel values being in a table. The data are rendered in a more useful form.

In web development, data are at the core of how applications behave and appear, as well as the content they have.

Instead of manipulating data in a common meteorology setting (say finding average or maximum temperature), on the web the same concepts are used in a much more general way, such as with D3.js.

Even beyond visualization, common meteorology technologies have more web industry-standard analogues, such as with Unidata LDM and Node.js. Meteorology is inevitable tied to both programming and the web, and both are essential parts of being an atmospheric scientist and a technical professional.

In conclusion, this is how I’ve come to see programming from my personal viewpoint. Each person’s reason for programming is different. I hope this will give some you perspective on how it can be applied to scientific fields.