By Osman (Ozzie) Ahmed Osman

Often, at work, you might come across someone who is “not doing their job”. It can be a peer, a report, or even your own manager. If it’s a report, we’ll often refer to this as a “performance problem”. As a manager of managers, I see examples of this all the time with my peers and colleagues.

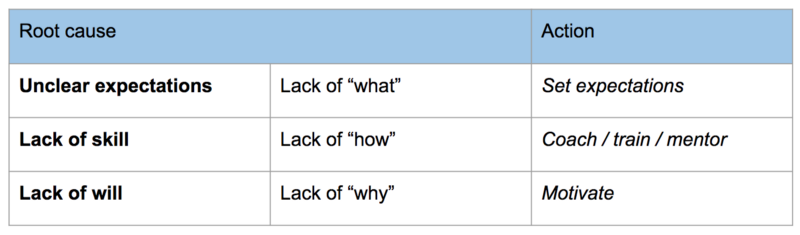

It’s important that you accurately diagnose the problem before trying to fix it. Google has “open-sourced” its manager training slides, and they have a great framework for diagnosis. In their framework, performance problems tend to be caused by:

- Unclear expectations: Your colleague does not know what is expected of them. Maybe their manager (you?) hasn’t set expectations for them clearly, or a team-mate has not clarified that they are blocked on their work or harmed by their quality of work.

- Lack of skill: Your colleague does not know how to perform the tasks expected of them.

- Lack of will: Your colleague is not motivated or interested in doing those tasks (they lack understanding or agreement of why they should be doing those tasks).

Andy Grove has a similar framework in his High Output Management book:

“When a person is not doing his job, there can only be two reasons for it. The person either can’t do it or won’t do it; he is either not capable or not motivated.”

— Andy Grove

Have you ever tried to improve one of these situations and made it worse? I have. When I look back, many times it’s because I applied what I thought was the right solution, but to the wrong problem.

For instance, have you tried to motivate someone to do something that they don’t really know how to do, only causing them (and you) further frustration? On the flip side, have you tried to train someone to do a task they already know how to do, but just have no interest in doing — belittling them and further undermining their motivation?

So… then it’s pretty easy, right? Let’s say one of your reports, John, is not getting his tasks done when you expect him to. Just use this framework, diagnose the problem, and then work on addressing it.

Unfortunately, it’s not so straightforward. The model is simplistic. Our brains tend to work against us in these situations through what are known as “cognitive biases” that tend to simplify situations and misattribute behavior.

Cognitive Biases — How our brains tend to (incorrectly) simplify things

Our brains have evolved to constantly creating simplifications of the world around us. In social situations, we have evolved to quickly label those around us as “good” or “bad”, along two dimensions: competency and motivations.

People are competent or incompetent. They are friends or foes. They can be any combination of that: competent friends (collaborators or leaders), incompetent friends (those we can help), competent foes (rivals, enemies), and so on. (A lot of times, we view ourselves positively on those two dimensions — a phenomenon that has been called “beneffectance”: beneficial and effective.)

Do those two dimensions sound familiar? Competency = skill. Motivations = will. Lack-of-will vs. lack-of-skill is basically a workplace version of that simplification.

The “friend or foe” instinct tends to kick in faster, and from an evolutionary perspective, that makes sense. When our ancestors encountered each other, they had to quickly make that assessment for “fight or flight”, so we tend to be faster and less accurate at making that assessment. We take a little longer to judge competency of others in our tribe or group based on whom we interact with more closely/frequently.

Your brain is constantly simplifying, but you have to prevent your brain from jumping to these conclusions — because we’re often wrong. There’s a few psychological phenomena you can use to fight your own cognitive biases.

The first is the fundamental attribution error. In short, we tend to attribute the behavior of others to their internal characteristics, instead of their circumstances. John is lazy instead of John is unable to do a task because he is busy with other things.

Compounding the fundamental attribution error is confirmation bias. Now that our brain has already created an incorrect attribution, we tend to seek out evidence to support that hypothesis. And, often, if you combine the fundamental attribution error and confirmation bias, you end up with some major horn and halo effects. Since now, John is lazy, we start to find “evidence” of that all over the place, and ignore any evidence to the contrary.

Let’s throw one last cognitive bias into the mix: self-serving bias. As a person’s manager (or even peer), in difficult and ambiguous situations, we’re much more likely to simplify and mis-attribute problems in a way that removes any blame from us. Putting blame on someone’s inherit characteristics (laziness, lack of ability) is easier than admitting that maybe, as managers, we’ve failed to motivate or coach that person.

Check out these two resources to read more.

For example, a split brain subject’s left eye received a command to stand. The person stood, but when asked why she stood up, she responded, using the language center of the left hemisphere, that she wanted a soda.

Reality is much more complicated

So our brains are constantly working against us — simplifying, misattributing, and confabulating. Basically going rogue. On the other hand, in reality, people tend to be much, much more complicated than we think. In fact, the three “reasons” (lack of will, lack of skill, and unclear expectations) tend to bleed into each other in ways that are nuanced and difficult to disentangle.

Let’s take that laziness example again. Someone on your team isn’t doing something that they should clearly know how to do. Sometimes, a “lack of will” problem might have nothing to do with incentives at all, and might be more related to other psychological factors. There’s an excellent piece about procrastination and “laziness” by E Price:

If you look at a person’s action (or inaction) and see only laziness, you are missing key details. There is always an explanation. There are always barriers.

More specifically…

When a person fails to begin a project that they care about, it’s typically due to either a) anxiety about their attempts not being “good enough” or b) confusion about what the first steps of the task are. Not laziness. In fact, procrastination is more likely when the task is meaningful and the individual cares about doing it well.

The first reason, if you boil it down, is actually not a lack of will problem at all. Rather, it’s a perceived lack of skill. Note that it doesn’t really matter whether you think they have the skill to do their task or not. In this case, it’s about their perceived lack of skill/ability. You might have no idea what’s going on in their mind — insecurities, imposter syndrome, depression, past failures. In other words, perceived lack of skill leads to lack of will.

Trying to motivate a person to do a task that they’re procrastinating on due to anxiety is likely to have the opposite effect — it makes the task more meaningful, and increases anxiety.

The second reason, confusion about first steps, is equally as murky. In this case, they lack clarity on how to get started. The ability to start a task is a very different skill than the ability to execute it. If often involves breaking a larger task down into smaller tasks. I might know how to do each of those individual tasks, but I might not actually know how to break the larger task itself down.

This is especially true in software engineering, where the skill to think about an entire system or group of changes is very different than the skill of making smaller, more incremental changes. The former is known as “architecture”, and many companies have very senior roles for people who are purely “architects”.

Some advice

So, what are we to do?

Let’s take that laziness example one more time. John isn’t starting or delivering his tasks on time. He seems to get distracted by other things, some of which might not even be work-related. In fact, he doesn’t seem to want to do any work at all.

First, look at the history, but don’t let cognitive biases trap you. Has John always been like this, or did something change? Surely he was hired or moved to the team with an expectation that he could perform those tasks.

Has this behavior been triggered before? If so, when? Was it related to the nature/difficulty of the tasks? Maybe those tasks are tedious and not challenging. Or maybe they’re too challenging, and trigger a “procrastination” mechanism. Maybe there’s something going on in his personal life. Or maybe he’s unhappy with someone else on his team… or with you!

So on one hand, you need to look at history and patterns to diagnose the situation. However, if you’ve already colored John as being lazy and unmotivated, you will view the history and patterns through that lens, without digging in deep. So beware of those cognitive biases, and seek out evidence to the contrary.

Trust and open communication can also go a long way. Hopefully you’ve invested in relationships with your colleagues, and so can have an open conversation about these issues.

I usually start by asking how they feel about how their work is going, and making it clear I’m trying to help (which you can’t fake, you have to actually want to help). Ask questions with an open mind.

Are you satisfied with how things are going?

Do you think other stakeholders are satisfied?

Why do you think this is happening?

How do you feel?

When, in the past, have you felt this way before?

There are hard, uncomfortable questions. But if you have a good relationship and positive intentions, you can work through them to uncover (and fix) the root cause.

In summary, a few tips:

- Familiarize yourself with the various cognitive biases. Understand the traps you, and others around you, might fall into. Question your own judgment, constantly. The biggest enemy of good performance management is a manager’s tendency to slip into cognitive bias.

- Establish trust and openness with your peers and reports. Understanding someone is infinitely harder if they don’t trust you and if you can’t communicate about problems when they arise. Be empathetic and compassionate.

- Understand motivational theory, especially intrinsic motivation. There’s a lot of literature on that subject, but one of my favorites is Daniel Pink’s Drive.