It’s 2019, and ransomware has become a thing.

Systems that interact with the public, like companies, educational institutions, and public services, are most susceptible. While delivery methods for ransomware vary from the physical realm to communication via social sites and email, all methods only require one person to make one mistake in order for ransomware to proliferate.

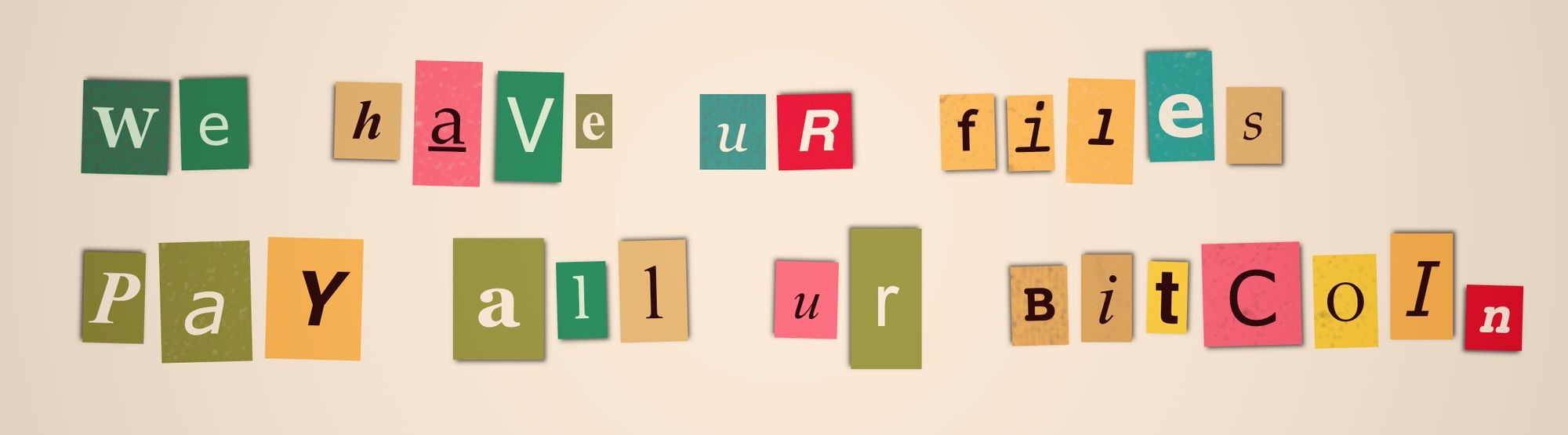

Ransomware, as you may have heard, is a malicious program that encrypts your files, rendering them unreadable and useless to you. It can include instructions for paying a ransom, usually by sending cryptocurrency, in order to obtain the decryption key.

Successful ransomware attacks typically exploit vital, time-sensitive systems. Victims like public services and medical facilities are more likely to have poor or zero recovery processes, leaving governments or insurance providers to reward attackers with ransom payments.

Individuals, especially less-than-tech-savvy ones, are no less at risk. Ransomware can occlude personal documents and family photos that may only exist on one machine.

Thankfully, a fairly low-tech solution exists for rendering ransomware inept: back up your data!

You could achieve this with a straightforward system like plugging in an external hard drive and dragging files over once a day, but this method has a few hurdles. Manually transferring files may be slow or incomplete, and besides, you’ll first have to remember to do it.

Instead, use cron

In my constant pursuit of automating all the things, there’s one tool I often return to for its simplicity and reliability: cron. Cron does one thing, and does it well: it runs commands on a schedule.

I first used it a few months shy of three years ago (Have I really been blogging that long?!) to create custom desktop notifications on Linux. Using the crontab configuration file, which you can edit by running crontab -e, you can specify a schedule for running any commands you like. Here’s what the scheduling syntax looks like, from the Wikipedia cron page:

# ┌───────────── minute (0 - 59)

# │ ┌───────────── hour (0 - 23)

# │ │ ┌───────────── day of the month (1 - 31)

# │ │ │ ┌───────────── month (1 - 12)

# │ │ │ │ ┌───────────── day of the week (0 - 6)

# │ │ │ │ │

# │ │ │ │ │

# │ │ │ │ │

# * * * * * command to execute

For example, a cron job that runs every day at 00:00 would look like:

0 0 * * *

To run a job every twelve hours, the syntax is:

0 */12 * * *

This great tool can help you wrap your head around the cron scheduling syntax.

What’s a scheduler have to do with backing up? By itself, not much. The simple beauty of cron is that it runs commands - any shell commands, and any scripts that you’d normally run on the command line. As you may have gleaned from my other posts, I’m of the strong opinion that you can do just about anything on the command line, including backing up your files. Options for storage in this area are plentiful, from near-to-free local and cloud options, as well as paid managed services too numerous to list. For CLI tooling, we have utilitarian classics like rsync, and CLI tools for specific cloud providers like AWS.

Backing up with rsync

The rsync utility is a classic choice, and can back up your files to an external hard drive or remote server while making intelligent determinations about which files to update. It uses file size and modification times to recognize file changes, and then only transfers changed files, saving time and bandwidth.

The rsync syntax can be a little nuanced; for example, a trailing forward slash will copy just the contents of the directory, instead of the directory itself. I found examples to be helpful in understanding the usage and syntax.

Here’s one for backing up a local directory to a local destination, such as an external hard drive:

rsync -a /home/user/directory /media/user/destination

The first argument is the source, and the second is the destination. Reversing these in the above example would copy files from the mounted drive to the local home directory.

The a flag for archive mode is one of rsync’s superpowers. Equivalent to flags -rlptgoD, it:

- Syncs files recursively through directories (

r); - Preserves symlinks (

l), permissions (p), modification times (t), groups (g), and owner (o); and - Copies device and special files (

D).

Here’s another example, this time for backing up the contents of a local directory to a directory on a remote server using SSH:

rsync -avze ssh /home/user/directory/ user@remote.host.net:home/user/directory

The v flag turns on verbose output, which is helpful if you like realtime feedback on which files are being transferred. During large transfers, however, it can tend to slow things down. The z flag can help with that, as it indicates that files should be compressed during transfer.

The e flag, followed by ssh, tells rsync to use SSH according to the destination instructions provided in the final argument.

Backing up with AWS CLI

Amazon Web Services offers a command line interface tool for doing just about everything with your AWS set up, including a straightforward s3 sync command for recursively copying new and updated files to your S3 storage buckets. As a storage method for back up data, S3 is a stable and inexpensive choice.

The syntax for interacting with directories is fairly straightforward, and you can directly indicate your S3 bucket as an S3Uri argument in the form of s3://mybucket/mykey. To back up a local directory to your S3 bucket, the command is:

aws s3 sync /home/user/directory s3://mybucket

Similar to rsync, reversing the source and destination would download files from the S3 bucket.

The sync command is intuitive by default. It will guess the mime type of uploaded files, as well as include files discovered by following symlinks. A variety of options exist to control these and other defaults, even including flags to specify the server-side encryption to be used.

Setting up your cronjob back up

You can edit your machine’s cron file by running:

crontab -e

Intuitive as it may be, it’s worth mentioning that your back up commands will only run when your computer is turned on and the cron daemon is running. With this in mind, choose a schedule for your cronjob that aligns with times when your machine is powered on, and maybe not overloaded with other work.

To back up to an S3 bucket every day at 8AM, for example, you’d put a line in your crontab that looks like:

0 8 * * * aws s3 sync /home/user/directory s3://mybucket

If you’re curious whether your cron job is currently running, find the PID of cron with:

pstree -ap | grep cron

Then run pstree -ap <PID>.

This rabbit hole goes deeper; a quick search can reveal different ways of organizing and scheduling cronjobs, or help you find different utilities to run cronjobs when your computer is asleep. To protect against the possibility of ransomware-affected files being transferred to your back up, incrementally separated archives are a good idea. In essence, however, this basic set up is all you really need to create a reliable, automatic back up system.

Don’t feed the trolls

Humans are fallible; that’s why cyberattacks work. The success of a ransomware attack depends on the victim having no choice but to pay up in order to return to business as usual.

A highly accessible recent back up undermines attackers who depend on us being unprepared. By blowing away a system and restoring from yesterday’s back up, we may lose a day of progress; ransomers, however, gain nothing at all.

For further resources on ransomware defense for users and organizations, check out CISA’s advice on ransomware.