By Reza Lavarian

It's a bit tricky to explain what exactly a file system is in just one sentence.

That's why I decided to write an article about it. This post is meant to be a high-level overview of file systems. But I'll sneak into the lower-level concepts as well, as long as it doesn't get boring. :)

What is a file system?

Let's start with a simple definition:

A file system defines how files are named, stored, and retrieved from a storage device.

Every time you open a file on your computer or smart device, your operating system uses its file system internally to load it from the storage device.

Or when you copy, edit, or delete a file, the file system handles it under the hood.

Whenever you download a file or access a web page over the Internet, a file system is involved too.

For instance, if you access a page on freeCodeCamp, your browser sends an HTTP request to freeCodeCamp's server to fetch the page. If the requested resource is a file, it's fetched from a file system.

When people talk about file systems, they might refer to different aspects of a file system depending on the context - that's where things start to seem knotty.

And you might end up asking yourself, WHAT IS A FILE SYSTEM ANYWAY? 🤯

This guide helps you understand file systems in many contexts. I'll cover partitioning and booting too!

To keep this guide manageable, I'll concentrate on Unix-like environments when explaining the lower-level concepts or console commands.

However, these concepts remain relevant to other environments and file systems.

Why do we need a file system in the first place, you may ask?

Well, without a file system, the storage device would contain a big chunk of data stored back to back, and the operating system wouldn't be able to tell them apart.

The term file system takes its name from the old paper-based data management systems, where we kept documents as files and put them into directories.

Imagine a room with piles of papers scattered all over the place.

A storage device without a file system would be in the same situation - and it would be a useless electronic device.

However, a file system changes everything:

A file system isn't just a bookkeeping feature, though.

Space management, metadata, data encryption, file access control, and data integrity are the responsibilities of the file system too.

Everything begins with partitioning

Storage devices must be partitioned and formatted before the first use.

But what is partitioning?

Partitioning is splitting a storage device into several logical regions, so they can be managed separately as if they are separate storage devices.

We usually do partitioning by a disk management tool provided by operating systems, or as a command-line tool provided by the system's firmware (I'll explain what firmware is).

A storage device should have at least one partition or more if needed.

Why should we split the storage devices into multiple partitions anyways?

The reason is that we don't want to manage the whole storage space as a single unit and for a single purpose.

It's just like how we partition our workspace, to separate (and isolate) meeting rooms, conference rooms, and various teams.

For example, a basic Linux installation has three partitions: one partition dedicated to the operating system, one for the users' files, and an optional swap partition.

A swap partition works as the RAM extension when RAM runs out of space.

For instance, the OS might move a chunk of data (temporarily) from RAM to the swap partition to free up some space on the RAM.

Operating systems continuously use various memory management techniques to ensure every process has enough memory space to run.

File systems on Windows and Mac have a similar layout, but they don't use a dedicated swap partition; Instead, they manage to swap within the partition on which you've installed your operating system.

On a computer with multiple partitions, you can install several operating systems, and every time choose a different operating system to boot up your system with.

The recovery and diagnostic utilities reside in dedicated partitions too.

For instance, to boot up a MacBook in recovery mode, you need to hold Command + R as soon as you restart (or turn on) your MacBook. By doing so, you instruct the system's firmware to boot up with a partition that contains the recovery program.

Partitioning isn't just a way of installing multiple operating systems and tools, though; It also helps us keep critical system files apart from ordinary ones.

So no matter how many games you install on your computer, it won't have any effect on the operating system's performance - since they reside in different partitions.

Back to the office example, having a call center and a tech team in a common area would harm both teams' productivity because each team has its own requirements to be efficient.

For instance, the tech team would appreciate a quieter area.

Some operating systems, like Windows, assign a drive letter (A, B, C, or D) to the partitions. For instance, the primary partition on Windows (on which Windows is installed) is known as C:, or drive C.

In Unix-like operating systems, however, partitions appear as ordinary directories under the root directory - we'll cover this later.

In the next section, we'll dive deeper into partitioning and get to know two concepts that will change your perspective on file systems: system firmware and booting.

Are you ready?

Away we go! 🏊♂️

Partitioning schemes, system firmware, and booting

When partitioning a storage device, we have two partitioning methods (or schemes 🙄) to choose from:

- Master boot record (MBR) Scheme

- GUID Partition Table (GPT) Scheme

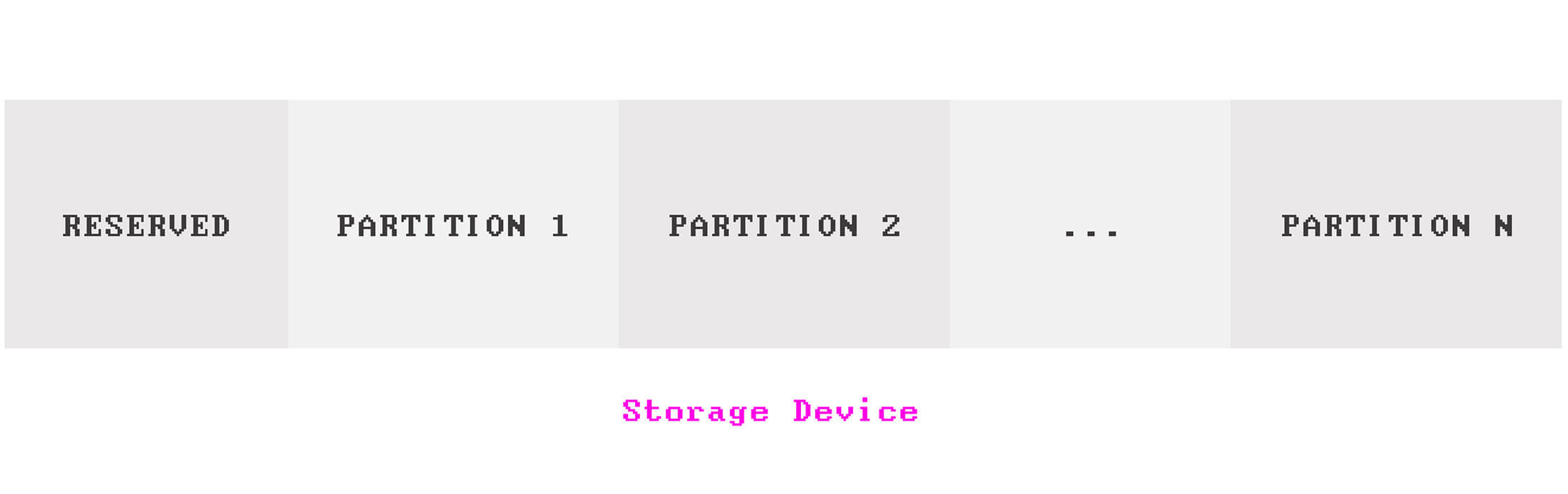

Regardless of what partitioning scheme you choose, the first few blocks on the storage device will always contain critical data about your partitions.

The system's firmware uses these data structures to boot up the operating system on a partition.

Wait, what is the system firmware? You may ask.

Here's an explanation:

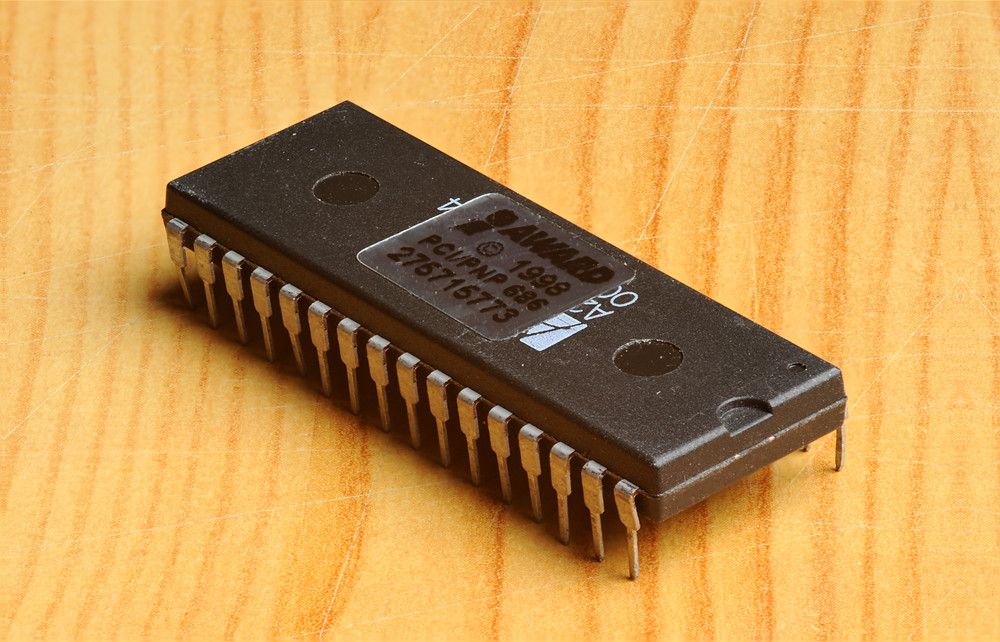

A firmware is a low-level software embedded into electronic devices to operate the device, or bootstrap another program to do it.

Firmware exists in computers, peripherals (keyboards, mice, and printers), or even electronic home appliances.

In computers, the firmware provides a standard interface for complex software like an operating system to boot up and work with hardware components.

However, on simpler systems like a printer, the firmware is the operating system. The menu you use on your printer is the interface of its firmware.

Hardware manufacturers make firmware based on two specifications:

- Basic Input/Output (BIOS)

- Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI)

Firmwares - BIOS-based or UEFI-based - reside on a non-volatile memory, like a flash ROM attached to the motherboard.

[CC BY 2.0](https://www.flickr.com/photos/computerhotline/5794340306">BIOS By Thomas Bresson, Licensed under <a href="https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

[CC BY 2.0](https://www.flickr.com/photos/computerhotline/5794340306">BIOS By Thomas Bresson, Licensed under <a href="https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

When you press the power button on your computer, the firmware is the first program to run.

The mission of the firmware (among other things) is to boot up the computer, run the operating system, and pass it the control of the whole system.

A firmware also runs pre-OS environments (with network support), like recovery or diagnostic tools, or even a shell to run text-based commands.

The first few screens you see before your Windows logo appears are the output of your computer's firmware, verifying the health of hardware components and the memory.

The initial check is confirmed with a beep (usually on PCs), indicating everything is good to go.

MBR partitioning and BIOS-based firmware

MBR partitioning scheme is a part of the BIOS specifications and is used by BIOS-based firmware.

On MBR-partitioned disks, the first sector on the storage device contains essential data to boot up the system.

This sector is called MBR.

MBR contains the following information:

- The boot loader, which is a simple program (in machine code) to initiate the first stage of the booting process

- A partition table, which contains information about your partitions.

BIOS-based firmware boots the system differently than UEFI-based firmware.

Here's how it works:

Once the system is powered on, the BIOS firmware starts and loads the boot loader program (contained in MBR) onto memory. Once the program is on the memory, the CPU begins executing it.

Having the boot loader and the partition table in a predefined location like MBR enables BIOS to boot up the system without having to deal with any file.

If you are curious about how the CPU executes the instructions residing in the memory, you can read this beginner-friendly and fun guide on how the CPU works.

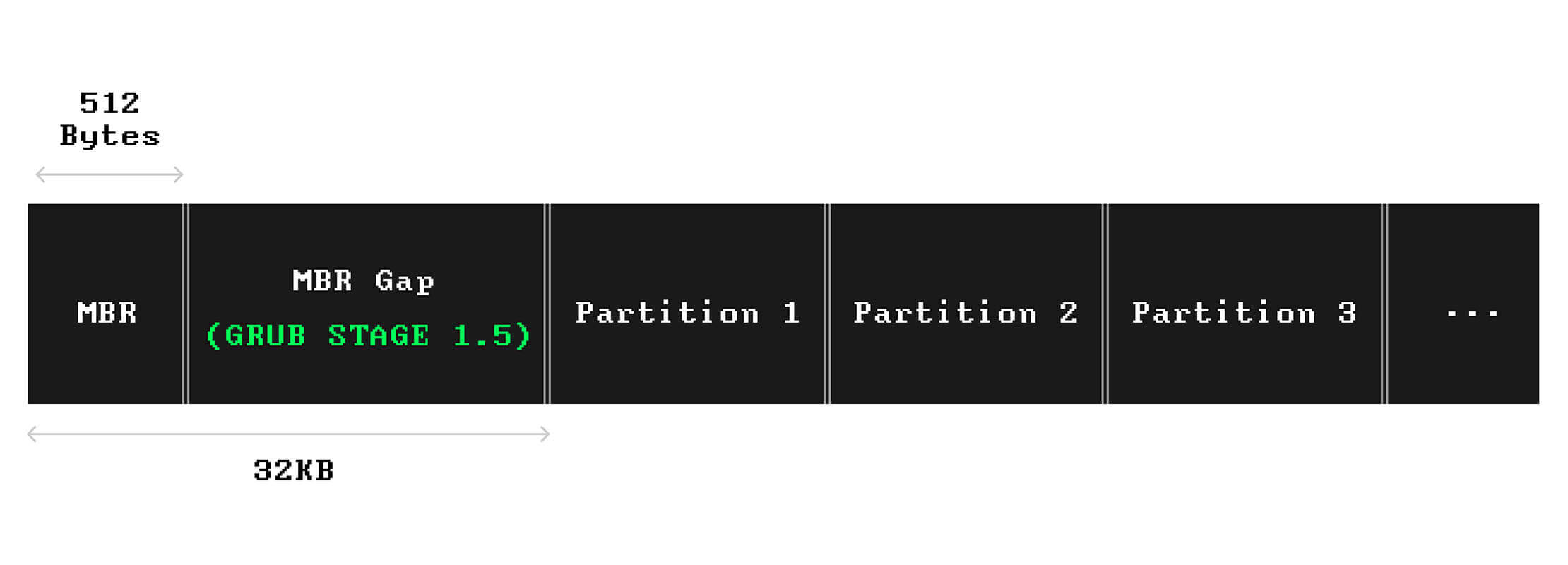

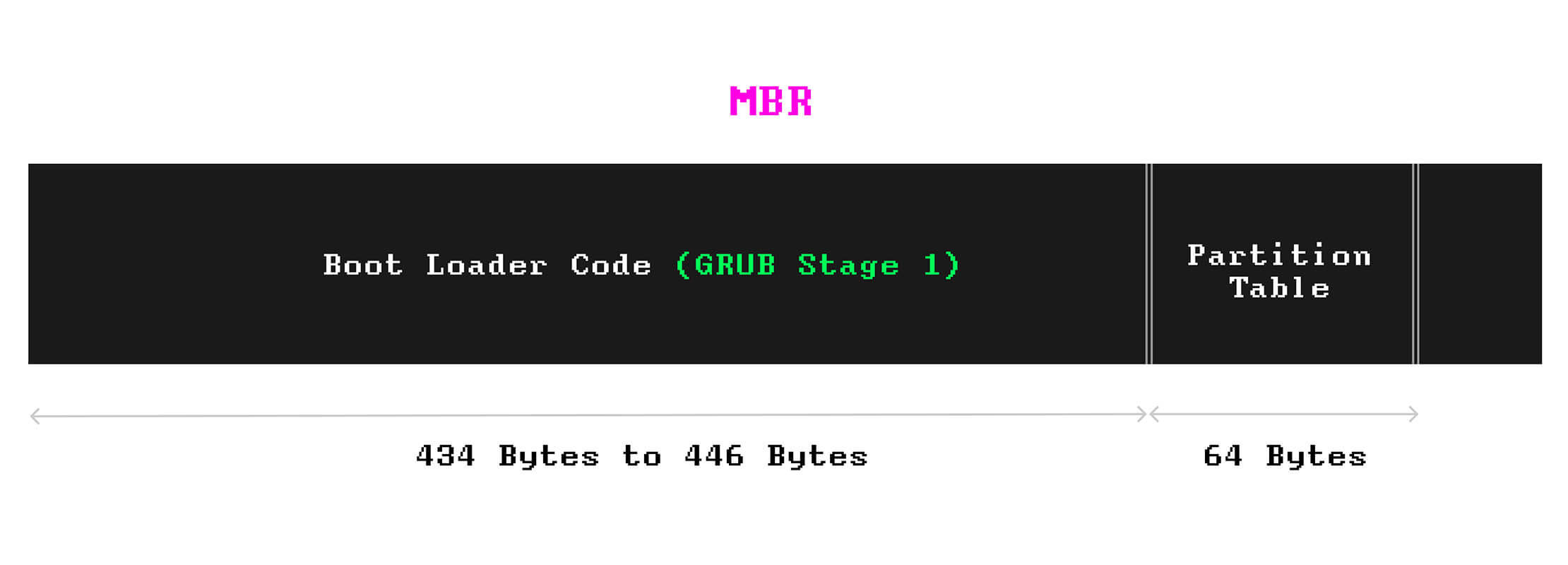

The boot loader code in the MBR takes between 434 bytes to 446 bytes of the MBR space (out of 512b). Additionally, 64 bytes are allocated to the partition table, which can contain information about a maximum of four partitions.

446 bytes isn't big enough to accommodate too much code, though. That said, sophisticated boot loaders like GRUB 2 on Linux split their functionality into pieces or stages.

The smallest piece of code known as the first-stage boot loader is stored in the MBR. It's usually a simple program, which doesn't require much space.

The responsibility of the first-stage boot loader is to initiate the next (and more complicated) stages of the booting process.

Immediately after the MBR, and before the first partition starts, there's a small space, around 1MB, called the MBR gap.

MBR gap can be used to place another piece of the boot loader program if needed.

A boot loader, such as GRUB 2, uses the MBR gap to store another stage of its functionality. GRUB calls this the stage 1.5 boot loader, which contains a file system driver.

Stage 1.5 enables the next stages of GRUB to understand the concept of files, rather than loading raw instructions from the storage device (like the first-stage boot loader).

The second stage boot loader, which is now capable of working with files, can load the operating system's boot loader file to boot up the respective operating system.

This is when the operating system's logo fades in...

Here's the layout of an MBR-partition storage device:

And if we magnify the MBR, its content would look like this:

Although MBR is simple and widely supported, it has some limitations 😑.

MBR's data structure limits the number of partitions to only four primary partitions.

A common workaround is to make an extended partition beside the primary partitions, as long as the total number of partitions won't exceed four.

An extended partition can be split into multiple logical partitions. Making extended partitions is different across operating systems. Over this quick guide Microsoft explains how it should be done on Windows.

When making a partition, you can choose between primary and extended.

After this is solved, we'll encounter the second limitation.

Each partition can be a maximum of 2TiB 🙄.

And wait, there's more!

The content of the MBR sector has no backup 😱, meaning if MBR gets corrupted due to an unexpected reason, we'll have to find a way to recycle that useless piece of hardware.

This is where GPT partitioning stands out 😎.

GPT partitioning and UEFI-based firmware

The GPT partitioning scheme is more sophisticated than MBR and doesn't have the limitations of MBR.

For instance, you can have as many partitions as your operating system allows.

And every partition can be the size of the biggest storage device available in the market - actually a lot more.

GPT is gradually replacing MBR, although MBR is still widely supported across old PCs and new ones.

As mentioned earlier, GPT is a part of the UEFI specification, which is replacing the good old BIOS.

That means that UEFI-based firmware uses a GPT-partitioned storage device to handle the booting process.

Many hardware and operating systems now support UEFI and use the GPT scheme to partition storage devices.

In the GPT partitioning scheme, the first sector of the storage device is reserved for compatibility reasons with BIOS-based systems. The reason is some systems might still use a BIOS-based firmware but have a GPT-partitioned storage device.

This sector is called Protective MBR. (This is where the first-stage boot loader would reside in an MBR-partitioned disk)

After this first sector, the GPT data structures are stored, including the GPT header and the partition entries.

The GPT entries and the GPT header are backed up at the end of the storage device, so they can be recovered if the primary copy gets corrupted.

This backup is called Secondary GPT.

The layout of a GPT-partitioned storage device looks like this:

In GPT, all the booting services (boot loaders, boot managers, pre-os environments, and shells) live in a dedicated partition called EFI System Partition (ESP), which UEFI firmware can use.

ESP even has its own file system, which is a specific version of FAT. On Linux, ESP resides under the /sys/firmware/efi path.

If this path cannot be found on your system, then your firmware is probably BIOS-based firmware.

To check it out, you can try to change the directory to the ESP mount point, like so:

cd /sys/firmware/efi

UEFI-based firmware assumes that the storage device is partitioned with GPT and looks up the ESP in the GPT partition table.

Once the EFI partition is found, it looks for the configured boot loader - usually, a file ending with .efi.

UEFI-based firmware gets the booting configuration from NVRAM (a non-volatile RAM).

NVRAM contains the booting settings and paths to the operating system boot loader files.

UEFI firmware can do a BIOS-style boot too (to boot the system from an MBR disk) if configured accordingly.

You can use the parted command on Linux to see what partitioning scheme is used for a storage device.

sudo parted -l

And the output would be something like this:

Model: Virtio Block Device (virtblk)

Disk /dev/vda: 172GB

Sector size (logical/physical): 512B/512B

Partition Table: gpt

Disk Flags:

Number Start End Size File system Name Flags

14 1049kB 5243kB 4194kB bios_grub

15 5243kB 116MB 111MB fat32 msftdata

1 116MB 172GB 172GB ext4

Based on the above output, the storage device's ID is /dev/vda with a capacity of 172GB. The storage device is partitioned based on GPT and has three partitions; The second and third partitions are formatted based on the FAT32 and EXT4 file systems respectively.

Having a BIOS GRUB partition implies the firmware is still BIOS-based firmware.

Let's confirm that with the dmidecode command like so:

sudo dmidecode -t 0

And the output would be:

# dmidecode 3.2

Getting SMBIOS data from sysfs.

SMBIOS 2.4 present.

...

✅ Confirmed!

Formatting partitions

When partitioning is done, the partitions should be formatted.

Most operating systems allow you to format a partition based on a set of file systems.

For instance, if you are formatting a partition on Windows, you can choose between FAT32, NTFS, and exFAT file systems.

Formatting involves the creation of various data structures and metadata used to manage files within a partition.

These data structures are one aspect of a file system.

Let's take the NTFS file system as an example.

When you format a partition to NTFS, the formatting process places the key NTFS data structures and the Master file table (MFT) on the partition.

Alright, let's get back file systems with our new background about partitioning, formatting, and booting.

How it started, how it's going

A file system is a set of data structures, interfaces, abstractions, and APIs that work together to manage any type of file on any type of storage device, in a consistent manner.

Each operating system uses a particular file system to manage the files.

In the early days, Microsoft used FAT (FAT12, FAT16, and FAT32) in the MS-DOS and Windows 9x family.

Starting from Windows NT 3.1, Microsoft developed New Technology File System (NTFS), which had many advantages over FAT32, such as supporting bigger files, allowing longer filenames, data encryption, access management, journaling, and a lot more.

NTFS has been the default file system of the Window NT family (2000, XP, Vista, 7, 10, etc.) ever since.

NTFS isn’t suitable for non-Windows environments, though 🤷🏻.

For instance, you can only read the content of an NTFS-formatted storage device (like flash memory) on a Mac OS, but you won’t be able to write anything to it - unless you install an NTFS driver with write support.

Or you can just use the exFat file system.

Extended File Allocation Table (exFAT) is a lighter version of NTFS created by Microsoft in 2006.

exFAT was designed for high-capacity removable devices, such as external hard disks, USB drives, and memory cards.

exFAT is the default file system used by SDXC cards.

Unlike NTFS, exFAT has read and write support on Non-Windows environments as well, including Mac OS — making it the best cross-platform file system for high-capacity removable storage devices.

So basically, if you have a removable disk you want to use on Windows, Mac, and Linux, you need to format it to exFAT.

Apple has also developed and used various file systems over the years, including

Hierarchical File System (HFS), HFS+, and recently Apple File System (APFS).

Just like NTFS, APFS is a journaling file system and has been in use since the launch of OS X High Sierra in 2017.

But how about file systems in Linux distributions?

The Extended File System (ext) family of file systems was created for the Linux kernel - the core of the Linux operating system.

The first version of ext was released in 1991, but soon after, it was replaced by the second extended file system (ext2) in 1993.

In the 2000s, the third extended filesystem (ext3) and fourth extended filesystem (ext4) were developed for Linux with journaling capability.

ext4 is now the default file system in many distributions of Linux, including Debian and Ubuntu.

You can use the findmnt command on Linux to list your ext4-formatted partitions:

findmnt -lo source,target,fstype,used -t ext4

The output would be something like:

SOURCE TARGET FSTYPE USED

/dev/vda1 / ext4 3.6G

Architecture of file systems

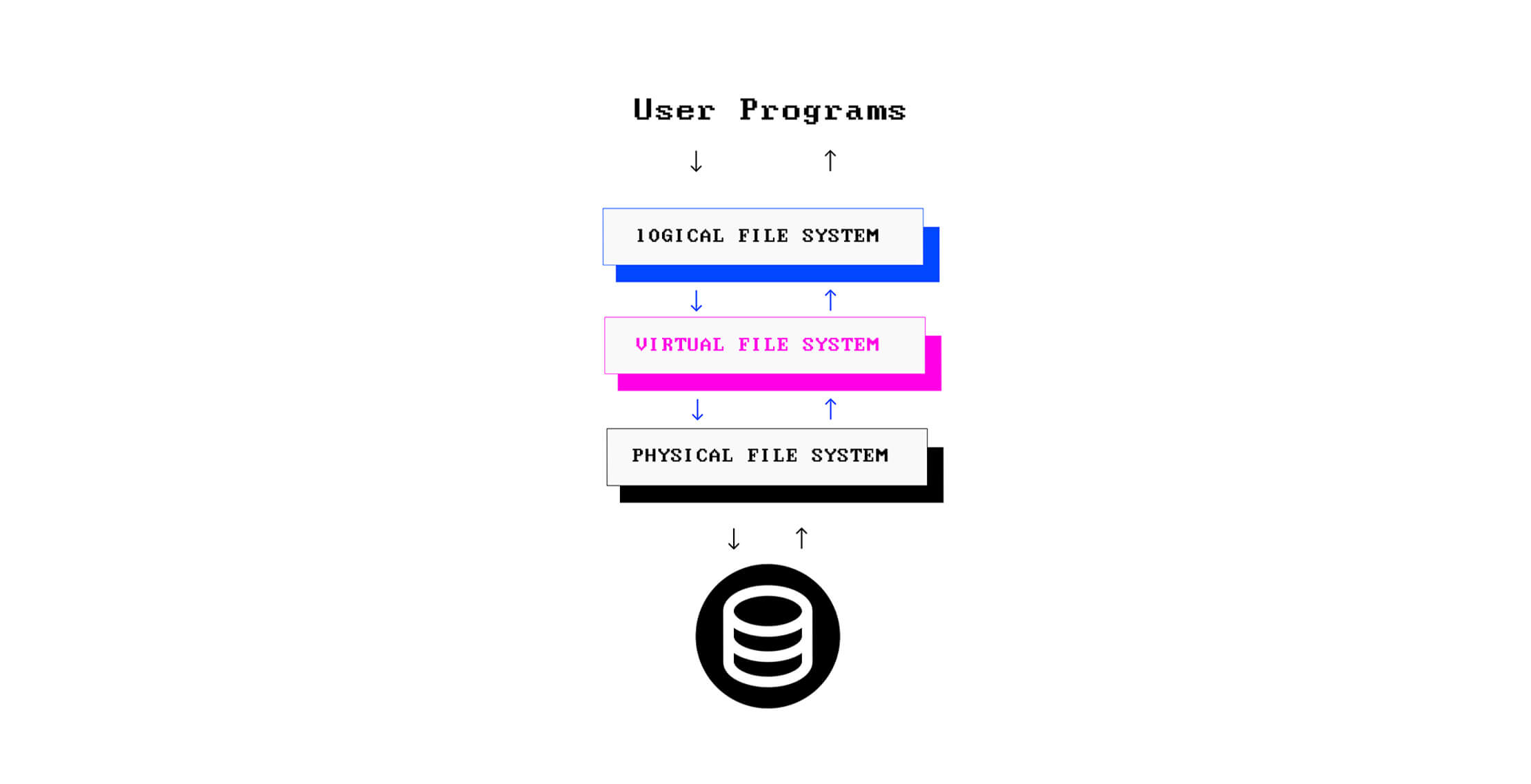

A file system installed on an operating system consists of three layers:

- Physical file system

- Virtual file system

- Logical file system

These layers can be implemented as independent or tightly coupled abstractions.

When people talk about file systems, they refer to one of these layers or all three as one unit.

Although these layers are different across operating systems, the concept is the same.

The physical layer is the concrete implementation of a file system; It's responsible for data storage and retrieval and space management on the storage device (or precisely: partitions).

The physical file system interacts with the storage hardware via device drivers.

The next layer is the virtual file system or VFS.

The virtual file system provides a consistent view of various file systems mounted on the same operating system.

So does this mean an operating system can use multiple file systems at the same time?

The answer is yes!

It's common for a removable storage medium to have a different file system than that of a computer.

For instance, on Windows (which uses NTFS as the primary file system), a flash memory might have been formatted to exFAT or FAT32.

That said, the operating system should provide a unified interface between computer programs (file explorers and other apps that work with files) and the different mounted file systems (such as NTFS, APFS, ext4, FAT32, exFAT, and UDF).

For instance, when you open up your file explorer program, you can copy an image from an ext4 file system and paste it over to your exFAT-formatted flash memory - without having to know that files are managed differently under the hood.

This convenient layer between the user (you) and the underlying file systems is provided by the VFS.

A VFS defines a contract that all physical file systems must implement to be supported by that operating system.

However, this compliance isn't built into the file system core, meaning the source code of a file system doesn't include support for every operating system's VFS.

Instead, it uses a file system driver to adhere to the VFS rules of every file system. A driver is a program that enables software to communicate with another software or hardware.

Although VFS is responsible for providing a standard interface between programs and various file systems, computer programs don't interact with VFS directly.

Instead, they use a unified API between programs and the VFS.

Can you guess what it is?

Yes, we're talking about the logical file system.

The logical file system is the user-facing part of a file system, which provides an API to enable user programs to perform various file operations, such as OPEN, READ, and WRITE, without having to deal with any storage hardware.

On the other hand, VFS provides a bridge between the logical layer (which programs interact with) and a set of the physical layer of various file systems.

A high-level architecture of the file system layers

A high-level architecture of the file system layers

What does it mean to mount a file system?

On Unix-like systems, the VFS assigns a device ID (for instance, dev/disk1s1) to each partition or removable storage device.

Then, it creates a virtual directory tree and puts the content of each device under that directory tree as separate directories.

The act of assigning a directory to a storage device (under the root directory tree) is called mounting, and the assigned directory is called a mount point.

That said, on a Unix-like operating system, all partitions and removable storage devices appear as if they are directories under the root directory.

For instance, on Linux, the mounting points for a removable device (such as a memory card), are usually under the /media directory.

That said, once a flash memory is attached to the system, and consequently, auto mounted at the default mounting point (/media in this case), its content would be available under the /media directory.

However, there are times you need to mount a file system manually.

On Linux, it’s done like so:

mount /dev/disk1s1 /media/usb

In the above command, the first parameter is the device ID (/dev/disk1s1), and the second parameter (/media/usb) is the mount point.

Please note that the mount point should already exist as a directory.

If it doesn’t, it has to be created first:

mkdir -p /media/usb

mount /dev/disk1s1 /media/usb

If the mount-point directory already contains files, those files will be hidden for as long as the device is mounted.

Files metadata

File metadata is a data structure that contains data about a file, such as:

- File size

- Timestamps, like creation date, last accessed date, and modification date

- The file's owner

- The file's mode (who can do what with the file)

- What blocks on the partition are allocated to the file

- and a lot more

Metadata isn’t stored with the file content, though. Instead, it’s stored in a different place on the disk - but associated with the file.

In Unix-like systems, the metadata is in the form of data structures, called inode.

Inodes are identified by a unique number called the inode number.

Inodes are associated with files in a table called inode tables.

Each file on the storage device has an inode, which contains information about it such as the time it was created, modified, etc.

The inode also includes the address of the blocks allocated to the file; On the other hand, where exactly it's located on the storage device

In an ext4 inode, the address of the allocated blocks is stored as a set of data structures called extents (within the inode).

Each extent contains the address of the first data block allocated to the file and the number of the continuous blocks that the file has occupied.

Whenever you open a file on Linux, its name is first resolved to an inode number.

Having the inode number, the file system fetches the respective inode from the inode table.

Once the inode is fetched, the file system starts to compose the file from the data blocks registered in the inode.

You can use the df command with the -i parameter on Linux to see the inodes (total, used, and free) in your partitions:

df -i

The output would look like this:

udev 4116100 378 4115722 1% /dev

tmpfs 4118422 528 4117894 1% /run

/dev/vda1 6451200 175101 6276099 3% /

As you can see, the partition /dev/vda1 has a total number of 6,451,200 inodes, of which 3% have been used (175,101 inodes).

To see the inodes associated with files in a directory, you can use the ls command with -il parameters.

ls -li

And the output would be:

1303834 -rw-r--r-- 1 root www-data 2502 Jul 8 2019 wp-links-opml.php

1303835 -rw-r--r-- 1 root www-data 3306 Jul 8 2019 wp-load.php

1303836 -rw-r--r-- 1 root www-data 39551 Jul 8 2019 wp-login.php

1303837 -rw-r--r-- 1 root www-data 8403 Jul 8 2019 wp-mail.php

1303838 -rw-r--r-- 1 root www-data 18962 Jul 8 2019 wp-settings.php

The first column is the inode number associated with each file.

The number of inodes on a partition is decided when you format a partition. That said, as long as you have free space and unused inodes, you can store files on your storage device.

It's unlikely that a personal Linux OS would run out of inodes. However, enterprise services that deal with a large number of files (like mail servers) have to manage their inode quota smartly.

On NTFS, the metadata is stored differently, though.

NTFS keeps file information in a data structure called the Master File Table (MFT).

Every file has at least one entry in MFT, which contains everything about it, including its location on the storage device - similar to the inodes table.

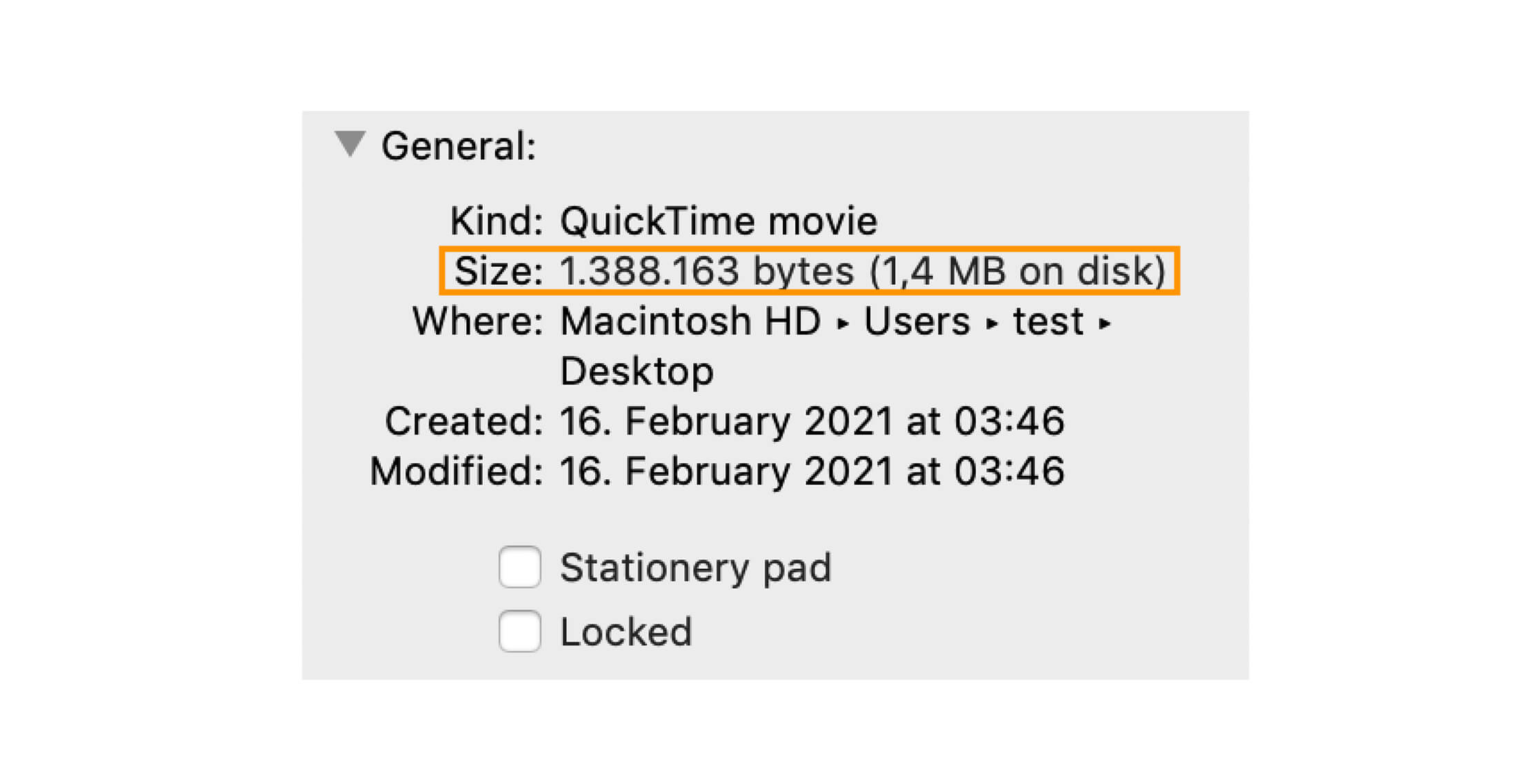

On most operating systems, you can grab metadata via the graphical user interface.

For instance, when you right-click on a file on Mac OS, and select Get Info (Properties in Windows), a window appears with information about the file. This information is fetched from the respective file’s metadata.

Space Management

Storage devices are divided into fixed-sized blocks called sectors.

A sector is the minimum storage unit on a storage device and is between 512 bytes and 4096 bytes (Advanced Format).

However, file systems use a high-level concept as the storage unit, called blocks.

Blocks are an abstraction over physical sectors; Each block usually consists of multiple sectors.

Depending on the file size, the file system allocates one or more blocks to each file.

Speaking of space management, the file system is aware of every used and unused block on the partitions, so it’ll be able to allocate space to new files or fetch the existing ones when requested.

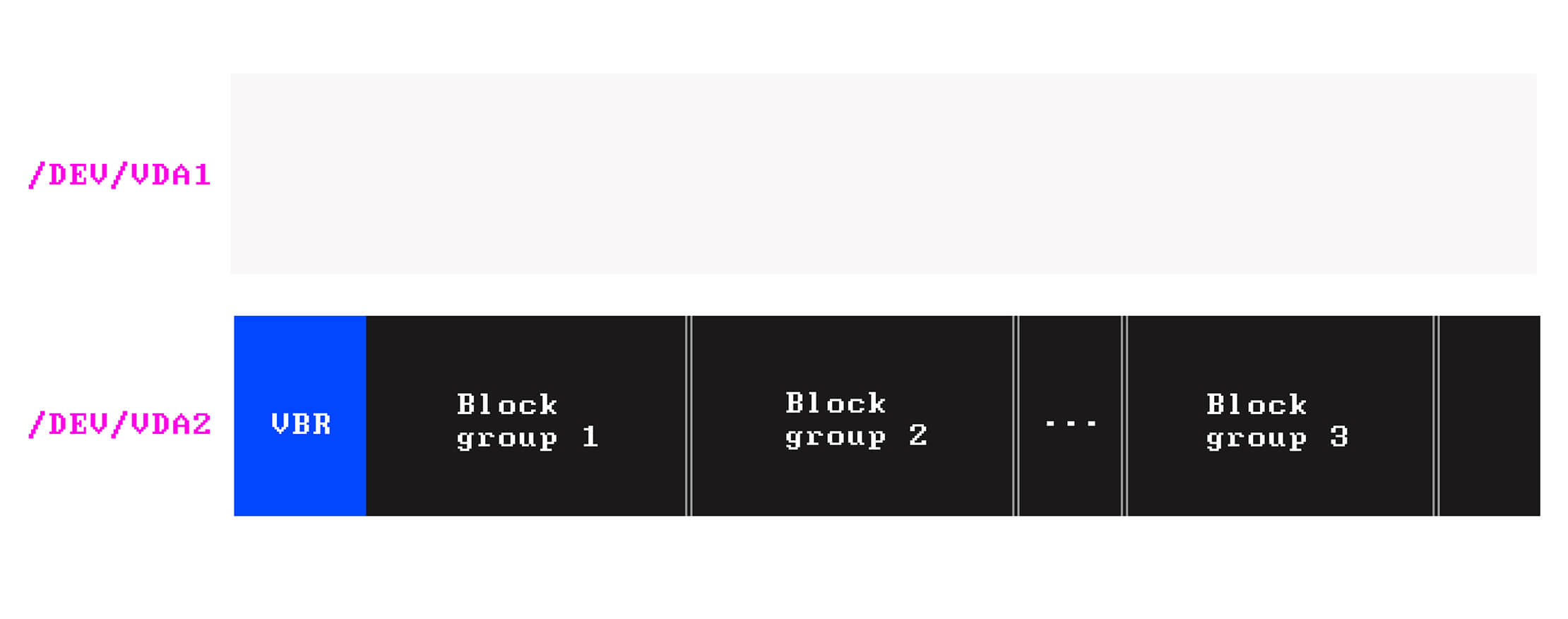

The most basic storage unit in ext4-formatted partitions is the block. However, the contiguous blocks are grouped into block groups for easier management.

The layout of a block group within an ext4 partition

The layout of a block group within an ext4 partition

Each block group has its own data structures and data blocks.

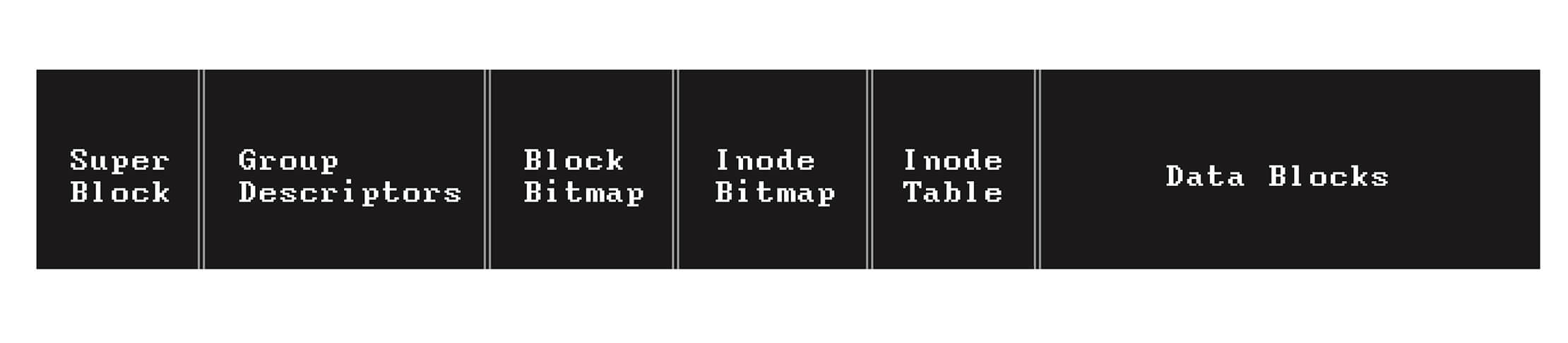

Here are the data structures a block group can contain:

- Super Block: a metadata repository, which contains metadata about the entire file system, such as the total number of blocks in the file system, total blocks in block groups, inodes, and more. Not all block groups contain the superblock, though. A certain number of block groups store a copy of the super as a backup.

- Group Descriptors: Group descriptors also contain bookkeeping information for each block group

- Inode Bitmap: Each block group has its own inode quota for storing files. A block bitmap is a data structure used to identify used and unused inodes within the block group.

1denotes used and0denotes unused inode objects. - Block Bitmap: a data structure used to identify used & unused data blocks within the block group.

1denotes used and0denotes unused data blocks - Inode Table: a data structure that defines the relation of files and their inodes. The number of inodes stored in this area is related to the block size used by the file system.

- Data Blocks: This is the zone within the block group where file contents are stored.

Ext4 file system even takes one step further (comparing to ext3), and organizes block groups into a bigger group called flex block groups.

The data structures of each block group, including the block bitmap, inode bitmap, and inode table, are concatenated and stored in the first block group within each flex block group.

Having all the data structures concatenated in one block group (the first one) frees up more contiguous data blocks on other block groups within each flex block group.

These concepts might be confusing, but you don't have to master every bit of them. It's just to depict the depth of file systems.

The layout of the first block group looks like this:

The layout of the first block in an ext4 flex block group

The layout of the first block in an ext4 flex block group

When a file is being written to a disk, it is written to one or more blocks within a block group.

Managing files at the block group level improves the performance of the file system significantly, as opposed to organizing files as one unit.

Size vs size on disk

Have you ever noticed that your file explorer displays two different sizes for each file: size, and size on disk.

Size and Size on disk

Size and Size on disk

Why are size and size on disk slightly different? You may ask.

Here’s an explanation:

We already know depending on the file size, one or more blocks are allocated to a file.

One block is the minimum space that can be allocated to a file. This means the remaining space of a partially-filled block cannot be used by another file. This is the rule!

Since the size of the file isn't an integer multiple of blocks, the last block might be partially used, and the remaining space would remain unused - or would be filled with zeros.

So "size" is basically the actual file size, while "size on disk" is the space it has occupied, even though it’s not using it all.

You can use the du command on Linux to see it yourself.

du -b "some-file.txt"

The output would be something like this:

623 icon-link.svg

And to check the size on disk:

du -B 1 "icon-link.svg"

Which will result in:

4096 icon-link.svg

Based on the output, the allocated block is about 4kb, while the actual file size is 623 bytes. This means each block size on this operating system is 4kb.

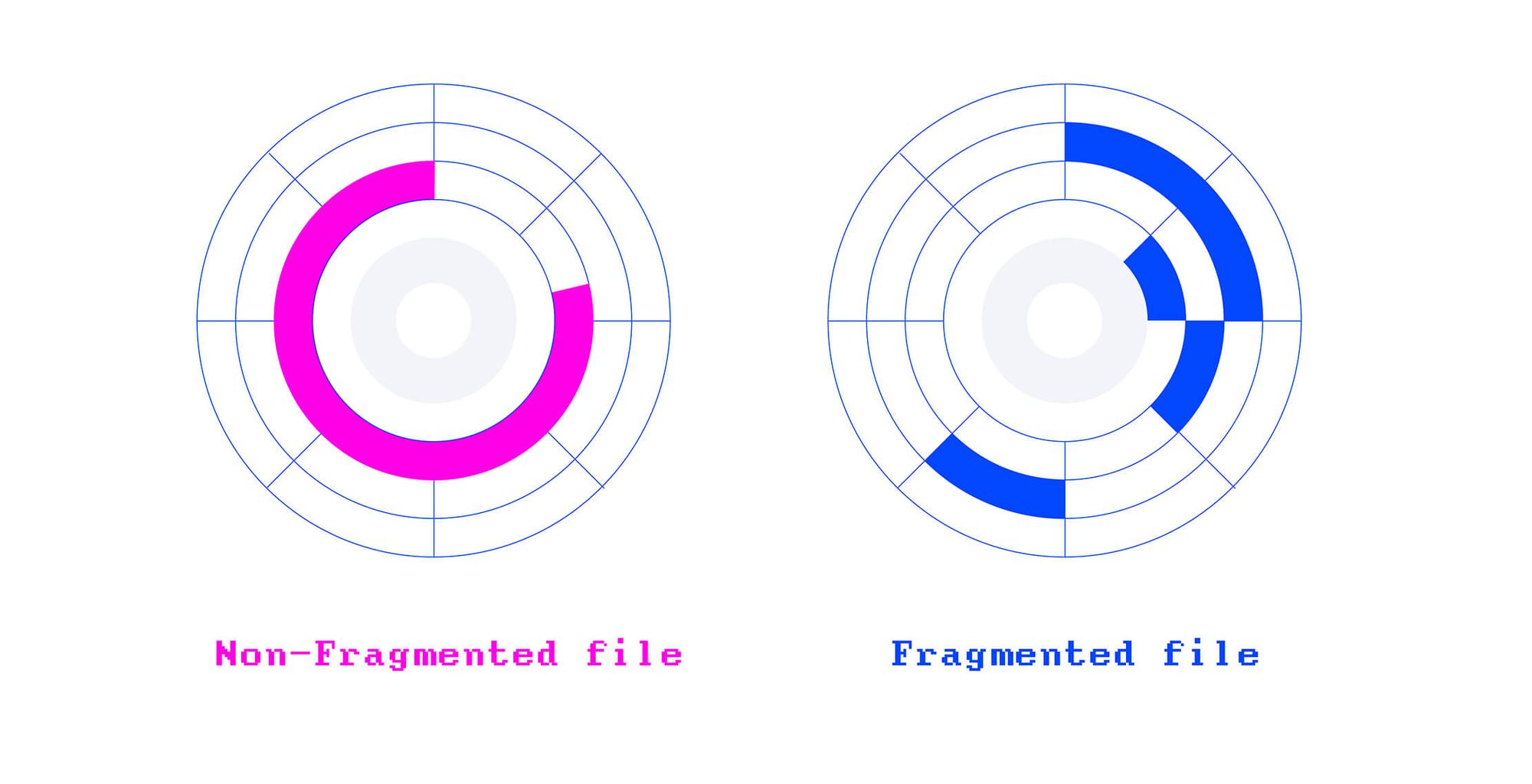

What is disk fragmentation?

Over time, new files are written to the disk, existing files get bigger, shrunk, or deleted.

These frequent changes in the storage medium leave many small gaps (empty spaces) between files. These gaps are due to the same reason file size and file size on disk are different. Some files won't fill up the full block, and lots of space will be wasted. And over time there' won't be enough consequent blocks to store new files.

That's when new files need to be stored as fragments.

File Fragmentation occurs when a file is stored as fragments on the storage device because the file system cannot find enough contiguous blocks to store the whole file in a row.

An example of a fragmented and non-fragmented file

An example of a fragmented and non-fragmented file

Let's make it more clear with an example.

Imagine you have a Word document named myfile.docx.

myfile.docx is initially stored in a few contiguous blocks on the disk; Let's say this is how the blocks are named: LBA250, LBA251, and LBA252.

Now, if you add more content to myfile.docx and save it, it will need to occupy more blocks on the storage medium.

Since myfile.docx is currently stored on LBA250, LBA251, and LBA252, the new content should preferably sit within LBA253 and so forth - depending on how many more blocks are needed to accommodate the new changes.

Now, imagine LBA253 is already taken by another file (maybe it’s the first block of another file). In that case, the new content of myfile.docx has to be stored on different blocks somewhere else on the disks, for instance, LBA312 and LBA313.

myfile.docx got fragmented 💔.

File fragmentation puts a burden on the file system because every time a fragmented file is requested by a user program, the file system needs to collect every piece of the file from various locations on a disk.

This overhead applies to saving the file back to the disk as well.

The fragmentation might also occur when a file is written to the disk for the first time, probably because the file is huge and not many continuous blocks are left on the partition.

Fragmentation is one of the reasons some operating systems get slow as the file system ages.

Should We Care About Fragmentation these days?

The short answer is: not anymore!

Modern file systems use smart algorithms to avoid (or early-detect) fragmentation as much as possible.

Ext4 also does some sort of preallocation, which involves reserving blocks for a file before they are actually needed - making sure the file won't get fragmented if it gets bigger over time.

The number of the preallocated blocks is defined in the length field of the file's extent of its inode object.

Additionally, ext4 uses an allocation technique called delayed allocation.

The idea is instead of writing to data blocks one at a time during a write, the allocation requests are accumulated in a buffer and are written to the disk at once.

Not having to call the file system's block allocator on every write request helps the file system make better choices with distributing the available space. For instance, by placing large files apart from smaller files.

Imagine that a small file is located between two large files. Now, if the small file is deleted, it leaves a small space between the two files.

Spreading the files out in this manner leaves enough gaps between data blocks, which helps the filesystem manage (and avoid) fragmentation more easily.

Delayed allocation actively reduces fragmentation and increases performance.

Directories

A Directory (Folder in Windows) is a special file used as a logical container to group files and directories within a file system.

On NTFS and Ext4, directories and files are treated the same way. That said, directories are just files that have their own inode (on Ext4) or MFT entry (on NTFS).

The inode or MFT entry of a directory contains information about that directory, as well as a collection of entries pointing to the files "under" that directory.

The files aren't literally contained within the directory, but they are associated with the directory in a way that they appear as directory's children at a higher level, such as in a file explorer program.

These entries are called directory entries. Directory entries contain file names mapped to their inode/MFT entry.

In addition to the directory entries, there are two more entries. The . entry, which points to the directory itself, and .., which points to the parent directory of this directory.

On Linux, you can use the ls in a directory to see the directory entries with their associated inode numbers:

ls -lai

And the output would be something like this:

63756 drwxr-xr-x 14 root root 4096 Dec 1 17:24 .

2 drwxr-xr-x 19 root root 4096 Dec 1 17:06 ..

81132 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Feb 18 06:25 backups

81020 drwxr-xr-x 14 root root 4096 Dec 2 07:01 cache

81146 drwxrwxrwt 2 root root 4096 Oct 16 21:43 crash

80913 drwxr-xr-x 46 root root 4096 Dec 1 22:14 lib

...

Rules for naming files

Some file systems enforce limitations on filenames.

The limitation can be in the length of the filename or filename case sensitivity.

For instance, in NTFS (Windows) and APFS (Mac) file systems, MyFile and myfile refer to the same file, while on ext4 (Linux), they point to different files.

Why does this matter? You may ask.

Imagine that you’re creating a web page on your Windows machine. The web page contains your company logo, which is a PNG file, like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Products - Your Website</title>

</head>

<body>

<!--SOME CONTENT-->

<img src="img/logo.png">

<!--SOME MORE CONTENT-->

</body>

</html>

If the actual file name is Logo.png (note the capital L), you can still see the image when you open your web page on your web browser (on your Windows machine).

However, once you deploy it to a Linux server and view it live, you'll see a broken image.

Why?

Because in Linux (ext4 file system) logo.png and Logo.png point to two different files.

So keep that in mind when developing on Windows and deploying to a Linux server.

Rules for file size

One important aspect of file systems is the maximum file size they support.

An old file system like FAT32 (used by MS-DOS +7.1, Windows 9x family, and flash memories) can’t store files more than 4 GB, while its successor, NTFS allows file sizes to be up to 16 EB (1000 TB).

Like NTFS, exFAT allows a file size of 16 EB too. This makes exFAT an ideal option for storing massive data objects, such as video files.

Practically, there’s no limitation on the file size in the exFAT and NTFS file systems.

Linux’s ext4 and Apple’s APFS support files up to 16 TiB and 8 EiB respectively.

File manager programs

As you know, the logical layer of the file system provides an API to enable user applications to perform file operations, such as read, write, delete, and execute operations.

The file system’s API is a low-level mechanism, though, designed for computer programs, runtime environments, and shells - not designed for daily use.

That said, operating systems provide convenient file management utilities out of the box for your day-to-day file management.

For instance, File Explorer on Windows, Finder on Mac OS, and Nautilus on Ubuntu are examples of file manager programs.

These utilities use the logical file system’s API under the hood.

Apart from these GUI tools, operating systems expose the file system’s APIs via the command-line interfaces too, like Command Prompt on Windows, and Terminal on Mac and Linux.

These text-based interfaces help users do all sorts of file operations as text commands - Like how we did in the previous examples.

File access management

Not everyone should be able to remove or modify a file they don’t own or are not authorized to do so.

Modern file systems provide mechanisms to control users’ access and capabilities concerning files.

The data regarding user permissions and file ownership is stored in a data structure called Access-Control List (ACL) on Windows or Access-Control Entries (ACE) on Unix-like operating systems (Linux and Mac OS).

This feature is also available in the CLI (Command prompt or Terminal), where a user can change file ownerships or limit permissions of each file right from the command line interface.

For instance, a file owner (on Linux or Mac) can configure a file to be available to the public, like so:

chmod 777 myfile.txt

777 means everyone can do every operation (read, write, execute) on myfile.txt. Please note this is just an example, and you should not set a file's permission to 777.

Maintaining data integrity

Let’s suppose you've been working on your thesis for a month now. One day, you open the file, make some changes and save it.

Once you save the file, your word processor program sends a “write” request to the file system’s API (the logical file system).

The request is eventually passed down to the physical layer to store the file on several blocks.

But what if the system crashes while the older version of the file is being replaced with the new version?

In older file systems (like FAT32 or ext2) the data would be corrupted because it was partially written to the disk.

This is less likely to happen with modern file systems as they use a technique called journaling.

Journaling file systems record every operation that’s about to happen in the physical layer but hasn’t happened yet.

The main purpose is to keep track of the changes that haven't yet been committed to the file system physically.

The journal is a special allocation on the disk where each writing attempt is first stored as a transaction.

Once the data is physically placed on the storage device, the change is committed to the filesystem.

In case of a system failure, the file system will detect the incomplete transaction and roll it back as if it never happened.

That said, the new content (that was being written) may still be lost, but the existing data would remain intact.

Modern file systems such as NTFS, APFS, and ext4 (even ext3) use journaling to avoid data corruption in case of system failure.

Database File Systems

Typical file systems organize files as directory trees.

To access a file, you traverse to the respective directory, and you'll have it.

cd /music/country/highwayman

However, in a database file system, there’s no concept of paths and directories.

The database file system is a faceted system which groups files based on various attributes and dimensions.

For instance, MP3 files can be listed by artist, genre, release year, and album - at the same time!

A database file system is more like a high-level application to help you organize and access your files more easily and more efficiently. However, you won’t be able to access the raw files outside of this application.

A database file system cannot replace a typical file system, though. It’s just a high-level abstraction for easier file management on some systems.

The iTunes app on Mac OS is a good example of a database file system.

Wrapping Up

Wow! You made it to the end, which means you know a lot more about file systems now. But I'm sure this won't be the end of your file system studies.

So again - can we describe what a file system is and how it works in one sentence?

We can't! 😁

But let's finish this post with the brief description I used at the beginning:

A file system defines how files are named, stored, and retrieved from the storage device.

Alright, I think it does it for this write-up. If you notice something is missing or that I've gotten wrong, please let me in the comments below. That would help me and others too!

By the way, if you like more comprehensive guides like this one, visit my website decodingweb. dev and follow me on Twitter because, besides freeCodeCamp, those are the channels I use to share my everyday findings.

Thanks for reading, and enjoy learning! 😃