Execution Context is one of the most fundamental yet most misunderstood concepts in JavaScript. It defines how JavaScript code is evaluated and executed, and it plays a central role in determining how variables, functions, and scope behave.

Many core JavaScript concepts such as scope, hoisting, and closures are closely tied to execution context. Although these topics are often introduced separately, they are all part of the same underlying mechanism. Without a clear understanding of execution context, these concepts can feel disconnected or confusing.

In this handbook, we’ll take a structured and practical approach to understanding execution context in JavaScript. We’ll explore how execution contexts are created, how they work during code execution, and how they explain common JavaScript behaviors.

By the end of this guide, you’ll have a solid mental model of execution context and a stronger foundation for understanding JavaScript at a deeper level.

Here’s What We’ll Cover:

Prerequisites

To follow along and get the most out of this guide, you should have:

Basic JavaScript (ES6-style) knowledge

Browser and Node.js Environment

I’ve also created a video to go along with this handbook. If you’re the type who likes to learn from video as well as text, you can check it out here:

Note: While prior knowledge of Scope, Hoisting, and Closures is helpful, it's not required. This guide will teach you these concepts through the lens of Execution Context and may even clarify misconceptions you might have about them.

How JavaScript Actually Runs

Before diving into Execution Context, let's take a step back and understand how JavaScript actually runs – whether in a browser or in a terminal environment. You might wonder why I'm mentioning the terminal. Well, JavaScript now also runs outside the browser through Node.js. So let's first explore how that happens behind the scenes. When it reaches the browser (or in the case of Node.js, the server), the code you write in JavaScript is ultimately executed by the computer. Here's the important part - computers don't understand JavaScript. They only understand binary or machine language. So somehow, the browser has to translate your JavaScript code into machine language so that the computer can actually run it.

That means there must be some kind of mechanism inside the browser – or in the Node.js runtime – that performs this translation from your programming language to machine language.

The JavaScript Engine

That mechanism inside the browser is called the JavaScript Engine. In Google Chrome, this engine is known as the V8 Engine. Other browsers use their own engines – Firefox uses SpiderMonkey, Internet Explorer uses Chakra, and Safari uses JavaScriptCore.

No matter which engine it is, every browser has one, and they all perform the same core task: converting your JavaScript code into machine language. Different browsers may implement this process in their own way, but all of them follow the same standard, known as the ECMAScript specification.

ECMAScript is basically the official standard that defines how JavaScript should work – like ES5, ES6, and so on. Since each browser's engine implements the standard slightly differently, sometimes the same piece of code may produce slightly different outputs in different browsers.

Anyway, once your code reaches the browser, it's handed over to the browser's JavaScript engine. The engine then converts that code into machine language, which the computer can finally understand. And that's how you get to see the output displayed on your screen.

That's the overall top-level view of how JavaScript code runs. Now, as a programmer, you don't really need to understand what happens at the hardware level, because your focus isn't building hardware – you're an application developer. What truly matters for you, as a JavaScript developer, is understanding what happens inside the engine when it runs your code. In other words, you need a clear picture of how the JavaScript engine actually compiles and executes your code. That's the foundation of everything.

Node.js and V8

Before we dive deeper, there's one important thing to mention. I've been talking mostly about browsers, so you might be wondering what happens in the case of Node.js? Well, Node.js actually uses the same V8 engine that powers Google Chrome.

Ryan Dahl, the creator of Node.js, is a brilliant programmer. What he did was take Chrome's V8 engine – which was already built, tested, and extremely fast – and used it outside the browser. V8 is one of the most powerful and highly optimized compilers in existence. It converts JavaScript into machine language with incredible speed and efficiency.

That's why Google Chrome performs so well – because of the V8 engine. Ryan Dahl realized that V8 was already the best engine out there. So he thought, if he could extract it and use it outside the browser, he wouldn't need to build a new engine from scratch. The compilation part would already be handled by V8. Since V8 is written in C++, Ryan integrated it directly into his own C++ program. In other words, his C++ code and the V8 engine were combined, and that's how the Node.js runtime was created.

How the JavaScript Engine Compiles Code

Now, let's take a look at what actually happens inside a JavaScript engine when it compiles JavaScript code.

To understand that, we need to start with a bit of history. When JavaScript was first introduced, it was an interpreted language, meaning there was no compilation process. There wasn't a compiler to convert JavaScript into efficient machine-level code. And here, we come across two important terms -

Interpretation

Compilation

At first, interpretation and compilation might sound like the same thing – because both convert your code into machine code, right? That's true in essence, but the way they work is completely different.

Interpretation vs Compilation

Here's what you need to understand. Let’s say you have some JavaScript code that you wrote. This code is readable by humans, but the computer doesn't understand it. Computers only understand binary (zeros and ones). That's machine language, and while the computer understands it perfectly, humans can't read it. So, your job is to take this human-readable JavaScript code and convert it into machine code, so the computer can understand what you're asking it to do.

There are three main ways to perform this conversion:

Interpretation

Compilation

A hybrid approach (a mixture of both).

Back in the 90s, JavaScript used to be a purely interpreted language. But in recent times, modern JavaScript engines use a combination of both interpretation and compilation to translate code into machine language. The language itself hasn't changed – it's still JavaScript. But the way it's implemented has evolved dramatically.

How Interpretation Works

Let’s see how an interpreter actually works, meaning how JavaScript code gets converted into machine code through interpretation.

Inside the interpreter, there is already a predefined set of machine-level instructions for every command or expression you can write in JavaScript. To understand this, imagine a piece of JavaScript code that contains several lines of instructions.

The interpreter already knows the machine-level operations that correspond to each of these lines. For example, when two numbers are added, that is an arithmetic operation. When a console.log statement is used, that is an instruction to print something on the screen.

A real program can contain many such instructions. For every one of these operations, the interpreter has a predefined binary or machine-code equivalent. This tells the computer exactly how to execute that specific instruction. When you run a program, the interpreter starts from the very first line and executes the code line by line.

It looks at the first line, recognizes the operation being performed, translates that instruction into machine code, and executes it immediately. Once that line finishes executing, the interpreter moves to the next line. If the next line is a console.log statement, the interpreter translates and executes that instruction as well. This process continues line by line until the program finishes.

But there’s a drawback to this approach: this process is relatively slow. Because the interpreter translates and executes one line at a time, it has to repeatedly switch between reading the source code and executing it. This constant back-and-forth makes pure interpretation significantly slower. This is one of the reasons JavaScript was noticeably slow back in the 90s.

At the same time, interpretation has a major advantage. Since the interpreter executes code one instruction at a time, it can stop immediately if it encounters an error and report exactly where that error occurred. This makes debugging much easier, because developers can quickly identify the problematic line, fix it, and run the code again. So the trade-off is simple: interpretation makes JavaScript easy to debug, but it comes at the cost of slower execution.

How Compilation Works

To overcome that slowness, the concept of compilation was introduced. A compiler works differently: instead of executing code line by line, it takes the entire program at once, translates the whole thing into machine code, and then runs it line by line from that compiled version. This makes the process much faster compared to interpretation.

In this process, the program is first converted into machine code in one go. Only after that conversion is complete does execution begin. So rather than constantly translating and executing at the same time, the compiler finishes the translation first, and then the computer runs the already compiled output.

But there is a problem here too. Suppose there is an error in one of the lines of code. The compiler will not stop at that point. It will continue compiling the rest of the program. That means if your program contains faulty logic, such as an infinite loop or something that causes a memory leak, it can still end up being executed and may crash your system. You don’t get the same kind of immediate stop and feedback that you get with interpretation.

So that is one of the major drawbacks of compiled languages. They are harder to debug, and in some cases, they can crash the system. The reason is that the entire code gets compiled first, so you don’t immediately know which exact line caused the problem while the program is being prepared.

To find the issue, you usually have to run the program first, and only then you can detect where the problem actually happens. In short, interpretation makes debugging easier but execution slower. Compilation makes execution faster, but debugging harder and failures more risky.

Just-In-Time (JIT) Compilation

Now imagine if there were a way to combine both approaches, meaning fast execution like compilation and easy debugging like interpretation. That is exactly what modern JavaScript engines do using a technique called Just-In-Time compilation, or JIT compilation.

This idea was popularized in 2008 when Google introduced the V8 engine for Chrome. Instead of choosing between interpretation or compilation, V8 combined both into a single system. The result was a much more balanced execution model.

With JIT compilation, JavaScript code isn’t compiled all at once before execution. At the same time, it’s not interpreted line by line for the entire program either. Instead, the engine starts by interpreting the code so it can run immediately and remain easy to debug.

As the program runs, the engine watches which parts of the code are actually being used. When a particular function or instruction is executed, the JIT compiler steps in and compiles only that specific piece of code into machine code. That compiled version is then executed directly by the computer, which makes it much faster.

For example, when a function like instructionOne runs, the JIT compiler converts just that function into machine code and executes it. If another function is called later and contains an error, the engine can still detect that error immediately and stop execution at that exact point. This keeps the debugging experience similar to interpretation.

This approach allows JavaScript to run much faster than pure interpretation while still providing clear error messages and precise debugging. It may not be as fast as a fully compiled language in every scenario, but in real-world usage, the performance difference is usually unnoticeable.

In simple terms, JIT compilation gives JavaScript the best of both worlds. It’s fast enough to feel compiled, while still being flexible and easy to debug like an interpreted language. This is how modern JavaScript engines, including Node.js, execute code today.

With that understanding in place, we can now move on to the main topic: JavaScript Execution Context.

Introduction to JavaScript Execution Context

Many people start learning directly from the Execution Context, but I believe it's important to first understand how the compilation process works. Now that you have that foundation, when you dive into Execution Context, your brain will be able to connect both parts and visualize the complete picture of how JavaScript truly operates.

I think that Execution Context is the most important concept in JavaScript. The reason is simple: if you truly understand how it works, then advanced topics like Hoisting, Scope, Scope Chain, and Closures will become much easier to grasp.

Let’s start by thinking about how you usually write code. One common strategy is to break your code into smaller parts. These separate pieces of code can have different names – like functions, modules, or packages. But no matter what you call them, their purpose is the same: to break a complex program into smaller, more manageable chunks. This division reduces complexity and makes your code easier to read, maintain, and debug.

Before we dive into execution context itself, let’s look at a small, practical example that we’ll use throughout this section.

In this example, we’ll simulate a simple real-world flow: taking an order, processing it, and completing it. First, we’ll see everything written inside a single function. Then, we’ll refactor the same logic into multiple smaller functions.

The goal here is not performance, but structure. As you read the code below, pay attention to how breaking logic into smaller functions makes the program easier to understand – and how this directly relates to how JavaScript creates execution contexts internally.

Code Breakdown

In the animation above, the first example shows all the logic written inside a single function. The second example shows the same logic broken down into multiple smaller functions, where each function handles one specific task. At first glance, the single-function version may seem simpler because everything is written in one place. But in real applications, this approach quickly becomes hard to read, test, and maintain.

Here is the first version of the code, where all the logic lives inside a single function:

function takeOrder() {

console.log("Taking Order");

console.log("Processing Order");

console.log("Completed Order");

}

takeOrder();

In a real-world application, things aren’t that simple. Instead of just console logs, there would be complex logic, multiple algorithms, API calls, and data processing happening behind the scenes. That’s why we usually break code into smaller parts, where each part handles one specific responsibility.

Now, here is the same logic rewritten using multiple smaller functions, each responsible for a single step:

function takeOrder(callback) {

console.log("Taking Order");

callback();

}

function processOrder(callback) {

console.log("Processing Order");

callback();

}

function completeOrder() {

console.log("Completed Order");

}

takeOrder(function () {

processOrder(function () {

completeOrder();

});

});

Now, imagine if you wrote all those complex operations (like taking orders, processing them, and completing them) all inside a single file or function. That would make your code neither easy to read nor easy to maintain. It would quickly become messy and difficult to debug.

But if you break each task into smaller functions, it becomes much easier to maintain, and the overall complexity of the code decreases significantly.

In the same way, JavaScript also breaks down your code into smaller parts before interpreting it. This helps reduce the complexity of execution. Each of these smaller units is what we call an Execution Context.

What is an Execution Context?

An Execution Context is basically a small, isolated environment where a specific piece of code is interpreted and converted into machine language. So, to make its job easier, the JavaScript engine divides your code into smaller parts and executes them one by one. Each of those parts is an Execution Context.

In this section, you'll learn how Execution Contexts are actually created inside the JavaScript engine – line by line – so you can clearly visualize what happens behind the scenes when your code runs.

In the animation above, one panel shows the code being written, and the other panel shows the execution context being created step by step. Now, at this point, the panel that shows the code is completely empty.

The Global Execution Context

Even when there's no code written yet, JavaScript still creates something called a Global Execution Context right at the very beginning. Think of the Global Execution Context as a simple object – or you can visualize it as a box, a container that holds everything your program needs to start running.

At the very start, before any code is executed, this Global Execution Context is created. Inside it, you have:

the

windowobject, which you may already be familiar with,the

thiskeyword, which initially points to thewindowobjectthe Variable Object, and

the Scope Chain.

Two Phases of Execution Context

There's one more important thing to understand: the Global Execution Context actually goes through two distinct phases.

First, we have the Loading Phase (also called the Creation Phase). During this phase, your code doesn't execute yet. Next, we have the Execution Phase. During this phase, your code actually runs.

To summarize, when the Global Execution Context is first created, it contains four main components: window, this, variable object, and scope chain. And before any line of code runs, JavaScript first goes through the Loading Phase.

Understanding the Loading and Execution Phases

Now, let's assume you've written some code. It's just a short seven-line script where you have a variable named topic and a function called getTopic that simply returns that topic:

var topic = "JavaScript Execution Context";

function getTopic() {

return topic;

}

console.log(getTopic());

As you can see in the code below, when the Global Execution Context is created, it already includes window, this, variable object, and scope chain. Along with that, during the Loading Phase, any functions and variables declared in your code – like topic and getTopic – also get added to the Global Execution Context.

But here's an important point: during the Loading Phase, these variables and functions are only recognized, not yet fully executed. That means their values are temporarily set to undefined until the actual execution begins.

As I mentioned earlier, there's something inside the Global Execution Context called the Variable Object. During the Loading Phase, JavaScript allocates a specific space in memory for every variable declared in the code.

So, for example, a memory slot is created for your variable topic, and JavaScript assigns it the value undefined at this stage. Similarly, the getTopic function is also stored inside that same Variable Object. But instead of assigning it an undefined value, JavaScript stores a reference to the function – meaning the function's entire structure or body is saved somewhere in memory.

So now, through the Global Execution Context, JavaScript already knows that there's a function called getTopic defined in the program. It hasn't executed it yet, but it's aware that such a function exists and might need to be called later during execution.

The Execution Phase

Once the Creation Phase is complete, JavaScript moves on to the second phase: the Execution Phase. In this phase, the program starts running from the very beginning, line by line.

So when execution begins, it looks at the first line, var topic = "javascript execution context". Now, JavaScript already knows the variable named topic, because during the Loading Phase, it had already stored it in memory with the value undefined. When the Execution Phase starts, JavaScript simply replaces that undefined with the actual value you've assigned. This is the first time the code truly gets executed.

During the Creation Phase, JavaScript also stored the getTopic function in its memory. It knows that somewhere in this program, there's a function called getTopic. So when it reaches line 7, where the function is called, it retrieves that function reference from memory and executes it.

Hoisting Explained Through Execution Context

Now imagine you write console.log(topic) at the very top of your code – meaning you're trying to use the variable before it's even declared.

In earlier tutorials on JavaScript Hoisting, I explained this concept, but not in this much detail – and not in the context of the Execution Context.

Back then, I said that during hoisting, JavaScript conceptually moves all variable declarations to the top of the scope, though only the declarations – not the actual values. But now, through the lens of the Execution Context, you'll understand what really happens behind the scenes.

Here’s the same example:

console.log(topic);

var topic = "JavaScript Execution Context";

function getTopic() {

return topic;

}

getTopic();

As you saw above, during the Loading (Creation) Phase, JavaScript already stored the variable topic in memory and assigned it the default value undefined. It also stored the getTopic function in memory as a complete function. That’s why, when execution starts and JavaScript reaches the very first line, it can already find topic in memory, even though the assignment hasn’t happened yet.

Since the value is still the default one from the Loading Phase, the console prints undefined. Then the program continues line by line. When JavaScript reaches this line var topic = "JavaScript Execution Context", this is the moment the value actually gets assigned. In other words, the engine updates the value of topic inside the current execution context from undefined to "JavaScript Execution Context".

After this point, any code that reads topic will see the updated value. For example, if you place a console.log(topic) below the assignment, it will print the correct string, because the value is no longer undefined.

The same idea applies when getTopic() is called. JavaScript already has the function stored in memory, so it can execute it immediately when the call happens. Inside that function, it looks up topic and returns the value that is currently stored in memory. If the assignment has already run, getTopic() returns "JavaScript Execution Context".

So if you’ve watched my earlier hoisting tutorial and now you’re reading this guide, you should finally see why this behavior happens inside the JavaScript engine. Explaining hoisting as “variables being moved to the top” was a simplified way to help visualize it. The actual reason is that the variable is created in memory during the Loading Phase with a default value, and only later updated during the Execution Phase when the assignment line runs.

Summary of Global Execution Context

To summarize, the Global Execution Context is basically a JavaScript object. At the very beginning, it contains the window object (if you're in a browser environment), the global object (if it's Node.js), a this object that points to that same window or global, all variables declared in your code stored inside something called the variable object, and any functions you define (that are also stored there, but only as references – meaning JavaScript just keeps a pointer to their full body in memory).

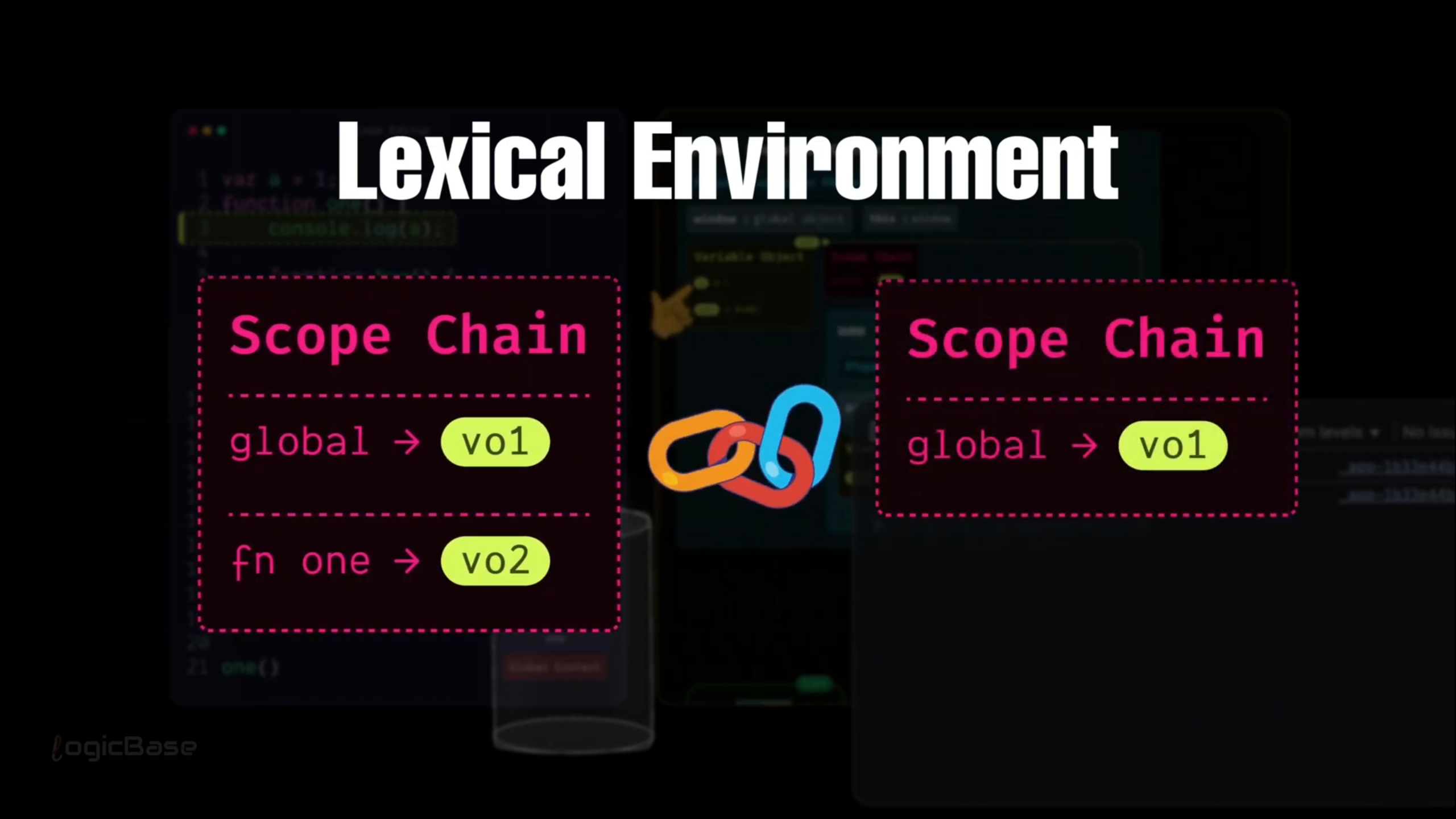

It also keeps something called a Scope Chain. As you may know, JavaScript uses lexical scoping – meaning each function knows exactly where it was written and can access variables from its outer scopes. So, JavaScript maintains all these scopes together inside the Scope Chain.

Function Execution Context

By this point, you should understood how the Global Execution Context works. The good news is that after this, you only need to understand one more type of Execution Context: the Function Execution Context. The interesting thing is, it's almost identical to the Global Execution Context. The only difference is that it's created every time a function is called.

Comparing Global and Function Execution Context

Let's quickly recall what happened inside the Global Execution Context. It created a global object, created a this object, allocated memory for variables and functions, and initially assigned all variables the value undefined.

Now, if you think carefully, which of these four steps do you think won't be necessary when a function gets executed? Exactly: the Global Object shouldn't get created again inside a Function Execution Context. Because the entire program already has one Global Object that was created earlier, and all functions can access it when needed.

So, instead of creating a new Global Object, something new happens inside the Function Execution Context: it creates an "arguments object". This object holds all the parameters passed to that function. That means whenever you define a function in JavaScript and it has parameters, JavaScript automatically creates an object called arguments inside that function's Execution Context to store those values. If you write console.log(arguments) inside the function body, you'll see all the passed parameters neatly stored as key-value pairs within that arguments object.

So the only structural difference between the Function Execution Context and the Global Execution Context is this: Global Execution Context contains a Global Object, and Function Execution Context contains an Arguments Object. Everything else remains exactly the same.

Simply put, think of the Global Execution Context as an entire world. Whenever you call a function, a new world is created inside that global world, following the same structure and behavior.

How Function Execution Context Works

When a function is called, JavaScript creates a completely separate Execution Context for it. Inside that context, it builds an arguments object to hold all the parameters, creates a this object as usual, and allocates memory for all the variables and inner functions defined inside that function.

That means hoisting also applies inside functions. During the Creation Phase, JavaScript will assign undefined to all variables within that function, and that's exactly why hoisting happens there, too.

Understanding the Execution Stack (Call Stack)

Now, remember how I mentioned earlier that in JavaScript, one function can contain another function? This naturally means that multiple Execution Contexts can exist at the same time.

Here’s a simple example to visualize that idea:

function one() {

function two() {

function three() {

// some logic here

}

three();

}

two();

}

one();

In this example, functions are called one after another, but not all at once. Each time a function is called, JavaScript creates a new Function Execution Context for it.

This is where the Call Stack comes in.

The Global Execution Context is created first and stays at the bottom. When one() is called, its execution context is created and placed on top of the stack. Inside one(), when two() is called, a new execution context for two() is added on top of one(). Then, when three() is called, its execution context is added on top of two().

At this point, the call stack looks something like this (from bottom to top):

Global Execution Context

one()Execution Contexttwo()Execution Contextthree()Execution Context

Once three() finishes executing, its execution context is removed from the stack. Control returns to two(). When two() finishes, its execution context is removed, and control returns to one(). Finally, when one() finishes, its execution context is also removed, leaving only the Global Execution Context.

Because JavaScript is a single-threaded language, all of this happens on one main thread. That same thread is responsible for creating execution contexts, placing them on the call stack, and removing them once their work is done. This stacking and unstacking of execution contexts is exactly what we refer to as the Execution Stack, or more commonly, the Call Stack.

How the Call Stack Works

JavaScript actually stores these contexts one on top of another, just like a stack. And this stacking structure is called the Call Stack.

At the very beginning, JavaScript places the Global Execution Context at the bottom of the stack. Then, whenever a function is called, a new Function Execution Context is created and pushed on top of it. If that function calls another function inside it, another context is stacked above that, and so on.

In this way, JavaScript keeps adding and removing Execution Contexts in a stacked order as the program runs.

So now you have a complete picture of what an Execution Context really is, and its types:

The Global Execution Context

The Function Execution Context

Deep Dive – Multiple Functions and Nested Execution

So far, we’ve only seen how the Execution Context works in the Global Scope, or when a function is called directly from the Global Scope. But what if you have multiple functions? Or if one function contains another function – in other words, nested functions? How does the Execution Context behave then?

Every time JavaScript creates an Execution Context, it needs to keep track of it somewhere in memory. There has to be some logic to determine which context should run first, and which one should execute next. To manage all of that, JavaScript needs to maintain a specific data structure, right?

And that data structure is called the Execution Stack. It's actually based on a Stack data structure. Think of it like stacking books on a table: you place one book on top of another. Similarly, JavaScript stacks each Execution Context on top of the previous one inside the Execution Stack.

Now, a stack has one special property: the last item that goes in is always the first one to come out. In short, it follows the LIFO rule, or Last In, First Out.

A Practical Example with Code

Alright, let's connect this idea with your code. You know that whenever you run a JavaScript program, the Global Execution Context is created first. Whether your file contains code or not, this Global Context will always be created automatically. And once it's created, JavaScript places this Global Execution Context at the very bottom of the Execution Stack. That's where everything begins.

Let’s look at an example:

var a = 1;

function one() {

console.log(a);

function two() {

console.log(b);

var b = 2;

function three(d) {

console.log(c + d);

let c = 3;

}

three(4);

}

two();

}

one();

In the above code, you have three things: a variable declared with var a, a function called one with its definition, and finally a call or invocation of that function. These three (the variable a, the function one, and its invocation) all exist in the Global Scope, or the root level of the program.

Inside the body of the one function, there's another nested function called two, and inside two, there's yet another function called three. These nested functions are not part of the Global Scope – rather, they belong to their respective inner scopes.

So, during the Creation Phase, JavaScript allocates memory for the variable a (initially setting it to undefined) and stores a reference to the function one in the global memory/variable environment so it can be invoked later during execution.

Since there's nothing else in the Global Scope, JavaScript then moves on to the Execution Phase. In this phase, execution starts line by line. First, it updates the value of a from undefined to 1. Then it moves to the next line, where it finds the function definition of one. Since that function's reference is already stored in the Scope Chain, JavaScript skips over the function body for now and continues to the next line – the point where one() is actually invoked.

Creating the First Function Execution Context

As soon as the one function is invoked, JavaScript creates a brand-new Function Execution Context inside the Execution Stack, placed right above the Global Execution Context. When this new context for one is created, it first enters its Loading Phase. Since the one function doesn't take any arguments, the arguments object inside this Execution Context will remain empty.

Then comes the this reference, which points to the global object – in this case, the window object. After that, you have the Scope Chain and the Variable Object. Inside the Variable Object, there's only the two function. Why? Because inside the body of one, there are no local variables declared – only a console.log statement that tries to print a.

But since the variable a is not defined inside one, it doesn't appear in this context's Variable Object. Instead, JavaScript will later look for it in the outer scope using the Scope Chain. But the one function body does contain another function declaration: the two function. So, during the Loading Phase, JavaScript stores that two function inside the Variable Object, just like it stored the function definitions earlier in the Global Execution Context. It follows the exact same process, only this time, it's happening inside the function's own scope.

Alright, now let's check if there's anything else inside the body of the one function that needs to be added to its Variable Object. The answer is no – there's nothing else.

So next, JavaScript moves to the Execution Phase, and just like in the Global Execution Context, it starts executing line by line. The first line inside the one function is console.log(a). At this point, JavaScript checks whether the variable a exists inside the Variable Object of the current Execution Context. It looks and finds nothing.

Since the variable a isn't declared inside the one function, JavaScript moves to the next step – it follows the Scope Chain to look into its parent scope. Now, what's inside the parent scope? Yes: the variable a is there, defined in the Global Execution Context. So JavaScript retrieves that value and prints it in the console.

Understanding the Scope Chain

It's important to clearly understand one thing here: the Scope Chain is essentially a Lexical Environment. This means that every scope is connected to its parent scope in a linked structure. The term "chain" is used because each scope holds a reference to its parent or ancestor scopes, forming an actual chain-like connection.

That's why, when JavaScript couldn't find the variable a in the one function's own Variable Object, it followed that chain upward (to its parent or ancestor scopes) and successfully found a in the Global Scope.

Creating Nested Function Execution Contexts

After printing the value of a, the program moves to the next line. There it finds the body of the two function.

But at this stage, JavaScript doesn't need to do anything with it. This is because during the Loading Phase, the reference to two has already been stored in memory. So it skips over the function body and moves to the next line, where it sees that two() is being invoked.

Since the two function is now being called, JavaScript creates a brand-new Function Execution Context for it, and places it on top of the Execution Stack. Just like before, when this new two Execution Context is created, it first goes through its Loading Phase. During this phase, it populates its Scope Chain, meaning it links itself with the Variable Objects of its parent or ancestor scopes.

Inside the body of two, there's a variable named b, so in this new context's Variable Object, JavaScript stores b with the initial value undefined. Then it finds another function definition, three. So, just like before, JavaScript stores the reference to the three function inside the Variable Object of two.

Then in the next line, the program moves to where the function three is called. Since it's still in the loading phase, there's nothing to execute yet. That part is done, so now it enters the execution phase and starts running each line one by one.

Inside the function three, what's the first line? It's a console log of the variable b. But that variable hasn't been initialized yet. In this context, its value is still undefined. So, when the program runs that line, it prints undefined. Now you can clearly see why during hoisting, variables often print undefined.

Once you understand how the Execution Context works, many other tricky behaviors of JavaScript start to make sense. So pay close attention and try to grasp these terms deeply.

Alright, after that, in the next line, the variable's value is being assigned. So, the value of b changes from undefined to 2. Then in the following line, you see the definition of the three function. The Execution Context doesn't need to do anything here, so it simply skips over this line. The next line shows that the three function is being invoked – and not just that, it's being called with an argument, 4.

Creating a Deeply Nested Function Execution Context

Since the three function has been invoked, a brand-new Execution Context is created inside the execution stack. During the Loading Phase of the three Execution Context, you can already see that there's a value inside the arguments. At index 0, it's 4. That's because when the function was called, the value 4 was passed in.

And here's something interesting: look at how you named the parameter inside the three function. It's called d, right? So, during the Loading Phase itself, a variable named d appears inside the context, and it's already assigned the value 4. Then it moves to the next line. There's a console.log statement, but nothing special happens there yet. After that, you have let c = 3; – and this is where things get a bit different.

Understanding var, let, and const

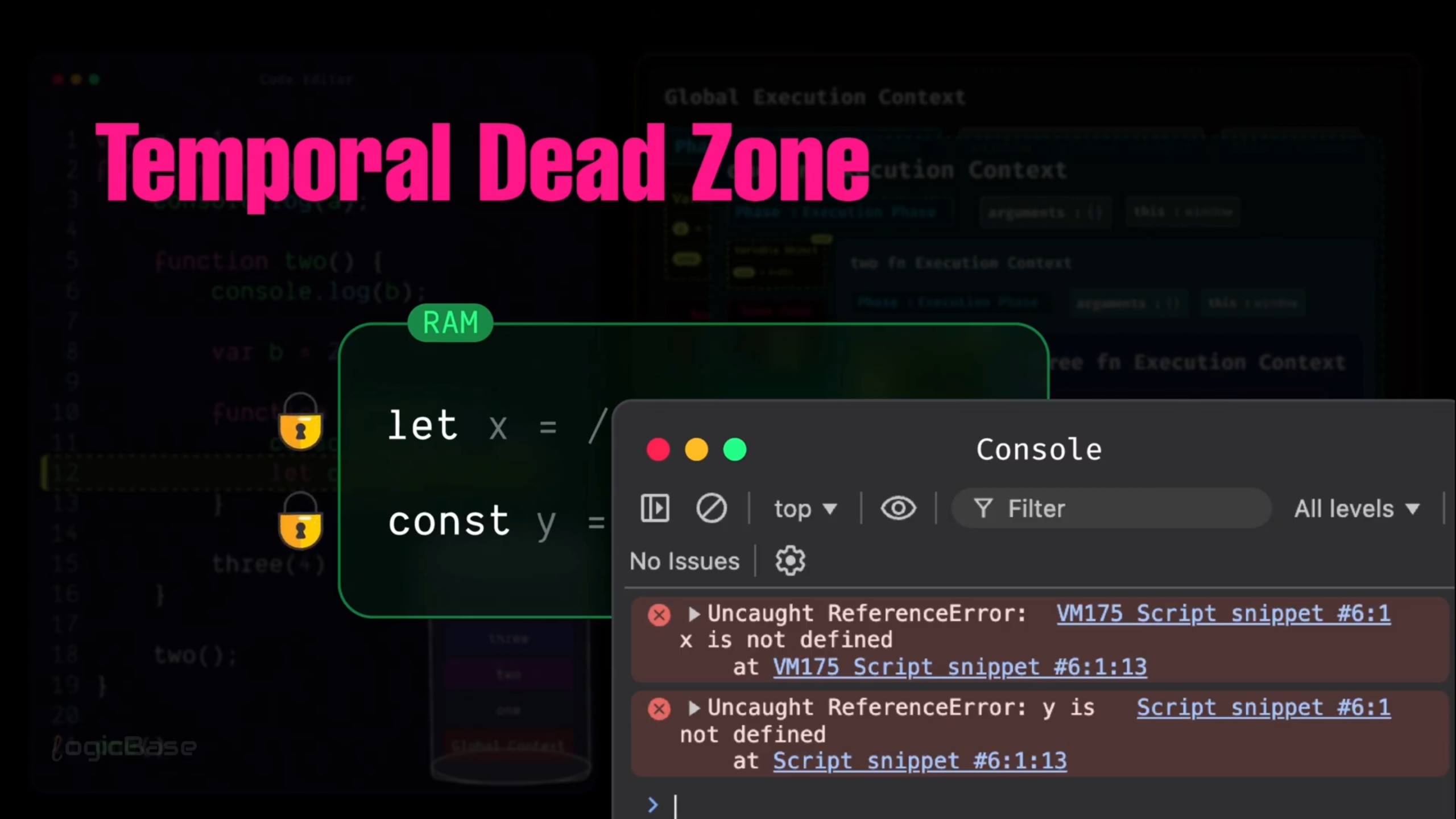

You see, although var, let, and const are all used to declare variables, their behaviors are not the same. For var, during the Loading Phase, JavaScript automatically allocates memory and sets its value to undefined. But for let and const, JavaScript still allocates memory during the Loading Phase.

The difference is, they remain inside what's called the Temporal Dead Zone (TDZ) until the actual line of code where they are declared is reached. That means, even though they exist inside the Execution Context, they can't be accessed through the Variable Object yet.

So you might be wondering, what is the Temporal Dead Zone? It's the period between a variable being created in memory and being initialized with a value. During this time, the variable technically exists, but since no value has been assigned, JavaScript keeps it temporarily inaccessible. If you try to access that variable during the TDZ, you'll immediately get a ReferenceError.

In simple terms, the program knows that the variable exists, but it's not ready to be used yet. And until the code execution reaches that specific declaration line, you won't be able to access it from the Variable Object either. You can think of it like an iPhone's locked screen: the phone is there, but until you enter the PIN and unlock it, you can't do anything with it.

Why the Difference Between var and let/const?

Now, many people wonder, doesn't the same thing happen with var? Why does JavaScript assign undefined to variables declared with var, but keeps let and const inside the TDZ instead of doing the same?

Excellent question! The main reason is that var comes from the older versions of JavaScript – specifically ES5 and earlier – where there was no concept of safety checks or the Temporal Dead Zone. Back then, JavaScript didn't want the program to crash if a variable was accessed before initialization. So, to avoid breaking the program, it would automatically assign undefined as a fallback value.

But let and const were introduced in ES6, where the goal was to make the language safer and more predictable. If JavaScript had assigned undefined to them as well, it would have created the illusion that the variable was properly initialized, even though it wasn't. So, JavaScript intentionally blocks access to those variables during that time to signal to developers, "The variable exists, but it's not ready to be used yet." This is a key difference that makes your code safer and helps catch bugs earlier in the development process.

Continuing with Code Execution

Now let's get back to the flow. At this point, inside the three function, there's nothing else left to load, so it moves to the Execution Phase.

In the first line, you have a console log printing c + d. You already know that the value of d is 4, but the variable c is still inside the Temporal Dead Zone – meaning it can't be accessed yet. So this line will throw a ReferenceError, because the program can't reference c from memory at that point. But if you had written the code the other way around (first declaring let c = 3, and then logging it in the next line), the behavior would have been completely different.

In that case, during the creation phase, c would still start in the Dead Zone, but by the time the execution reached that line, its value would already be assigned. Then, when the console log ran, both c and d would be accessible, and their values would print correctly. I hope that’s clear now.

So, you can now see how JavaScript actually works behind the scenes. You've also learned how hoisting truly operates at a machine level through the concept of the Execution Context.

The Function Returns and Exits the Stack

Alright, now let's move forward. Inside the three function, once the console.log runs successfully, it will print 7. After that, is there anything else left in the function? No, there isn't. Since there are no more lines to execute, the work of the three function is complete. Whenever a function finishes its job, it immediately gets popped out from the execution stack. That means, since the three function has finished executing, it will be removed from the stack following the LIFO (Last In, First Out) rule.

Now, what’s at the top of the stack? The two function. If you check the body of two, do you see any remaining lines to execute? No, it's done too. So, two will also exit from the execution stack. Finally, since there's nothing left to run in one, that function will also pop out, leaving the execution stack completely empty.

Since there are no more functions left to execute, the Global Execution Context will also exit from the execution stack. But if there had been more code to run in the global scope (for example, another function call right after one()) then the Global Execution Context wouldn't have been removed yet. Instead, it would have continued executing the next function just like before.

Understanding Scope Through Execution Context

Now, let's move on to another important concept: Scope. We’ve discussed Scope a bit already, but this time, you'll understand how Scope works in relation to the Execution Context.

Take a look at this simple example:

function hello() {

var message = "hello world";

}

hello();

console.log(message);

Here, you have a function called hello. Inside it, there's a variable named message declared with var, which holds a certain value. Outside the function – that is, in the global scope – you're calling or invoking the hello function, and in the next line, you're trying to print the message variable using console.log. It's a very simple setup.

How Scope Works

So, based on everything you've learned so far, what will happen if you run this program? First, the Global Execution Context will go through its Creation Phase. During this phase, it will find a function named hello, and store its reference inside the Variable Object.

Once that's done, there's nothing else left for the Creation Phase. Perfect. Now the Execution Phase begins. The first line is the definition of the hello function. Since you're in the Execution Phase, there's nothing to execute here – the function's reference is already stored in memory. So the program moves on to the next statement, where the hello function is invoked.

As soon as that happens, a new Execution Context for the hello function is created. Inside the Creation Phase of the hello function's Execution Context, the variable message is placed inside the Variable Object with the value undefined. Once the creation phase is complete, the program moves to the Execution Phase, where the variable message gets its actual assigned value instead of undefined. So, in the execution phase, the value of the message variable becomes "hello world".

After that, does the hello function have anything else to do? No, it doesn't. So, the hello function's Execution Context will now be popped off or destroyed. That means the program returns to the Global Execution Context.

The Problem with Accessing Inner Scope Variables

Now what happens next? After the hello function is invoked, the next line is console.log(message). So, the program will now try to print message.

But wait – is the message variable declared inside the Global Execution Context's Variable Object? No, it isn't. That variable was created inside the Function Execution Context, and when that function finished executing, its Execution Context – along with its Scope Chain and Variable Object – was completely removed from memory. That's why, when the console tries to access message, JavaScript throws a ReferenceError.

Connecting to Scope Understanding

Can you relate this now? If you’ve seen my earlier tutorials on Scope, you might remember this concept: a child can always access or inherit things from its parent, but a parent can never access what belongs to the child.

In those tutorials, it was just an example. But now, you can actually visualize how the program manages all of this behind the scenes. That means, while understanding Execution Context, you've rediscovered the concept of Scope in a much clearer, more practical way.

Understanding Closures Through Execution Context

Now, let's move on to another very important topic: Closures. Just like you visualized Execution Context earlier, you'll now see how a Closure is created and how it works step by step.

Here's an example:

var sum = 0;

function doSum(a) {

return function (b) {

return a + b;

};

}

var temp = doSum(2);

sum = sum + temp(8);

Step-by-Step Breakdown of a Closure

First, the program creates the Global Execution Context. You're now in the Creation Phase. During this phase, the program scans through the code and finds a variable named sum and a function named doSum. So, memory is allocated for sum, and its initial value is set to undefined. The entire function definition of doSum is stored in memory as a reference.

Once the Creation Phase is complete, the Execution Phase begins. In the Execution Phase, the first line sets sum = 0. Next, the program skips over the doSum function since it's only a definition. Then it moves to the line var temp = doSum(2). Here, the function is being called, so a brand-new Function Execution Context is created for doSum.

Now, the Creation Phase of that Function Execution Context begins. The parameter a receives the value 2, so in memory you have a = 2. Inside the function, there's an anonymous function being returned, and that function's reference also gets stored in memory.

Once the Creation Phase is done, the Execution Phase starts. During this Execution Phase, the doSum function doesn't perform any calculation. Instead, it simply returns that anonymous function. When that happens, the doSum Execution Context is popped off the stack. But something very important also occurs at that exact moment: a Closure is created.

Why Does a Closure Form?

Why does that happen?

Because when the anonymous function is returned, it still remembers the data from its outer scope – in this case, a = 2. Even though the doSum function itself gets destroyed, its lexical environment doesn't disappear completely. JavaScript realizes that this inner function might be called again later, and when that happens, it will need access to those outer variables. So, it preserves that environment in a separate structure called the Closure Scope.

Using the Closure

Next, the code moves to the line sum = sum + temp(8). Here, the function is called again, meaning temp(8) is invoked. This creates a new Execution Context for the anonymous function. During its Creation Phase, the parameter b is assigned the value 8. When the Execution Phase begins, the function executes return a + b.

Now, since a doesn't exist in the current scope, JavaScript follows the scope chain and looks into the outer scope – which is the Closure Scope. There it finds a = 2, performs the calculation 2 + 8 = 10, and returns the result 10. At that point, the temp function's Execution Context completes its job and gets popped off from the stack.

Summary of Closures

So, in the line sum = sum + temp(8), the value of sum was initially 0. That means it becomes sum = 0 + 10. Now where did that 10 come from? It came from the temp function's Execution Context.

Now you can clearly see how a Closure actually works. A Closure is basically a mechanism that keeps a function connected to its outer environment, even after the outer function has been destroyed**.** This is one of JavaScript's most magical yet completely logical behaviors – and it all originates from the concept of the Execution Context itself.

Bringing It All Together

So, everything you've seen so far – this is what JavaScript's Execution Context truly is. By understanding just this one topic, you've been able to uncover how JavaScript actually works behind the scenes.

You discovered how scopes are formed and how confusing topics like Closures and Hoisting really operate logically within the language. All this time, you may have just been repeating what you heard – "Hoisting means variables are lifted to the top" and "Closure means a function stays connected to its outer environment". But after reading this guide, you should now have a clear, inside-out understanding of how and why JavaScript behaves this way.

Summary

Execution Context is one of the most fundamental concepts in JavaScript that explains how the JavaScript engine actually runs your code behind the scenes.

What You’ve Learned

How JavaScript Engines Work - The guide started out by explaining that JavaScript engines (like V8 in Chrome and Node.js) convert your human-readable code into machine language that computers can understand. It covered the evolution from simple interpretation to modern Just-In-Time (JIT) compilation, which combines the ease of debugging with fast execution.

What an Execution Context really is - An Execution Context is a small, isolated environment where JavaScript interprets and executes specific pieces of your code. Think of it as a container that holds everything needed to run a particular section of code.

Two Types of Execution Contexts -

Global Execution Context – Created automatically when your program starts, containing the global object (

windowin browsers,globalin Node.js), thethiskeyword, a variable object, and the scope chainFunction Execution Context – Created every time a function is called, similar to the Global Context but with an arguments object instead of a global object

Two Phases of Execution – Every Execution Context goes through two phases -

Creation Phase (Loading Phase) - JavaScript scans your code and allocates memory for variables (setting them to

undefined) and stores function references, but doesn't execute anything yetExecution Phase - Your code runs line by line, and variables get their actual assigned values

The Call Stack - JavaScript manages multiple Execution Contexts using a stack data structure called the Call Stack or Execution Stack. It follows the LIFO (Last In, First Out) rule, meaning the last function added is the first one removed when it finishes executing.

Hoisting Explained - Through Execution Context, you should now truly understand why hoisting happens. Variables declared with

varare set toundefinedduring the Creation Phase, which is why you can reference them before their declaration (they returnundefined). Variables declared withletandconstremain in the Temporal Dead Zone (TDZ) until the actual declaration line is reached, which prevents access errors.Understanding Scope and Scope Chain - Scope is managed through the Scope Chain, a linked structure that connects each scope to its parent scope. This is why inner functions can access outer variables, but outer functions cannot access variables declared inside inner functions.

Closures Demystified - Closures are created when a function is returned from another function and retains access to its outer scope's variables, even after the outer function has been destroyed. JavaScript preserves the lexical environment in something called the Closure Scope.

var vs. let vs. const - The guide clarified the key difference –

vargets assignedundefinedduring the Creation Phase (legacy behavior from ES5), whileletandconstremain in the Temporal Dead Zone until their declaration is reached, making them safer and more predictable.

Final Words

I hope this comprehensive guide has helped you understand Execution Context and all the concepts connected to it. By mastering this fundamental concept, you now have the foundation to understand nearly every advanced JavaScript topic that comes your way.

When you encounter tricky JavaScript behaviors in the future, you can refer back to Execution Context to understand the "why" behind them. This will make you a much more effective and confident JavaScript developer.

Keep practicing, keep experimenting, and keep deepening your understanding of how JavaScript truly works at the engine level. Your journey to becoming a JavaScript expert has just gotten much clearer!

If you found the information here valuable, feel free to share it with others who might benefit from it. I’d really appreciate your thoughts – mention me on X @sumit_analyzen or on Facebook @sumit.analyzen, watch my coding tutorials, or simply connect with me on LinkedIn. You can also checkout my official website sumitsaha.me for details about me.