by Sachin Malhotra

How to solve the Baby Lizards Problem — a fun twist on the N-Queens problem

This problem statement was an assignment as a part of my coursework for the Masters program at USC. I had loads of fun while solving it and I decided to share my learnings with the community.

Let’s start with the problem statement.

The Problem

You are a zookeeper in the reptile house. One of your rare lizards has just had several babies. Your job is to find a place to put each baby lizard in a nursery. However, there is a catch: the baby lizards have very long tongues.

A baby lizard can shoot out its tongue and eat any other baby lizard before you have time to save it. As such, you want to make sure that no baby lizard can eat another baby lizard in the nursery (burp).

For each baby lizard, you can place them in one spot on a grid. From there, they can shoot out their tongue up, down, left, right and diagonally as well. Their tongues are very long and can reach to the edge of the nursery from any location.

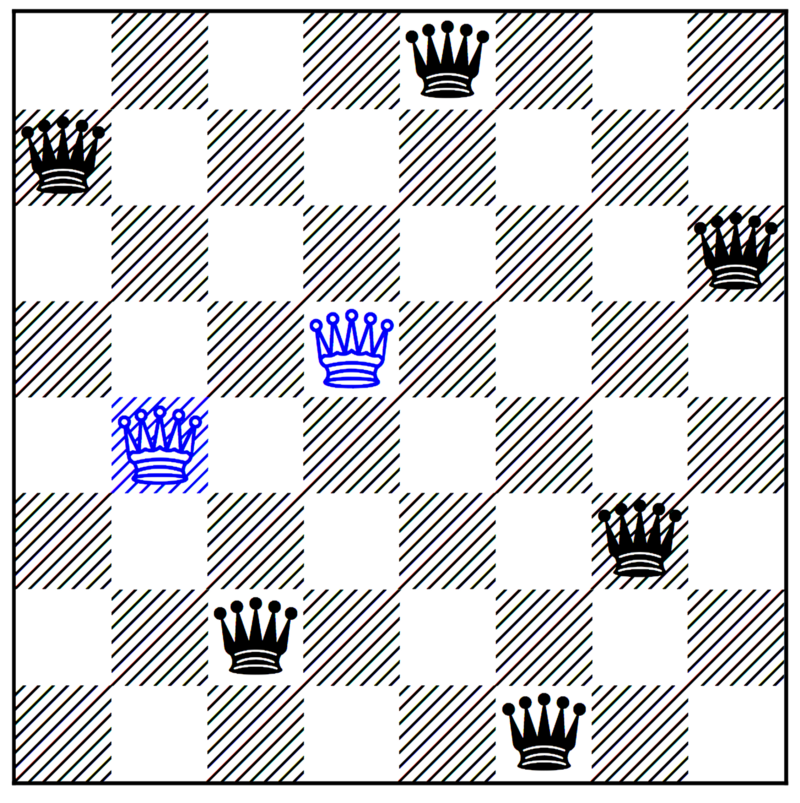

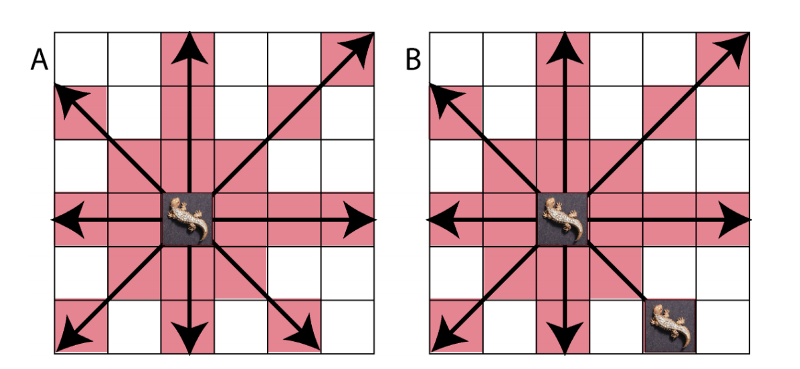

Figure 1 shows in what ways a baby lizard can eat another.

In addition to baby lizards, your nursery may have some trees planted in it. Your lizards cannot shoot their tongues through the trees nor can you move a lizard into the same place as a tree.

As such, a tree will block any lizard from eating another lizard if it is in the path. Additionally, the tree will block you from moving the lizard to that location.

Figure 2 shows some different valid arrangements of lizards:

another. (A) with no trees, no lizard is in a position to eat another lizard. (B) Two trees are

introduced such that the lizard in the last column cannot eat the lizard in the second or fourth

column.

Given an arrangement of trees, we need to output a new arrangement of lizards such that no baby lizard can eat another one. You cannot move any of the trees.

You can find the entire code for this here.

Similarity to N-Queens

This problem is very similar to the classic N-Queens Problem. Let’s recap some of the constraints in the N-Queens problem.

- There can be only one queen per row and column.

- There can be only one queen per diagonal and anti-diagonal.

- Considering the above 2 constraints, we cannot place more queens than the number of rows or number of columns.

Now, we add in a little twist which says that we have trees at certain location in the nursery (read chess board), and the queens (lizards) on either side of a tree cannot attack each other. This changes things big time.

- Now, we can have multiple lizards per row, per column.

- Similarly, we can have multiple lizards in a single diagonal or anti-diagonal.

- We can place more number of lizards than the number of rows or columns.

Although the problem looks very similar to the standard puzzle of placing N queens on an N*N board, the solution and the complexity turn out to be very different altogether.

None of the optimized versions of N-Queens fit in directly for this problem because a lot of the optimizations rely on the simple fact that a solution to the N-Queens problems can be represented as a permutation of column subscripts, simply because we have only one lizard per row, column, diagonal and anti-diagonal. We break this assumption, and the optimizations fall apart.

So here in this post, we will discuss a highly optimized backtracking based solution.

Backtracking++

The backtracking solution for this problem works in a similar manner to the backtracking solution for the standard N-Queens problem.

The solution for this problem is based on the following idea.

Given a cell [i, j], we can either place a lizard, or not place a lizard. Any one of our choices can lead to a solution. So we try both.

The biggest invariant in this algorithm is that we always move from left to right across the board.

Suppose there is a tree at location [3,4]. Its masking effect (if any) would only be visible once we cross the cell [3,4] in our recursion and move forward. Not before that.

Before we get to the actual pseudocode for the problem, there are some other components of the algorithm that I would like to explain. This would make the understanding of the pseudocode much simpler.

The Safety Check and the O(1) conundrum

If you’ve taken a look at my previous article that discusses different algorithmic solutions to the N-Queens puzzle, you might understand what the issue really is.

We get almost 5X speed improvement on a 14 * 14 chessboard where we have to place 14 queens, after converting the safety check function to O(1) from O(N). So it was worth spending time to figure out an algorithm that would tell us in constant time if it is safe to place a queen on a given cell [i, j].

For reference, let’s look at how we did it back in the normal N-Queens.

We made use of some additional data structures to tell us if a queen had been placed in a certain diagonal, anti-diagonal, row or column in O(1) time and using these we could tell if it was safe to place a queen on a given cell [i, j].

However, if you’ve read through the problem statement carefully, we can now have trees in some locations on the board and if there is a tree between the current cell and an attacker lizard (it can be on a row, column, or any of the two diagonals), then it is in fact safe to place a lizard on the current cell. This is because the tree masks the attack, making the cell safe for a new lizard.

This changes things, a lot ?.

Let’s start with what data structures we need for the implementation.

The Data Structures Used

Let’s go over them one by one.

tree_locations— this is just a dictionary that tells us if a given cell [i, j] contains a tree. This is populated right at the start of our solver.- The four data structures rows, columns, diagonals and anti-diagonals are used to simply tell us if there is a lizard in the respective

r, c, r — c, r + crespectively. For this problem however, they represent integer values rather than boolean.

These four data structures store either 1 or -1 depending upon if we are placing a lizard at a current cell [i, j] or we are encountering a tree at a given cell [i, j].

So the recursion proceeds from one cell to another and can either encounter a tree at a given cell [i, j] or it can encounter an empty cell in which case we have to call theis_cell_safefunction to verify if we can place a lizard.

I will come to how the values are updated in these four data structures namelyrows,columns,diagonalsandanti-diagonalslater on. is_there_queen_in_this_column— this is a dictionary that simply stores the number of lizards that we placed in a given column. This is used as a part of a pruning heuristic employed to reduce the size of the search space.next_position_same_column— this tells us for every [i, j] what is the next spot in the same column where we could try and place a new lizard. In the normal N-Queens problem, we can only place a single queen in a column, but in this case we can have multiple queens (lizards).

So, after placing a lizard at cell [i, j], we need the location of the first tree in the same column and say that is [k, j]. The next available location for placing a lizard in that column would then be [k+1, j]. This array is used as a part of this optimization.- Finally,

is_there_a_tree_aheadis a dictionary which tells us if there is a tree somewhere in the board after this column (including this column as well). This is also populated once as a part of the initial preprocessing. This is also used as a part of the pruning heuristic referred to above while describingis_there_queen_in_this_column.

The Preprocess function

The preprocess function is called initially before our algorithm starts execution and all it does is fills up some of the data structures discussed above.

- The

trees_populatorfunction is pretty straightforward. It fills up the dictionariestree_locationsandis_there_a_tree_ahead. - The function

find_next_largestconsiders each column as consisting of 0s and 2s where a 0 represents an empty cell and a 2 represents a tree. For every cell, it finds out the next largest element or in other words, the nearest tree to that location in that column. We call thefind_next_largestfunction for every column on the board.

For a better understanding of this algorithm, refer to this overview.

is_cell_safe Function

A positive value in any of the dictionaries row, column, diagonal, anti-diagonal means there is a lizard that is would potentially attack another lizard that we’re trying to place at [row, column].

This function looks very similar to the one we used for the normal N-Queens. The important part is how we update the values in these data structures.

Mark Visited, Unmark Visited and Hash Util

The function hash_util is a common function used to update the values for all the four data structures (namely rows, columns, diagonals and anti-diagonals).

This function is called both, when we are marking a lizard or a tree, or, when we are unmarking either of them. The marking and unmarking are simply processing before a recursive call and undoing whatever we processed, after the recursive call is over.

Remember the invariant discussed in this problem: we move from left to right across the board. Once we have encountered a tree at a certain location (i, j) during the recursion, it would be protecting lizards from each other for all the cells [i+1, j] and all columns k > j.

The result variable is very important here. For example, we encountered a tree at say [3,0] and there was a lizard at [1,0]. Now moving onwards, this tree is masking the effect of the lizard at [1,0] — at least for this column — and we need to bring this effect into consideration somewhere.

So, in this case:

is_marking=True,is_tree=True,dictionary=column,dictionary[col]> 0 (We store 1 whenever we place a lizard in that column). This is because we have already placed a lizard in the column 0 (at 1,0) and there was no tree discovered earlier that would hide the lizard’s effect for cell [3,0] in our example.value_to_add= -1 (For a tree it’s -1, for a lizard it’s 1)

So now, dictionary[col] = -1 and we return 1 as the result meaning that encountering a tree in the given (row, column) did in fact have some masking effect. We need to record this masking effect because this would be used at the time of undoing after recursion.

Now consider two other functions that form the main component of the algorithm.

Mark Visited

We call this function in two cases. One is when we encounter a tree, and one is when we want to place a lizard. So, accordingly we have used a boolean variable to tell us why this function has been called.

In the case of a tree, we set the value to -1, otherwise it’s +1. Then, we update the four data structures. The logic is the same for all four of them. It’s just the key that changes for each one.

Remember, row — col is used to uniquely identify a diagonal and row + colis used to uniquely identify an anti-diagonal.

Also note that we store the quadruple of return values for the four data structures in did_tree_affect dictionary. This let’s us know if encountering a tree at the location (row, col) had any effect at all i.e. masking. This data is used during the undo operation.

Unmark Visited

We know that a positive value in any of the four dictionaries means that the given cell is not safe to place a lizard.

The undo operation is pretty simple for a lizard. If we are calling unmark_visited function for a lizard, it means the cell was safe enough before we placed a lizard there, so we just put a value of -1 in all the four dictionaries. (Remember, a positive value in either of rows, columns, diagonals or antidiagonals would break the is_cell_safe function for that cell)

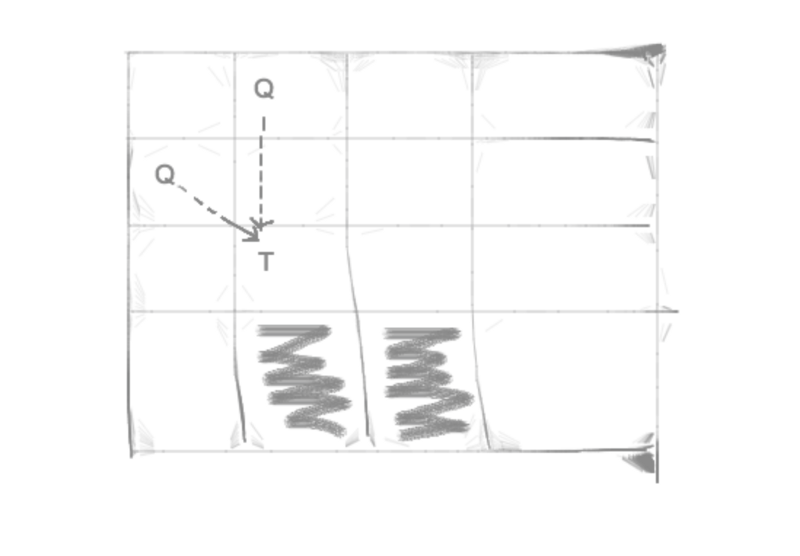

In case the function unmark_visited was called for a tree, we retrieve values from did_tree_affect for the given [row, col] and use these values to revert the dictionaries. The sense in this is that suppose that we encountered a tree at given [row, col] and it masked the lizard’s effect for the diagonal and the column moving forward. See the following figure:

When we have to revert seeing the tree in the recursion, we basically have to revert it’s masking effect. That is what the did_tree_affect dictionary is used for.

Now that we have all our dictionaries in place, we can finally look at the actual DFS function that does all our heavy lifting for finding a solution.

Backtracking Solver

The code is seemingly complicated and the post would get extremely long if I started explaining it in detail. I might be able to clarify the doubts in the comments section. For now, I’ll write a detailed version of the pseudocode for completion.

1. Start at the cell (0, 0)2. For a given cell (i, j) a. If all the lizards have been placed, print the solution and return True.b. Check if the current cell has a tree. b1. Call mark_visited function to update the 4 dictionaries with possible masking effects due to this tree.c. If the current cell isn't a tree and a lizard can be placed c1. Call mark visited for [i, j] as a lizard. c2. Add [i, j] to the solution set. c3. Increment column j as containing one more lizard. c4. Find the next row number to recurse on in the column j. If there is such a row number say r, then recurse on [r, j]. Else recurse on [0, j+1] c5. Unmark the current cell. Call function unmark_visited for [i, j] c6. Decrement column j as it contains one less lizard now.d. We may want to have a branch in our recursive solution where we did not place a lizard at [i, j] and simply moved forward. OR, we couldn't place a lizard at [i, j] and we now have to move forward. d1. if [i + 1] < n, recurse on [i+1, j] d2. else [PRUNING HEURISTIC] d2.1 check if * we did not place any lizard in the current col. * there is no tree in the current col and ahead. * number of lizards left to be placed are more than the number of columns left. * If yes to all 3, then BACKTRACK. d2.2 Else, recurse on [0, j+1]e. If the current cell was in-fact a tree, then call unmark_visited to undo its effects.That is the most apt pseudocode that I could come up with for the DFS based solver. This is exactly how the function dfs is structured.

With this logic, the largest test-case that I was able to solve was to place 97,000 lizards on a 1000 * 1000 board. It took around 2 seconds to run.

Now I’m telling you, that this might sound like a huge feat, but it isn’t actually. This was pretty easy for the algorithm. Question for you guys is to figure out the why behind this ?. Let me know in the comment section !

Also, if you do come up with some other simpler approach to solve the problem, I would love to discuss that as well. Let me know in the comment section itself.

Hope you liked the article and enjoyed as much I did while solving this problem. If you liked this post, do spread the love (❤) as much as possible. Cheers!