By Stanley Nguyen

Logging is universally present in software projects and has many different forms, requirements, and flavors.

Logging is everywhere, from small 1-person-startups to large enterprises. Even a simple algorithmic programming question involves some logging along the way.

We rely so much on logging to develop, maintain, and keep our programs up and running. However, not much attention has been paid to how to design logging within our systems.

Often times, logging is treated as a second thought – it's only sprinkled into source code upon implementation like some magic powder that helps lighten the day-to-day operational abyss in our systems.

Are we all log baes?

Are we all log baes?

Just like how any piece of code written will eventually become technical debt – a process that we can only slow down with great discipline – loggers rot at an unbelievable speed. After a while, we find ourselves fixing problems caused by loggers more often than the loggers give us useful information.

So how can we manage this mess with loggers and turn them into one of our allies rather than legacy ghosts haunting us from past development mistakes?

“State of The Art”

Before I dive deeper into my proposed solution, let’s define a concrete problem statement based on my observations.

So what exactly is logging? Here's an interesting and on-point one-liner that I found from Colin Eberhardt’s article:

Logging is the process of recording application actions and state to a secondary interface.

This is exactly how logging is woven into systems. We all seem to subconsciously agree that loggers don't belong to any particular layers of our systems. Instead, we consider them to be application-wide and shared amongst different components.

A much approved answer on StackOverflow

A much approved answer on StackOverflow

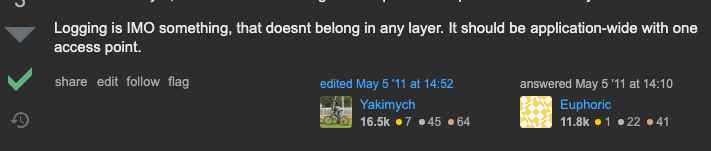

A simple diagram where logging has been fit into a system that is designed with clean architecture would look something like this:

We can safely say that logging itself is a subsystem within our application. And we can safely say that, without careful consideration, it often spirals out of control faster than we think.

While designing logging to be a subsystem within our applications is not wrong, the traditional perception of logging (with 4 to 6 levels of info, warn, error, debug, and so on) often makes developers focus on the wrong thing. It makes us focus on the format rather than the actual purpose of why we are writing logs.

This is one of the reasons why we log errors out without thinking twice about how to handle them. It's also why we log at every step of our code while ironically being unable to debug effectively if there is a production issue.

This is why I am proposing an alternative framework for logging and in turn, how we can design logging into our systems reliably.

The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

This is a framework for how I think we should strategize our logging. It has three – and only three – categories or concerns for our logs.

First rule of logging: Don’t log

Overlogging is detrimental to our teams’ productivity and ability to handle business-as-usual operations.

There’re tons of reasons why we should not “Log whenever you can” as advised by some observability fanfare. Logging means more code to maintain, it incurs expense in terms of system performance, and more logging subjects us to more data privacy regulatory audits.

If you need more reasons to refrain from logging, check out this post by Nikita Sobolev or this post by Jeff Atwood.

Nevertheless, I’m not advising that you eliminate logs altogether. I think logging, used correctly, can significantly help us keep our systems running reliably.

I’m just proposing we start without logging and work our way up to identify places where we need to log, rather than “log everywhere as we might need to look at them”.

My rule of thumb for adding a line of logging is “if we can’t pin down an exact reason or a scenario when we will look at the log, don’t log".

With that being said, how can we safely introduce logging when it’s absolutely necessary? How should we structure our logs and format their content? What information is necessary to include in logs?

The Ugly

These are the first type of logs that I want to describe, and they are also the ones that I find least frequently. (If we find them too often, we might have bigger issues in our systems!)

“The Ugly” is the kind of log under catastrophic or unexpected scenarios that requires immediate action (like catastrophic errors that need an application restart). We can argue that, under these circumstances, it makes more sense to use alerting tools like Sentry.

Nevertheless, an error log might still be useful to provide ourselves with more context surrounding these errors which are not available in their stack trace. But they could help with reproducing these errors, like user inputs.

Just like the errors that they accompany, these logs should be kept to a minimum in our code and placed in a single location. They should also be designed/documented in the spec as a required system behavior for error handling. Also, they should be woven into the source code around where the error handling happens.

While format and level for “The Ugly” logs are completely preferential on a team-by-team basis, I would recommend using log.error or log.fatal before a graceful shutdown and restart of the application. You should also attach the full error stack trace and the function or requests’ input data for reproduction if necessary.

The Bad

“The Bad” is the type of logs that addresses expected, handled errors like network issues and user input validation. This type of log only requires developers’ attention if there’s an anomaly with them.

Together with a monitor set up to alert developers upon an error, these logs are handy to mitigate potential serious infrastructure or security problems.

This type of log should be spec-ed inside error handling technical requirements as well, and can actually be bundled if we are handling expected and unexpected errors in the same code location.

Based on the nature of what they are making “visible” for developers, log.warn or log.error can be used for “The Bad” logs given a team's convention.

The Good

Last but definitely not least, “The Good” is the type of log that should appear most often in our source code – but it's often the most difficult to get right. “The Good” kind of logs are those associated with the “happy” steps of our applications, indicating the success of operations.

For its very nature of indicating starting/successful execution operations in our system, “The Good” is often abused by developers who are seduced by the mantra “Just one more bit of data in the log, we might need it”.

Again, I would circle back to our very first rule of logging: “Don’t log unless you absolutely have to”. To prevent this kind of over-logging from happening, we should document “The Good” as part of our technical requirements complementing the main business logic.

On top of that, for every single one of “The Good” logs that are inside our technical spec, they need to pass the litmus test: are there any circumstances under which we would look at the log (be it a customer support request, an external auditor’s inquiry)? Only this way will log.info not be a dreaded legacy that obscures developers’ vision into our applications.

The Rest (That You Need to Know)

By now I assume you've noticed that the general theme of my proposed logging strategy revolves around clear and specific documenting of the log's purpose. It is important that we treat logging as part of our requirements, and that we're specific about what keywords and messages we want to tag in each log's context for them to be effectively indexed.

Only by doing that can we be aware of each and every log that we produce, and in turn, have a clear vision into our systems.

As logs are upgraded to first-class citizens with concrete technical requirements in our specs, the implications are that they would need to be:

- maintained and updated as the business and technical requirements evolve

- covered by unit and integration tests

This might sound like a lot of extra work to get our logs right. However, I argue that this is the kind of attention and effort logging deserves so it can be useful.

Serve our logs, and we will be rewarded splendidly!

A Practical Migration Guide

I reckon there’s no use for a new logging strategy (or any new strategies/frameworks for that matter) for legacy projects if there’s no way of moving them from their messy state to the proposed ideal.

So I have a three-step general plan for anyone who is frustrated with their system's logs and is willing to invest the time to log more effectively.

Identify The Usual Suspects

Since the idea is to reduce garbage logs, our first step is to identify where the criminals are hiding. With the powerful text editors and IDEs we have nowadays (or grep if you are reading this in the past through a window-to-the-future), all occurrences of logging can be easily identified.

A document (or spreadsheet if you would like to be organised) documenting all of these logging occurrences might be necessary if there are too many of them.

Convict Them Bad Actors!

After identifying all suspects, it’s time to weed out the bad apples. Logs which are duplicated or unreachable are low hanging fruits that we can immediately eliminate from our source code.

For the rest of our logging occurrences, it’s time to involve other stakeholders like the “inception” engineer who started the project (if that is possible), product managers, customer support, or compliance folks to answer the question: Do we need each one of these logs, and if so, what are they being used for?

Light At the End of the Tunnel

Now that we have a narrowed-down list of absolutely necessary logs, turning them into technical requirements with documented purpose for each one of them is essential to nail down a contract (or we can call it specification) for our logging subsystem. Ask yourself what to do when a log.error happens, and who are we log.info-ing for?

After this, it’s just a matter of discipline in the same way that we write and maintain software in general. Let's all work together and make logging awesome!

You can reach out to me on Twitter with any questions or comments.