When first introduced to Git, it's typical for developers to feel uncomfortable with the process.

You might feel uncertainty when encountering the Git commit message, unsure how to properly summarize the changes you've made and why you've made them. But the earlier in your career you can develop good committing habits, the better.

Have you ever wondered how you can improve your Git commit messages? This guide outlines steps to elevate your commit messages that you can start implementing today.

This article assumes you already understand basic Git workflow. If not, I suggest reading through the Git Handbook.

It is also important to note that you should follow your team's conventions first and foremost. These tips are based on suggestions based upon research and general consensus from the community. But by the end of this article you may have some implementations to suggest that may help your team's workflow.

I think git enters a whole other realm the moment you start working in teams -- there are so many cool different flows and ways that people can commit code, share code, and add code to your repo open-source or closed-source-wise. — Scott Tolinski, Syntax.fm.

Why should you write better commit messages?

I challenge you to open up a personal project or any repository for that matter and run git log to view a list of old commit messages. The vast majority of us who have run through tutorials or made quick fixes will say "Yep... I have absolutely no idea what I meant by 'Fix style' 6 months ago."

Perhaps you have encountered code in a professional environment where you had no idea what it was doing or meant for. You've been left in the dark without code comments or a traceable history, and even wondering "what are the odds this will break everything if I remove this line?"

Back to the Future

By writing good commits, you are simply future-proofing yourself. You could save yourself and/or coworkers hours of digging around while troubleshooting by providing that helpful description.

The extra time it takes to write a thoughtful commit message as a letter to your potential future self is extremely worthwhile. On large scale projects, documentation is imperative for maintenance.

Collaboration and communication are of utmost importance within engineering teams. The Git commit message is a prime example of this. I highly suggest setting up a convention for commit messages on your team if you do not already have one in place.

The Anatomy of a Commit Message

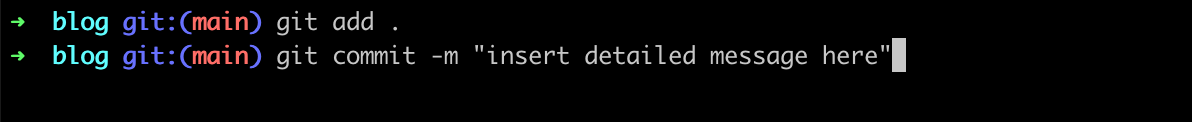

Basic:

git commit -m <message>

Detailed:

git commit -m <title> -m <description>

5 Steps to Write Better Commit Messages

Let's summarize the suggested guidelines:

- Capitalization and Punctuation: Capitalize the first word and do not end in punctuation. If using Conventional Commits, remember to use all lowercase.

- Mood: Use imperative mood in the subject line. Example –

Add fix for dark mode toggle state. Imperative mood gives the tone you are giving an order or request. - Type of Commit: Specify the type of commit. It is recommended and can be even more beneficial to have a consistent set of words to describe your changes. Example: Bugfix, Update, Refactor, Bump, and so on. See the section on Conventional Commits below for additional information.

- Length: The first line should ideally be no longer than 50 characters, and the body should be restricted to 72 characters.

- Content: Be direct, try to eliminate filler words and phrases in these sentences (examples: though, maybe, I think, kind of). Think like a journalist.

How to Find Your Inner Journalist

I never quite thought my Journalism minor would benefit my future career as a Software Engineer, but here we are!

Journalists and writers ask themselves questions to ensure their article is detailed, straightforward, and answers all of the reader's questions.

When writing an article they look to answer who, what, where, when, why and how. For committing purposes, it is most important to answer the what and why for our commit messages.

To come up with thoughtful commits, consider the following:

- Why have I made these changes?

- What effect have my changes made?

- Why was the change needed?

- What are the changes in reference to?

Assume the reader does not understand what the commit is addressing. They may not have access to the story addressing the detailed background of the change.

Don't expect the code to be self-explanatory. This is similar to the point above.

It might seem obvious to you, the programmer, if you're updating something like CSS styles since it is visual. You may have intimate knowledge on why these changes were needed at the time, but it's unlikely you will recall why you did that hundreds of pull requests later.

Make it clear why that change was made, and note if it may be crucial for the functionality or not.

See the differences below:

git commit -m 'Add margin'git commit -m 'Add margin to nav items to prevent them from overlapping the logo'

It is clear which of these would be more useful to future readers.

Pretend you're writing an important newsworthy article. Give the headline that will sum up what happened and what is important. Then, provide further details in the body in an organized fashion.

In filmmaking, it is often quoted "show, don't tell" using visuals as the communication medium compared to a verbal explanation of what is happening.

In our case, "tell, don't [just] show" – though we have some visuals at our disposal such as the browser, most of the specifics come from reading the physical code.

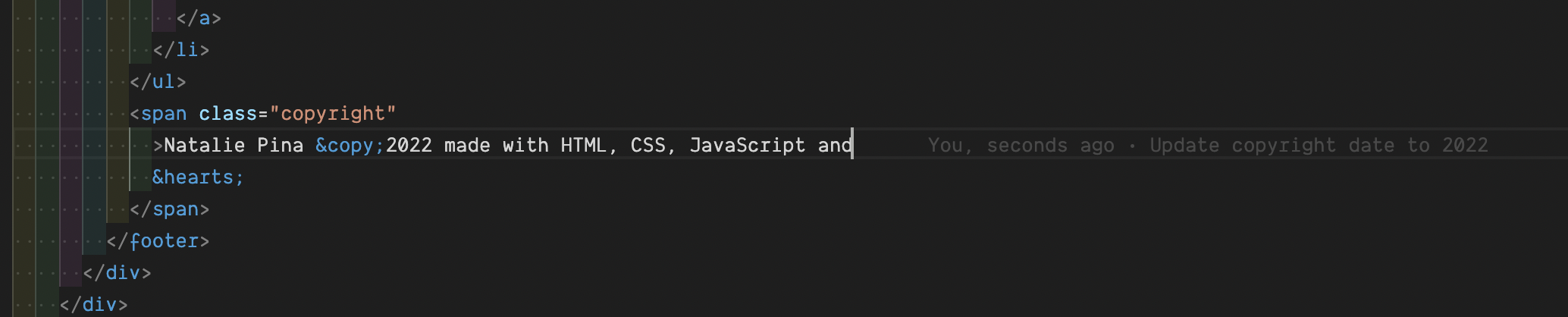

If you're a VSCode user, download the Git Blame extension. This is a prime example of when useful commit messages are helpful to future developers.

This plugin will list the person who made the change, the date of the changes, as well as the commit message commented inline.

Imagine how useful this could be in troubleshooting a bug or back-tracing changes made. Other honorable mentions to see Git historical information are Git History and GitLens.

Conventional Commits

Now that we've covered basic commit structure of a good commit message, I'd like to introduce Conventional Commits to help provide some detail on creating solid commit messages.

At D2iQ, we use Conventional Commit which is a great practice among engineering teams. Conventional Commit is a formatting convention that provides a set of rules to formulate a consistent commit message structure like so:

<type>[optional scope]: <description>

[optional body]

[optional footer(s)]

The commit type can include the following:

feat– a new feature is introduced with the changesfix– a bug fix has occurredchore– changes that do not relate to a fix or feature and don't modify src or test files (for example updating dependencies)refactor– refactored code that neither fixes a bug nor adds a featuredocs– updates to documentation such as a the README or other markdown filesstyle– changes that do not affect the meaning of the code, likely related to code formatting such as white-space, missing semi-colons, and so on.test– including new or correcting previous testsperf– performance improvementsci– continuous integration relatedbuild– changes that affect the build system or external dependenciesrevert– reverts a previous commit

The commit type subject line should be all lowercase with a character limit to encourage succinct descriptions.

The optional commit body should be used to provide further detail that cannot fit within the character limitations of the subject line description.

It is also a good location to utilize BREAKING CHANGE: <description> to note the reason for a breaking change within the commit.

The footer is also optional. We use the footer to link the JIRA story that would be closed with these changes for example: Closes D2IQ-<JIRA #> .

Full Conventional Commit Example

fix: fix foo to enable bar

This fixes the broken behavior of the component by doing xyz.

BREAKING CHANGE

Before this fix foo wasn't enabled at all, behavior changes from <old> to <new>

Closes D2IQ-12345

To ensure that these committing conventions remain consistent across developers, commit message linting can be configured before changes are able to be pushed up. Commitizen is a great tool to enforce standards, sync up semantic versioning, along with other helpful features.

To aid in adoption of these conventions, it's helpful to include guidelines for commits in a contributing or README markdown file within your projects.

Conventional Commit works particularly well with semantic versioning (learn more at SemVer.org) where commit types can update the appropriate version to release. You can also read more about Conventional Commits here.

Commit Message Comparisons

Review the following messages and see how many of the suggested guidelines they check off in each category.

Good

feat: improve performance with lazy load implementation for imageschore: update npm dependency to latest versionFix bug preventing users from submitting the subscribe formUpdate incorrect client phone number within footer body per client request

Bad

fixed bug on landing pageChanged styleoopsI think I fixed it this time?- empty commit messages

Conclusion

Writing good commit messages is an extremely beneficial skill to develop, and it helps you communicate and collaborate with your team. Commits serve as an archive of changes. They can become an ancient manuscript to help us decipher the past, and make reasoned decisions in the future.

There is an existing set of agreed-upon standards we can follow, but as long as your team agrees upon a convention that is descriptive with future readers in mind, there will undoubtedly be long-term benefits.

In this article, we've learned some tactics to level up our commit messages. How do you think these techniques can improve your commits?

I hope you've learned something new, thanks for reading!

Connect with me on Twitter @ui_natalie.