By Cory Kennedy-Darby

I belong to a team that provides internal services exposed through an API to various other teams within the company. These teams have become increasingly reliant on the services we provide.

Without sounding egotistical, these services are likely the most critical in the company. When these services are not entirely operational and stable, it impacts nearly all other teams, and has an enormous direct impact on revenue.

Internally, other teams in the company using our service are referenced as “clients.” For clarity sake, this article will treat the terms “clients” and “teams” as interchangeable.

Wednesday — we start receiving an enormous volume of requests

I get into the office, get some coffee and begin my day by checking our metrics and logs. Most people in the company already knew from the night before that there were a couple small hiccups with the load balancers that host our service. My manager wants to me to focus on an important initiative, and send all other unrelated tasks to him.

A couple of hours into my day I notice that one of our error log emails has a massive spike in a validation error. These validation errors are nothing special. We log to notify any client that sends us incorrect payload parameters that don’t match the validation rules.

The team I belong to hadn’t deployed any changes, infrastructure was in a healthy state, and nothing was out of place on our side to warrant such a massive increase.

My manager made it clear earlier that I should pass off to him anything that isn’t related to my current project I’m working on. I quickly realize I’ve made a mistake when I ask him where can I find the team lead of the team that is sending us all these validation errors.

The mistake is the moment I ask him this question he wants to know why I’m asking. The short version is he sees this as me not being focused on the initiative, and explains he’ll handle the validation errors. Shortly after our conversation, I get an email CC’ing me with the other team pointing out their issue to them.

All sudden there’s panic in the office

There is a flurry of emails about issues with our service, and everyone points the finger at the prior issue the night before with the load balancers.

I’m pulled off the initiative to handle the task of dealing with operations and the data center crew to deal with the load balancers. After some discussion, they decide to start rerouting portions of our traffic to other load balancers.

Magically the load balancers begin to stabilize.

The calm before the storm

The panic in the office disappears and everything goes back to running smoothly. After a couple of hours, the issue seems to begin to reappear and once again our service becomes compromised by an enormous amount of requests.

Ding!

The error log email comes in, and I notice those validation errors are reappearing again. I had been so focused on dealing with the data center that I hadn’t noticed they had stopped when the load balancers became stable.

Hold on! I pull up our Kibana dashboard to see our requests over time and compare the timestamps of the validation errors and the total requests over time. They are nearly an exact match.

I am fairly confident this is the issue, and I decide that I’m not repeating the same mistake from the morning. I ask a colleague where the other team is located and head there armed with the knowledge of the correlation between when the spikes happen and when everything becomes unstable.

Within 10 minutes of explaining the situation to the other team, they realize that this lines up exactly with when they deployed a feature, when they disabled the feature, and when it was accidentally redeployed.

They disable the feature on their side, and our service returns to stability. The feature they had deployed had a bug that would call our service in all situations, even when it wasn’t required.

Monday — ~600% amount of requests to an endpoint

The weekend passes, and there hadn’t been any issues with our service since the incident on Wednesday. Monday starts off normal without any issues, but by the end of the work day, our service begins to become unstable.

Quickly glancing through the Kibana events and our access logs, I notice what appears to be an insane amount of requests coming from a single team. The same team from Wednesday.

I rush off to that team’s area in the company and explain the details, asking if they by mistake relaunched the buggy feature from Wednesday.

To be sure that the feature hadn’t been deployed again by mistake, they reviewed their deployment logs and verified on git that the feature hadn’t mistakenly been merged into another branch.

The feature from Wednesday had not been redeployed.

I returned to my desk and began chatting with the data center operations team. The situation at this point has become severe because of the time the service has been impacted. The operations team is investigating, and I’m sitting waiting for an answer when the VP of operations shows up.

He’s clearly not happy because our API impacts a lot of products and services that are from the operations side of the business. He has some questions about bypassing our service, utilizing some fallback methods, and an ETA on the service returning to normal conditions.

A couple more minutes pass and then everything stabilizes.

Fixed? Not unless I believe in unicorns and mythical creatures

The data center operations team explains that a feature on our stage server was causing the load balancer processes to keep crashing. I call BS on their answer because this feature had been successfully running without any issues for nearly two months straight. The other reason I wasn’t willing to accept their answer was I had noticed on our Kibana dashboard that our total requests had roughly quadrupled.

It seemed too crazy that such a stable feature on our staging servers would randomly start causing such large issues.

Tuesday — Stakeholders Want Answers

Tuesday morning my manager asks me to deal with providing a clear outline of the events that happened on Monday for him to write up an incident report for the stakeholders.

The night before I spent a lot of time reflecting on the recent situations and I realized that a significant pain point was using our Kibana dashboard. Our Kibana dashboard is amazing when you want to see all requests, but with our current mapping, it’s hard to drill down and isolate requests from a specific client.

The problem? It’s going to take a bit of work, nobody has assigned me to do this, and this isn’t the original task given to me. On the spot I decide that I’m going to build this out. High performing individuals don’t ask permission to do their job. They go and deliver results.

High performing individuals don’t ask permission to do their job. They go and deliver results.

- Cory Darby

I begin to hack together a script that uses regular expressions with our Elasticsearch that passes the results into Highcharts. During this, our CTO stops by to ask about the situation that unfolded on Monday. I explain that there’s no evidence at the moment, but that my gut feeling from what I saw in the logs, graphs, and metrics is that the other team’s cache died. The other team’s cache dying would force them to make an enormous amount of requests to our service.

He leaves to get answers from the other team, and I finish hacking the script together. It isn’t elegant code but it gets the job done, and it means we’re not in the dark anymore.

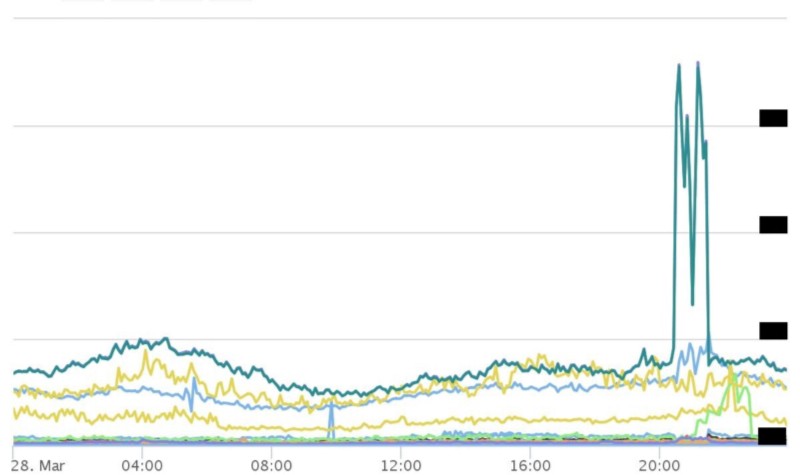

Just 10 minutes after finishing, our CTO returns. He explains that the other team can’t find any issues on their side. At this point I show him the graph, which shows every request grouped by every team using our service:

The giant spike in the graph above is the other team that had just explained that everything looked healthy on their side.

Further investigation by the other team showed that a new feature they launched required a significant amount of caching. The rules they have in place with their cache were to evict the oldest cached objects to make room for new ones. The evicted data happened to be all the cached data for our service.

Their cache was working, but it didn’t have any of our service cached anymore. The other team was hitting us for nearly every request.

Areas of Improvement

After any major engineering incident, it’s important to cover the cause, solution, prevention, and any pain points the incident exposed.

Insightful metrics & monitoring

Clients using our services need better insights into their usage. On our side, we will be providing easier ways to drill down for specific metrics.

After these events, it’s clear that we will need to create an actual dashboard for both the clients and for ourselves. The dashboard will replace the script I built to push data into the Highchart graph. The dashboard graphs will have monitoring on the data being received so they can provide the earliest alerting.

Reduce team Silos

Ideally, we would allow other teams in the company to be able to push pinpoints to the dashboard when they deploy to their production environments. If the requests from a single team increase substantially after a deployment, the deployment is most likely responsible for this spike.

Communication

During these outages, stakeholders created a lot of distraction throughout the company. These distractions take the form of emails, chat messages, and individuals showing up at the team’s space to ask about the service.

To reduce the number of distractions, we will have an internal dashboard that includes the current status and the events as they unfold. The events will include time of creation, a description of the situation, and an estimated time of recovery (if known).

Wrapping up

It’s never a question of “if” there will be an outage. It’s a question of “when.”

Every incident — no matter how small — is a learning opportunity to prevent things like this from happening again, reduce its negative impact, and become better-prepared.

Disclaimer: These are my opinions, nobody else’s, and they do not reflect my employer’s.