By Diogo Spínola

JavaScript is synchronous. This means that it will execute your code block by order after hoisting. Before the code executes, var and function declarations are “hoisted” to the top of their scope.

This is an example of a synchronous code:

console.log('1')

console.log('2')

console.log('3')

This code will reliably log “1 2 3".

Asynchronous requests will wait for a timer to finish or a request to respond while the rest of the code continues to execute. Then when the time is right a callback will spring these asynchronous requests into action.

This is an example of an asynchronous code:

console.log('1')

setTimeout(function afterTwoSeconds() {

console.log('2')

}, 2000)

console.log('3')

This will actually log “1 3 2”, since the “2” is on a setTimeout which will only execute, by this example, after two seconds. Your application does not hang waiting for the two seconds to finish. Instead it keeps executing the rest of the code and when the timeout is finished it returns to afterTwoSeconds.

You may ask “Why is this useful?” or “How do I get my async code to become sync?”. Hopefully I can show you the answers.

“The problem”

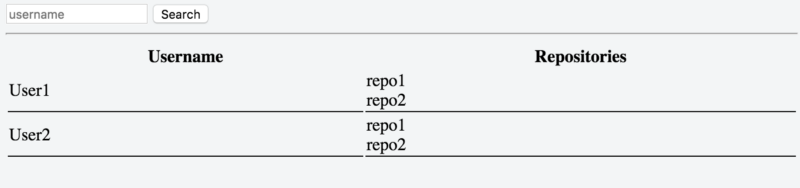

Let us say our goal is to search for a GitHub user and get all the repositories of that user. The thing is we don’t know the exact name of the user. So we have to list all the users with similar name and their respective repositories.

Doesn’t need to super fancy, something like this

In these examples the request code will use XHR (XMLHttpRequest). You can replace it with jQuery $.ajax or the more recent native approach called fetch. Both will give you the promises approach out of the gate.

It will be slightly changed depending on your approach but as a starter:

// url argument can be something like 'https://api.github.com/users/daspinola/repos'

function request(url) {

const xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.timeout = 2000;

xhr.onreadystatechange = function(e) {

if (xhr.readyState === 4) {

if (xhr.status === 200) {

// Code here for the server answer when successful

} else {

// Code here for the server answer when not successful

}

}

}

xhr.ontimeout = function () {

// Well, it took to long do some code here to handle that

}

xhr.open('get', url, true)

xhr.send();

}

Remember that in these examples the important part is not what the end result of the code is. Instead your goal should be to understand the differences of the approaches and how you can leverage them for your development.

Callback

You can save a reference of a function in a variable when using JavaScript. Then you can use them as arguments of another function to execute later. This is our “callback”.

One example would be:

// Execute the function "doThis" with another function as parameter, in this case "andThenThis". doThis will execute whatever code it has and when it finishes it should have "andThenThis" being executed.

doThis(andThenThis)

// Inside of "doThis" it's referenced as "callback" which is just a variable that is holding the reference to this function

function andThenThis() {

console.log('and then this')

}

// You can name it whatever you want, "callback" is common approach

function doThis(callback) {

console.log('this first')

// the '()' is when you are telling your code to execute the function reference else it will just log the reference

callback()

}

Using the callback to solve our problem allows us to do something like this to the request function we defined earlier:

function request(url, callback) {

const xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.timeout = 2000;

xhr.onreadystatechange = function(e) {

if (xhr.readyState === 4) {

if (xhr.status === 200) {

callback(null, xhr.response)

} else {

callback(xhr.status, null)

}

}

}

xhr.ontimeout = function () {

console.log('Timeout')

}

xhr.open('get', url, true)

xhr.send();

}

Our function for the request will now accept a callback so that when a request is made it will be called in case of error and in case of success.

const userGet = `https://api.github.com/search/users?page=1&q=daspinola&type=Users`

request(userGet, function handleUsersList(error, users) {

if (error) throw error

const list = JSON.parse(users).items

list.forEach(function(user) {

request(user.repos_url, function handleReposList(err, repos) {

if (err) throw err

// Handle the repositories list here

})

})

})

Breaking this down:

- We make a request to get a user’s repositories

- After the request is complete we use callback

handleUsersList - If there is no error then we parse our server response into an object using

JSON.parse - Then we iterate our user list since it can have more than one

For each user we request their repositories list.

We will use the url that returned per user in our first response

We callrepos_urlas the url for our next requests or from the first response - When the request has completed the callback, we will call

This will handle either its error or the response with the list of repositories for that user

Note: Sending the error first as parameter is a common practice especially when using Node.js.

A more “complete” and readable approach would be to have some error handling. We would keep the callback separate from the request execution.

Something like this:

try {

request(userGet, handleUsersList)

} catch (e) {

console.error('Request boom! ', e)

}

function handleUsersList(error, users) {

if (error) throw error

const list = JSON.parse(users).items

list.forEach(function(user) {

request(user.repos_url, handleReposList)

})

}

function handleReposList(err, repos) {

if (err) throw err

// Handle the repositories list here

console.log('My very few repos', repos)

}

This ends up having problems like racing and error handling issues. Racing happens when you don’t control which user you will get first. We are requesting the information for all of them in case there is more than one. We are not taking an order into account. For example, user 10 can come first and user 2 last. We have a possible solution later in the article.

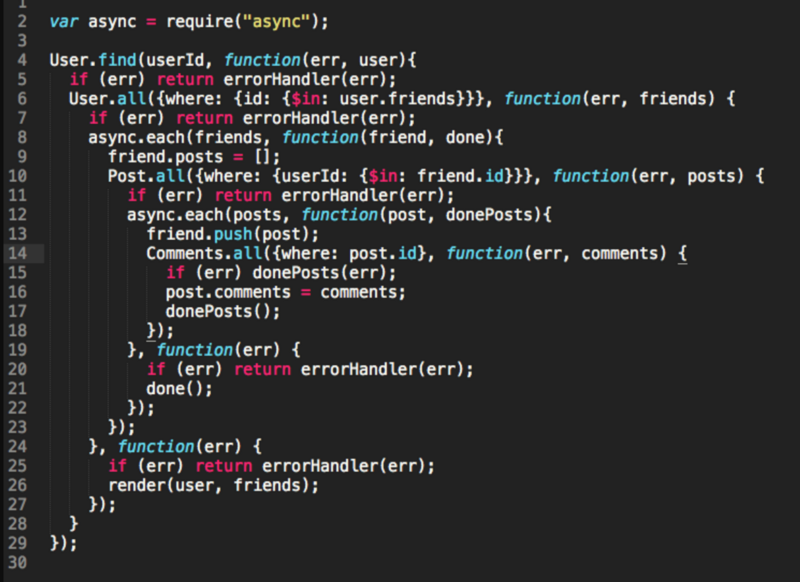

The main problem with callbacks is that maintenance and readability can become a pain. It sort of already is and the code does hardly anything. This is known as callback hell which can be avoided with our next approach.

Promises

Promises you can make your code more readable. A new developer can come to the code base and see a clear order of execution to your code.

To create a promise you can use:

const myPromise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

// code here

if (codeIsFine) {

resolve('fine')

} else {

reject('error')

}

})

myPromise

.then(function whenOk(response) {

console.log(response)

return response

})

.catch(function notOk(err) {

console.error(err)

})

Let us decompose it:

- A promise is initialized with a

functionthat hasresolveandrejectstatements - Make your async code inside the

Promisefunctionresolvewhen everything happens as desired

Otherwisereject - When a

resolveis found the.thenmethod will execute for thatPromise

When arejectis found the.catchwill be triggered

Things to bear in mind:

resolveandrejectonly accept one parameterresolve(‘yey’, ‘works’)will only send ‘yey’ to the.thencallback function- If you chain multiple

.then

Add areturnif you want the next.thenvalue not to beundefined - When a

rejectis caught with.catchif you have a.thenchained to it

It will still execute that.then

You can see the.thenas an “always executes” and you can check an example in this comment - With a chain on

.thenif an error happens on the first one

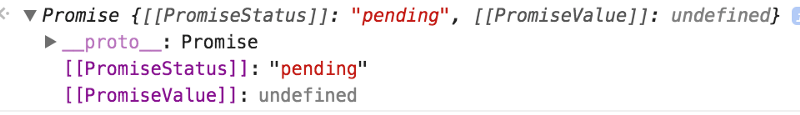

It will skip subsequent.thenuntil it finds a.catch - A promise has three states

pending - When waiting for a

resolveorrejectto happen

resolved

rejected - Once it’s in a

resolvedorrejectedstate

It cannot be changed

Note: You can create promises without the function at the moment of declarations. The way that I’m showing it is only a common way of doing it.

“Theory, theory, theory…I’m confused” you may say.

Let’s use our request example with a promise to try to clear things up:

function request(url) {

return new Promise(function (resolve, reject) {

const xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.timeout = 2000;

xhr.onreadystatechange = function(e) {

if (xhr.readyState === 4) {

if (xhr.status === 200) {

resolve(xhr.response)

} else {

reject(xhr.status)

}

}

}

xhr.ontimeout = function () {

reject('timeout')

}

xhr.open('get', url, true)

xhr.send();

})

}

In this scenario when you execute request it will return something like this:

const userGet = `https://api.github.com/search/users?page=1&q=daspinola&type=Users`

const myPromise = request(userGet)

console.log('will be pending when logged', myPromise)

myPromise

.then(function handleUsersList(users) {

console.log('when resolve is found it comes here with the response, in this case users ', users)

const list = JSON.parse(users).items

return Promise.all(list.map(function(user) {

return request(user.repos_url)

}))

})

.then(function handleReposList(repos) {

console.log('All users repos in an array', repos)

})

.catch(function handleErrors(error) {

console.log('when a reject is executed it will come here ignoring the then statement ', error)

})

This is how we solve racing and some of the error handling problems. The code is still a bit convoluted. But its a way to show you that this approach can also create readability problems.

A quick fix would be to separate the callbacks like so:

const userGet = `https://api.github.com/search/users?page=1&q=daspinola&type=Users`

const userRequest = request(userGet)

// Just by reading this part out loud you have a good idea of what the code does

userRequest

.then(handleUsersList)

.then(repoRequest)

.then(handleReposList)

.catch(handleErrors)

function handleUsersList(users) {

return JSON.parse(users).items

}

function repoRequest(users) {

return Promise.all(users.map(function(user) {

return request(user.repos_url)

}))

}

function handleReposList(repos) {

console.log('All users repos in an array', repos)

}

function handleErrors(error) {

console.error('Something went wrong ', error)

}

By looking at what userRequest is waiting in order with the .then you can get a sense of what we expect of this code block. Everything is more or less separated by responsibility.

This is “scratching the surface” of what Promises are. To have a great insight on how they work I cannot recommend enough this article.

Generators

Another approach is to use the generators. This is a bit more advance so if you are starting out feel free to jump to the next topic.

One use for generators is that they allow you to have async code looking like sync.

They are represented by a * in a function and look something like:

function* foo() {

yield 1

const args = yield 2

console.log(args)

}

var fooIterator = foo()

console.log(fooIterator.next().value) // will log 1

console.log(fooIterator.next().value) // will log 2

fooIterator.next('aParam') // will log the console.log inside the generator 'aParam'

Instead of returning with a return, generators have a yield statement. It stops the function execution until a .next is made for that function iteration. It is similar to .then promise that only executes when resolved comes back.

Our request function would look like this:

function request(url) {

return function(callback) {

const xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.onreadystatechange = function(e) {

if (xhr.readyState === 4) {

if (xhr.status === 200) {

callback(null, xhr.response)

} else {

callback(xhr.status, null)

}

}

}

xhr.ontimeout = function () {

console.log('timeout')

}

xhr.open('get', url, true)

xhr.send()

}

}

We want to have the url as an argument. But instead of executing the request out of the gate we want it only when we have a callback to handle the response.

Our generator would be something like:

function* list() {

const userGet = `https://api.github.com/search/users?page=1&q=daspinola&type=Users`

const users = yield request(userGet)

yield

for (let i = 0; i<=users.length; i++) {

yield request(users[i].repos_url)

}

}

It will:

- Wait until the first

requestis prepared - Return a

functionreference expecting acallbackfor the firstrequest

Ourrequestfunction accepts aurl

and returns afunctionthat expects acallback - Expect a

usersto be sent in the next.next - Iterate over

users - Wait for a

.nextfor each of theusers - Return their respective callback function

So an execution of this would be:

try {

const iterator = list()

iterator.next().value(function handleUsersList(err, users) {

if (err) throw err

const list = JSON.parse(users).items

// send the list of users for the iterator

iterator.next(list)

list.forEach(function(user) {

iterator.next().value(function userRepos(error, repos) {

if (error) throw repos

// Handle each individual user repo here

console.log(user, JSON.parse(repos))

})

})

})

} catch (e) {

console.error(e)

}

We could separate the callback functions like we did previously. You get the deal by now, a takeaway is that we now can handle each individual user repository list individually.

I have mixed felling about generators. On one hand I can get a grasp of what is expected of the code by looking at the generator.

But its execution ends up having similar problems to the callback hell.

Like async/await, a compiler is recommended. This is because it isn’t supported in older browser versions.

Also it isn’t that common in my experience. So it may generate confusing in codebases maintained by various developers.

An awesome insight of how generators work can be found in this article. And here is another great resource.

Async/Await

This method seems like a mix of generators with promises. You just have to tell your code what functions are to be async. And what part of the code will have to await for that promise to finish.

sumTwentyAfterTwoSeconds(10)

.then(result => console.log('after 2 seconds', result))

async function sumTwentyAfterTwoSeconds(value) {

const remainder = afterTwoSeconds(20)

return value + await remainder

}

function afterTwoSeconds(value) {

return new Promise(resolve => {

setTimeout(() => { resolve(value) }, 2000);

});

}

In this scenario:

- We have

sumTwentyAfterTwoSecondsas being an async function - We tell our code to wait for the

resolveorrejectfor our promise functionafterTwoSeconds - It will only end up in the

.thenwhen theawaitoperations finish

In this case there is only one

Applying this to our request we leave it as a promise as seen earlier:

function request(url) {

return new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

const xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.onreadystatechange = function(e) {

if (xhr.readyState === 4) {

if (xhr.status === 200) {

resolve(xhr.response)

} else {

reject(xhr.status)

}

}

}

xhr.ontimeout = function () {

reject('timeout')

}

xhr.open('get', url, true)

xhr.send()

})

}

We create our async function with the needed awaits like so:

async function list() {

const userGet = `https://api.github.com/search/users?page=1&q=daspinola&type=Users`

const users = await request(userGet)

const usersList = JSON.parse(users).items

usersList.forEach(async function (user) {

const repos = await request(user.repos_url)

handleRepoList(user, repos)

})

}

function handleRepoList(user, repos) {

const userRepos = JSON.parse(repos)

// Handle each individual user repo here

console.log(user, userRepos)

}

So now we have an async list function that will handle the requests. Another async is needed in the forEach so that we have the list of repos for each user to manipulate.

We call it as:

list()

.catch(e => console.error(e))

This and the promises approach are my favorites since the code is easy to read and change. You can read about async/await more in depth here.

A downside of using async/await is that it isn’t supported in the front-end by older browsers or in the back-end. You have to use the Node 8.

You can use a compiler like babel to help solve that.

“Solution”

You can see the end code accomplishing our initial goal using async/await in this snippet.

A good thing to do is to try it yourself in the various forms referenced in this article.

Conclusion

Depending on the scenario you might find yourself using:

- async/await

- callbacks

- mix

It’s up to you what fits your purposes. And what lets you maintain the code so that it is understandable to others and your future self.

Note: Any of the approaches become slightly less verbose when using the alternatives for requests like $.ajax and fetch.

Let me know what you would do different and different ways you found to make each approach more readable.

This is Article 11 of 30. It is part of a project for publishing an article at least once a week, from idle thoughts to tutorials. Leave a comment, follow me on Diogo Spínola and then go back to your brilliant project!