by Erik Cannon

Coding bootcamps also teach you how to get rejected 10 times a day.

“You will have 60 minutes to complete the four coding challenges and have all of the tests pass to ‘true’. Any questions?”

There was a long silent pause.

“Great. Please begin.”

I opened up the Cloud9 document, cruised through the preliminary instructions and made my way down to the first method. Def first_n_evens(n) glared back at me in a mocking tone. It knew damn well I had no idea how to start the problem. Implement a blank array, start some sort of loop, or even insert a modulo operator — all fleeting thoughts on where I should start.

The pressure was palpable as I sat, slightly defeated, and looked for a starting path to the correct answer.

This was my shot at acceptance into an elite coding bootcamp, and the beginnings of a career in tech.

What had I gotten myself into?

Elevator to the Twilight Zone

In the most literal sense I was sitting in an office building in a trendy part of New York City just south of the ever pretentious Houston Street (pronounced “house-ton” for those of us not “in the know”) and just a few floors up from a Sephora Lounge.

The building wasn’t much to look at from the outside and offered even less aesthetic appeal on the inside.

A precarious elevator waited patiently in a tiny lobby to lift me to the middle floor, and spit me out into the front of an entirely open office space.

The space was long and narrow, offered a nice view out onto the city streets, a small kitchen and water-cooler, and was furnished with hardwood floors, bleach white walls, and row after row of black computer monitors.

Students were diligently ripping through lines of code and making the computer dance in ways that I had not seen since watching The Matrix.

“Hey, are you here for the Initiation Program?” asked an energetic — albeit slightly unkempt — individual to my right. Indeed I was.

The Initiation Program was a brainchild of this particular coding bootcamp. The idea of the program was to take seemingly capable individuals (judged on education history and SAT scores) with limited coding and computer science experience. It would get them to a place, in a span of two weeks, to where they would be able pass the entrance exam forced upon all bootcamp applicants.

A passed entrance exam would look incredibly favorable to the individual and would seem to allow automatic acceptance into the bootcamp which — if you trust the stats on their website — boasted a 98 percent job placement rate with median salaries of $89,000 in New York City, and even more in San Francisco.

To understand the appeal of such a coding bootcamp is to understand a deeper movement in which Michael Lewis aptly calls “The New New Thing.” The movement, as Lewis explains is the next big career breakthrough offering the possibility of riches, meaningful work, and a center-of-the-universe type appeal that brings together the smartest people of an era. This type of appeal is analogous to bond trading of the 80’s or “popy” boy-bands of the 90's.

Add into this equation an uncertain job market, the financial crisis of 2008, unprecedented mountains of student debt and you begin to understand the appeal of a three month bootcamp which in return for only a small, refundable deposit promises the fast track to a rewarding career. For a more eloquent description please see Ms. Huston’s article for the Wall Street Journal here.

To think that a coding bootcamp can take you from zero to coding hero in a matter of three months, on the surface seems ludicrous. After all, don’t accredited colleges offer four year degrees on the subject?

How can bootcamp alumni compete with a B.S. in computer science in the job market? What kind of jobs were bootcamp alums getting? Are we talking Product Engineer at Google or Administrative Assistant at Startup “X”? Also, how hard was coding anyway? I was determined to find out.

My First Day at Camp

Back at bootcamp headquarters all of the Initiation Program students were ushered to the back of the building and took a seat in rows of standard, boardroom-certified, black swivel chairs. The chairs looked forward onto a projector displaying a Macintosh home screen on the bleach white wall.

Confident students milled around up front, while nervous-looking students clamored their way to an empty swivel chair in the back. A few minutes after the scheduled starting time, what appeared, at first, as a confident looking Initiation Program student in a colorfully striped t-shirt, introduced himself as John, a senior bootcamp TA, and welcomed everyone to the program.

John was a young male with curly hair and above average height. He talked quickly and efficiently with a slightly nervous air as if continuously reminding himself to keep it together in the back of his head. After explaining a bit about himself and the objectives for the week, John motioned over to his six fellow TA’s sitting to his left. Each peered up from beyond their black monitors and with varying degrees of energy introduced themselves.

The TA’s were a colorful and, honestly, impressive group. Amongst the group were Fulbright scholars, Ivy League playwrights, high school valedictorians, mechanical engineers, and even a bearded McLovin doppelganger. The TA’s, as I came to find out, were the most recent bootcamp graduates who were still looking for employment and seemed to be bonded together with a handful of awkward jokes, high I.Q.’s, a love for computing, and a collective solidarity of not yet landing the job of their dreams. Their bonds were more surface level than deep connections and seemed to treat each other as mere acquaintances of circumstance as opposed to close personal friends.

John continued laying out the schedule for the week and we soon discovered the first matter of business was to break up the Initiation Program students into six distinct pods, each lead by a bootcamp TA. In the pods you would work together with a fellow student on coding exercises of the day as well as complete the assigned individual work that was hosted on GitHub (a programmer’s networking site where snippets of code can be easily shared).

By the end of the first week there would be an assessment to test how much you had learned and see if you’re ready for the real deal three month bootcamp. The assessment would also be offered once more at the end of the second week, for a shot at redemption should you not pass the first.

John finished up his introductory spiel and split us up into our pods. I was in Pod 4 and was lead by a TA named Sam. Sam was incredibly smart, but also incredibly distant. Unlike some of the other TA’s he put in the minimal amount of oversight required to still be considered a TA. Sam would be more likely to be found off alone at his computer than to seek out students needing help.

My Fellow Classmates

Sam instructed us to begin work on the self-paced material as he pulled each of us aside individually to get know us better and understand why we were interested in programming and this particular bootcamp. It was at this moment when I was finally able to get to meet some of my fellow classmates, who were just as, if not more, interesting than the TA’s.

There was a Japanese immigrant working in accounting, a college student who swore his brother had just landed an impressive coding job at a big financial firm, a bootcamp savant who had intently studied the pros and cons of each bootcamp and was here because it was truly the best, a pre-med student whose jaunt into medicine was cut short after discovering she was allergic to formaldehyde. There were countless others whose previous jobs were too dull, too unsatisfying, or too low paying and who wanted to be a part of this “new new thing.”

The majority of my classmates appeared to already hold an undergraduate degree and at least one entry level job. None were out of their 20’s, and from what I could tell, all seemed to be reasonably intelligent.

After working briefly on the assigned work, John announced that the first day of class had ended and I soon found myself stepping out onto the Manhattan sidewalk.

Walking out of the first day of class, I began to realize how odd yet somehow familiar the first day had felt. The bootcamp itself felt, in a way, like a traditional college class. There was a group full of young attentive students, active TA’s who had only just completed the required course giving them their TA credential, and a host of readings and practice problems.

The only thing that was noticeably absent was the teacher. There was no authoritative figure or omniscient Ph.D. to lead discussion. There wasn’t even as much as a thirty-two year old ex-programmer in a bootcamp emblazoned hoodie ready to distribute a few years of industry knowledge. There were young people, and only young people huddled together in the trenches trying to figure it out.

There was something very raw and scrappy to the whole organization. Something very refreshing and intoxicating. A feeling I can only imagine Larry and Sergei felt in the early years, before handing over the reigns to Eric Schmidt.

Starting to Code

Arriving home that night, and by home I mean a couch that a few old college buddies let me crash on, I was completely exhausted, mentally drained, yet somehow still completely excited to wake up and get started on this coding thing. I woke up the next morning and got to work. The concepts seemed simple enough. Anything inside quotes is a string. Letters can be set to equal variables. Okay I have seen this before. A method is a unit of work. Not bad, not bad. The first practice problems went smoothly enough and I was beginning to gain some confidence. Then came the homework problem.

The homework problem was a complete step up from the softball examples they interjected throughout the readings. I gave it my best effort than vowed to understand it better once I was in class. The homework problem was the first thing we went over at the start of every class and was the time I would consistently get the most confused.

The TA’s would ask for ways in which to start the problems and were immediately accompanied by throngs of raising hands. One eager volunteer would offer his or her way to solve the problem and the TA would immediately head down that path.

Analogous to a math problem, there are many ways to get to the correct answer or what you want the program to do. Each student was at different levels of experience and would offer up solutions that many of us had not previously seen before. Think of suggesting a trigonometric function when the rest of the class was still on addition. This was more frustrating than enlightening and some TA’s were better teachers than others. Ultimately, I felt as though these sessions lead to a mass panic in which students felt hopelessly behind the curve.

After the homework review, the next order of the day was the paired programming sessions. The paired programming sessions were some of my favorite times in the class. Not only did you get to bond with the other classmates, you also were able to see how another person approached the problem. This of course proved difficult when neither partner knew how to solve the problem, but as with most things two heads were better than one.

The thing that was most revealing about the paired programming sessions was how immediately the table was able to discern who “got it” and who did not. Some pairs would finish light years ahead of others and begin chatting about the weather, while others hadn’t finished reading the instructions.

What was even more interesting is how modest a lot of the top people were. They would often default to saying how tough the homework was or how nervous they were for the assessment. It was clear how skilled these programmers were, but their modesty in these situations was perhaps something that allowed them to bond with all of the other students who were struggling together.

The days came and went and I had a nice schedule going throughout the week. I would wake up, work out, and hit the code. I would study throughout the day before heading to class at night and soon was able to distinguish an array from a string, and a loop from a conditional. I would try the homework problem and then continue reading the assigned lessons until I found a new technique that might get me to the answer. Ultimately, I got more of them wrong than I did right, but I was incredibly impressed with how much I was able to learn in such little time, if I do say so myself.

Is Coding Fun?

Throughout the course I found coding to be incredibly addictive, all the while being incredibly frustrating and a knife's edge was all that was left to separate the two. The mental stimulation is very rewarding, similar to solving a tough Sudoku or crossword puzzle, however, the frustration was also very present.

When a single period can make the difference between success and failure attention to detail is key. Especially when you start adding hundreds and hundreds of layers of code. Also the computer science concepts can add Inception like complexity. Loops are used to execute the same block of code over and over and when loops are added inside other loops keeping track of what the computer is doing is similar to Leo trying to remember what dream he left his wife in.

Assessment Day

As the week was drawing to a close and the assessment day came ever closer I worked diligently to memorize as much as possible. All of my work was in vain, however, as a few minutes after the TA’s uploaded the assessment I soon realized I wasn’t where I needed to be. The problems were too advanced and in one short week I wasn’t able to memorize enough useful material to pass the exam.

A few students in neighboring pods felt hopeless and gave up early. Others tried until the last minute, but were unable to finish every problem. I don’t think anyone was able to pass that first exam, at least not anyone that I talked to, and there is some amount of comfort to be taken in that.

After the exam had finished and students were packing up to leave, I asked a TA about a mysterious decoration hanging on the otherwise spotless white walls. The decoration was labeled “Rejections” and in dry-erase marker listed a name followed by a number.

The TA explained that each number is the amount of companies that each full-time bootcamp student has been rejected from. The numbers were staggering and would seem more apt for a popular Instagram post as opposed to rejection letters. Numbers ranged from the low-twenties to mid-hundreds. The TA continued to explain that at the end of the three month coding class there is a three week job search where each student applies to ten jobs a day, with the help of the bootcamp’s management team.

Is it all worth it?

It was at that moment when I realized just how difficult the whole process was and what type of person these bootcamps were looking for. You invest three months of your life and code full time for upwards of 12 hours per day for a shot at a coveted programming position at a respectable company.

Right now the bootcamps can boast high salaries and high job placement rates, but as more and more bootcamps open and more and more people become apt at coding the market may soon become saturated with computer scientists.

There is no clear answer to this, as developing technology may keep demanding more and more people with coding ability at a rate that exceeds the amount of available coders.

With Uber testing its first fleet of self-driving cars and restaurants like Honeygrow running lean operations with computer software taking customer orders, perhaps there is reason to believe that this trend will continue into the foreseeable future.

Regardless, it seems safe enough to say that knowing at least some basic computer programming can only stand to benefit an individual heading into an increasingly technology heavy future, no matter the industry.

If you’re interested in coding and are 100% committed to the cause, there are some increasingly positive nuggets of information about coding bootcamps.

While they may be difficult to enter (this particular bootcamp had a less than 5% acceptance rate) 25 out of the 30 students or 83% of the most recent cohort had technical jobs within a few weeks. Also there is no up front fee for the bootcamp itself. The company takes a portion of your salary after you get a job to ensure that everyone’s goals are aligned.

Additionally, companies in the tech industry in general, tend to care less about accredited degrees as they do about how much of the information you know and what value you can add on your first day. A promising fact for those not wanting to go back to college for an additional bachelor's degree.

Still, coding bootcamps are no silver bullet. After gaining acceptance, a mountain of hard work lies ahead. Not everyone even finishes the bootcamp. With weekly exams — of which you can only fail one — and tough technical interviews from employers, there are many checks along the way to ensure that you know your stuff.

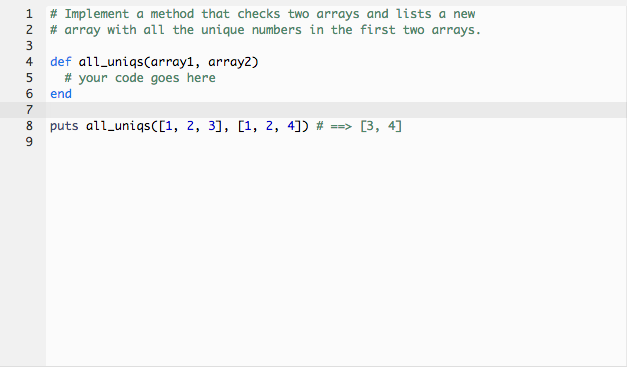

Think you’re up for the challenge? Take a look at a practice problem below.

My Path

As for me, I decided not to continue my pursuit of this particular coding bootcamp. I wasn’t ready for the type of commitment they would be expecting. I haven’t given up on coding though, as I fall into the camp of people that believe coding will be the number one skill to have heading into the next decade.

In the meantime I plan on working through Free Code Camp.

Who knows, maybe next year I’ll be in the trenches fighting for a seat at a coding bootcamp. Or maybe I’ll be a strong enough developer to just go out and get a job.

Only time will tell.

If you want to read more about tech, careers, and life’s tough questions, you can find some of my other work at Loose Cannon Publications and also on Twitter at @loosecannonpub.