React is one of the most popular JavaScript frameworks ever created, and I believe that it's one of the best tools out there.

The goal of this handbook is to provide a starter guide to learning React.

At the end of the book, you'll have a basic understanding of:

- What React is and why it's so popular

- How to install React

- React Components

- React State

- React Props

- Handling user events in React

- Lifecycle events in a React component

These topics will be the base upon which you will build in other more advanced React tutorials.

This book is especially written for JavaScript programmers who are new to React. So let's get started.

What is React?

React is a JavaScript library that aims to simplify the development of visual interfaces.

Developed at Facebook and released to the world in 2013, it drives some of the most widely used apps, powering Facebook and Instagram among countless other applications.

Its primary goal is to make it easy to reason about an interface and its state at any point in time. It does this by dividing the UI into a collection of components.

You might experience some initial difficulties when learning React. But once it "clicks", I guarantee it's going to be one of the best experiences you ever have. React makes many things easier, and its ecosystem is filled with great libraries and tools.

React in itself has a very small API, and you basically need to understand 4 concepts to get started:

- Components

- JSX

- State

- Props

We'll explore all of these in this book, and we'll leave the more advanced concepts to other tutorials. I will give you some pointers in the last section about how to move forward.

And you can download this handbook in PDF / ePub / Mobi format for free.

Summary of the handbook

- How much JavaScript you need to know to use React

- Why should you learn React?

- How to install React

- React Components

- Introduction to JSX

- Using JSX to compose a UI

- The difference between JSX and HTML

- Embedding JavaScript in JSX

- Managing state in React

- Component Props in React

- Data flow in a React application

- Handling user events in React

- Lifecycle events in a React component

- Where to go from here

How much JavaScript you need to know to use React

Before jumping straight into React, you should have a good understanding of some core JavaScript concepts.

You don't have to be a JavaScript expert, but I think you need a good overview of:

- Variables

- Arrow functions

- Work with objects and arrays using Rest and Spread

- Object and array destructuring

- Template literals

- Callbacks

- ES Modules

If those concepts sound unfamiliar, I've provided you with some links to find out more about those subjects.

Why should you learn React?

I highly recommend that any Web developer has at least a basic understanding of React.

That's because of a few reasons.

- React is very popular. As a developer, it's quite likely that you're going to work on a React project in the future. Perhaps an existing project, or maybe your team will want you to work on a brand new app based on React.

- A lot of tooling today is built using React at the core. Popular frameworks and tools like Next.js, Gatsby, and many others use React under the hood.

- As a frontend engineer, React is probably going to come up in a job interview.

Those are all good reasons, but one of the main reasons I want you to learn React is that it's great.

It promotes several good development practices, including code reusability and component-driven development. It is fast, it is lightweight, and the way it makes you think about the data flow in your application perfectly suits a lot of common scenarios.

How to install React

There are a few different ways to install React.

To start with, I highly recommend one approach, and that's using the officially recommended tool called create-react-app.

create-react-app is a command line application, aimed at getting you up to speed with React in no time.

You start by using npx, which is an easy way to download and execute Node.js commands without installing them.

See my npx guide here: https://flaviocopes.com/npx/

npx comes with npm (since version 5.2). If you don't have npm installed already, do it now from https://nodejs.org (npm is installed with Node).

If you are unsure which version of npm you have, run npm -v to check if you need to update.

Tip: check out my OSX terminal tutorial at https://flaviocopes.com/macos-terminal/ if you're unfamiliar with using the terminal. It applies to Mac and Linux.

When you run npx create-react-app <app-name>, npx is going to download the most recent create-react-app release, run it, and then remove it from your system.

This is great because you will never have an outdated version on your system, and every time you run it, you're getting the latest and greatest code available.

Let's start then:

npx create-react-app todolist

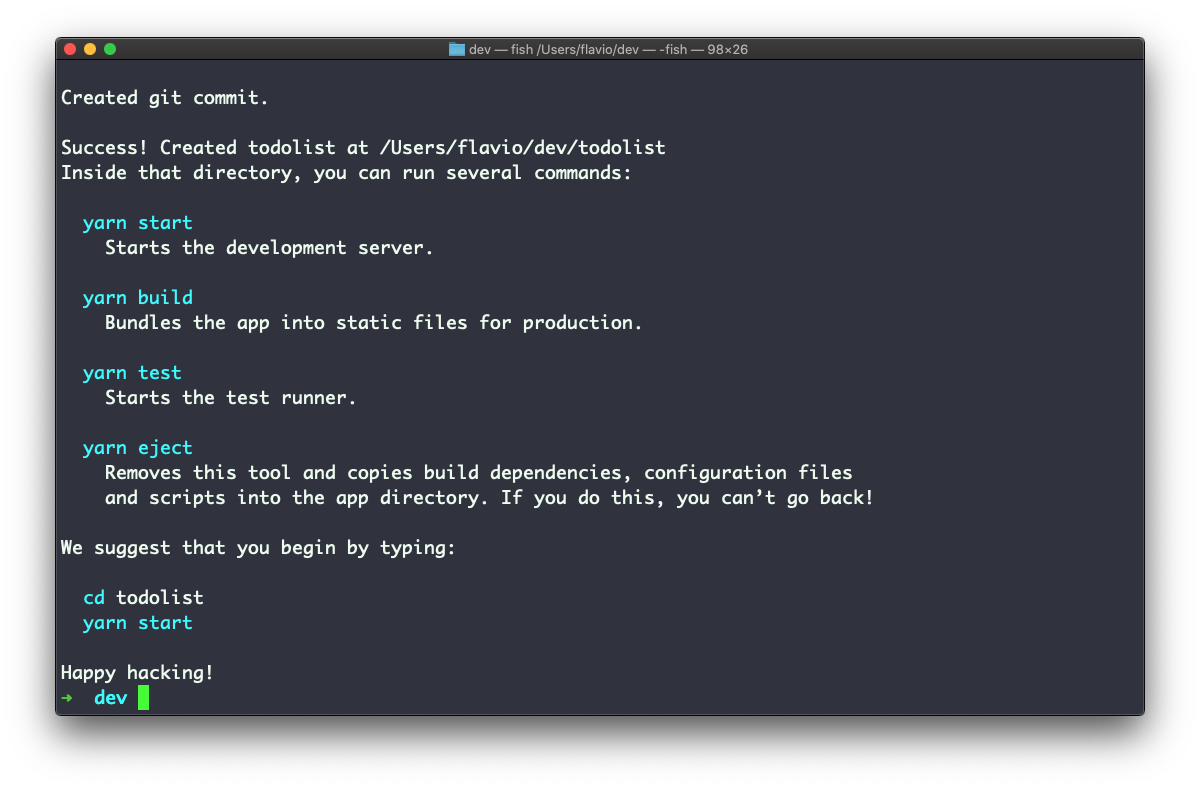

This is when it finished running:

create-react-app created a file structure in the folder you told it to (todolist in this case), and initialized a Git repository.

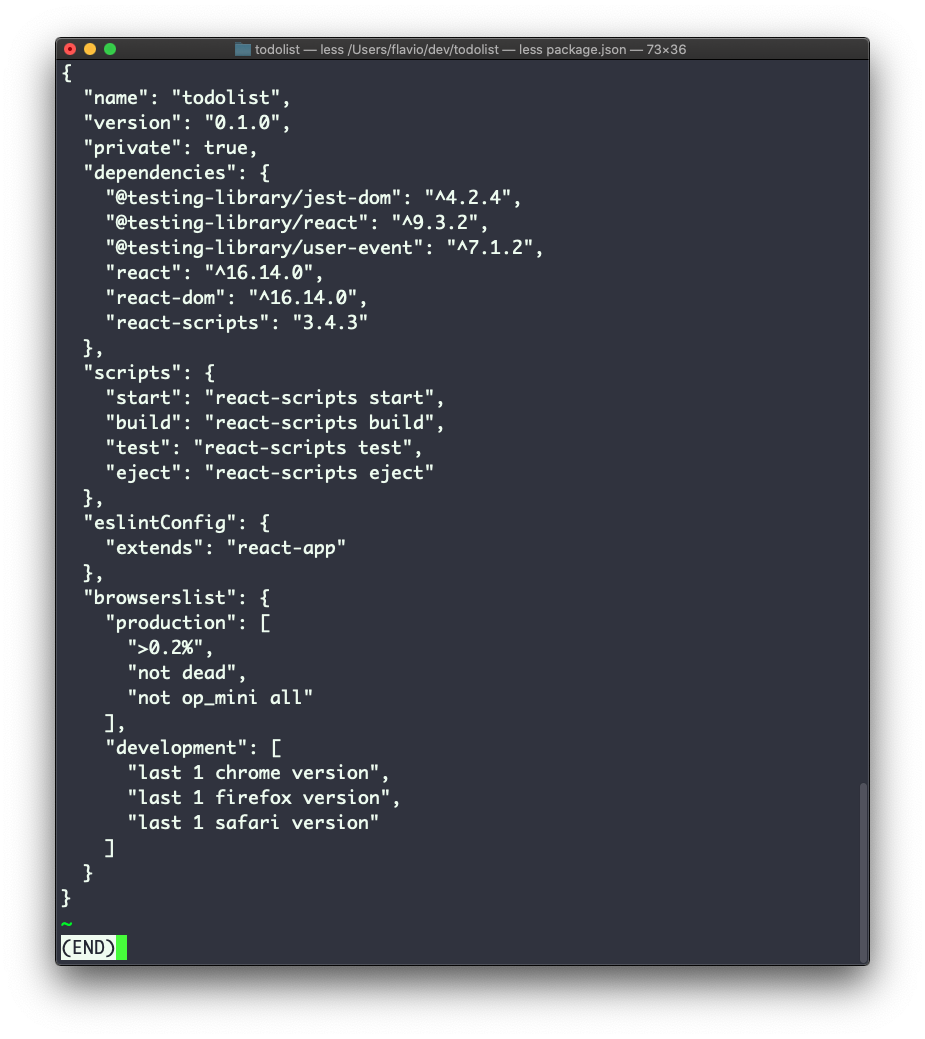

It also added a few commands in the package.json file:

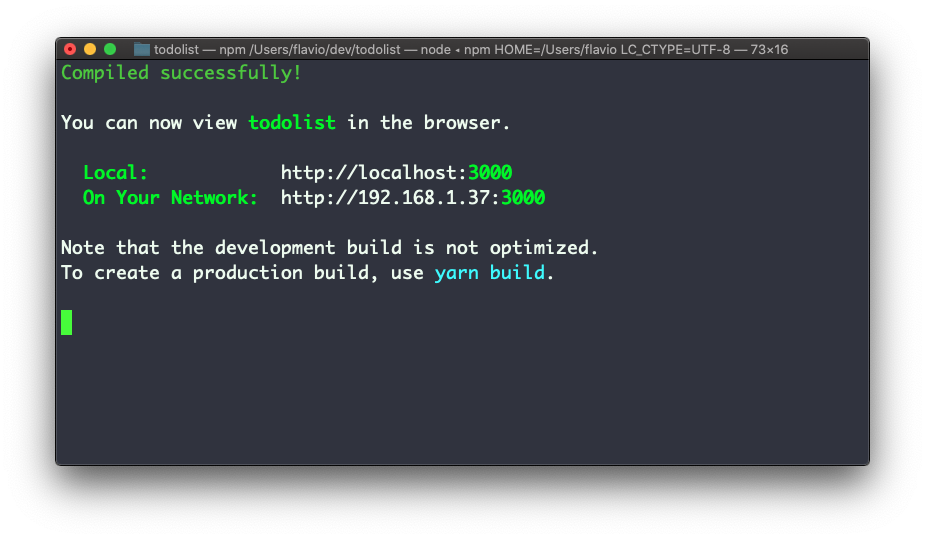

So you can immediately start the app by going into the newly created application folder and running npm start.

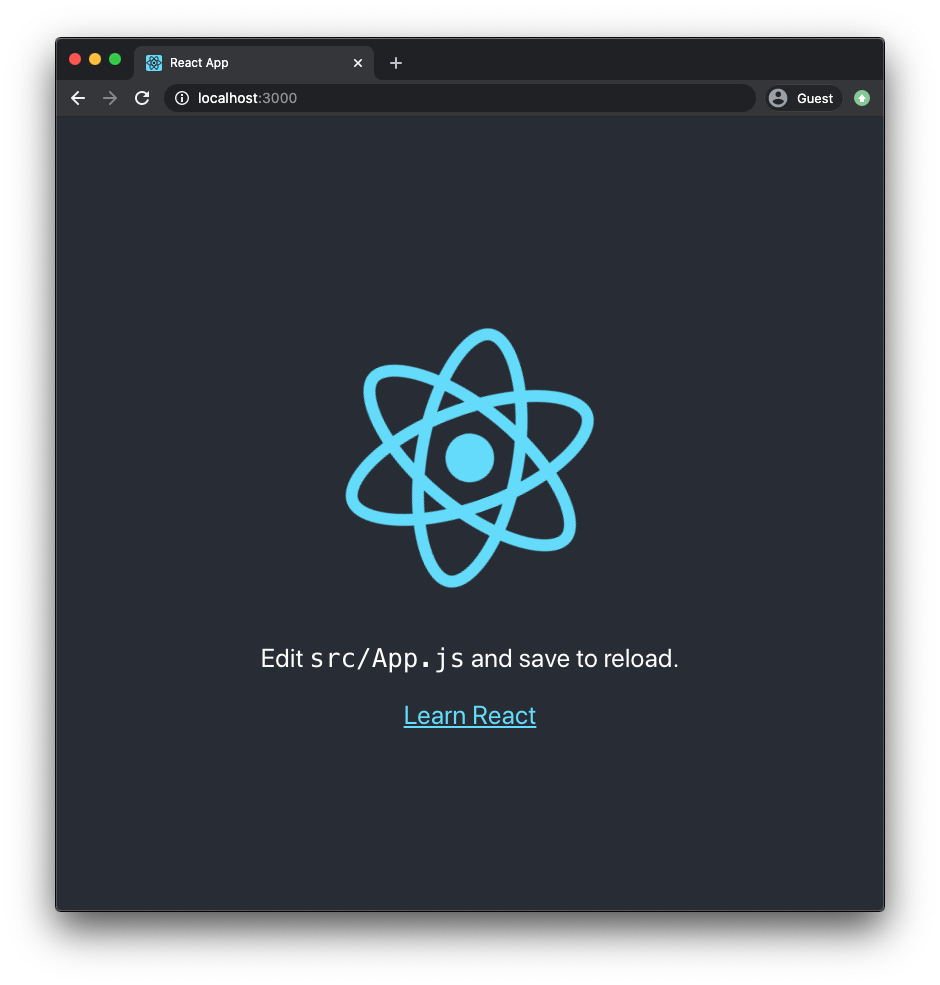

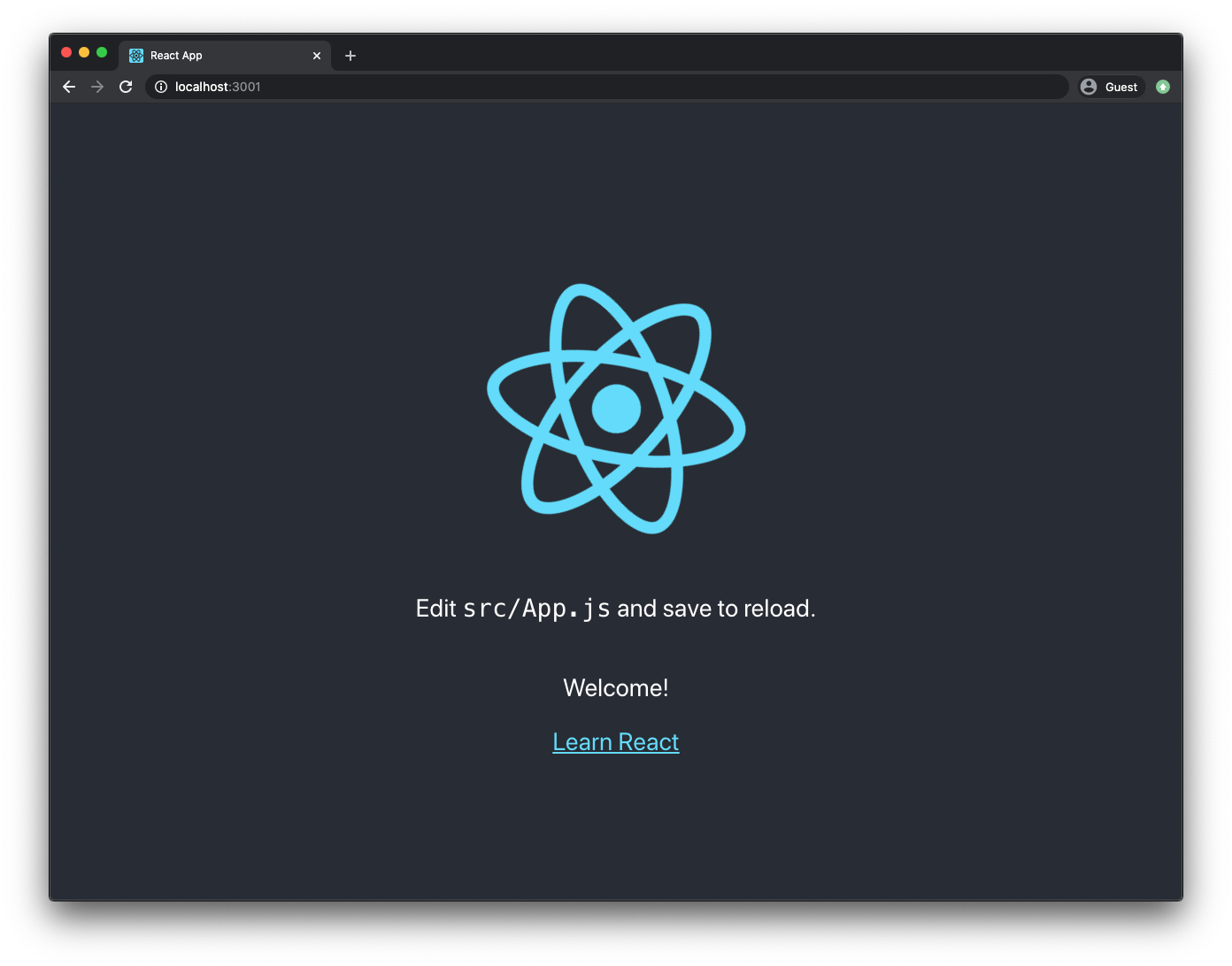

By default this command launches the app on your local port 3000, and it opens your browser showing you the welcome screen:

Now you're ready to work on this application!

React Components

In the last section you saw how to create your first React application.

This application comes with a series of files that do various things, mostly related to configuration, but there's one file that stands out: App.js.

App.js is the first React Component you meet.

Its code is this:

import React from 'react'

import logo from './logo.svg'

import './App.css'

function App() {

return (

<div className="App">

<header className="App-header">

<img src={logo} className="App-logo" alt="logo" />

<p>

Edit <code>src/App.js</code> and save to reload.

</p>

<a

className="App-link"

href="https://reactjs.org"

target="_blank"

rel="noopener noreferrer"

>

Learn React

</a>

</header>

</div>

)

}

export default App

An application built using React, or one of the other popular frontend frameworks like Vue and Svelte for example, is built using dozens of components.

But let's start by analyzing this first component. I'm going to simplify this component code like this:

import React from 'react'

import logo from './logo.svg'

import './App.css'

function App() {

return /* something */

}

export default App

You can see a few things here. We import some things, and we export a function called App.

The things we import in this case are a JavaScript library (the react npm package), an SVG image, and a CSS file.

create-react-appis set up in a way that allows us to import images and CSS to use in our JavaScript, but this is not something you need to care about now. What you need to care about is the concept of a component

App is a function that, in the original example, returns something that at first sight looks quite strange.

It looks like HTML but it has some JavaScript embedded into it.

That is JSX, a special language we use to build a component's output. We'll talk more about JSX in the next section.

In addition to defining some JSX to return, a component has several other characteristics.

A component can have its own state, which means it encapsulates some variables that other components can't access unless this component exposes this state to the rest of the application.

A component can also receive data from other components. In this case we're talking about props.

Don't worry, we're going to look in detail at all those terms (JSX, State and Props) soon.

Introduction to JSX

We can't talk about React without first explaining JSX.

In the last section you met your first React component, the App component defined in the default application built by create-react-app.

Its code was this:

import React from 'react'

import logo from './logo.svg'

import './App.css'

function App() {

return (

<div className="App">

<header className="App-header">

<img src={logo} className="App-logo" alt="logo" />

<p>

Edit <code>src/App.js</code> and save to reload.

</p>

<a

className="App-link"

href="https://reactjs.org"

target="_blank"

rel="noopener noreferrer"

>

Learn React

</a>

</header>

</div>

)

}

export default App

We previously ignored everything that was inside the return statement, but in this section we're going to talk about it.

We call JSX everything wrapped inside the parentheses returned by the component:

<div className="App">

<header className="App-header">

<img src={logo} className="App-logo" alt="logo" />

<p>

Edit <code>src/App.js</code> and save to reload.

</p>

<a

className="App-link"

href="https://reactjs.org"

target="_blank"

rel="noopener noreferrer"

>

Learn React

</a>

</header>

</div>

This looks like HTML, but it's not really HTML. It's a little different.

And it's a bit strange to have this code inside a JavaScript file. This does not look like JavaScript at all!

Under the hood, React will process the JSX and it will transform it into JavaScript that the browser will be able to interpret.

So we're writing JSX, but in the end there's a translation step that makes it digestible to a JavaScript interpreter.

React gives us this interface for one reason: it's easier to build UI interfaces using JSX.

Once you get more familiar with it, of course.

In the next section we'll talk about how JSX lets you easily compose a UI, then we'll look at the differences with "normal HTML" that you need to know.

Using JSX to compose a UI

As introduced in the last section, one of the main benefits of JSX is that it makes it very easy to build a UI.

In particular, in a React component you can import other React components, and you can embed them and display them.

A React component is usually created in its own file, because that's how we can easily reuse it (by importing it) in other components.

But a React component can also be created in the same file of another component, if you plan to only use it in that component. There's no "rule" here, you can do what feels best to you.

I generally use separate files when the number of lines in a file grows too much.

To keep things simple let's create a component in the same App.js file.

We're going to create a WelcomeMessage component:

function WelcomeMessage() {

return <p>Welcome!</p>

}

See? It's a simple function that returns a line of JSX that represents a p HTML element.

We're going to add it to the App.js file.

Now inside the App component JSX we can add <WelcomeMessage /> to show this component in the user interface:

import React from 'react'

import logo from './logo.svg'

import './App.css'

function WelcomeMessage() {

return <p>Welcome!</p>

}

function App() {

return (

<div className="App">

<header className="App-header">

<img src={logo} className="App-logo" alt="logo" />

<p>

Edit <code>src/App.js</code> and save to reload.

</p>

<WelcomeMessage />

<a

className="App-link"

href="https://reactjs.org"

target="_blank"

rel="noopener noreferrer"

>

Learn React

</a>

</header>

</div>

)

}

export default App

And here's the result. Can you see the "Welcome!" message in the screen?

We say that WelcomeMessage is a child component of App, and App is its parent componnet.

We're adding the <WelcomeMessage /> component as if it was part of the HTML language.

That's the beauty of React components and JSX: we can compose an application interface and use it like we're writing HTML.

With some differences, as we'll see in the next section.

The difference between JSX and HTML

JSX kind of looks like HTML, but it's not.

In this section I want to introduce you to some of the most important things you need to keep in mind when using JSX.

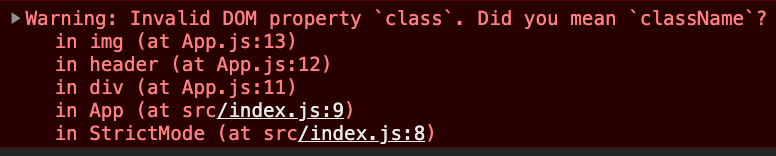

One of the differences might be quite obvious if you looked at the App component JSX: there's a strange attribute called className.

In HTML we use the class attribute. It's probably the most widely used attribute, for various reasons. One of those reasons is CSS. The class attribute allows us to style HTML elements easily, and CSS frameworks like Tailwind put this attribute to the center of the CSS user interface design process.

But there's a problem. We are writing this UI code in a JavaScript file, and class in the JavaScript programming language is a reserved word. This means we can't use this reserved word as we want. It serves a specific purpose (defining JavaScript classes) and the React creators had to choose a different name for it.

That's how we ended up with className instead of class.

You need to remember this especially when you're copy/pasting some existing HTML.

React will try its best to make sure things don't break, but it will raise a lot of warnings in the Developer Tools:

This is not the only HTML feature that suffers from this problem, but it's the most common one.

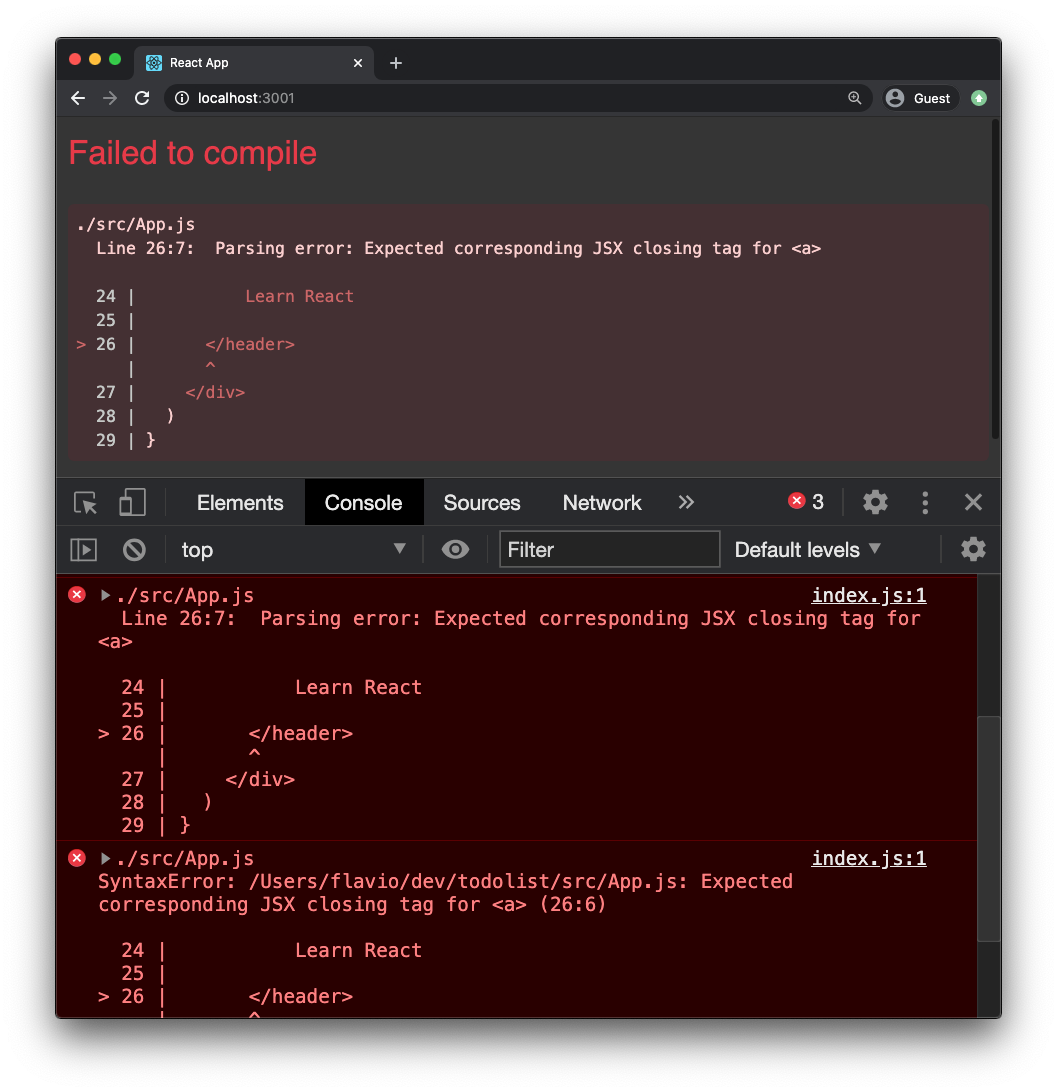

Another big difference between JSX and HTML is that HTML is very relaxed, we can say. Even if you have an error in the syntax, or you close the wrong tag, or you have a mismatch, the browser will try its best to interpret the HTML without breaking.

It's one of the core features of the Web. It is very forgiving.

JSX is not forgiving. If you forget to close a tag, you will have a clear error message:

React usually gives very good and informative error messages that point you in the right direction to fix the problem.

Another big difference between JSX and HTML is that in JSX we can embed JavaScript.

Let's talk about this in the next section.

Embedding JavaScript in JSX

One of the best features of React is that we can easily embed JavaScript into JSX.

Other frontend frameworks, for example Angular and Vue, have their own specific ways to print JavaScript values in the template, or perform things like loops.

React doesn't add new things. Instead, it lets us use JavaScript in the JSX, by using curly brackets.

The first example of this that I will show you comes directly from the App component we've studied so far.

We import the logo SVG file using

import logo from './logo.svg'

and then in the JSX we assign this SVG file to the src attribute of an img tag:

<img src={logo} className="App-logo" alt="logo" />

Let's do another example. Suppose the App component has a variable called message:

function App() {

const message = 'Hello!'

//...

}

We can print this value in the JSX by adding {message} anywhere in the JSX.

Inside the curly brackets { } we can add any JavaScript statement, but just one statement for every curly bracket block.

And the statement must return something.

For example this is a common statement you will find in JSX. We have a ternary operator where we define a condition (message === 'Hello!'), and we print one value if the condition is true, or another value (the content of message in this case) if the condition is false:

{

message === 'Hello!' ? 'The message was "Hello!"' : message

}

Managing state in React

Every React component can have its own state.

What do we mean by state? The state is the set of data that is managed by the component.

Think about a form, for example. Each individual input element of the form is responsible for managing its state: what is written inside it.

A button is responsible for knowing if it's being clicked, or not. If it's on focus.

A link is responsible for knowing if the mouse is hovering over it.

In React, or in any other components-based framework/library, all our applications are based on and make heavy use of components' state.

We manage state using the useState utility provided by React. It's technically a hook (you don't need to know the details of hooks right now, but that's what it is).

You import useState from React in this way:

import React, { useState } from 'react'

Calling useState(), you will get back a new state variable, and a function that we can call to alter its value.

useState() accepts the initial value of the state item and returns an array containing the state variable, and the function you call to alter the state.

Example:

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

This is important. We can't just alter the value of a state variable directly. We must call its modifier function. Otherwise the React component will not update its UI to reflect the changes of the data.

Calling the modifier is the way we can tell React that the component state has changed.

The syntax is a bit weird, right? Since useState() returns an array we use array destructuring to access each individual item, like this: const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

Here's a practical example:

import { useState } from 'react'

const Counter = () => {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

return (

<div>

<p>You clicked {count} times</p>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>Click me</button>

</div>

)

}

ReactDOM.render(<Counter />, document.getElementById('app'))

You can add as many useState() calls as you want, to create as many state variables as you want:

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

const [anotherCounter, setAnotherCounter] = useState(0)

Component Props in React

We call props the initial values passed to a component.

We previously created a WelcomeMessage component

function WelcomeMessage() {

return <p>Welcome!</p>

}

and we used it like this:

<WelcomeMessage />

This component does not have any initial value. It does not have props.

Props can be passed as attributes to the component in the JSX:

<WelcomeMessage myprop={'somevalue'} />

and inside the component we receive the props as arguments:

function WelcomeMessage(props) {

return <p>Welcome!</p>

}

It's common to use object destructuring to get the props by name:

function WelcomeMessage({ myprop }) {

return <p>Welcome!</p>

}

Now that we have the prop, we can use it inside the component. For example we can print its value in the JSX:

function WelcomeMessage({ myprop }) {

return <p>{myprop}</p>

}

Curly brackets here have various meanings. In the case of the function argument, curly brackets are used as part of the object destructuring syntax.

Then we use them to define the function code block, and finally in the JSX to print the JavaScript value.

Passing props to components is a great way to pass values around in your application.

A component either holds data (has state) or receives data through its props.

We can also send functions as props, so a child component can call a function in the parent component.

A special prop is called children. That contains the value of anything that is passed between the opening and closing tags of the component, for example:

<WelcomeMessage> Here is some message </WelcomeMessage>

In this case, inside WelcomeMessage we could access the value Here is some message by using the children prop:

function WelcomeMessage({ children }) {

return <p>{children}</p>

}

Data flow in a React application

In a React application, data typically flows from a parent component to a child component, using props as we saw in the previous section:

<WelcomeMessage myprop={'somevalue'} />

If you pass a function to the child component, you can however change the state of the parent component from a child component:

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

<Counter setCount={setCount} />

Inside the Counter component we can now grab the setCount prop and call it to update the count state in the parent component, when something happens:

function Counter({ setCount }) {

//...

setCount(1)

//...

}

You need to know that there are more advanced ways to manage data, which include the Context API and libraries like Redux. But those introduce more complexity, and 90% of the times using those 2 ways I just explained are the perfect solution.

Handling user events in React

React provides an easy way to manage events fired from DOM events like clicks, form events, and more.

Let's talk about click events, which are pretty simple to digest.

You can use the onClick attribute on any JSX element:

<button

onClick={(event) => {

/* handle the event */

}}

>

Click here

</button>

When the element is clicked, the function passed to the onClick attribute is fired.

You can define this function outside of the JSX:

const handleClickEvent = (event) => {

/* handle the event */

}

function App() {

return <button onClick={handleClickEvent}>Click here</button>

}

When the click event is fired on the button, React calls the event handler function.

React supports a vast amount of types of events, like onKeyUp, onFocus,onChange, onMouseDown, onSubmit and many more.

Lifecycle events in a React component

So far we've seen how to manage state with the useState hook.

There's another hook I want to introduce in this book: useEffect.

The useEffect hook allows components to have access to the lifecycle events of a component.

When you call the hook, you pass it a function. The function will be run by React when the component is first rendered, and on every subsequent re-render/update.

React first updates the DOM, then calls any function passed to useEffect().

All without blocking the UI rendering, even on blocking code.

Here is an example:

const { useEffect, useState } = React

const CounterWithNameAndSideEffect = () => {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

useEffect(() => {

console.log(`You clicked ${count} times`)

})

return (

<div>

<p>You clicked {count} times</p>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>Click me</button>

</div>

)

}

Since the useEffect() function is run on every subsequent re-render/update of the component, we can tell React to skip it, for performance purposes. We do this by adding a second parameter which is an array that contains a list of state variables to watch for.

React will only re-run the side effect if one of the items in this array changes.

useEffect(() => {

console.log(`Hi ${name} you clicked ${count} times`)

}, [name, count])

Similarly, you can tell React to only execute the side effect once (at mount time), by passing an empty array:

useEffect(() => {

console.log(`Component mounted`)

}, [])

You migth find yourself using this option a lot.

useEffect() is great for adding logs, accessing 3rd party APIs, and much more.

Where to go from here

Mastering the topics explained in this article is a great step towards your goal of learning React.

I want to give you some pointers now, because it's easy to get lost in the sea of tutorials and courses about React.

What should you learn next?

Learn more theory about the Virtual DOM, writing declarative code, unidirectional data flow, immutability, composition.

Start building some simple React applications. For example build a simple counter or a interact with a public API.

Learn how to perform conditional rendering, how to perform loops in JSX, how to use the React Developer Tools.

Learn how to apply CSS in a React application, with plain CSS or Styled Components.

Learn how to manage state using the Context API, useContext and Redux.

Learn how to interact with forms.

Learn how to use React Router.

Learn how to test React applications.

Learn an application framework built on top of React, like Gatsby or Next.js.

Most of all, make sure you practice by building sample applications to apply everything you've learned.

Conclusion

Thanks a lot for reading this handbook.

I hope it will inspire you to learn more about React and everything you can do with it!

Remember that you can download this handbook in PDF / ePub / Mobi format for free if you want.

I publish programming tutorials every day on my website flaviocopes.com if you want to check out more great content like this.

You can reach me on Twitter @flaviocopes.