By Jean-Marc Möckel

I've created and consumed many API's over the past few years. During that time, I've come across good and bad practices and have experienced nasty situations when consuming and building API's. But there also have been great moments.

There are helpful articles online which present many best practices, but many of them lack some practicality in my opinion. Knowing the theory with few examples is good, but I've always wondered how the implementation would look in a more real world example.

Providing simple examples helps to understand the concept itself without a lot of complexity, but in practice things aren't always so simple. I'm pretty sure you know what I'm talking about 😁

That's why I've decided to write this tutorial. I've merged all those learnings (good and bad) together into one digestible article while providing a practical example that can be followed along. In the end, we'll build a full API while we're implementing one best practice after another.

A few things to remember before we start off:

Best practices are, as you might have guessed, not specific laws or rules to follow. They are conventions or tips that have evolved over time and turned out to be effective. Some have became standard nowadays. But this doesn't mean you have to adapt them 1:1.

They should give you a direction to make your API's better in terms of user experience (for the consumer and the builder), security, and performance.

Just keep in mind that projects are different and require different approaches. There might be situations where you can't or shouldn't follow a certain convention. So every engineer has to decide this for themselves or with their.

Now that we've got those things out of our way, without further ado let's get to work!

Table of Contents

- Our Example Project

- REST API Best Practices

- Versioning

- Name resources in plural

- Accept and respond with data in JSON format

- Respond with standard HTTP Error Codes

- Avoid verbs in endpoint names

- Group associated resources together

- Integrate filtering, sorting & pagination

- Use data caching for performance improvements

- Good security practices

- Document your API properly

- Conclusion

Our Example Project

_Photo by [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com/@alvarordesign?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditCopyText">Alvaro Reyes on <a href="https://unsplash.com/s/photos/project?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utmcontent=creditCopyText)

_Photo by [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com/@alvarordesign?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditCopyText">Alvaro Reyes on <a href="https://unsplash.com/s/photos/project?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utmcontent=creditCopyText)

Before we start implementing the best practices into our example project, I'd like to give you a brief introduction to what we'll be building.

We'll build a REST API for a CrossFit Training Application. If you're not familiar with CrossFit, it's a fitness method and competitive sport that combines high-intensity workouts with elements from several sports (olympic weightlifting, gymnastics, and others).

In our application we'd like to create, read, update and delete WOD's (Workouts of the Day). This will help our users (that will be gym owners) come up with workout plans and maintain their own workouts inside a single application. On top of that, they also can add some important training tips for each workout.

Our job will require us to design and implement an API for that application.

Prerequisites

In order to follow along you need to have some experience in JavaScript, Node.js, Express.js and in Backend Architecture. Terms like REST and API shouldn't be new to you and you should have an understanding of the Client-Server-Model.

Of course you don't have to be an expert in those topics, but familiarity and ideally some experience should be enough.

If not all prerequisites apply to you, it's of course not a reason to skip this tutorial. There's still a lot to learn here for you as well. But having those skills will make it easier for you to follow along.

Even though this API is written in JavaScript and Express, the best practices are not limited to these tools. They can be applied to other programming languages or frameworks as well.

Architecture

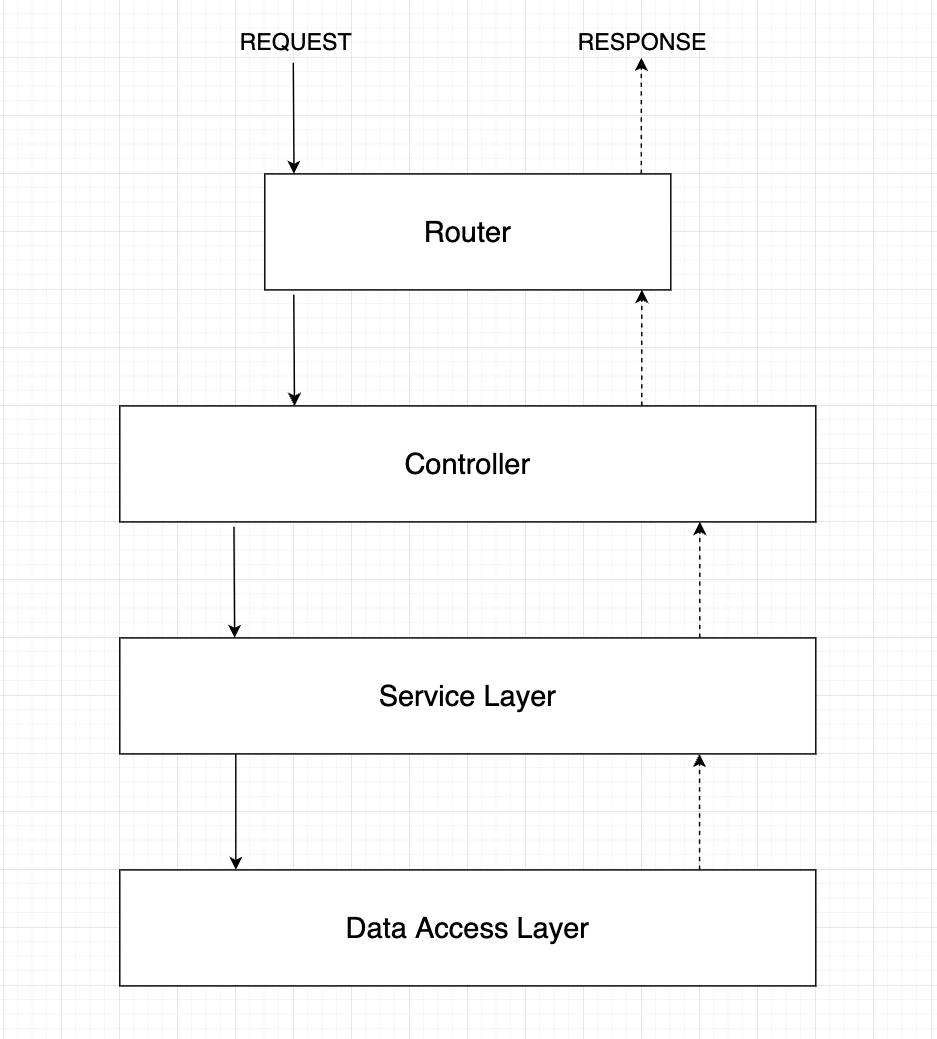

As discussed above, we'll be using Express.js for our API. I don't want to come up with a complex architecture so I'd like to stick to the 3 Layer Architecture:

Inside the Controller we'll be handling all stuff that is related to HTTP. That means we're dealing with requests and responses for our endpoints. Above that layer is also a little Router from Express that passes requests to the corresponding controller.

The whole business logic will be in the Service Layer that exports certain services (methods) which are used by the controller.

The third layer is the Data Access Layer where we'll be working with our Database. We'll be exporting some methods for certain database operations like creating a WOD that can be used by our Service Layer.

In our example we're not using a real database such as MongoDB or PostgreSQL because I'd like to focus more on the best practices itself. Therefore we're using a local JSON file that mimics our Database. But this logic can be transferred to other databases of course.

Basic Setup

Now we should be ready to create a basic setup for our API. We won't overcomplicate things, and we'll build a simple but organized project structure.

First, let's create the overall folder structure with all necessary files and dependencies. After that, we'll make a quick test to check if everything is running properly:

# Create project folder & navigate into it

mkdir crossfit-wod-api && cd crossfit-wod-api

# Create a src folder & navigate into it

mkdir src && cd src

# Create sub folders

mkdir controllers && mkdir services && mkdir database && mkdir routes

# Create an index file (entry point of our API)

touch index.js

# We're currently in the src folder, so we need to move one level up first

cd ..

# Create package.json file

npm init -y

Install dependencies for the basic setup:

# Dev Dependencies

npm i -D nodemon

# Dependencies

npm i express

Open the project up in your favorite Text Editor and configure Express:

// In src/index.js

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

const PORT = process.env.PORT || 3000;

// For testing purposes

app.get("/", (req, res) => {

res.send("<h2>It's Working!</h2>");

});

app.listen(PORT, () => {

console.log(`API is listening on port ${PORT}`);

});

Integrate a new script called "dev" inside package.json:

{

"name": "crossfit-wod-api",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "",

"main": "index.js",

"scripts": {

"dev": "nodemon src/index.js"

},

"keywords": [],

"author": "",

"license": "ISC",

"devDependencies": {

"nodemon": "^2.0.15"

},

"dependencies": {

"express": "^4.17.3"

}

}

The script makes sure that the development server restarts automatically when we make changes (thanks to nodemon).

Spin up the development server:

npm run dev

Look at your terminal, and there should be a message that the "API is listening on port 3000".

Visit localhost:3000 inside your browser. When everything is setup correctly, you should see the following:

Great! We're all set up now to implement the best practices.

REST API Best Practices

_Photo by [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com/@conniwenningsimages?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditCopyText">Constantin Wenning on <a href="https://unsplash.com/s/photos/handshake?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utmcontent=creditCopyText)

_Photo by [Unsplash](https://unsplash.com/@conniwenningsimages?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditCopyText">Constantin Wenning on <a href="https://unsplash.com/s/photos/handshake?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utmcontent=creditCopyText)

Yeah! Now that we have a really basic Express setup, we can extend our API with the following best practices.

Let's start simple with our fundamental CRUD endpoints. After that we'll be extending the API with each best practice.

Versioning

Wait a second. Before we write any API-specific code we should be aware of versioning. Like in other applications there will be improvements, new features, and stuff like that. So it's important to version our API as well.

The big advantage is that we can work on new features or improvements on a new version while the clients are still using the current version and are not affected by breaking changes.

We also don't force the clients to use the new version straight away. They can use the current version and migrate on their own when the new version is stable.

The current and new versions are basically running in parallel and don't affect each other.

But how can we differentiate between the versions? One good practice is to add a path segment like v1 or v2 into the URL.

// Version 1

"/api/v1/workouts"

// Version 2

"/api/v2/workouts"

// ...

That's what we expose to the outside world and what can be consumed by other developers. But we also need to structure our project in order to differentiate between each version.

There are many different approaches to handling versioning inside an Express API. In our case I'd like to create a sub folder for each version inside our src directory called v1.

mkdir src/v1

Now we move our routes folder into that new v1 directory.

# Get the path to your current directory (copy it)

pwd

# Move "routes" into "v1" (insert the path from above into {pwd})

mv {pwd}/src/routes {pwd}/src/v1

The new directory /src/v1/routes will store all our routes for version 1. We will add "real" content later on. But for now let's add a simple index.js file to test things out.

# In /src/v1/routes

touch index.js

Inside there we spin up a simple router.

// In src/v1/routes/index.js

const express = require("express");

const router = express.Router();

router.route("/").get((req, res) => {

res.send(`<h2>Hello from ${req.baseUrl}</h2>`);

});

module.exports = router;

Now we have to hook up our router for v1 inside our root entry point inside src/index.js.

// In src/index.js

const express = require("express");

// *** ADD ***

const v1Router = require("./v1/routes");

const app = express();

const PORT = process.env.PORT || 3000;

// *** REMOVE ***

app.get("/", (req, res) => {

res.send("<h2>It's Working!</h2>");

});

// *** ADD ***

app.use("/api/v1", v1Router);

app.listen(PORT, () => {

console.log(`API is listening on port ${PORT}`);

});

Now visit localhost:3000/api/v1 inside your browser and you should see the following:

Congratulations! You've just structured the project for handling different versions. We are now passing incoming requests with "/api/v1" to our version 1 router, that will route each request to the corresponding controller method later.

Before we move on, I'd like to point something out.

We just moved our routes folder into our v1 directory. The other folders like controllers or services still remain inside our src directory. That is okay for now because we are building a rather small API. We can use the same controllers and services in each version globally.

When the API is growing and requires different controller methods specific for v2, for example, it would be a better idea to move the controllers folder into the v2 directory as well to have all specific logic for that particular version encapsulated.

Another reason for that could be that we might change a service that is used by all other versions. We don't want to break things in the other versions. So it would be a wise decision to move the services folder also into a specific version folder.

But as I said, in our example it's okay for me to only differentiate between the routes and let the router handle the rest. Nonetheless it's important to keep that in mind to have a clear structure when the API scales up and needs changes.

Name Resources in Plural

After setting it all up we can now dive into the real implementation of our API. Like I said, I'd like to start with our fundamental CRUD endpoints.

In other words, let's start implementing endpoints for creating, reading, updating and deleting workouts.

First, let's hook up a specific controller, service, and router for our workouts.

touch src/controllers/workoutController.js

touch src/services/workoutService.js

touch src/v1/routes/workoutRoutes.js

I always like to start with the routes first. Let's think about how we can name our endpoints. This goes hand in hand with this particular best practice.

We could name the creation endpoint /api/v1/workout because we'd like to add one workout, right? Basically there's nothing wrong with that approach – but this can lead to misunderstandings.

Always remember: Your API is used by other humans and should be precise. This goes also for naming your resources.

I always imagine a resource like a box. In our example the box is a collection that stores different workouts.

Naming your resources in plural has the big advantage that it's crystal clear to other humans, that this is a collection that consists of different workouts.

So, let's define our endpoints inside our workout router.

// In src/v1/routes/workoutRoutes.js

const express = require("express");

const router = express.Router();

router.get("/", (req, res) => {

res.send("Get all workouts");

});

router.get("/:workoutId", (req, res) => {

res.send("Get an existing workout");

});

router.post("/", (req, res) => {

res.send("Create a new workout");

});

router.patch("/:workoutId", (req, res) => {

res.send("Update an existing workout");

});

router.delete("/:workoutId", (req, res) => {

res.send("Delete an existing workout");

});

module.exports = router;

You can delete our test file index.js inside src/v1/routes.

Now let's jump into our entry point and hook up our v1 workout router.

// In src/index.js

const express = require("express");

// *** REMOVE ***

const v1Router = require("./v1/routes");

// *** ADD ***

const v1WorkoutRouter = require("./v1/routes/workoutRoutes");

const app = express();

const PORT = process.env.PORT || 3000;

// *** REMOVE ***

app.use("/api/v1", v1Router);

// *** ADD ***

app.use("/api/v1/workouts", v1WorkoutRouter);

app.listen(PORT, () => {

console.log(`API is listening on port ${PORT}`);

});

That went smoothly, right? Now we're catching all requests that are going to /api/v1/workouts with our v1WorkoutRouter.

Inside our router we will call a different method handled by our controller for each different endpoint.

Let's create a method for each endpoint. Just sending a message back should be fine for now.

// In src/controllers/workoutController.js

const getAllWorkouts = (req, res) => {

res.send("Get all workouts");

};

const getOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

res.send("Get an existing workout");

};

const createNewWorkout = (req, res) => {

res.send("Create a new workout");

};

const updateOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

res.send("Update an existing workout");

};

const deleteOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

res.send("Delete an existing workout");

};

module.exports = {

getAllWorkouts,

getOneWorkout,

createNewWorkout,

updateOneWorkout,

deleteOneWorkout,

};

Now it's time to refactor our workout router a bit and use the controller methods.

// In src/v1/routes/workoutRoutes.js

const express = require("express");

const workoutController = require("../../controllers/workoutController");

const router = express.Router();

router.get("/", workoutController.getAllWorkouts);

router.get("/:workoutId", workoutController.getOneWorkout);

router.post("/", workoutController.createNewWorkout);

router.patch("/:workoutId", workoutController.updateOneWorkout);

router.delete("/:workoutId", workoutController.deleteOneWorkout);

module.exports = router;

Now we can test our GET /api/v1/workouts/:workoutId endpoint by typing localhost:3000/api/v1/workouts/2342 inside the browser. You should see something like this:

We've made it! The first layer of our architecture is done. Let's create our service layer by implementing the next best practice.

Accept and respond with data in JSON format

When interacting with an API, you always send specific data with your request or you receive data with the response. There are many different data formats but JSON (Javascript Object Notation) is a standardized format.

Although there's the term JavaScript in JSON, it's not tied to it specifically. You can also write your API with Java or Python that can handle JSON as well.

Because of its standardization, API's should accept and respond with data in JSON format.

Let's take a look at our current implementation and see how we can integrate this best practice.

First, we create our service layer.

// In src/services/workoutService.js

const getAllWorkouts = () => {

return;

};

const getOneWorkout = () => {

return;

};

const createNewWorkout = () => {

return;

};

const updateOneWorkout = () => {

return;

};

const deleteOneWorkout = () => {

return;

};

module.exports = {

getAllWorkouts,

getOneWorkout,

createNewWorkout,

updateOneWorkout,

deleteOneWorkout,

};

It's also a good practice to name the service methods the same as the controller methods so that you have a connection between those. Let's start off with just returning nothing.

Inside our workout controller we can use these methods.

// In src/controllers/workoutController.js

// *** ADD ***

const workoutService = require("../services/workoutService");

const getAllWorkouts = (req, res) => {

// *** ADD ***

const allWorkouts = workoutService.getAllWorkouts();

res.send("Get all workouts");

};

const getOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

// *** ADD ***

const workout = workoutService.getOneWorkout();

res.send("Get an existing workout");

};

const createNewWorkout = (req, res) => {

// *** ADD ***

const createdWorkout = workoutService.createNewWorkout();

res.send("Create a new workout");

};

const updateOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

// *** ADD ***

const updatedWorkout = workoutService.updateOneWorkout();

res.send("Update an existing workout");

};

const deleteOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

// *** ADD ***

workoutService.deleteOneWorkout();

res.send("Delete an existing workout");

};

module.exports = {

getAllWorkouts,

getOneWorkout,

createNewWorkout,

updateOneWorkout,

deleteOneWorkout,

};

At the moment nothing should have changed inside our responses. But under the hood our controller layer talks now with our service layer.

Inside our service methods we'll be handling our business logic like transforming data structures and communicating with our Database Layer.

To do that, we need a database and a collection of methods that actually handle the database interaction. Our database will be a simple JSON file that is pre-filled with some workouts already.

# Create a new file called db.json inside src/database

touch src/database/db.json

# Create a Workout File that stores all workout specific methods in /src/database

touch src/database/Workout.js

Copy the following into db.json:

{

"workouts": [

{

"id": "61dbae02-c147-4e28-863c-db7bd402b2d6",

"name": "Tommy V",

"mode": "For Time",

"equipment": [

"barbell",

"rope"

],

"exercises": [

"21 thrusters",

"12 rope climbs, 15 ft",

"15 thrusters",

"9 rope climbs, 15 ft",

"9 thrusters",

"6 rope climbs, 15 ft"

],

"createdAt": "4/20/2022, 2:21:56 PM",

"updatedAt": "4/20/2022, 2:21:56 PM",

"trainerTips": [

"Split the 21 thrusters as needed",

"Try to do the 9 and 6 thrusters unbroken",

"RX Weights: 115lb/75lb"

]

},

{

"id": "4a3d9aaa-608c-49a7-a004-66305ad4ab50",

"name": "Dead Push-Ups",

"mode": "AMRAP 10",

"equipment": [

"barbell"

],

"exercises": [

"15 deadlifts",

"15 hand-release push-ups"

],

"createdAt": "1/25/2022, 1:15:44 PM",

"updatedAt": "3/10/2022, 8:21:56 AM",

"trainerTips": [

"Deadlifts are meant to be light and fast",

"Try to aim for unbroken sets",

"RX Weights: 135lb/95lb"

]

},

{

"id": "d8be2362-7b68-4ea4-a1f6-03f8bc4eede7",

"name": "Heavy DT",

"mode": "5 Rounds For Time",

"equipment": [

"barbell",

"rope"

],

"exercises": [

"12 deadlifts",

"9 hang power cleans",

"6 push jerks"

],

"createdAt": "11/20/2021, 5:39:07 PM",

"updatedAt": "11/20/2021, 5:39:07 PM",

"trainerTips": [

"Aim for unbroken push jerks",

"The first three rounds might feel terrible, but stick to it",

"RX Weights: 205lb/145lb"

]

}

]

}

As you can see there are three workouts inserted. One workout consists of an id, name, mode, equipment, exercises, createdAt, updatedAt, and trainerTips.

Let's start with the simplest one and return all workouts that are stored and start with implementing the corresponding method inside our Data Access Layer (src/database/Workout.js).

Again, I've chosen to name the method inside here the same as the one in the service and the controller. But this it totally optional.

// In src/database/Workout.js

const DB = require("./db.json");

const getAllWorkouts = () => {

return DB.workouts;

};

module.exports = { getAllWorkouts };

Jump right back into our workout service and implement the logic for getAllWorkouts.

// In src/database/workoutService.js

// *** ADD ***

const Workout = require("../database/Workout");

const getAllWorkouts = () => {

// *** ADD ***

const allWorkouts = Workout.getAllWorkouts();

// *** ADD ***

return allWorkouts;

};

const getOneWorkout = () => {

return;

};

const createNewWorkout = () => {

return;

};

const updateOneWorkout = () => {

return;

};

const deleteOneWorkout = () => {

return;

};

module.exports = {

getAllWorkouts,

getOneWorkout,

createNewWorkout,

updateOneWorkout,

deleteOneWorkout,

};

Returning all workouts is pretty simple and we don't have to do transformations because it's already a JSON file. We also don't need to take in any arguments for now. So this implementation is pretty straightforward. But we'll come back to this later.

Back in our workout controller we receive the return value from workoutService.getAllWorkouts() and simply send it as a response to the client. We've looped the database response through our service to the controller.

// In src/controllers/workoutControllers.js

const workoutService = require("../services/workoutService");

const getAllWorkouts = (req, res) => {

const allWorkouts = workoutService.getAllWorkouts();

// *** ADD ***

res.send({ status: "OK", data: allWorkouts });

};

const getOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

const workout = workoutService.getOneWorkout();

res.send("Get an existing workout");

};

const createNewWorkout = (req, res) => {

const createdWorkout = workoutService.createNewWorkout();

res.send("Create a new workout");

};

const updateOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

const updatedWorkout = workoutService.updateOneWorkout();

res.send("Update an existing workout");

};

const deleteOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

workoutService.deleteOneWorkout();

res.send("Delete an existing workout");

};

module.exports = {

getAllWorkouts,

getOneWorkout,

createNewWorkout,

updateOneWorkout,

deleteOneWorkout,

};

Go to localhost:3000/api/v1/workouts inside your browser and you should see the response JSON.

That went great! We're sending back data in JSON format. But what about accepting it? Let's think about an endpoint where we need to receive JSON data from the client. The endpoint for creating or updating a workout needs data from the client.

Inside our workout controller we extract the request body for creating a new workout and we pass it on to the workout service. Inside the workout service we'll insert it into our DB.json and send the newly created workout back to the client.

To be able to parse the sent JSON inside the request body, we need to install body-parser first and configure it.

npm i body-parser

// In src/index.js

const express = require("express");

// *** ADD ***

const bodyParser = require("body-parser");

const v1WorkoutRouter = require("./v1/routes/workoutRoutes");

const app = express();

const PORT = process.env.PORT || 3000;

// *** ADD ***

app.use(bodyParser.json());

app.use("/api/v1/workouts", v1WorkoutRouter);

app.listen(PORT, () => {

console.log(`API is listening on port ${PORT}`);

});

Now we're able to receive the JSON data inside our controllers under req.body.

In order to test it properly, just open your favorite HTTP client (I'm using Postman), create a POST request to localhost:3000/api/v1/workouts and a request body in JSON format like this:

{

"name": "Core Buster",

"mode": "AMRAP 20",

"equipment": [

"rack",

"barbell",

"abmat"

],

"exercises": [

"15 toes to bars",

"10 thrusters",

"30 abmat sit-ups"

],

"trainerTips": [

"Split your toes to bars into two sets maximum",

"Go unbroken on the thrusters",

"Take the abmat sit-ups as a chance to normalize your breath"

]

}

As you've might noticed, there are some properties missing like "id", "createdAt" and "updatedAt". That's the job of our API to add those properties before inserting it. We'll take care of it inside our workout service later.

Inside the method createNewWorkout in our workout controller, we can extract the body from the request object, do some validation, and pass it as an argument to our workout service.

// In src/controllers/workoutController.js

...

const createNewWorkout = (req, res) => {

const { body } = req;

// *** ADD ***

if (

!body.name ||

!body.mode ||

!body.equipment ||

!body.exercises ||

!body.trainerTips

) {

return;

}

// *** ADD ***

const newWorkout = {

name: body.name,

mode: body.mode,

equipment: body.equipment,

exercises: body.exercises,

trainerTips: body.trainerTips,

};

// *** ADD ***

const createdWorkout = workoutService.createNewWorkout(newWorkout);

// *** ADD ***

res.status(201).send({ status: "OK", data: createdWorkout });

};

...

To improve the request validation you normally would use a third party package like express-validator.

Let's go into our workout service and receive the data inside our createNewWorkout method.

After that we add the missing properties to the object and pass it to a new method in our Data Access Layer to store it inside our DB.

First, we create a simple Util Function to overwrite our JSON file to persist the data.

# Create a utils file inside our database directory

touch src/database/utils.js

// In src/database/utils.js

const fs = require("fs");

const saveToDatabase = (DB) => {

fs.writeFileSync("./src/database/db.json", JSON.stringify(DB, null, 2), {

encoding: "utf-8",

});

};

module.exports = { saveToDatabase };

Then we can use this function in our Workout.js file.

// In src/database/Workout.js

const DB = require("./db.json");

// *** ADD ***

const { saveToDatabase } = require("./utils");

const getAllWorkouts = () => {

return DB.workouts;

};

// *** ADD ***

const createNewWorkout = (newWorkout) => {

const isAlreadyAdded =

DB.workouts.findIndex((workout) => workout.name === newWorkout.name) > -1;

if (isAlreadyAdded) {

return;

}

DB.workouts.push(newWorkout);

saveToDatabase(DB);

return newWorkout;

};

module.exports = {

getAllWorkouts,

// *** ADD ***

createNewWorkout,

};

That was smooth! The next step is to use the database methods inside our workout service.

# Install the uuid package

npm i uuid

// In src/services/workoutService.js

// *** ADD ***

const { v4: uuid } = require("uuid");

// *** ADD ***

const Workout = require("../database/Workout");

const getAllWorkouts = () => {

const allWorkouts = Workout.getAllWorkouts();

return allWorkouts;

};

const getOneWorkout = () => {

return;

};

const createNewWorkout = (newWorkout) => {

// *** ADD ***

const workoutToInsert = {

...newWorkout,

id: uuid(),

createdAt: new Date().toLocaleString("en-US", { timeZone: "UTC" }),

updatedAt: new Date().toLocaleString("en-US", { timeZone: "UTC" }),

};

// *** ADD ***

const createdWorkout = Workout.createNewWorkout(workoutToInsert);

return createdWorkout;

};

const updateOneWorkout = () => {

return;

};

const deleteOneWorkout = () => {

return;

};

module.exports = {

getAllWorkouts,

getOneWorkout,

createNewWorkout,

updateOneWorkout,

deleteOneWorkout,

};

Wow! This was fun, right? Now you can go to your HTTP client, send the POST request again, and you should receive the newly created workout as JSON.

If you try to add the same workout for a second time, you still receive a 201 status code, but without the newly inserted workout.

This means that our database method cancels the insertion for now and is just returning nothing. That's because our if-statement to check if there is already a workout inserted with the same name kicks in. That's good for now, we'll handle that case in the next best practice!

Now, send a GET request to localhost:3000/api/v1/workouts to read all workouts. I'm choosing the browser for that. You should see that our workout got successfully inserted and persisted:

You can implement the other methods by yourself or just copy my implementations.

First, the workout controller (you can just copy the whole content):

// In src/controllers/workoutController.js

const workoutService = require("../services/workoutService");

const getAllWorkouts = (req, res) => {

const allWorkouts = workoutService.getAllWorkouts();

res.send({ status: "OK", data: allWorkouts });

};

const getOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

const {

params: { workoutId },

} = req;

if (!workoutId) {

return;

}

const workout = workoutService.getOneWorkout(workoutId);

res.send({ status: "OK", data: workout });

};

const createNewWorkout = (req, res) => {

const { body } = req;

if (

!body.name ||

!body.mode ||

!body.equipment ||

!body.exercises ||

!body.trainerTips

) {

return;

}

const newWorkout = {

name: body.name,

mode: body.mode,

equipment: body.equipment,

exercises: body.exercises,

trainerTips: body.trainerTips,

};

const createdWorkout = workoutService.createNewWorkout(newWorkout);

res.status(201).send({ status: "OK", data: createdWorkout });

};

const updateOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

const {

body,

params: { workoutId },

} = req;

if (!workoutId) {

return;

}

const updatedWorkout = workoutService.updateOneWorkout(workoutId, body);

res.send({ status: "OK", data: updatedWorkout });

};

const deleteOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

const {

params: { workoutId },

} = req;

if (!workoutId) {

return;

}

workoutService.deleteOneWorkout(workoutId);

res.status(204).send({ status: "OK" });

};

module.exports = {

getAllWorkouts,

getOneWorkout,

createNewWorkout,

updateOneWorkout,

deleteOneWorkout,

};

Then, the workout service (you can just copy the whole content):

// In src/services/workoutServices.js

const { v4: uuid } = require("uuid");

const Workout = require("../database/Workout");

const getAllWorkouts = () => {

const allWorkouts = Workout.getAllWorkouts();

return allWorkouts;

};

const getOneWorkout = (workoutId) => {

const workout = Workout.getOneWorkout(workoutId);

return workout;

};

const createNewWorkout = (newWorkout) => {

const workoutToInsert = {

...newWorkout,

id: uuid(),

createdAt: new Date().toLocaleString("en-US", { timeZone: "UTC" }),

updatedAt: new Date().toLocaleString("en-US", { timeZone: "UTC" }),

};

const createdWorkout = Workout.createNewWorkout(workoutToInsert);

return createdWorkout;

};

const updateOneWorkout = (workoutId, changes) => {

const updatedWorkout = Workout.updateOneWorkout(workoutId, changes);

return updatedWorkout;

};

const deleteOneWorkout = (workoutId) => {

Workout.deleteOneWorkout(workoutId);

};

module.exports = {

getAllWorkouts,

getOneWorkout,

createNewWorkout,

updateOneWorkout,

deleteOneWorkout,

};

And finally our database methods inside the Data Access Layer (you can just copy the whole content):

// In src/database/Workout.js

const DB = require("./db.json");

const { saveToDatabase } = require("./utils");

const getAllWorkouts = () => {

return DB.workouts;

};

const getOneWorkout = (workoutId) => {

const workout = DB.workouts.find((workout) => workout.id === workoutId);

if (!workout) {

return;

}

return workout;

};

const createNewWorkout = (newWorkout) => {

const isAlreadyAdded =

DB.workouts.findIndex((workout) => workout.name === newWorkout.name) > -1;

if (isAlreadyAdded) {

return;

}

DB.workouts.push(newWorkout);

saveToDatabase(DB);

return newWorkout;

};

const updateOneWorkout = (workoutId, changes) => {

const indexForUpdate = DB.workouts.findIndex(

(workout) => workout.id === workoutId

);

if (indexForUpdate === -1) {

return;

}

const updatedWorkout = {

...DB.workouts[indexForUpdate],

...changes,

updatedAt: new Date().toLocaleString("en-US", { timeZone: "UTC" }),

};

DB.workouts[indexForUpdate] = updatedWorkout;

saveToDatabase(DB);

return updatedWorkout;

};

const deleteOneWorkout = (workoutId) => {

const indexForDeletion = DB.workouts.findIndex(

(workout) => workout.id === workoutId

);

if (indexForDeletion === -1) {

return;

}

DB.workouts.splice(indexForDeletion, 1);

saveToDatabase(DB);

};

module.exports = {

getAllWorkouts,

createNewWorkout,

getOneWorkout,

updateOneWorkout,

deleteOneWorkout,

};

Great! Let's move on to the next best practice and see how we can handle errors properly.

Respond with standard HTTP Error Codes

We've already came pretty far, but we're not finished yet. Our API has the ability now to handle basic CRUD operations with data storage. That's great, but not really ideal.

Why? Let me explain.

In a perfect world everything works smoothly without any errors. But as you might know, in the real world a lot of errors can happen – either from a human or a technical perspective.

You might probably know that weird feeling when things are working right from the beginning without any errors. This is great and enjoyable, but as developers we're more used to things that are not working properly. 😁

The same goes for our API. We should handle certain cases that might go wrong or throw an error. This will also harden our API.

When something goes wrong (either from the request or inside our API) we send HTTP Error codes back. I've seen and used API's that were returning all the time a 400 error code when a request was buggy without any specific message about WHY this error occurred or what the mistake was. So debugging became a pain.

That's the reason why it's always a good practice to return proper HTTP error codes for different cases. This helps the consumer or the engineer who built the API to identify the problem more easily.

To improve the experience we also can send a quick error message along with the error response. But as I've written in the introduction this isn't always very wise and should be considered by the engineer themself.

For example, returning something like "The username is already signed up" should be well thought out because you're providing information about your users that you should really hide.

In our Crossfit API we will take a look at the creation endpoint and see what errors might arise and how we can handle them. At the end of this tip you'll find again the complete implementation for the other endpoints.

Let's start looking at our createNewWorkout method inside our workout controller:

// In src/controllers/workoutController.js

...

const createNewWorkout = (req, res) => {

const { body } = req;

if (

!body.name ||

!body.mode ||

!body.equipment ||

!body.exercises ||

!body.trainerTips

) {

return;

}

const newWorkout = {

name: body.name,

mode: body.mode,

equipment: body.equipment,

exercises: body.exercises,

trainerTips: body.trainerTips,

};

const createdWorkout = workoutService.createNewWorkout(newWorkout);

res.status(201).send({ status: "OK", data: createdWorkout });

};

...

We already caught the case that the request body is not built up properly and got missing keys that we expect.

This would be a good example to send back a 400 HTTP error with a corresponding error message.

// In src/controllers/workoutController.js

...

const createNewWorkout = (req, res) => {

const { body } = req;

if (

!body.name ||

!body.mode ||

!body.equipment ||

!body.exercises ||

!body.trainerTips

) {

res

.status(400)

.send({

status: "FAILED",

data: {

error:

"One of the following keys is missing or is empty in request body: 'name', 'mode', 'equipment', 'exercises', 'trainerTips'",

},

});

return;

}

const newWorkout = {

name: body.name,

mode: body.mode,

equipment: body.equipment,

exercises: body.exercises,

trainerTips: body.trainerTips,

};

const createdWorkout = workoutService.createNewWorkout(newWorkout);

res.status(201).send({ status: "OK", data: createdWorkout });

};

...

If we try to add a new workout but forget to provide the "mode" property in our request body, we should see the error message along with the 400 HTTP error code.

A developer who is consuming the API is now better informed about what to look for. They immediately know to go inside the request body and see if they've missed providing one of the required properties.

Leaving this error message more generic for all properties will be okay for now. Typically you'd use a schema validator for handling that.

Let's go one layer deeper into our workout service and see what potential errors might occur.

// In src/services/workoutService.js

...

const createNewWorkout = (newWorkout) => {

const workoutToInsert = {

...newWorkout,

id: uuid(),

createdAt: new Date().toLocaleString("en-US", { timeZone: "UTC" }),

updatedAt: new Date().toLocaleString("en-US", { timeZone: "UTC" }),

};

const createdWorkout = Workout.createNewWorkout(workoutToInsert);

return createdWorkout;

};

...

One thing that might go wrong is the database insertion Workout.createNewWorkout(). I like to wrap this thing in a try/catch block to catch the error when it occurs.

// In src/services/workoutService.js

...

const createNewWorkout = (newWorkout) => {

const workoutToInsert = {

...newWorkout,

id: uuid(),

createdAt: new Date().toLocaleString("en-US", { timeZone: "UTC" }),

updatedAt: new Date().toLocaleString("en-US", { timeZone: "UTC" }),

};

try {

const createdWorkout = Workout.createNewWorkout(workoutToInsert);

return createdWorkout;

} catch (error) {

throw error;

}

};

...

Every error that gets thrown inside our Workout.createNewWorkout() method will be caught inside our catch block. We're just throwing it back, so we can adjust our responses later inside our controller.

Let's define our errors in Workout.js:

// In src/database/Workout.js

...

const createNewWorkout = (newWorkout) => {

const isAlreadyAdded =

DB.workouts.findIndex((workout) => workout.name === newWorkout.name) > -1;

if (isAlreadyAdded) {

throw {

status: 400,

message: `Workout with the name '${newWorkout.name}' already exists`,

};

}

try {

DB.workouts.push(newWorkout);

saveToDatabase(DB);

return newWorkout;

} catch (error) {

throw { status: 500, message: error?.message || error };

}

};

...

As you can see, an error consists of two things, a status and a message. I'm using just the throw keyword here to send out a different data structure than a string, which is required in throw new Error().

A little downside of just throwing is that we don't get a stack trace. But normally this error throwing would be handled by a third party library of our choice (for example Mongoose if you use a MongoDB database). But for the purposes of this tutorial this should be fine.

Now we're able to throw and catch errors in the service and data access layer. We can move into our workout controller now, catch the errors there as well, and respond accordingly.

// In src/controllers/workoutController.js

...

const createNewWorkout = (req, res) => {

const { body } = req;

if (

!body.name ||

!body.mode ||

!body.equipment ||

!body.exercises ||

!body.trainerTips

) {

res

.status(400)

.send({

status: "FAILED",

data: {

error:

"One of the following keys is missing or is empty in request body: 'name', 'mode', 'equipment', 'exercises', 'trainerTips'",

},

});

return;

}

const newWorkout = {

name: body.name,

mode: body.mode,

equipment: body.equipment,

exercises: body.exercises,

trainerTips: body.trainerTips,

};

// *** ADD ***

try {

const createdWorkout = workoutService.createNewWorkout(newWorkout);

res.status(201).send({ status: "OK", data: createdWorkout });

} catch (error) {

res

.status(error?.status || 500)

.send({ status: "FAILED", data: { error: error?.message || error } });

}

};

...

You can test things out by adding a workout with the same name twice or not providing a required property inside your request body. You should receive the corresponding HTTP error codes along with the error message.

To wrap this up and move to the next tip, you can copy the other implemented methods into the following files or you can try it on your own:

// In src/controllers/workoutController.js

const workoutService = require("../services/workoutService");

const getAllWorkouts = (req, res) => {

try {

const allWorkouts = workoutService.getAllWorkouts();

res.send({ status: "OK", data: allWorkouts });

} catch (error) {

res

.status(error?.status || 500)

.send({ status: "FAILED", data: { error: error?.message || error } });

}

};

const getOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

const {

params: { workoutId },

} = req;

if (!workoutId) {

res

.status(400)

.send({

status: "FAILED",

data: { error: "Parameter ':workoutId' can not be empty" },

});

}

try {

const workout = workoutService.getOneWorkout(workoutId);

res.send({ status: "OK", data: workout });

} catch (error) {

res

.status(error?.status || 500)

.send({ status: "FAILED", data: { error: error?.message || error } });

}

};

const createNewWorkout = (req, res) => {

const { body } = req;

if (

!body.name ||

!body.mode ||

!body.equipment ||

!body.exercises ||

!body.trainerTips

) {

res

.status(400)

.send({

status: "FAILED",

data: {

error:

"One of the following keys is missing or is empty in request body: 'name', 'mode', 'equipment', 'exercises', 'trainerTips'",

},

});

return;

}

const newWorkout = {

name: body.name,

mode: body.mode,

equipment: body.equipment,

exercises: body.exercises,

trainerTips: body.trainerTips,

};

try {

const createdWorkout = workoutService.createNewWorkout(newWorkout);

res.status(201).send({ status: "OK", data: createdWorkout });

} catch (error) {

res

.status(error?.status || 500)

.send({ status: "FAILED", data: { error: error?.message || error } });

}

};

const updateOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

const {

body,

params: { workoutId },

} = req;

if (!workoutId) {

res

.status(400)

.send({

status: "FAILED",

data: { error: "Parameter ':workoutId' can not be empty" },

});

}

try {

const updatedWorkout = workoutService.updateOneWorkout(workoutId, body);

res.send({ status: "OK", data: updatedWorkout });

} catch (error) {

res

.status(error?.status || 500)

.send({ status: "FAILED", data: { error: error?.message || error } });

}

};

const deleteOneWorkout = (req, res) => {

const {

params: { workoutId },

} = req;

if (!workoutId) {

res

.status(400)

.send({

status: "FAILED",

data: { error: "Parameter ':workoutId' can not be empty" },

});

}

try {

workoutService.deleteOneWorkout(workoutId);

res.status(204).send({ status: "OK" });

} catch (error) {

res

.status(error?.status || 500)

.send({ status: "FAILED", data: { error: error?.message || error } });

}

};

module.exports = {

getAllWorkouts,

getOneWorkout,

createNewWorkout,

updateOneWorkout,

deleteOneWorkout,

getRecordsForWorkout,

};

// In src/services/workoutService.js

const { v4: uuid } = require("uuid");

const Workout = require("../database/Workout");

const getAllWorkouts = () => {

try {

const allWorkouts = Workout.getAllWorkouts();

return allWorkouts;

} catch (error) {

throw error;

}

};

const getOneWorkout = (workoutId) => {

try {

const workout = Workout.getOneWorkout(workoutId);

return workout;

} catch (error) {

throw error;

}

};

const createNewWorkout = (newWorkout) => {

const workoutToInsert = {

...newWorkout,

id: uuid(),

createdAt: new Date().toLocaleString("en-US", { timeZone: "UTC" }),

updatedAt: new Date().toLocaleString("en-US", { timeZone: "UTC" }),

};

try {

const createdWorkout = Workout.createNewWorkout(workoutToInsert);

return createdWorkout;

} catch (error) {

throw error;

}

};

const updateOneWorkout = (workoutId, changes) => {

try {

const updatedWorkout = Workout.updateOneWorkout(workoutId, changes);

return updatedWorkout;

} catch (error) {

throw error;

}

};

const deleteOneWorkout = (workoutId) => {

try {

Workout.deleteOneWorkout(workoutId);

} catch (error) {

throw error;

}

};

module.exports = {

getAllWorkouts,

getOneWorkout,

createNewWorkout,

updateOneWorkout,

deleteOneWorkout,

};

// In src/database/Workout.js

const DB = require("./db.json");

const { saveToDatabase } = require("./utils");

const getAllWorkouts = () => {

try {

return DB.workouts;

} catch (error) {

throw { status: 500, message: error };

}

};

const getOneWorkout = (workoutId) => {

try {

const workout = DB.workouts.find((workout) => workout.id === workoutId);

if (!workout) {

throw {

status: 400,

message: `Can't find workout with the id '${workoutId}'`,

};

}

return workout;

} catch (error) {

throw { status: error?.status || 500, message: error?.message || error };

}

};

const createNewWorkout = (newWorkout) => {

try {

const isAlreadyAdded =

DB.workouts.findIndex((workout) => workout.name === newWorkout.name) > -1;

if (isAlreadyAdded) {

throw {

status: 400,

message: `Workout with the name '${newWorkout.name}' already exists`,

};

}

DB.workouts.push(newWorkout);

saveToDatabase(DB);

return newWorkout;

} catch (error) {

throw { status: error?.status || 500, message: error?.message || error };

}

};

const updateOneWorkout = (workoutId, changes) => {

try {

const isAlreadyAdded =

DB.workouts.findIndex((workout) => workout.name === changes.name) > -1;

if (isAlreadyAdded) {

throw {

status: 400,

message: `Workout with the name '${changes.name}' already exists`,

};

}

const indexForUpdate = DB.workouts.findIndex(

(workout) => workout.id === workoutId

);

if (indexForUpdate === -1) {

throw {

status: 400,

message: `Can't find workout with the id '${workoutId}'`,

};

}

const updatedWorkout = {

...DB.workouts[indexForUpdate],

...changes,

updatedAt: new Date().toLocaleString("en-US", { timeZone: "UTC" }),

};

DB.workouts[indexForUpdate] = updatedWorkout;

saveToDatabase(DB);

return updatedWorkout;

} catch (error) {

throw { status: error?.status || 500, message: error?.message || error };

}

};

const deleteOneWorkout = (workoutId) => {

try {

const indexForDeletion = DB.workouts.findIndex(

(workout) => workout.id === workoutId

);

if (indexForDeletion === -1) {

throw {

status: 400,

message: `Can't find workout with the id '${workoutId}'`,

};

}

DB.workouts.splice(indexForDeletion, 1);

saveToDatabase(DB);

} catch (error) {

throw { status: error?.status || 500, message: error?.message || error };

}

};

module.exports = {

getAllWorkouts,

createNewWorkout,

getOneWorkout,

updateOneWorkout,

deleteOneWorkout,

};

Avoid verbs in endpoint names

It doesn't make much sense to use verbs inside your endpoints and is, in fact, pretty useless. Generally each URL should point towards a resource (remember the box example from above). Nothing more and nothing less.

Using a verb inside a URL shows a certain behavior which a resource itself can not have.

We've already implemented the endpoints correctly without using verbs inside the URL, but let's take a look how our URL's would look like if we had used verbs.

// Current implementations (without verbs)

GET "/api/v1/workouts"

GET "/api/v1/workouts/:workoutId"

POST "/api/v1/workouts"

PATCH "/api/v1/workouts/:workoutId"

DELETE "/api/v1/workouts/:workoutId"

// Implementation using verbs

GET "/api/v1/getAllWorkouts"

GET "/api/v1/getWorkoutById/:workoutId"

CREATE "/api/v1/createWorkout"

PATCH "/api/v1/updateWorkout/:workoutId"

DELETE "/api/v1/deleteWorkout/:workoutId"

Do you see the difference? Having a completely different URL for every behavior can become confusing and unnecessarily complex pretty fast.

Imagine we've got 300 different endpoints. Using a separate URL for each one might be an overhead (and documentation) hell.

Another reason I'd like to point out for not using verbs inside your URL is that the HTTP verb itself already indicates the action.

Things like "GET /api/v1/getAllWorkouts" or "DELETE api/v1/deleteWorkout/workoutId" are unnecessary.

When you take a look at our current implementation it becomes way cleaner because we're only using two different URL's and the actual behavior is handled via the HTTP verb and the corresponding request payload.

I always imagine that the HTTP verb describes the action (what we'd like to do) and the URL itself (that points towards a resource) the target. "GET /api/v1/workouts" is also more fluent in human language.

Group associated resources together (logical nesting)

When you're designing your API, there might be cases where you have resources that are associated with others. It's a good practice to group them together into one endpoint and nest them properly.

Let's consider that, in our API, we also have a list of members that are signed up in our CrossFit box ("box" is the name for a CrossFit gym). In order to motivate our members we track the overall box records for each workout.

For example, there is a workout where you have to do a certain order of exercises as quickly as possible. We record the times for all members to have a list of the time for each member who completed this workout.

Now, the frontend needs an endpoint that responds with all records for a specific workout in order to display it in the UI.

The workouts, the members, and the records are stored in different places in the database. So what we need here is a box (records) inside another box (workouts), right?

The URI for that endpoint will be /api/v1/workouts/:workoutId/records. This is a good practice to allow logical nesting of URL's. The URL itself doesn't necessarily have to mirror the database structure.

Let's start implementing that endpoint.

First, add a new table into your db.json called "members". Place it under "workouts".

{

"workouts": [ ...

],

"members": [

{

"id": "12a410bc-849f-4e7e-bfc8-4ef283ee4b19",

"name": "Jason Miller",

"gender": "male",

"dateOfBirth": "23/04/1990",

"email": "jason@mail.com",

"password": "666349420ec497c1dc890c45179d44fb13220239325172af02d1fb6635922956"

},

{

"id": "2b9130d4-47a7-4085-800e-0144f6a46059",

"name": "Tiffany Brookston",

"gender": "female",

"dateOfBirth": "09/06/1996",

"email": "tiffy@mail.com",

"password": "8a1ea5669b749354110dcba3fac5546c16e6d0f73a37f35a84f6b0d7b3c22fcc"

},

{

"id": "11817fb1-03a1-4b4a-8d27-854ac893cf41",

"name": "Catrin Stevenson",

"gender": "female",

"dateOfBirth": "17/08/2001",

"email": "catrin@mail.com",

"password": "18eb2d6c5373c94c6d5d707650d02c3c06f33fac557c9cfb8cb1ee625a649ff3"

},

{

"id": "6a89217b-7c28-4219-bd7f-af119c314159",

"name": "Greg Bronson",

"gender": "male",

"dateOfBirth": "08/04/1993",

"email": "greg@mail.com",

"password": "a6dcde7eceb689142f21a1e30b5fdb868ec4cd25d5537d67ac7e8c7816b0e862"

}

]

}

Before you start asking – yes, the passwords are hashed. 😉

After that, add some "records" under "members".

{

"workouts": [ ...

],

"members": [ ...

],

"records": [

{

"id": "ad75d475-ac57-44f4-a02a-8f6def58ff56",

"workout": "4a3d9aaa-608c-49a7-a004-66305ad4ab50",

"record": "160 reps"

},

{

"id": "0bff586f-2017-4526-9e52-fe3ea46d55ab",

"workout": "d8be2362-7b68-4ea4-a1f6-03f8bc4eede7",

"record": "7:23 minutes"

},

{

"id": "365cc0bb-ba8f-41d3-bf82-83d041d38b82",

"workout": "a24d2618-01d1-4682-9288-8de1343e53c7",

"record": "358 reps"

},

{

"id": "62251cfe-fdb6-4fa6-9a2d-c21be93ac78d",

"workout": "4a3d9aaa-608c-49a7-a004-66305ad4ab50",

"record": "145 reps"

}

],

}

To make sure you've got the same workouts like I do with the same id's, copy the workouts as well:

{

"workouts": [

{

"id": "61dbae02-c147-4e28-863c-db7bd402b2d6",

"name": "Tommy V",

"mode": "For Time",

"equipment": [

"barbell",

"rope"

],

"exercises": [

"21 thrusters",

"12 rope climbs, 15 ft",

"15 thrusters",

"9 rope climbs, 15 ft",

"9 thrusters",

"6 rope climbs, 15 ft"

],

"createdAt": "4/20/2022, 2:21:56 PM",

"updatedAt": "4/20/2022, 2:21:56 PM",

"trainerTips": [

"Split the 21 thrusters as needed",

"Try to do the 9 and 6 thrusters unbroken",

"RX Weights: 115lb/75lb"

]

},

{

"id": "4a3d9aaa-608c-49a7-a004-66305ad4ab50",

"name": "Dead Push-Ups",

"mode": "AMRAP 10",

"equipment": [

"barbell"

],

"exercises": [

"15 deadlifts",

"15 hand-release push-ups"

],

"createdAt": "1/25/2022, 1:15:44 PM",

"updatedAt": "3/10/2022, 8:21:56 AM",

"trainerTips": [

"Deadlifts are meant to be light and fast",

"Try to aim for unbroken sets",

"RX Weights: 135lb/95lb"

]

},

{

"id": "d8be2362-7b68-4ea4-a1f6-03f8bc4eede7",

"name": "Heavy DT",

"mode": "5 Rounds For Time",

"equipment": [

"barbell",

"rope"

],

"exercises": [

"12 deadlifts",

"9 hang power cleans",

"6 push jerks"

],

"createdAt": "11/20/2021, 5:39:07 PM",

"updatedAt": "4/22/2022, 5:49:18 PM",

"trainerTips": [

"Aim for unbroken push jerks",

"The first three rounds might feel terrible, but stick to it",

"RX Weights: 205lb/145lb"

]

},

{

"name": "Core Buster",

"mode": "AMRAP 20",

"equipment": [

"rack",

"barbell",

"abmat"

],

"exercises": [

"15 toes to bars",

"10 thrusters",

"30 abmat sit-ups"

],

"trainerTips": [

"Split your toes to bars in two sets maximum",

"Go unbroken on the thrusters",

"Take the abmat sit-ups as a chance to normalize your breath"

],

"id": "a24d2618-01d1-4682-9288-8de1343e53c7",

"createdAt": "4/22/2022, 5:50:17 PM",

"updatedAt": "4/22/2022, 5:50:17 PM"

}

],

"members": [ ...

],

"records": [ ...

]

}

Okay, let's take a few minutes to think about our implementation.

We've got a resource called "workouts" on the one side and another called "records" on the other side.

To move on in our architecture it would be advisable to create another controller, another service, and another collection of database methods that are responsible for records.

Chances are high that have we to implement CRUD endpoints for the records as well, because records should be added, updated or deleted in the future as well. But this won't be the primary task for now.

We'll also need a record router to catch the specific requests for the records, but we don't need it right now. This could be a great chance for you to implement the CRUD operations for the records with their own routes and train a bit.

# Create records controller

touch src/controllers/recordController.js

# Create records service

touch src/services/recordService.js

# Create records database methods

touch src/database/Record.js

That was easy. Let's move on and start backwards with implementing our database methods.

// In src/database/Record.js

const DB = require("./db.json");

const getRecordForWorkout = (workoutId) => {

try {

const record = DB.records.filter((record) => record.workout === workoutId);

if (!record) {

throw {

status: 400,

message: `Can't find workout with the id '${workoutId}'`,

};

}

return record;

} catch (error) {

throw { status: error?.status || 500, message: error?.message || error };

}

};

module.exports = { getRecordForWorkout };

Pretty straightforward, right? We filter all the records that are related to the workout id out of the query parameter.

The next one is our record service:

// In src/services/recordService.js

const Record = require("../database/Record");

const getRecordForWorkout = (workoutId) => {

try {

const record = Record.getRecordForWorkout(workoutId);

return record;

} catch (error) {

throw error;

}

};

module.exports = { getRecordForWorkout };

Again, nothing new here.

Now we're able to create a new route in our workout router and direct the request to our record service.

// In src/v1/routes/workoutRoutes.js

const express = require("express");

const workoutController = require("../../controllers/workoutController");

// *** ADD ***

const recordController = require("../../controllers/recordController");

const router = express.Router();

router.get("/", workoutController.getAllWorkouts);

router.get("/:workoutId", workoutController.getOneWorkout);

// *** ADD ***

router.get("/:workoutId/records", recordController.getRecordForWorkout);

router.post("/", workoutController.createNewWorkout);

router.patch("/:workoutId", workoutController.updateOneWorkout);

router.delete("/:workoutId", workoutController.deleteOneWorkout);

module.exports = router;

Great! Let's test things out in our browser.

First, we fetch all workouts to get a workout id.

Let's see if we can fetch all records for that:

As you can see, logical nesting makes sense when you have resources that can be tied together. Theoretically you can nest it how deep you want, but the rule of thumb here is to go three levels deep at a maximum.

If you want to nest deeper than that, you could do a little tweak inside your database records. I'll show you a little example.

Imagine the frontend also needs an endpoint to get information about which member exactly holds the current record and wants to receive metadata about them.

Of course we could implement the following URI:

GET /api/v1/workouts/:workoutId/records/members/:memberId

The endpoint now becomes less manageable the more nesting we add to it. Therefore it's a good practice to store the URI to receive information about a member directly into the record.

Consider the following inside the database:

{

"workouts": [ ...

],

"members": [ ...

],

"records": [ ... {

"id": "ad75d475-ac57-44f4-a02a-8f6def58ff56",

"workout": "4a3d9aaa-608c-49a7-a004-66305ad4ab50",

"record": "160 reps",

"memberId": "11817fb1-03a1-4b4a-8d27-854ac893cf41",

"member": "/members/:memberId"

},

]

}

As you can see, we've added the two properties "memberId" and "member" to our records inside the database. This has the huge advantage that we don't have to nest deeper our existing endpoint.

The frontend just needs to call GET /api/v1/workouts/:workoutId/records and receives automatically all records that are connected with this workout.

On top of that it gets the member id and the endpoint to fetch information about that member. So, we avoided the deeper nesting of our endpoint.

Of course, this only works if we can handle requests to "/members/:memberId" 😁 This sounds like a great training opportunity for you to implement this situation!

Integrate filtering, sorting & pagination

Right now we're able to do quite a few operations with our API. That's great progress, but there's more.

During the last sections we focused on improving our developer experience and how our API can be interacted with. But the overall performance of our API is another key factor we should work on.

That's why integrating filtering, sorting, and pagination is also an essential factor on my list.

Imagine we've got 2,000 workouts, 450 records, and 500 members stored in our DB. When calling our endpoint to get all workouts we don't want to send all 2,000 workouts at once. This will be a very slow response of course, or it'll bring our systems down (maybe with 200,000 😁).

That's the reason why filtering and pagination are important. Filtering, as the name already says, is useful because it allows us to get specific data out of our whole collection. For example all workouts that have the mode "For Time".

Pagination is another mechanism to split our whole collection of workouts into multiple "pages" where each page only consists of twenty workouts, for example. This technique helps us to make sure that we don't send more than twenty workouts at the same time with our response to the client.

Sorting can be a complex task. So it's more effective to do it in our API and to send the sorted data to the client.

Let's start with integrating some filtering mechanism into our API. We will upgrade our endpoint that sends all workouts by accepting filter parameters. Normally in a GET request we add the filter criteria as a query parameter.

Our new URI will look like this, when we'd like to get only the workouts that are in the mode of "AMRAP" (As Many Rounds As Possible): /api/v1/workouts?mode=amrap.

To make this more fun we need to add some more workouts. Paste these workouts into your "workouts" collection inside db.json:

{

"name": "Jumping (Not) Made Easy",

"mode": "AMRAP 12",

"equipment": [

"jump rope"

],

"exercises": [

"10 burpees",

"25 double-unders"

],

"trainerTips": [

"Scale to do 50 single-unders, if double-unders are too difficult"

],

"id": "8f8318f8-b869-4e9d-bb78-88010193563a",

"createdAt": "4/25/2022, 2:45:28 PM",

"updatedAt": "4/25/2022, 2:45:28 PM"

},

{

"name": "Burpee Meters",

"mode": "3 Rounds For Time",

"equipment": [

"Row Erg"

],

"exercises": [

"Row 500 meters",

"21 burpees",

"Run 400 meters",

"Rest 3 minutes"

],

"trainerTips": [

"Go hard",

"Note your time after the first run",

"Try to hold your pace"

],

"id": "0a5948af-5185-4266-8c4b-818889657e9d",

"createdAt": "4/25/2022, 2:48:53 PM",

"updatedAt": "4/25/2022, 2:48:53 PM"

},

{

"name": "Dumbbell Rower",

"mode": "AMRAP 15",

"equipment": [

"Dumbbell"

],

"exercises": [

"15 dumbbell rows, left arm",

"15 dumbbell rows, right arm",

"50-ft handstand walk"

],

"trainerTips": [

"RX weights for women: 35-lb",

"RX weights for men: 50-lb"

],

"id": "3dc53bc8-27b8-4773-b85d-89f0a354d437",

"createdAt": "4/25/2022, 2:56:03 PM",

"updatedAt": "4/25/2022, 2:56:03 PM"

}

After that we have to accept and handle query parameters. Our workout controller will be the right place to start:

// In src/controllers/workoutController.js

...

const getAllWorkouts = (req, res) => {

// *** ADD ***

const { mode } = req.query;

try {

// *** ADD ***

const allWorkouts = workoutService.getAllWorkouts({ mode });

res.send({ status: "OK", data: allWorkouts });

} catch (error) {

res

.status(error?.status || 500)

.send({ status: "FAILED", data: { error: error?.message || error } });

}

};

...

We're extracting "mode" from the req.query object and defining a parameter of workoutService.getAllWorkouts. This will be an object that consists of our filter parameters.

I'm using the shorthand syntax here, to create a new key called "mode" inside the object with the value of whatever is in "req.query.mode". This could be either a truthy value or undefined if there isn't a query parameter called "mode". We can extend this object the more filter parameters we'd like to accept.

In our workout service, pass it to your database method:

// In src/services/workoutService.js

...

const getAllWorkouts = (filterParams) => {

try {

// *** ADD ***

const allWorkouts = Workout.getAllWorkouts(filterParams);

return allWorkouts;

} catch (error) {

throw error;

}

};

...

Now we can use it in our database method and apply the filtering:

// In src/database/Workout.js

...

const getAllWorkouts = (filterParams) => {

try {

let workouts = DB.workouts;

if (filterParams.mode) {

return DB.workouts.filter((workout) =>

workout.mode.toLowerCase().includes(filterParams.mode)

);

}

// Other if-statements will go here for different parameters

return workouts;

} catch (error) {

throw { status: 500, message: error };

}

};

...

Pretty straightforward, right? All we do here is check if we actually have a truthy value for the key "mode" inside our "filterParams". If this is true, we filter all those workouts that have got the same "mode". If this is not true, then there is no query parameter called "mode" and we return all workouts because we don't need to filter.

We defined "workouts" here as a "let" variable because when adding more if-statements for different filters we can overwrite "workouts" and chain the filters.

Inside your browser you can visit localhost:3000/api/v1/workouts?mode=amrap and you'll receive all "AMRAP" workouts that are stored:

If you leave the query parameter out, you should get all workouts like before. You can try it further with adding "for%20time" as the value for the "mode" parameter (remember --> "%20" means "whitespace") and you should receive all workouts that have the mode "For Time" if there are any stored.

When typing in a value that is not stored, that you should receive an empty array.

The parameters for sorting and pagination follow the same philosophy. Let's look at a few features we could possibly implement:

- Receive all workouts that require a barbell: /api/v1/workouts?equipment=barbell

- Get only 5 workouts: /api/v1/workouts?length=5

- When using pagination, receive the second page: /api/v1/workouts?page=2

- Sort the workouts in the response in descending order by their creation date: /api/v1/workouts?sort=-createdAt

- You can also combine the parameters, to get the last 10 updated workouts for example: /api/v1/workouts?sort=-updatedAt&length=10

Use data caching for performance improvements

Using a data cache is also a great practice to improve the overall experience and performance of our API.

It makes a lot of sense to use a cache to serve data from, when the data is an often requested resource or/and querying that data from the database is a heavy lift and may take multiple seconds.

You can store this type of data inside your cache and serve it from there instead of going to the database every time to query the data.

One important thing you have to keep in mind when serving data from a cache is that this data can become outdated. So you have to make sure that the data inside the cache is always up to date.

There are many different solutions out there. One appropriate example is to use redis or the express middleware apicache.

I'd like to go with apicache, but if you want to use Redis, I can highly recommend that you check out their great docs.

Let's think a second about a scenario in our API where a cache would make sense. I think requesting to receive all workouts would effectively be served from our cache.

First, let's install our middleware:

npm i apicache

Now, we have to import it into our workout router and configure it.

// In src/v1/routes/workoutRoutes.js

const express = require("express");

// *** ADD ***

const apicache = require("apicache");

const workoutController = require("../../controllers/workoutController");

const recordController = require("../../controllers/recordController");

const router = express.Router();

// *** ADD ***

const cache = apicache.middleware;

// *** ADD ***

router.get("/", cache("2 minutes"), workoutController.getAllWorkouts);

router.get("/:workoutId", workoutController.getOneWorkout);

router.get("/:workoutId/records", recordController.getRecordForWorkout);

router.post("/", workoutController.createNewWorkout);

router.patch("/:workoutId", workoutController.updateOneWorkout);

router.delete("/:workoutId", workoutController.deleteOneWorkout);

module.exports = router;

Getting started is pretty straightforward, right? We can define a new cache by calling apicache.middleware and use it as a middleware inside our get route. You just have to put it as a parameter between the actual path and our workout controller.

Inside there you can define how long your data should be cached. For the sake of this tutorial I've chosen two minutes. The time depends on how fast or how often your data inside your cache changes.

Let's test things out!

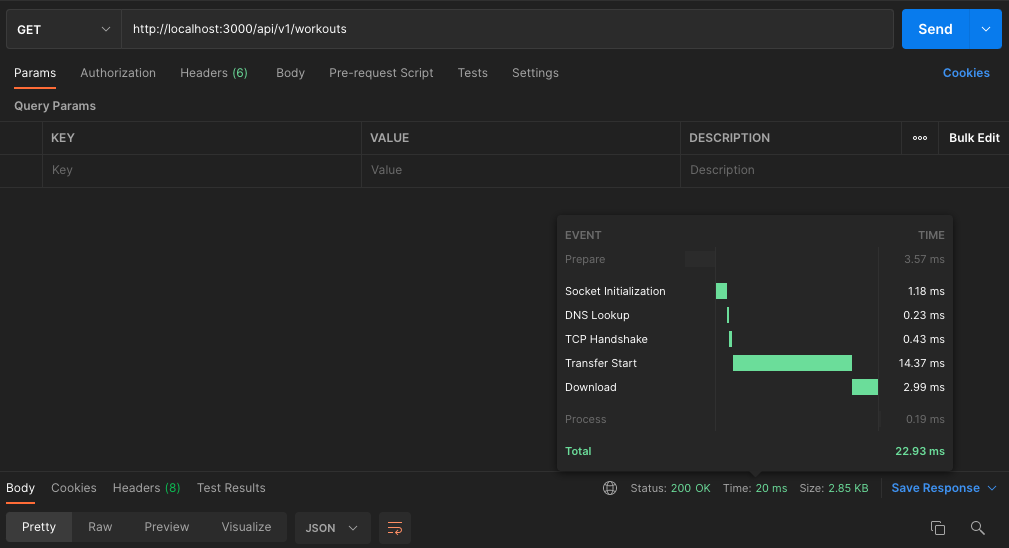

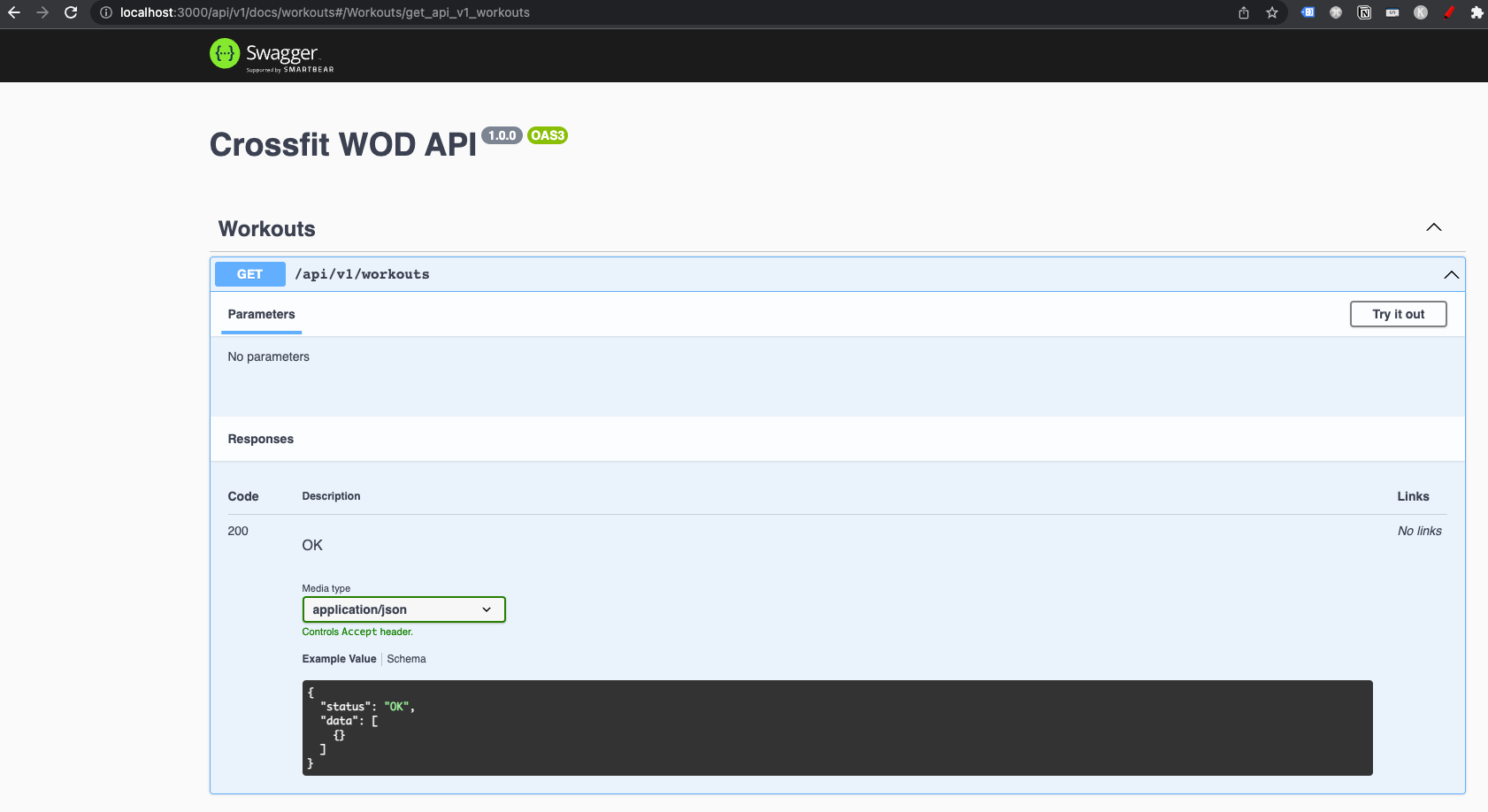

Inside Postman or another HTTP client of your choice, define a new request that gets all workouts. I've done it inside the browser until now, but I'd like to visualize the response times better for you. That's the reason why I'm requesting the resource via Postman right now.

Let's call our request for the first time:

As you can see it took our API 22.93 ms to respond. Once our cache is empty again (after two minutes) it has to be filled again. This happens with our first request.

So in the case above, the data was NOT served from our cache. It took the "regular" way from the database and filled our cache.

Now, with our second request we receive a shorter response time, because it was directly served from the cache:

We were able to serve three times faster than in our previous request! All thanks to our cache.

In our example we've cached just one route, but you can also cache all routes by implementing it like this:

// In src/index.js

const express = require("express");

const bodyParser = require("body-parser");

// *** ADD ***

const apicache = require("apicache");

const v1WorkoutRouter = require("./v1/routes/workoutRoutes");

const app = express();

// *** ADD ***

const cache = apicache.middleware;

const PORT = process.env.PORT || 3000;

app.use(bodyParser.json());

// *** ADD ***

app.use(cache("2 minutes"));

app.use("/api/v1/workouts", v1WorkoutRouter);

app.listen(PORT, () => {

console.log(`API is listening on port ${PORT}`);

});

There's one important thing I'd like to note here when it comes to caching. While it seems to solve a lot of problems for you, it also can bring some problems into your application.

A few things you have to be aware of when using a cache:

- you always have to make sure that the data inside the cache is up to date because you don't want to serve outdated data

- while the first request is being processed and the cache is about to be filled and more requests are coming in, you have to decide if you delay those other requests and serve the data from the cache or if they also receive data straight from the database like the first request

- it's another component inside your infrastructure if you're choosing a distributed cache like Redis (so you have to ask yourself if it really makes sense to use it)

Here's how to do it usually:

I like to start as simple and as clean as possible with everything I build. The same goes for API's.

When I start building an API and there are no particular reasons to use a cache straight away, I leave it out and see what happens over time. When reasons arise to use a cache, I can implement it then.

Good security practices

Wow! This has been quite a great journey so far. We've touched on many important points and extended our API accordingly.

We've spoken about best practices to increase the usability and performance of our API. Security is also a key factor for API's. You can build the best API, but when it is a vulnerable piece of software running on a server it becomes useless and dangerous.