By Yan Cui

I recently left Space Ape Games after a wonderful year. I learnt a lot, and worked on some challenging technical problems.

Here are seven lessons that I learned from one of the most well-run companies I have encountered in my 13 year career.

Define what culture you want, and organize yourself to optimize towards achieving that culture

Lots of companies talk about how great their culture is, but few talk about what their culture actually is. Worse yet, I suspect most end up with a culture they don’t want, because the culture grew organically and without guidance.

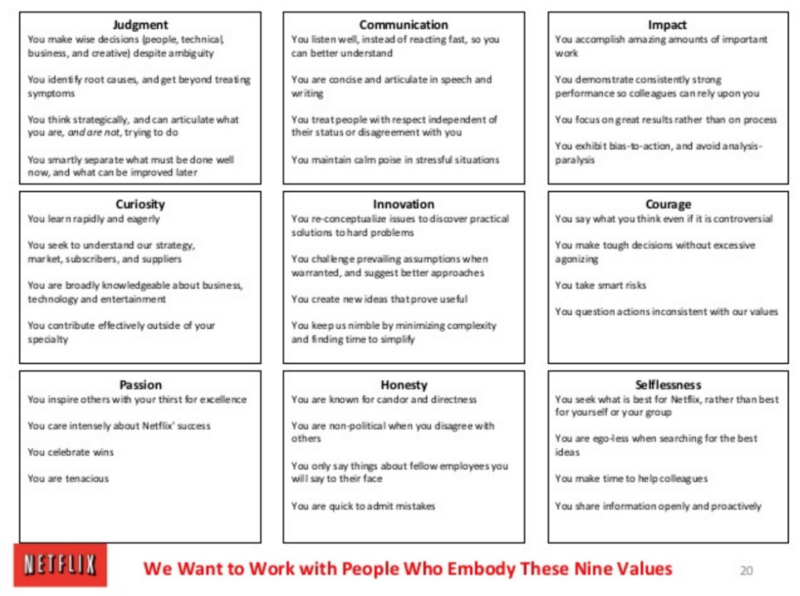

To this day, the Netflix culture deck from 2009 is still the one of the best things you can read about culture.

Real company values are the behaviors and skills that we particularly value in fellow employees.

— Reed Hastings

Be clear about the culture you want to build from the start. These are the characteristics and skills that we value in each other at Space Ape:

Passionate: you have a passion for games, and you want to build games that are fun and engaging.

Creative: you are not afraid to stray off the beaten path and try something new. You accept the risks that come with creativity. You won’t let failures stop you from succeeding.

Judgement: you make smart bets. You balance the risks of creativity with methodical analysis of the potential rewards to make smart bets.

Dependable: you are dependable and trustworthy. We believe in small, autonomous teams. For this to work, we need to be able to depend on every individual in the team.

Focus: when required, you can put aside personal projects and focus on delivering the best game possible.

Mastery: you are a master of your craft. You want to become the best version of yourself and are always looking for ways to improve.

Collaborative: you work well with others. You are willing to make sacrifices and compromises for the greater good of the company. Game making is an inherently creative and collaborative process. We need people that can thrive in a collaborative environment.

Inclusive: you welcome others for who they are. You treat others equally and fairly, the same way that you expect to be treated.

Reiterate this vision regularly. We find that if it is not reiterated at least once every couple of months, then it starts to slip through the collective consciousness.

Make sure new employees are imbued with your vision. And remind employees of their duty to maintain your culture.

Culture lives and dies by the people you hire and fire

This shared understanding of culture needs to filter through to every hiring decision.

“Culture fit” is often used to enforce existing biases, especially when said culture is never defined up front to begin with. Fortunately, this has never been the case in any of the hiring committees I have sat on. Whenever “culture fit” is raised as a concern, you must give clear examples from your interaction with the interviewee.

At the same time, you shouldn’t hire someone who might be detrimental to your culture — not even when you are desperate for another pair of hands on deck!

The cost of a bad hire to your culture is too great.

The founders also act as the vanguards for your culture. They watch from afar, but they’re never afraid to step in when they see the danger signs. If a long time employee starts to show signs of self-entitlement, then expect a gentle reminder about the company’s commitment to inclusion and fairness.

Even when you have built a great culture, you can’t afford to take it for granted. It’s the duty of everyone involved to keep that culture strong.

People are your most important product

This is true for most companies, which is why it should be a no-brainer to invest in the people and help them grow.

Offer training budgets to everyone, and provide managers with management coaches. The results will be well worth it.

Founders need to communicate the vision of the company openly, clearly, and frequently

Avoid impressive-sounding but vague mission statements. Vague goals that do not define clear, actionable targets are hard to follow and apply. Collaboration suffers when people do not have a shared understanding of the company vision.

Our founders reiterate the company mission at every quarterly company meeting. The repetition has been important in reinforcing the shared understanding of the goal. I recently also saw Ryan Caldbeck, the CEO of CircleUp, say the same thing on Twitter.

Our mission statement is “to build a top grossing mobile game by owning a genre.” Simple, unglamorous, but easy to understand.

Be honest about conflict of interest

Managers usually have the best intentions when they set out personal objectives for their charges. Everyone gets a set of objectives that align with the company’s goal. Where is the conflict of interest?

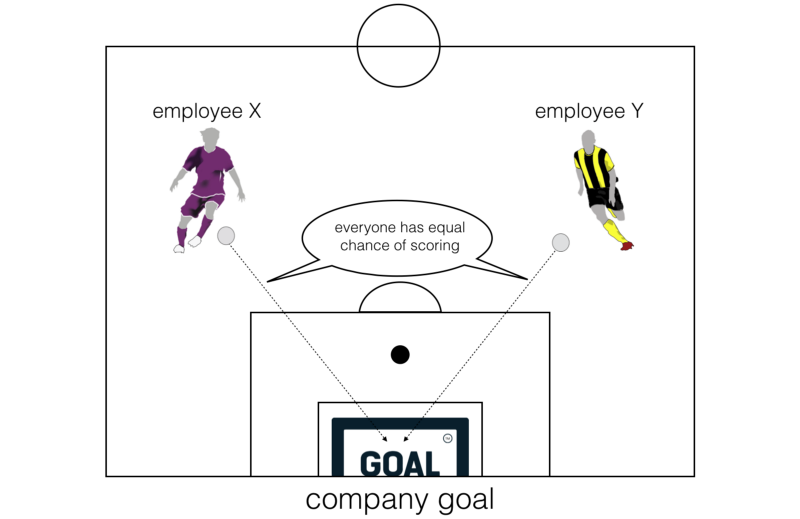

What you might think when you set out personal objectives.

What you might think when you set out personal objectives.

Things seldom work out as you expect, though. What usually happens is that some projects will go more smoothly than others. At the same time, some projects deliver more value to the company than others.

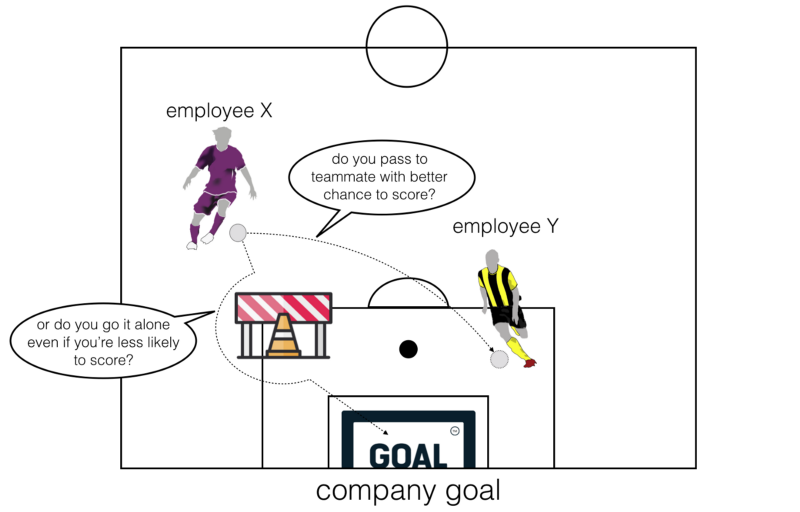

Nod if this scenario sounds familiar.

You’re working on project X, and your end of year pay raise, bonus, and promotion hopes are all riding on the success of project X.

A colleague is working on project Y, and he needs you to work on something to unblock his project. Project Y is more valuable to the company, but helping this colleague means losing progress on project X.

What do you do?

Do you do the right thing by the company and help this colleague? In the process you might lose the pay raise, bonus, and promotion that you have worked so hard for.

Or do you put his request in the backlog and focus on project X?

Hello, conflict of interest.

What actually happens when employees need to collaborate with one another, and often have to sacrifice their self-interest for the greater good of the company.

What actually happens when employees need to collaborate with one another, and often have to sacrifice their self-interest for the greater good of the company.

If you think this only happens in poorly-run companies, then you’re wrong. Even Google is not immune to this conflict of interest, as is evident in Michael Lynch’s article on why he quit Google.

Teamwork requires willing sacrifice.

In football, a “team player” carries the connotation of being willing to sacrifice themselves for the team. Be it risking injury in a 50–50 challenge, or passing to a teammate who’s more likely to score.

How do you translate this to the work place? How do you encourage people to make willing sacrifices for the good of the company?

You have to start by being honest about this conflict of interest.

Your employees are not saints, they are flesh and blood with real world problems. What if they need the pay raise to start a family? And what’s wrong with wanting career progression?

Employees have every right to act in their best interest. It is your job as employer to create an environment where employees are not penalized for making self-sacrifice.

You can do this in several ways.

The biggest, most effective way is to separate personal objectives and 360 reviews from performance and salary reviews.

Personal objectives are for your personal development only. Your manager can help you decide what areas to improve on, but the final decision is yours. You’re encouraged, but not required, to set personal objectives.

360 reviews are also for you and you alone. You choose from whom you want feedback, and how to proceed with the feedback you receive.

The feedback is anonymous, and only the manager of the reviewer knows who delivered that feedback. This is mainly to mitigate any unnecessary tension from ill-considered feedback.

Your manager and the founders are also there to help you process the feedback if you need their help.

Performance and salary reviews are based on what you actually contributed, not some arbitrary targets that were set months ago.

For us, this unusual way of working started with a frank discussion about this conflict of interest. It has been iterated upon over time and will continue to evolve. It’s been such a fresh breath of air for me to work for a company that not only recognizes the problem but actively seeks to tackle it.

Marry creativity with ownership

Cultivate creativity from the whole company using game jams and hackathons. But remember that creativity needs to be guided, and hypotheses need to be tested.

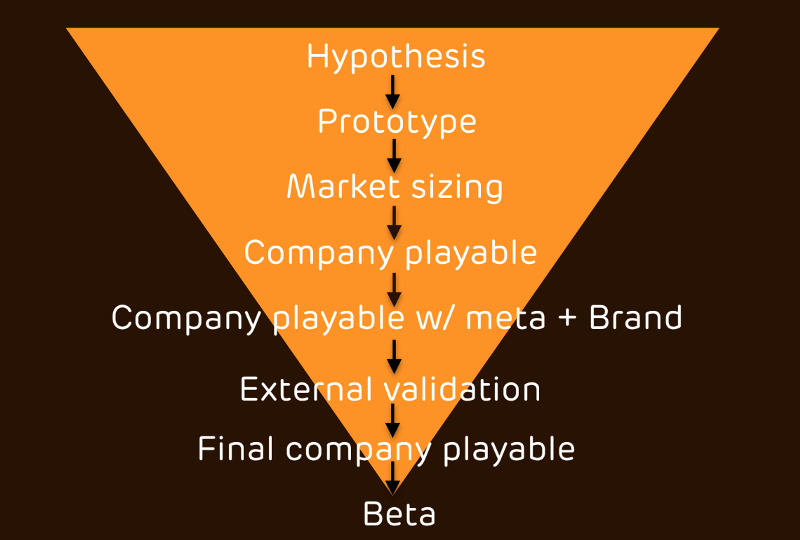

We use a creative funnel to guide ideas from hypothesis to production.

The game jams generate ideas to feed the top of the funnel. Everyone can come up with ideas for new games. You have the ownership and responsibility to polish your idea and pitch it to the rest of the company.

Teams form organically around ideas that they’re excited about and believe can be top-grossing. This is NOT a top-down decision.

The founders are there to offer guidance and help with personnel movement. Whilst your idea might be great, the founders can guide you on shaping the idea to fit your mission.

Is it economically feasible to build?

What is the market competition like? Is the genre saturated with high quality offerings already? Does this genre have top grossing potential?

Do we have the technical expertise to build it? If not, how difficult is it to hire someone with that expertise?

The teams that form around an idea focus on prototyping and iterating on the idea. The idea becomes a playable game, and the rest of the company then plays and provides feedback.

The team owns the idea, and is trusted with making the decisions to keep going or kill it if they no longer believe in it. Again, this is NOT a top-down decision — the decision is made within the team.

Which brings us to the next point.

Recognize that creativity requires mistakes

Creativity needs failures to succeed.

Being creative and experimenting with new ideas means taking on risks. If you don’t risk, you will not win big — at least not without the marketing budget and brand that goes with established franchises.

To let teams take on risk, and to trust them to make the right decision on the company’s behalf and kill a prototype, is hard.

For this to happen, you need an environment where employees are not penalized for making sacrifices.

We do this by creating a safety net for jobs.

Your job is not tied to the prototype. If a team decides to kill its idea, then the team members move into other game teams, or they’ll stay together and prototype another game idea.

To prove this approach works beyond our scale, consider Supercell and Clash Royale. The team behind Clash Royale was working on another idea before they came up with that one. The idea tested well in beta, it had good retention and monetization stats. But it was not great, certainly not on par with Clash of Clans.

The team made the decision to kill the idea because they believed they could do better. So they took the learnings from the previous game, iterated on the ideas further, and they created Clash Royale.

Recognize that people and their talents are your greatest assets. Hire and keep great people rather than hiring for and keeping certain roles.

Conclusions

So there you have it. Seven things that I learned from my time at Space Ape Games.

What stood out most for me is that a company needs to have a clear identity — it needs to know who it wants to be, and it needs to organize itself to become that company.

And while I love the ethos on small autonomous teams, and the flat hierarchy structure, it also has a downside: at this stage of my career, I am accustomed to having a wide range of responsibilities, and I crave it.

As time went by, I felt that itch for more responsibility creeping back. When my old friend Bruno Tavares pitched me the idea of joining DAZN to work on all the great things they’re doing, it was hard to say no.

With a heavy heart, this is my farewell letter to Space Ape Games and the great people within. You guys are awesome! And I hope the lessons I’ve learned there help others as well.