By Haseeb Qureshi

(Kinda.)

Hack the planet, everybody.

Hack the planet, everybody.

I have no self-control.

Luckily, I know this about myself. This allows me to consciously engineer my life so that despite having the emotional maturity of a heroin-addicted lab rat, I’m occasionally able to get things done.

I waste a lot of time on Reddit. If I want to procrastinate on something, I’ll often open a new tab and dive down a Reddit-hole. But sometimes you need to turn on the blinders and dial down distractions. 2015 was one of these times — I was singularly focused on improving as a programmer, and Redditing was becoming a liability.

I needed an abstinence plan.

So it occurred to me: how about I lock myself out of my account?

Here’s what I did:

I set a random password on my account. Then I asked a friend to e-mail me this password on a certain date. With that, I’d have a foolproof way to lock myself out of Reddit. (Also changed the e-mail for password recovery to cover all the bases.)

This should have worked.

Unfortunately it turns out, friends are very susceptible to social engineering. The technical terminology for this is that they are “nice to you” and will give you back your password if you “beg them.”

After a few rounds of this failure mode, I needed a more robust solution. A little Google searching, and I came across this:

Looks legit.

Looks legit.

Perfect — an automated, friend-less solution! (I’d alienated most of them by now, so that was a big selling point.)

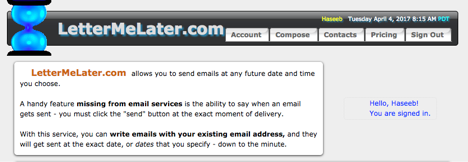

A bit sketchy looking, but hey, any port in a storm.

For a while I set this up this routine — during the week I’d e-mail myself my password, on the weekends I’d receive the password, load up on internet junk food, and then lock myself out again once the week began. It worked quite well from what I remember.

Eventually I got so busy with programming stuff, I completely forgot about it.

Cut to two years later.

I’m now gainfully employed at Airbnb. And Airbnb, it so happens, has a large test suite. This means waiting, and waiting of course means internet rabbit holes.

I decide to scrounge up my old account and find my Reddit password.

Oh no. That’s not good.

I didn’t remember doing this, but I must have gotten so fed up with myself that I locked myself out until 2018. I also set it to “hide,” so I couldn’t view the contents of the e-mail until it’s sent.

What do I do? Do I just have to create a new Reddit account and start from scratch? But that’s so much work.

I could write in to LetterMeLater and explain that I didn’t mean to do this. But they would probably take a while to get back to me. We’ve already established I’m wildly impatient. Plus this site doesn’t look like it has a support team. Not to mention it would be an embarrassing e-mail exchange. I started brainstorming elaborate explanations involving dead relatives about why I needed access to the e-mail…

All of my options were messy. I was walking home that night from the office pondering my predicament, when suddenly it hit me.

The search bar.

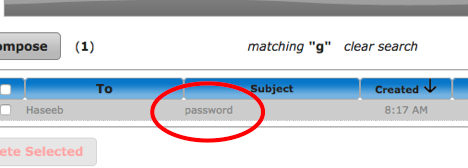

I pulled up the app on my mobile phone and tried it:

Hmm.

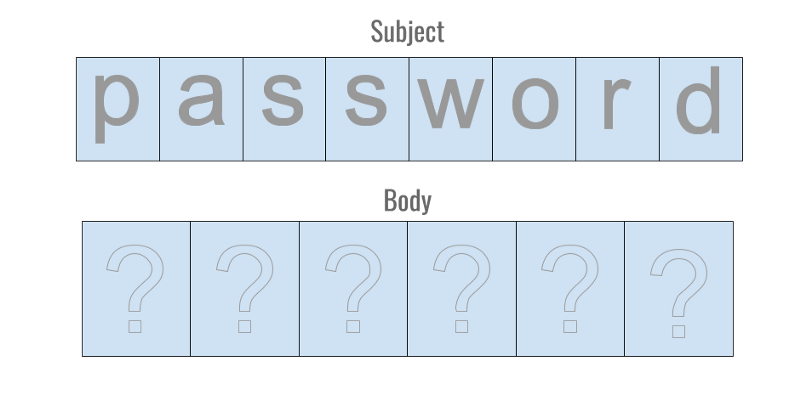

Okay. So it’s indexing the subject for sure. What about the body?

I try a few letters, and voila. It’s definitely got the body indexed. Remember: the body consisted entirely of my password.

Essentially, I’ve been given an interface to perform substring queries. By entering in a string into the search bar, the search results will confirm whether my password contains this substring.

We’re in business.

I hurry into my apartment, drop my bag, and pull out my laptop.

Algorithms problem: you are given a function substring?(str), which returns true or false depending on whether a password contains any given substring. Given this function, write an algorithm that can deduce the hidden password.

The Algorithm

So let’s think about this. A few things I know about my password: I know it was a long string with some random characters, probably something along the lines of asgoihej2409g. I probably didn’t include any upper-case characters (and Reddit doesn’t enforce that as a password constraint) so let’s assume for now that I didn’t — in case I did, we can just expand the search space later if the initial algorithm fails.

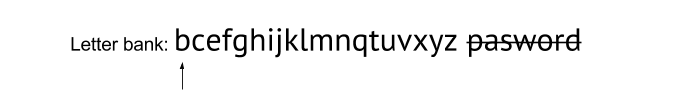

We also have a subject line as part of the string we’re querying. And we know the subject is “password”.

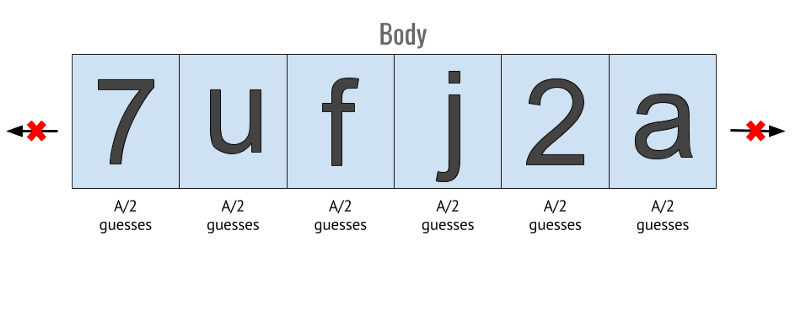

Let’s pretend the body is 6 characters long. So we’ve got six slots of characters, some of which may appear in the subject line, some of which certainly don’t. So if we take all of the characters that aren’t in the subject and try searching for each of them, we know for sure we’ll hit a unique letter that’s in the password. Think like a game of Wheel of Fortune.

We keep trying letters one by one until we hit a match for something that’s not in our subject line. Say we hit it.

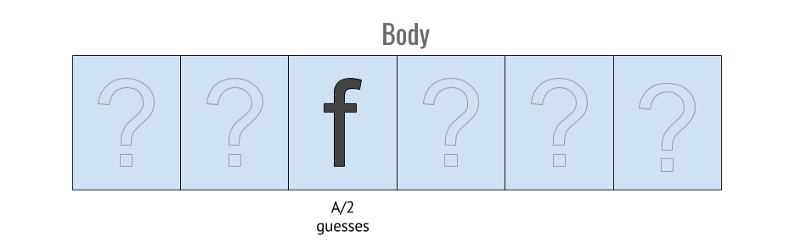

Once I’ve found my first letter, I don’t actually know where in this string I am. But I know I can start building out a bigger substring by appending different characters to the end of this until I hit another substring match.

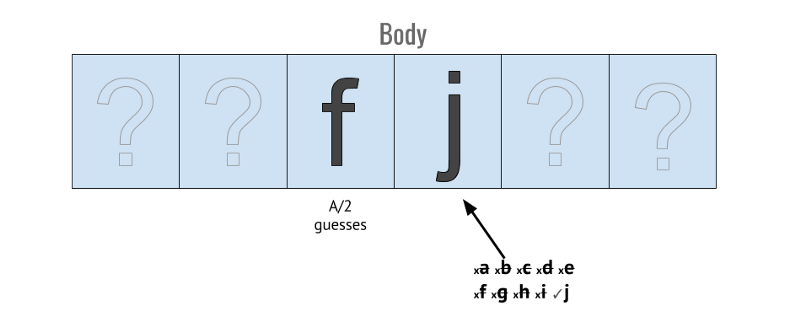

We’ll potentially have to iterate through every character in our alphabet to find it. Any of those characters could be correct, so on average it’ll hit somewhere around the middle, so given an alphabet of size A, it should average out to A/2 guesses per letter (let’s assume the subject is small and there are no repeating patterns of 2+ characters).

I’ll keep building this substring until it eventually hits the end and no characters can extend it further.

But that’s not enough — most likely, there will be a prefix to the string that I missed, because I started in a random place. Easy enough: all I have to do is now repeat the process, except going backwards.

Once the process terminates, I should be able to reconstruct the password. In total, I’ll need to figure outL characters(where L is the length), and need to expend on average A/2 guesses per character (where A is the alphabet size), so total guesses = A/2 * L.

To be precise, I also have to add another 2A to the number of guesses for ascertaining that the string has terminated on each end. So the total is A/2 * L + 2A, which we can factor as A(L/2 + 2).

Let’s assume we have 20 characters in our password, and an alphabet consisting of a-z (26) and 0–9 (10), so a total alphabet size of 36. So we’re looking at an average of 36 * (20/2 + 2) = 36 * 12 = 432 iterations.

Damn.

This is actually doable.

The Implementation

First things first: I need to write a client that can programmatically query the search box. This will serve as my substring oracle. Obviously this site has no API, so I’ll need to scrape the website directly.

Looks like the URL format for searching is just a simple query string, www.lettermelater.com/account.php?**qe=#{query_here}**. That’s easy enough.

Let’s start writing this script. I’m going to use the Faraday gem for making web requests, since it has a simple interface that I know well.

I’ll start by making an API class.

Of course, we don’t expect this to work yet, as our script won’t be authenticated into any account. As we can see, the response returns a 302 redirect with an error message provided in the cookie.

[10] pry(main)> Api.get(“foo”)

=> #<Faraday::Response:0x007fc01a5716d8

...

{“date”=>”Tue, 04 Apr 2017 15:35:07 GMT”,

“server”=>”Apache”,

“x-powered-by”=>”PHP/5.2.17",

“set-cookie”=>”msg_error=You+must+be+signed+in+to+see+this+page.”,

“location”=>”.?pg=account.php”,

“content-length”=>”0",

“connection”=>”close”,

“content-type”=>”text/html; charset=utf-8"},

status=302>

So how do we sign in? We need to send in our cookies in the header, of course. Using Chrome inspector we can trivially grab them.

(Not going to show my real cookie here, obviously. Interestingly, looks like it’s storing user_id client-side which is always a great sign.)

Through process of elimination, I realize that it needs both code and user_id to authenticate me… sigh.

So I add these to the script. (This is a fake cookie, just for illustration.)

[29] pry(main)> Api.get(“foo”)=> “\n<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC \”-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN\” \”http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/strict.dtd\">\n<html>\n<head>\n\t<meta http-equiv=\”content-type\” content=\”text/html; charset=UTF-8\” />\n\t<meta name=\”Description\” content=\”LetterMeLater.com allows you to send emails to anyone, with the ability to have them sent at any future date and time you choose.\” />\n\t<meta name=\”keywords\” content=\”schedule email, recurring, repeating, delayed, text messaging, delivery, later, future, reminder, date, time, capsule\” />\n\t<title>LetterMeLater.com — Account Information</title>…

[30] pry(main)> _.include?(“Haseeb”)=> true

It’s got my name in there, so we’re definitely logged in!

We’ve got the scraping down, now we just have to parse the result. Luckily, this pretty easy — we know it’s a hit if the e-mail result shows up on the page, so we just need to look for any string that’s unique when the result is present. The string “password” appears nowhere else, so that will do just nicely.

That’s all we need for our API class. We can now do substring queries entirely in Ruby.

[31] pry(main)> Api.include?('password')

=> true

[32] pry(main)> Api.include?('f')

=> false

[33] pry(main)> Api.include?('g')

=> true

Now that we know that works, let’s stub out the API while we develop our algorithm. Making HTTP requests is going to be really slow and we might trigger some rate-limiting as we’re experimenting. If we assume our API is correct, once we get the rest of the algorithm working, everything should just work once we swap the real API back in.

So here’s the stubbed API, with a random secret string:

We’ll inject the stubbed API into the class while we’re testing. Then for the final run, we’ll use the real API to query for the real password.

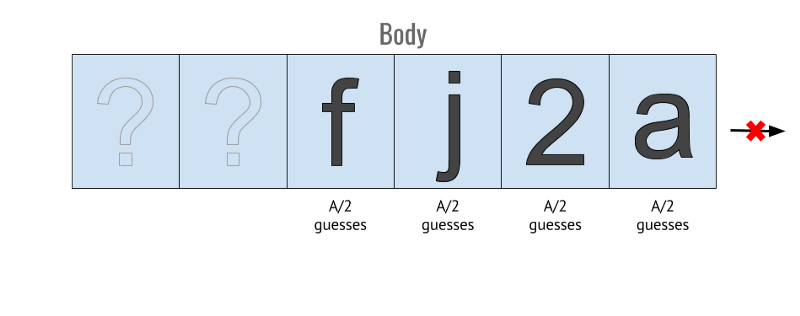

So let’s get started with this class. From a high level, recalling my algorithm diagram, it goes in three steps:

- First, find the first letter that’s not in the subject but exists in the password. This is our starting off point.

- Build those letters forward until we fall off the end of the string.

- Build that substring backwards until we hit the beginning of the string.

Then we’re done!

Let’s start with initialization. We’ll inject the API, and other than that we just need to initialize the current password chunk to be an empty string.

Now let’s write three methods, following the steps we outlined.

Perfect. Now the rest of the implementation can take place in private methods.

For finding the first letter, we need to iterate over each character in the alphabet that’s not contained in the subject. To construct this alphabet, we’re going to use a-z and 0–9. Ruby allows us to do this pretty easily with ranges:

ALPHABET = ((‘a’..’z’).to_a + (‘0’..’9').to_a).shuffle

I prefer to shuffle this to remove any bias in the password’s letter distribution. This will make our algorithm query A/2 times on average per character, even if the password is non-randomly distributed.

We also want to set the subject as a constant:

SUBJECT = ‘password’

That’s all the setup we need. Now time to write find_starting_letter. This needs to iterate through each candidate letter (in the alphabet but not in the subject) until it finds a match.

In testing, looks like this works perfectly:

PasswordCracker.new(ApiStub).send(:find_starting_letter!) # => 'f'

Now for the heavy lifting.

I’m going to do this recursively, because it makes the structure very elegant.

The code is surprisingly straightforward. Let’s see if it works with our stub API.

[63] pry(main)> PasswordCracker.new(ApiStub).crack!

f

fj

fjp

fjpe

fjpef

fjpefo

fjpefoj

fjpefoj4

fjpefoj49

fjpefoj490

fjpefoj490r

fjpefoj490rj

fjpefoj490rjg

fjpefoj490rjgs

fjpefoj490rjgsd

=> “fjpefoj490rjgsd”

Awesome. We’ve got a suffix, now just to build backward and complete the string. This should look very similar.

In fact, there’s only two lines of difference here: how we construct the guess, and the name of the recursive call. There’s an obvious refactoring here, so let’s do it.

Now these other calls simply reduce to:

And let’s see how it works in action:

Apps-MacBook:password-recovery haseeb$ ruby letter_me_now.rb

Current password: 9

Current password: 90

Current password: 90r

Current password: 90rj

Current password: 90rjg

Current password: 90rjgs

Current password: 90rjgsd

Current password: 90rjgsd

Current password: 490rjgsd

Current password: j490rjgsd

Current password: oj490rjgsd

Current password: foj490rjgsd

Current password: efoj490rjgsd

Current password: pefoj490rjgsd

Current password: jpefoj490rjgsd

Current password: fjpefoj490rjgsd

Current password: pfjpefoj490rjgsd

Current password: hpfjpefoj490rjgsd

Current password: 0hpfjpefoj490rjgsd

Current password: 20hpfjpefoj490rjgsd

Current password: 420hpfjpefoj490rjgsd

Current password: g420hpfjpefoj490rjgsd

g420hpfjpefoj490rjgsd

Beautiful. Now let’s just add some more print statements and a bit of extra logging, and we’ll have our finished PasswordCracker.

And now… the magic moment. Let’s swap the stub with the real API and see what happens.

The Moment of Truth

Cross your fingers…

PasswordCracker.new(Api).crack!

(Sped up 3x)

(Sped up 3x)

Boom. 443 iterations.

Tried it out on Reddit, and login was successful.

Wow.

It… actually worked.

Recall our original formula for the number of iterations: A(N/2 + 2). The true password was 22 characters, so our formula would estimate 36 * (22/2 + 2) = 36 * 13 = 468 iterations. Our real password took 443 iterations, so our estimate was within 5% of the observed runtime.

Math.

It works.

Embarrassing support e-mail averted. Reddit rabbit-holing restored. It’s now confirmed: programming is, indeed, magic.

(The downside is I am now going to have to find a new technique to lock myself out of my accounts.)

And with that, I’m gonna get back to my internet rabbit-holes. Thanks for reading, and give it a like if you enjoyed this!

—Haseeb