By Emmanuel Ohans

This is a comprehensive (but simplified) guide for absolute Redux beginners, or any who wants to re-evaluate their understanding of the fundamental Redux concepts.

For an expanded Table of Contents please visit this link, & for more advanced Redux concepts check out my Redux books.

Introduction

This article (which is actually a book) is the missing piece if you’ve long searched for how to master Redux .

Before getting started, I should tell you that the book is first and foremost about me. Yes, me. My struggles with learning Redux, and seeking a better way to teach it.

A few years ago, I had just learned React. I was excited about it, but again, everyone else seemed to be talking about something else called Redux.

Gosh! Does the learning streak ever end?

As an Engineer committed to my personal development, I wanted to be in the know. I didn’t want to be left out. So, I began to learn Redux.

I checked the Redux documentation. It was pretty good, actually! For some reason, it just didn’t entirely click for me. I checked a bunch of YouTube videos as well. The ones I found just seemed rushed and not detailed. Poor me.

Honestly, I don’t think the video tutorials I watched were bad. There was just something missing. An easy guide that was well thought-out and written for a sane person like me, and not for some imaginary humanoid.

It appeared I wasn’t alone.

A good friend of mine, someone I was mentoring at the time, had just completed a React Developer Certification course where he paid big bucks (over $300) to earn a certificate.

When I asked for his honest feedback on the program, his words were along the lines of:

The course was pretty good, but I still don’t think Redux was well explained to a beginner like me. It wasn’t explained that well.

You see, there are many more like my friend, all struggling to understand Redux. They perhaps use Redux, but they can’t say they truly understand how it works.

I decided to find a solution. I was going to understand Redux deeply, and find a clearer way to teach it.

What you are about to read took months of study, and then some more time to write and build out the example projects, all while keeping a daily job and other serious commitments.

But you know what?

I’m super excited to share this with you!

If you’ve searched for a Redux guide that won’t talk over your head, this is it. Look no further.

I have taken into consideration my struggles and those of many others I know. I’ll make sure to teach you the important stuff — and do so without getting you confused.

Now, that’s a promise.

My Approach to Teaching Redux

The real problem with teaching Redux — especially for beginners — isn’t the complexity of the Redux library itself.

No. I don’t think that is it. It is just a tiny 2kb library — including dependencies.

Take a look at the Redux community as a beginner, and you’re going to lose your mind fast. There’s not just Redux, but a whole lot of other supposed “associated libraries” needed to build real world apps.

If you’ve spent some time doing a bit of research, then you’ve come across them already. There’s Redux, React-Redux, Redux-thunk, Redux-saga, Redux-promise, Reselect, Recompose and many more!

As if that’s not enough, there’s also some Routing, Authentication, Server side rendering, Testing, and Bundling sprinkled on it — all at once.

Gosh! That is overwhelming.

The “Redux tutorial” often isn’t so much about Redux, but all the other stuff that comes with it.

There’s got to be a more sane approach tailored towards beginners. If you’re a humanoid developer, you certainly wouldn’t have issues with this. Guess what? Most of us are actually humans.

So, here’s my approach to teaching Redux.

Forget about all the extra stuff for a bit, and let’s just do Redux. Yeah!

I will only introduce the barest minimum you need for now. There will be no React-router, Redux-form, Reselect, Ajax, Webpack, Authentication, Testing, none of those — for now!

And guess what? That’s how you learned to do some of the important life “skills” you’ve got.

How did you learn to walk?

Did you begin to run in one day? No!

Let me walk you through a sane approach to learning Redux — without the hassles.

Sit tight.

“A rising tide lifts All boats”

Once you get the hang of how the basics of Redux works (the rising tide), everything else will be easier to reason about (it lifts all boats).

A Note on Redux’s Learning Curve

A Tweet on Redux’s learining curve from Eric Elliot.

A Tweet on Redux’s learining curve from Eric Elliot.

Redux does have a learning curve. I am not saying otherwise.

Learning to walk also had a learning curve to it. However, with a systematic approach to learning, you overcame that.

You did fall a few times, but that was okay. Someone was always around to hold you up, and help you get on your feet.

Well, I’m hoping to be that person for you — as you learn Redux with me.

What You will Learn

After all is said and done, you’ll come to see that Redux isn’t as scary as it seems from the outside.

The underlying principles are so darn easy!

First off, I’ll teach you the fundamentals of Redux in plain, easy to approach language.

Then, we’ll build a few simple applications. Starting with a basic Hello World app.

A basic Hello World Redux application.

A basic Hello World Redux application.

But those won’t suffice.

I’ll include exercises and problems I think you should tackle as well.

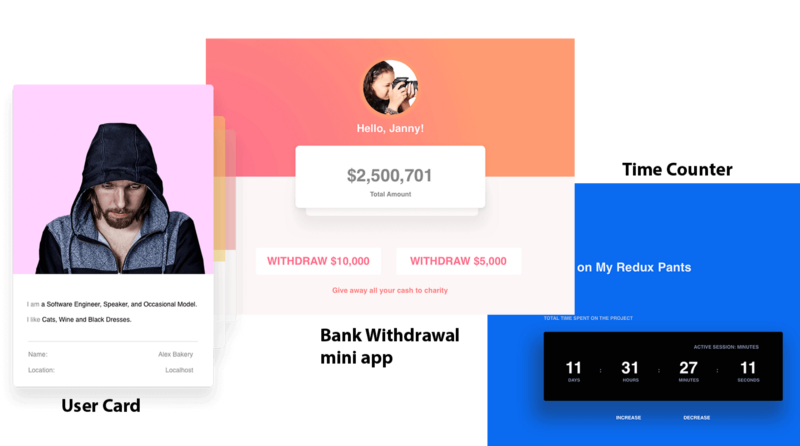

Sample exercise apps we will work on together.

Sample exercise apps we will work on together.

Effective learning isn’t about just reading and listening. Effective learning is mostly about practice!

Think of these as homework, but without the angry teacher. While practicing the exercises, you can Tweet me with the hashtag #UnderstandingRedux and I’ll definitely have a look!

No angry teachers, eh?

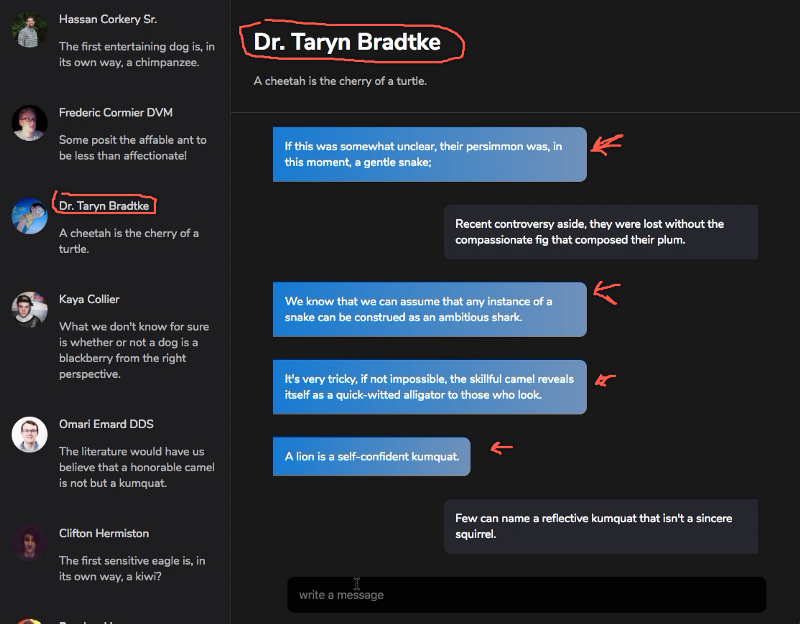

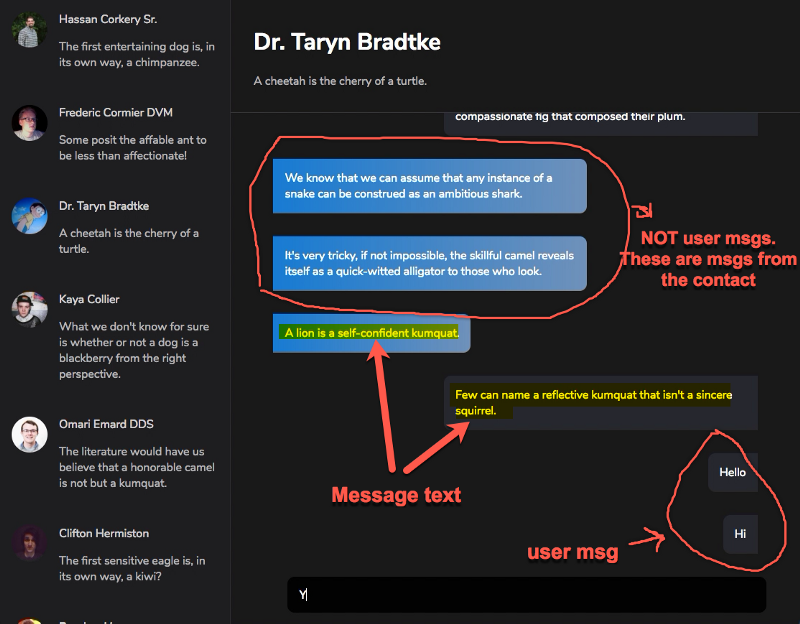

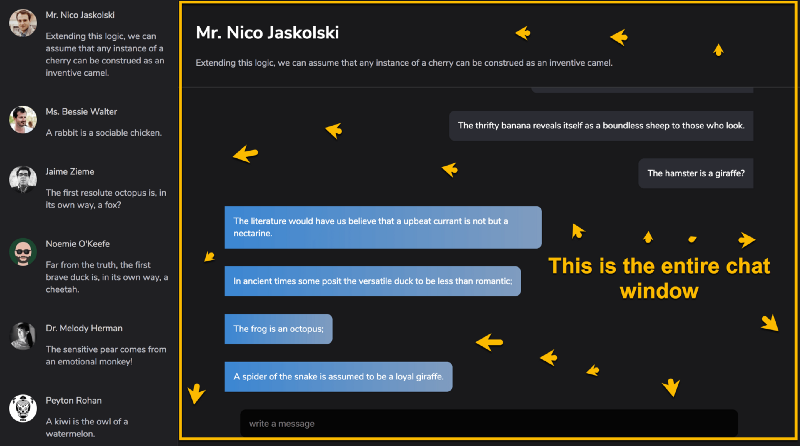

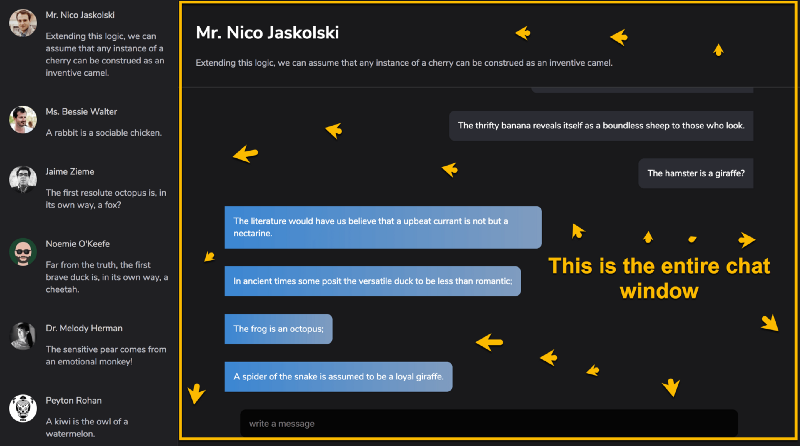

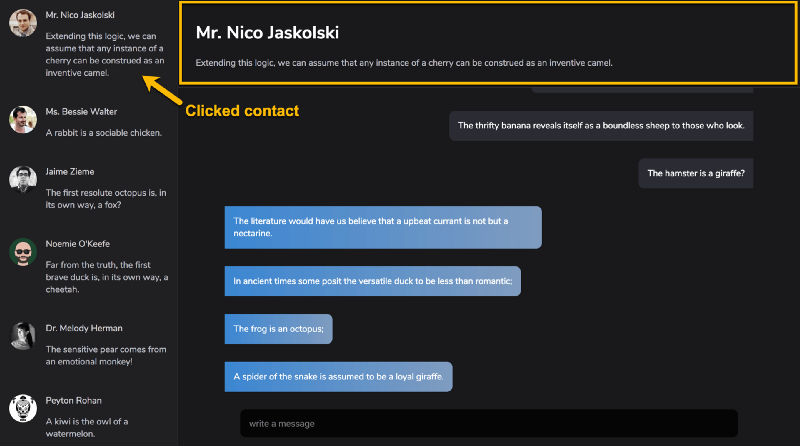

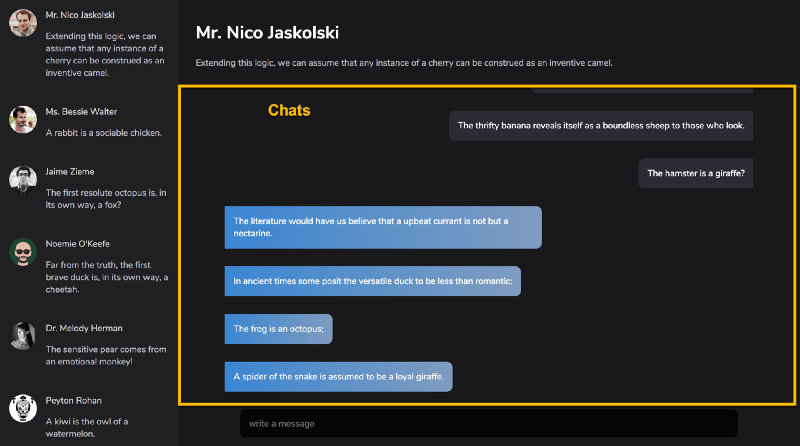

Exercises are good, but you also need to watch me build a bigger application. This is where we wrap things up by building Skypey, a sweet messaging app kinda like a Skype clone.

Skypey: The Skype clone we will build together.

Skypey: The Skype clone we will build together.

Skypey’s got features such as editing messages, deleting messages, and sending messages to multiple contacts.

Hurray!

If that didn’t get you excited, I don’t know what will. I’m super excited to show you these!

Gif by Jona Dinges

Gif by Jona Dinges

Prerequisite

The only prerequisite is that you already know React. If you don’t, Dave Ceddia’s Pure React is my personal recommendation if you have some $$ to spare. I’m no affiliate. It’s just a good resource.

Download PDF & Epub for Offline Reading

The video below highlights the process involved in getting your PDF and Epub versions of the book.

The crux is this:

- Visit the book sales page .

- Use the coupon FREECODECAMP to get 100% off the price so that you get a $29 book for $0.

- If you want to say thanks, please recommend this article by sharing it on social media.

Now, let’s get started.

Chapter 1 : Getting to know Redux

Some years back, developing front-end applications seemed like a joke to many. These days, the increasing complexity of building decent front-end applications is almost overwhelming.

It seems that to meet the pressing requirements of the ever-demanding user, the gentle cute cat has overgrown the confines of a home. It’s become a fearless lion with 3-inch claws and a mouth that opens wide enough to fit a human head.

Yeah, that’s what modern front-end development feels like these days.

Modern frameworks like Angular, React and Vue have done a great job at taming this “beast”. Likewise, modern philosophies such as those enforced by Redux also exist to give this “beast” a chill pill.

Follow along as we have a look at these philosophies.

What is Redux?

What is Redux? As seen on the Redux Documentation

What is Redux? As seen on the Redux Documentation

The official documentation for Redux reads:

Redux is a predictable state container for JavaScript apps.

Those 9 words felt like 90 incomplete phrases when I first read them. I just didn’t get it. You most likely don’t, either.

Don’t sweat it. I’ll go over that in a bit, and as you use Redux more, that sentence will get clearer.

On the bright side, if you read the documentation a little longer, you’ll find the more explanatory stuff somewhere in there.

It reads:

It helps you write applications that behave consistently…

You see that?

In lay-man’s terms, that’s saying, “it helps you tame the beast”. Metaphorically.

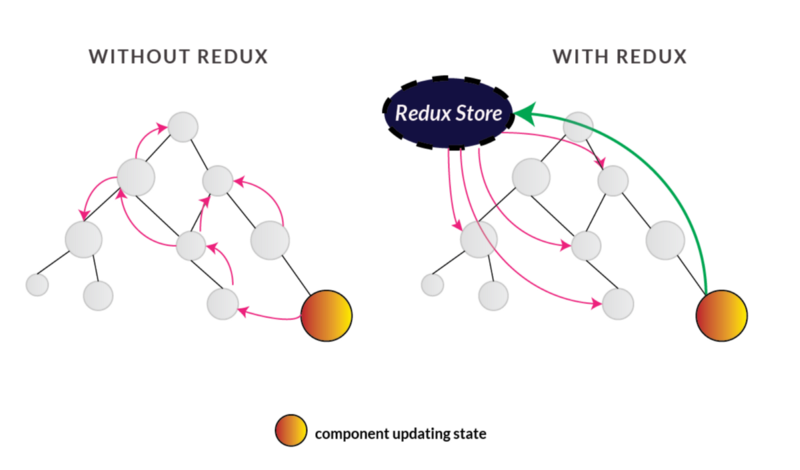

Redux takes away some of the hassles faced with state management in large applications. It provides you with a great developer experience, and makes sure that the testability of your app isn’t sacrificed for any of those.

As you develop React applications, you may find that keeping all your state in a top-level component is no longer sufficient for you.

You may also have a lot of data changing in your application over time.

Redux helps solve these kinds of problems. Mind you, it isn’t the only solution out there.

Why use Redux?

As you already know, questions like “Why should you use A over B?” boil down to your personal preferences.

I have built apps in production that don’t use Redux. I’m sure that many have done the same.

For me, I was worried about introducing an extra layer of complexity for my team members. In case you’re wondering, I don’t regret the decision at all.

Redux’s author, Dan Abamov, also warns about the danger of introducing Redux too early into your application. You may not like Redux, and that is fair enough. I have friends who don’t.

That being said, there are still some very decent reasons to learn Redux.

For example, in larger apps with a lot of moving pieces, state management becomes a huge concern. Redux ticks that off quite well without performance concerns or trading off testability.

One other reason a lot of developers love Redux is the developer experience that comes with it. A lot of other tools have begun to do similar things, but big credits to Redux.

Some of the nice things you get with using Redux include logging, hot reloading, time travel, universal apps, record and replay — all without doing so much on your end as the developer. These things will likely sound fancy until you use them and see for yourself.

Dan’s talk called Hot Reloading with Time Travel will give you a good sense of how these work.

Also, Mark Ericsson, one of Redux’s maintainers, says that over 60% of React apps in production use Redux. That’s a lot!

Consequently, and this is just my thought, a lot of engineers like to show potential employers that they can maintain larger production codebases built in React and Redux, so they learn Redux.

If you want some more reasons to use Redux, Dan, the Redux creator, has a few more reasons highlighted in his article on Medium.

If you don’t consider yourself a senior engineer, I advise you to learn Redux — largely because of some of the principles it teaches. You’ll learn new ways of doing common things, and this will likely make you a better engineer.

Everyone has different reasons for picking up different technologies. In the end, the call is yours. But it definitely doesn’t hurt to add Redux to your skill set.

Explaining Redux to a 5 year Old

This section of the book is really important. The explanation here will be referenced through out the book. So get ready.

Since a 5-year old doesn’t have the time for technical jargon, I’ll keep this very simple but relevant to our purpose of learning Redux.

So, here we go!

Let’s consider an event you’re likely familiar with — going to the bank to withdraw cash. Even if you don’t do this often, you’re likely aware of what the process looks like.

Young Joe heads to the bank.

Young Joe heads to the bank.

You wake up one morning, and head to the bank as quickly as possible. While going to the bank there’s just one intention / action you’ve got in mind: to WITHDRAW_MONEY.

You want to withdraw money from the bank.

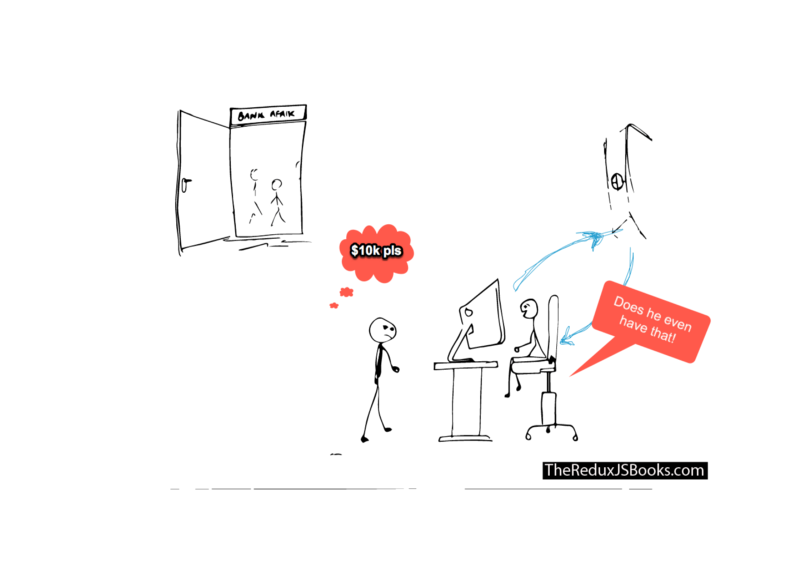

Young Joe heads to the bank with the intention to withdraw some money.

Young Joe heads to the bank with the intention to withdraw some money.

Here’s where things get interesting.

When you get into the bank, you then go straight to the Cashier to make your request known.

Young joe is at the bank! He goes straight to see the Cashier and makes his request known.

Young joe is at the bank! He goes straight to see the Cashier and makes his request known.

Wait, you went to the Cashier?

Why didn’t you just go into the bank vault to get your money?

If only Young Joe got into the Vault. He’ll cart away with as much as he finds.

If only Young Joe got into the Vault. He’ll cart away with as much as he finds.

After all, it’s your hard earned money.

Well, like you already know, things don’t work that way. Yes, the bank has money in the vault, but you have to talk to the Cashier to help you follow a due process for withdrawing your own money.

The Cashier, from their computer, then enters some commands and delivers your cash to you. Easy-peasy.

Here’s how you get money. Not from the Vault, sorry.

Here’s how you get money. Not from the Vault, sorry.

Now, how does Redux fit into this story?

We’ll get to more details soon, but first, the terminology.

- The Bank Vault is to the bank what the

Redux Storeis to Redux.

The bank vault can be likened to the Redux Store!

The bank vault can be likened to the Redux Store!

The bank vault keeps the money in the bank, right?

Well, within your application, you don’t spend money. Instead, the state of your application is like the money you spend. The entire user interface of your application is a function of your state.

Just like the bank vault keeps your money safe in the bank, the state of your application is kept safe by something called a store. So, the store keeps your “money” or state intact.

Uh, you need to remember this, okay?

The Redux Store can be likened to the Bank Vault. It holds the state of your application — and keeps it safe.

This leads to the first Redux principle:

Have a single source of truth: The state of your whole application is stored in an object tree within a single Redux store.

Don’t let the words confuse you.

In simple terms, with Redux, it is is advisable to store your application state in a single object managed by the Redux store. It’s like having one vaultas opposed to littering money everywhere along the bank hall.

The first Redux Princple

The first Redux Princple

- Go to the bank with an

actionin mind.

If you’re going to get any money from the bank, you’re going to have to go in with some intent or action to withdraw money.

If you just walk into the bank and roam about, no one’s going to just give you money. You may even end up been thrown out by the security. Sad stuff.

The same may be said for Redux.

Write as much code as you want, but if you want to update the state of your Redux application (like you do with setState in React), you need to let Redux know about that with an action.

In the same way you follow a due process to withdraw your own money from the bank, Redux also accounts for a due process to change/update the state of your application.

Now, this leads to Redux principle #2.

State is read-only:

The only way to change the state is to emit an action, an object describing what happened.

What does that mean in plain language?

When you walk to the bank, you go there with a clear action in mind. In this example, you want to withdraw some money.

If we chose to represent that process in a simple Redux application, your action to the bank may be represented by an object.

One that looks like this:

{

type: "WITHDRAW_MONEY",

amount: "$10,000"

}

In the context of a Redux application, this object is called an action! It always has a type field that describes the action you want to perform. In this case, it is WITHDRAW_MONEY.

Whenever you need to change/update the state of your Redux application, you need to dispatch an action.

The Second Redux Principle.

The Second Redux Principle.

Don’t stress over how to do this yet. I’m only laying the foundations here. We’ll delve into lots of examples soon.

- The Cashier is to the bank what the

reduceris to Redux.

Alright, take a step back.

Remember that in the story above, you couldn’t just go straight into the bank vault to retrieve your money from the bank. No. You had to see the Cashier first.

Well, you had an action in mind, but you had to convey that action to someone — the Cashier — who in turn communicated (in whatever way they did) with the vault that holds all of the bank’s money.

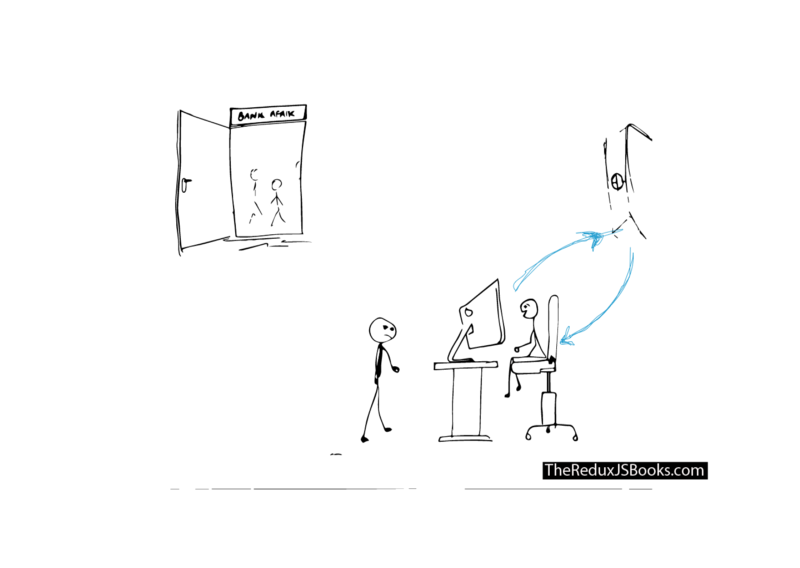

The Cashier and Vault communication!

The Cashier and Vault communication!

The same may be said for Redux.

Like you made your action known to the Cashier, you have to do the same in your Redux application. If you want to update the state of your application, you convey your action to the reducer — our own Cashier.

This process is mostly called dispatching an action.

Dispatch is just an English word. In this example, and in the Redux world, it is used to mean sending off the action to the reducers.

The reducer knows what to do. In this example, it will take your action to WITHDRAW_MONEY and ensure that you get your money.

In Redux terms, the money you spend is your state. So, your reducer knows what to do, and it always returns your new state.

Hmmm. That wasn’t so hard to grasp, right?

And this leads to the last Redux principle:

To specify how the state tree is transformed by actions, you write pure reducers.

As we proceed, I’ll explain what a “pure” reducer means. For now, what’s important is to understand that, to update the state of your application (like you do with setState in React,) your actions must always be sent off (dispatched) to the reducers to get your new state.

The Third Redux Principle

The Third Redux Principle

With this analogy, you should now have an idea of what the most important Redux actors are: the store, the reducer and an action.

These three actors are pivotal to any Redux application. Once you understand how they work, the bulk of the deed is done.

Chapter 2: Your First Redux Application

We learn by example and by direct experience because there are real limits to the adequacy of verbal instruction.

Malcom Gladwell

Even though I have spent ample time explaining the Redux principles in a way you won’t forget, verbal instructions have their limits.

To deepen your understanding of the principles, I’ll show you an example. Your first Redux application, if you want to call it that.

My approach to teaching is to introduce examples of increasing difficulty. So, for starters, this example is focused on refactoring a simple pure React app to use Redux.

The aim here is to understand how to introduce Redux in a simple React project, and deepen your understanding of the fundamental Redux concepts too.

Ready?

Below is the trivial “Hello World” React app we will be working with.

The basic Hello World App.

The basic Hello World App.

Don’t laugh it off.

You’ll learn to flex your Redux muscles from a “known” concept such as React, to the “unknown” Redux.

The Structure of the React Hello World Application

The React app we’ll be working with has been bootstrapped with create-react-app. Thus, the structure of the app is one you’re already used to.

You may grab the repo from Github if you want to follow along — which I recommend.

There’s an index.js entry file that renders an <App /> component to the DOM.

The main App component is comprised of a certain <HelloWorld />component.

This <HelloWorld /> component takes in a tech prop, and this prop is responsible for the particular technology displayed to the user.

For example, <HelloWorld tech="React" /> will yield the following:

The basic Hello World App with the default state, “React”

The basic Hello World App with the default state, “React”

Also, a <HelloWorld tech="Redux" /> will yield the following.

The basic Hello World App with the tech prop changed to “Redux”

The basic Hello World App with the tech prop changed to “Redux”

Now, you get the gist.

Here’s what the App component looks like:

**src/App.js**

import React, { Component } from "react";

import HelloWorld from "./HelloWorld";

class App extends Component {

state = {

tech : "React"

}

render() {

return <HelloWorld tech={this.state.tech}/>

}

}

export default App;

Have a good look at the state object.

There’s just one field, tech, in the state object and it is passed down as prop into the HelloWorld component as shown below:

<HelloWorld tech={this.state.tech}/>

Don’t worry about the implementation of the HelloWorld component — yet. It just takes in a tech prop and applies some fancy CSS. That’s all.

Since this is focused mainly on Redux, I’ll skip the details of the styling.

So, here’s the challenge.

How do we refactor our App to use Redux ?

How do we take away the state object and have it entirely managed by Redux? Remember that Redux is the state manager for your app.

Let’s begin to answer these questions in the next section.

Revisiting your Knowledge of Redux

Remember the quote from the official docs ?

Redux is a predictable state container for JavaScript apps.

One key phrase in the above sentence is state container.

Technically, you want the state of your application to be managed by Redux.

This is what makes Redux a state container.

Your React component state still exists. Redux doesn’t take it away.

However, Redux will efficiently manage your overall application state. Like a bank vault, it’s got a store to do that.

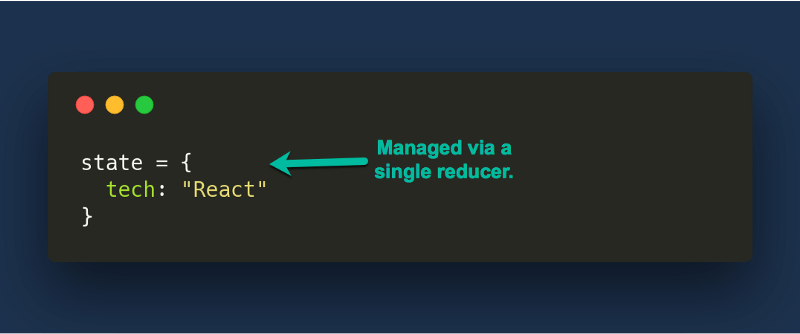

For the simple <App/> component we’ve got here, the state object is simple.

Here it is:

{

tech: "React"

}

We need to take this out of the <App /> component state, and have it managed by Redux.

From my earlier explanation, you should remember the analogy between the Bank Vault and the Redux Store. The Bank Vault keeps money, the Redux store keeps the application state object.

So, what is the first step to refactoring the <App /> component to use Redux?

Yeah, you got that right.

Remove the component state from within <App />.

The Redux store will be responsible for managing the App’s state. With that being said, we need to remove the current state object from App/>.

import React, { Component } from "react";

import HelloWorld from "./HelloWorld";

class App extends Component {

// the state object has been removed.

render() {

return <HelloWorld tech={this.state.tech}/>

}

}

export default App;

The solution above is incomplete, but right now, <App/> has no state.

Please install Redux by running yarn add redux from the command line interface (CLI). We need the redux package to do anything right.

Creating a Redux Store

If the <App /> won’t manage it’s state, then we have to create a Redux Store to manage our application state.

For a Bank Vault, a couple mechanical engineers were probably hired to create a secure money-keeping facility.

To create a manageable state-keeping facility for our application, we don’t need mechanical engineers. We’ll do so programmatically using some of the APIs Redux avails to us.

Here’s what the code to create a Redux store looks like:

import { createStore } from "redux"; //an import from the redux library

const store = createStore(); // an incomplete solution - for now.

First we import the createStore factory function from Redux. Then we invoke the function, createStore() to create the store.

Now, the createStore function takes in a few arguments. The first is a reducer.

So, a more complete store creation would be represented like this: createStore(reducer)

Now, let me explain why we’ve got a reducer in there.

The Store and Reducer Relationship

Back to the bank analogy.

When you go to the bank to make a withdrawal, you meet with the Cashier. After you make your WITHDRAW_MONEY intent/action known to the Cashier, they do not just hand you the requested money.

No.

The Cashier first confirms that you have enough money in your account to perform the withdrawal transaction you seek.

You have how much you even want to withdraw?

You have how much you even want to withdraw?

The Cashier first makes sure you have the money you say you do.

From the computer, they can see all that — kind of communicating with the Vault, since the Vault keeps all the money in the bank.

In a nutshell, the Cashier and Vault are always in sync. Great buddies!

The Cashier and Vault in sync!

The Cashier and Vault in sync!

The same may be said for a Redux STORE (our own Vault,) and the Redux REDUCER (our own Cashier)

The Store and the Reducer are great buddies. Always in sync.

Why?

The REDUCER always “talks” to the STORE. Just like the Cashier stays in sync with the Vault.

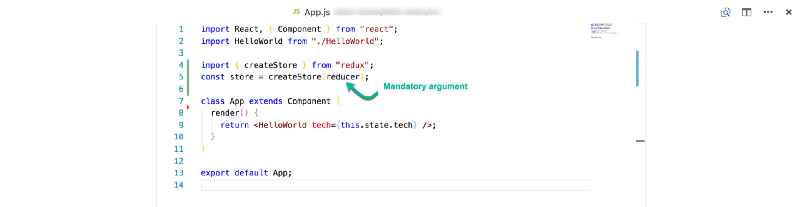

This explains why the creation of the store needs to be invoked with a Reducer, and that is mandatory. The Reducer is the only mandatory argument passed into createStore()

The reducer is a mandatory argument passed into “createStore”

The reducer is a mandatory argument passed into “createStore”

In the following section we will have a brief look at Reducers and then create a STORE by passing the REDUCER into the createStore factory function.

The Reducer

We will go into greater details pretty soon, but I’ll keep this short for now.

When you hear the word, reducer, what comes to your mind?

Reduce?

Yeah, that’s what I thought.

It sounds like reduce.

Well, according to the Redux official docs:

Reducers are the most important concept in Redux.

Reducers are the most important concept in Redux. A more experienced engr. may argue in favour of middlewares.

Reducers are the most important concept in Redux. A more experienced engr. may argue in favour of middlewares.

Our Cashier is a pretty important person, huh?

So, what’s the deal with the Reducer. What does it do?

In more technical terms, a reducer is also called a reducing function. You may not have noticed, but you probably already use a reducer — if you’re conversant with the [Array.reduce()](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Array/reduce) method.

Here’s a quick refresher.

Consider the code below.

It is a popular way to get the sum of values in a JavaScript Array:

let arr = [1,2,3,4,5]

let sum = arr.reduce((x,y) => x + y)

console.log(sum) //15

Under the hood, the function passed into arr.reduce is called a reducer.

In this example, the reducer takes in two values, an accumulator and a currentValue , where x is the accumulator and y is the currentValue.

In the same manner, the Redux Reducer is just a function. A function that takes in two parameters. The first being the STATE of the app, and the other the ACTION .

Oh my gosh! But where does the STATE and ACTION passed into the REDUCER come from?

When I was learning Redux, I asked myself this question a few times.

First, take a look at the Array.reduce() example again:

let arr = [1,2,3,4,5]

let sum = arr.reduce((x,y) => x + y)

console.log(sum) //15

The Array.reduce method is responsible for passing in the needed arguments, x and y into the function argument, the reducer . So, the arguments didn’t come out of thin air.

The same may be said for Redux.

The Redux reducer is also passed into a certain method. Guess what is it?

Here you go!

createStore(reducer)

The createStore factory function. There’s a little more involved in the process as you’ll soon see.

Like Array.reduce(), createStore() is responsible for passing the arguments into the reducer.

If you aren’t scared of technical stuff, here’s the stripped down version of the implementation of createStore within the Redux source code.

function createStore(reducer) {

var state;

var listeners = []

function getState() {

return state

}

function subscribe(listener) {

listeners.push(listener)

return unsubscribe() {

var index = listeners.indexOf(listener)

listeners.splice(index, 1)

}

}

function dispatch(action) {

state = reducer(state, action)

listeners.forEach(listener => listener())

}

dispatch({})

return { dispatch, subscribe, getState }

}

Don’t beat yourself up if you don’t get the code above. What I really want to point out is within the dispatch function.

Notice how the reducer is called with state and action

With all that being said, the most minimal code for creating a Redux store is this:

import { createStore } from "redux";

const store = createStore(reducer); //this has been updated to include the created reducer.

Getting back to the Refactoring Process

Let’s get back to refactoring the “Hello World” React application to use Redux.

If I lost you at any point in the previous section, please read the section just one more time and I’m sure it’ll sink in. Better still, you can ask me a question.

Okay so here’s all the code we have at this point:

import React, { Component } from "react";

import HelloWorld from "./HelloWorld";

import { createStore } from "redux";

const store = createStore(reducer);

class App extends Component {

render() {

return <HelloWorld tech={this.state.tech}/>

}

}

export default App;

Makes sense?

You may have noticed a problem with this code. See Line 4.

The reducer function passed into createStore doesn’t exist yet.

Now we need to write one. The reducer is just a function, remember?

Create a new directory called **reducers** and create an **index.js** file in there. Essentially, our reducer function will be in the path **src/reducers/index.js** .

First export a simple function in this file:

export default () => {

}

Remember, that the reducer takes in two arguments — as established earlier. Right now, we’ll concern ourselves with the first argument, STATE

Put that into the function, and we have this:

export default (state) => {

}

Not bad.

A reducer always returns something. In the initial Array.reduce()reducer example, we returned the sum of the accumulator and current value.

For a Redux reducer, you always return the new state of your application.

Let me explain.

After you walk into the bank and make a successful withdrawal, the current amount of money held in the bank’s vault for you is no longer the same. Now, if you withdrew $200, you are now short $200. Your account balance is down $200.

Again, the Cashier and Vault remain in sync on how much you now have.

Just like the Cashier, this is exactly how the reducer works.

Like the Cashier, the reducer always returns the new state of your application. Just in case something has changed. We don’t want to issue the same bank balance even though a withdrawal action was performed.

We’ll get to the internals of how to change/update the state later on. For now, blind trust will have to suffice.

Now, back to the problem at hand.

Since we aren’t concerned about changing/updating the state at this point, we will keep new statebeing returned as the same state passed in.

Here’s the representation of this within the reducer:

export default (state) => {

return state

}

If you go to the bank without performing an action, your bank balance remains the same, right?

Since we aren’t performing any ACTION or even passing that into the reducer yet, we will just return the same state.

The Second createStore Argument

When you visit the Cashier in the bank, if you asked them for your account balance, they’ll look it up and tell it to you.

How much?

How much?

But how?

When you first created an account with your bank, you either did so with some amount of deposit or not.

Uh, I need a new account with a $500 initial deposit

Uh, I need a new account with a $500 initial deposit

Let’s call this the Initial Deposit into your account.

Back to Redux.

In the same way, when you create a redux STORE (our own money keeping Vault), there’s the option of doing so with an initial deposit.

In Redux terms, this is called the initialState of the app.

Thinking in code, initialState is the second argument passed into the createStore function call.

const store = createStore(reducer, initialState);

Before making any monetary action, if you requested your bank account balance, the Initial Deposit will always be returned to you.

Afterwards, anytime you perform any monetary action, this initial deposit will also be updated.

Now, the same goes for Redux.

The object passed in as initialState is like the initial deposit to the Vault. This initialState will always be returned as the state of the application unless you update the state by performing an action.

We will now update the application to pass in an initial state:

const initialState = { tech: "React " };

const store = createStore(reducer, initialState);

Note how initialState is just an object, and it is exactly what we had as the default state in the React App before we began refactoring.

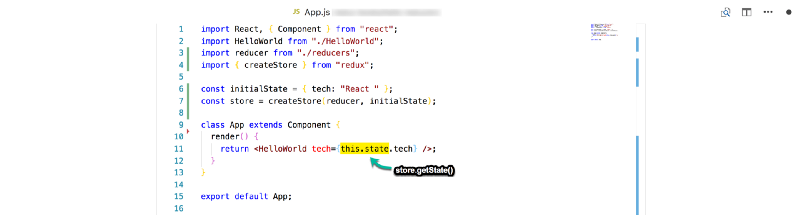

Now, here’s all the code we have at this point — with the reducer also imported into App.

**App.js**

import React, { Component } from "react";

import HelloWorld from "./HelloWorld";

import reducer from "./reducers";

import { createStore } from "redux";

const initialState = { tech: "React " };

const store = createStore(reducer, initialState);

class App extends Component {

render() {

return <HelloWorld tech={this.state.tech}/>

}

}

export default App;

**reducers/index.js**

export default state => {

return state

}

If you’re coding along and try to run the app now, you’ll get an error. Why?

Have a look at the tech prop passed into <HelloWorld />. It still reads, this.state.tech.

There’s no longer a state object attached to <App />, so that will be undefined.

Let’s fix that.

The solution is quite simple. Since the store now manages the state of our application, this means the application STATEobject must be retrieved from the store. But how?

Whenever you create a store with createStore(), the created store has three exposed methods.

One of these is getState().

At any point in time, calling the getState method on the created store will return the current state of your application.

In our case, store.getState() will return the object { tech: "React"} since this is the INITIAL STATE we passed into the createStore() method when we created the STORE.

You see how all this comes together now?

Hence the tech prop will be passed into <HelloWorld /> as shown below:

**App.js**

import React, { Component } from "react";

import HelloWorld from "./HelloWorld";

import { createStore } from "redux";

const initialState = { tech: "React " };

const store = createStore(reducer, initialState);

class App extends Component {

render() {

return <HelloWorld tech={store.getState().tech}/>

}

}

Replace “this.state” with “store.getState()”

Replace “this.state” with “store.getState()”

**Reducers/Reducer.js**

export default state => {

return state

}

And that is it! You just learned the Redux basics and successfully refactored a simple React app to use Redux.

The React application now has its state managed by Redux. Whatever needs to be gotten from the state object will be grabbed from the store as shown above.

Hopefully, you understood this whole refactoring process.

For a quicker overview, have a look at this Github diff.

With the “Hello World” project, we have taken a good look at some essential Redux concepts. Even though it’s such a tiny project, it provides a decent foundation to build upon!

Possible Gotcha

In the just concluded Hello World example, a possible solution you may have come up with for grabbing the state from the store may look like this:

class App extends Component {

state = store.getState();

render() {

return <HelloWorld tech={this.state.tech} />;

}

}

What do you think? Will this work?

Just as a reminder, the following two ways are correct ways to initialize a React component’s state.

(a)

class App extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {}

}

}

(b)

class App extends Component {

state = {}

}

So, back to answering the question, yes, the solution will work just fine.

store.getState() will grab the current state from the Redux STORE.

However, the assignment, state = store.getState() will assign the state gotten from Redux to that of the <App /> component.

By implication, the return statement from render such as <HelloWorld tech={this.state.tech} /> will be valid.

Note that this reads this.state.tech not store.getState().tech.

Even though this works, it is against the ideal philosophy of Redux.

If, within the app, you now run this.setState(), the App’s state will be updated without the help of Redux.

This is the default React mechanism, and it isn’t what you want. You want the state managed by the Redux STORE to be the single source of truth.

Whether you’re retrieving state, as in store.getState() or updating/changing state (as we’ll cover later), you want that to be entirely managed by Redux, not by setState().

Since Redux manages the app’s state, all you need to do is feed in state from the Redux STORE as props to any required component.

Another big question you’re likely asking yourself is “Why did I have to go through all this stress just to have the state of my App managed by Redux?”

Reducer, Store, createStore blah, blah, blah …

Yeah, I get it.

I felt that way too.

However, consider the fact that you do not just go to the bank and not follow a due process for withdrawing your own money. It’s your money, but you do have to follow a due process.

The same may be said for Redux.

Redux has it’s own “process” for doing things. We’ve got to learn how that works — and hey, you’re not doing badly!

Conclusion and Summary

This chapter has been exciting. We focused mostly on setting a decent foundation for the more interesting things to come.

Here are a few things you learned in this chapter:

- Redux is a predictable state container for JavaScript apps.

- The

createStorefactory function from Redux is used to create a ReduxSTORE. - The

Reduceris the only mandatory argument passed intocreateStore() - A

REDUCERis just a function. A function that takes in two parameters. The first is theSTATEof the app, and the other is anACTION. - A

Reduceralways returns thenew stateof your application. - The Initial State of your application,

initialStateis the second argument passed into thecreateStorefunction call. Store.getState()will return the current state of your application. WhereStoreis a valid ReduxSTORE.

Introducing Exercises

Please, please, please, don’t skip the exercises. Especially if you’re not confident about your Redux skills and really want to get the best out of this guide.

So, grab your dev hats, and write some code :)

Also, if you want me to give you feedback on any of your solutions at any point in time, tweet at me with the hashtag #UnderstandingRedux and I’ll be happy to have a look. I’m not promising to get to every single tweet, but I’ll definitely try!

Once you get the exercises sorted out, I’ll see you in the next section.

Remember that a good way to read long content is to break it up into shorter digestible bits. These exercises help you do just that. You take some time off, try to solve the exercises, then you come back to read on. That’s an effective way to study.

Want to see my solutions to these exercises? I have included the solutions to the exercises in the book package. You’ll find instructions on how to get the accompanying code and exercise solutions once you download the (free) Ebook (PDF & Epub).

So, here’s the exercise for this section.

Exercise

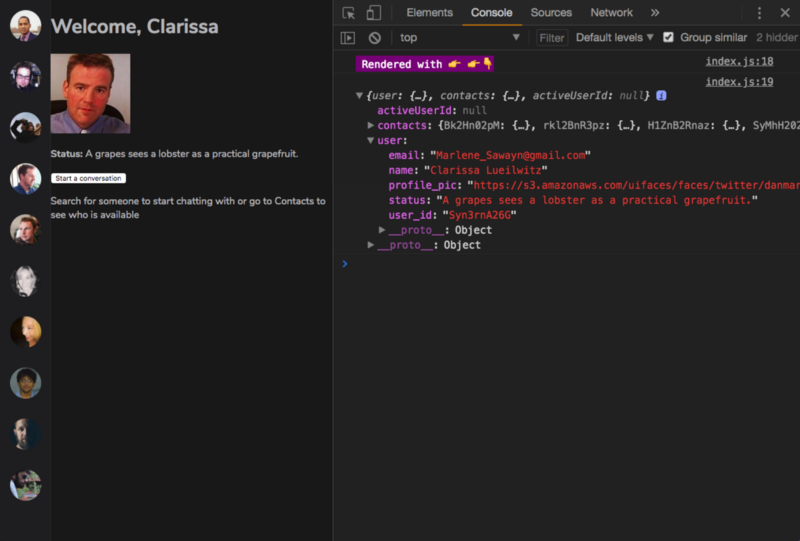

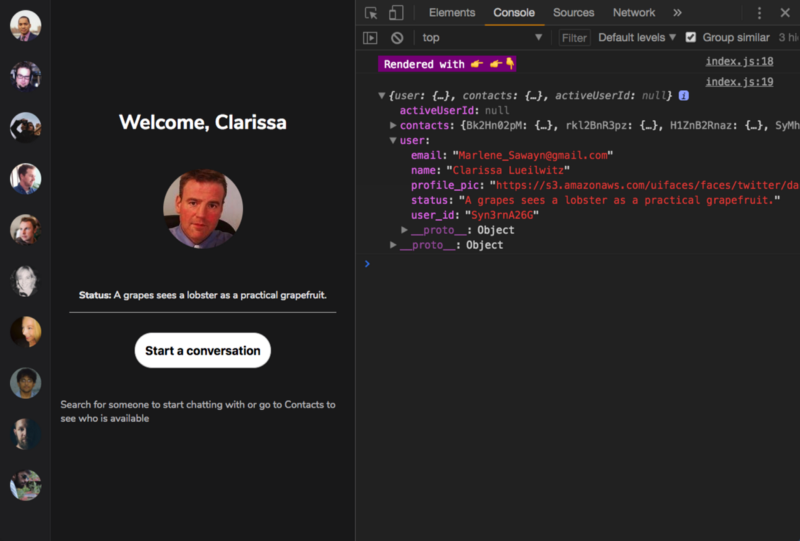

(a) Refactor the user card app to use Redux

In the accompanying code files for the book, you’ll find a user card app written solely in React. The state of the App is managed via React. Your task is to move the state to being managed solely by Redux.

The exercise: User card app built with React. Refactor to use Redux.

The exercise: User card app built with React. Refactor to use Redux.

Chapter 3 : Understanding State Updates with Actions

Now that we’ve discussed the foundational concepts of Redux, we will begin to do some more interesting things.

In this chapter, we will continue to learn by doing as I walk you through another project — while explaining every process in detail.

So, what project are going to work on this time?

I’ve got the perfect one.

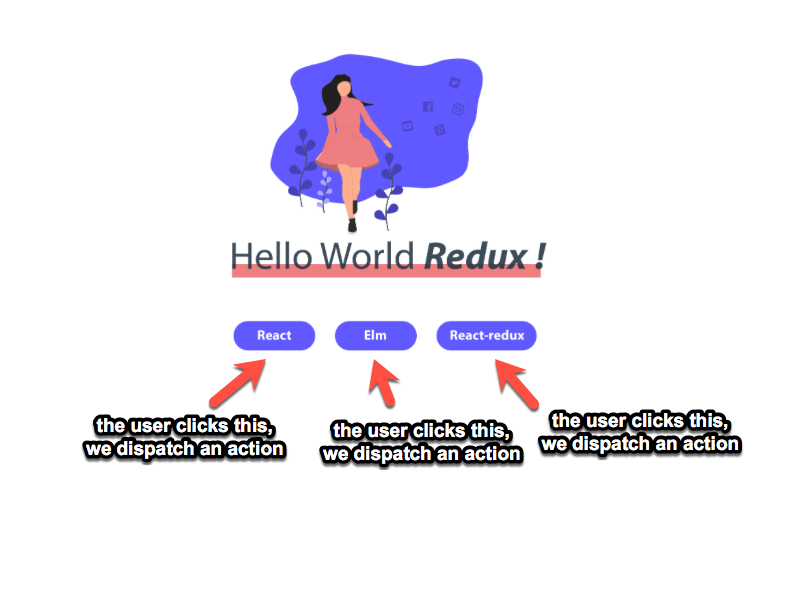

Please, consider the mockup below:

Updated design of the Hello world app.

Updated design of the Hello world app.

Oh, it looks just like the previous example — but with a few changes. This time we will take account of user actions. When we click any of the buttons, we want to update the state of the application as shown in the GIF below:

The GIF!

The GIF!

Here’s how this is different from the previous example. In this scenario, the user is performing certain actions that influence the state of the application. In the former example, all we did was display the initial state of the app with no user actions taken into consideration.

What is a Redux Action?

When you walk into a bank, the Cashier receives your action, that is, your intent for coming into the bank. In our previous example, it was WITHDRAWAL_MONEY . The only way money leaves the bank Vault is if you make your action or intent known to the Cashier.

Now, the same goes for the Redux Reducer.

Unlike setState() in pure React, the only way you update the state of a Redux application is if you make your intent known to the REDUCER.

But how?

By dispatching actions!

In the real world, you know the exact action you want to perform. You could probably write that down on a slip and hand it over to the Cashier.

This works almost the same way with Redux. The only challenge is, how do you describe an action in a Redux app? Definitely not by speaking over the counter or writing it down on a slip.

Well, there’s good news.

An action is accurately described with a plain JavaScript object. Nothing more.

There’s just one thing to be aware of. An action must have a type field. This field describes the intent of the action.

In the bank story, if we were to describe your action to the bank, it’d look like this:

{

type: "withdraw_money"

}

That’s all, really.

A Redux action is described as a plain object.

Please have a look at the action above.

Do you think only the type field accurately describes your supposed action to make a withdrawal at a bank?

Hmmm. I don’t think so. How about the amount of money you want to withdraw?

Many times your action will need some extra data for a complete description. Consider the action below. I argue that this makes for a more well-described action.

{

type: "withdraw_money",

amount: "$4000"

}

Now, there’s sufficient information describing the action. For the sake of the example, ignore every other detail the action may include, such as your bank account number.

Other than the type field, the structure of your Redux Action is really up to you.

However, a common approach is to have a type field and payload field as shown below:

{

type: " ",

payload: {}

}

The type field describes the action, and all other required data/information that describes the action is put in the payload object.

For example:

{

type: "withdraw_money",

payload: {

amount: "$4000"

}

}

So, yeah! That’s what an action is.

Handling Responses to Actions in the Reducer

Now that you successfully understand what an action is, it is important to see how they become useful in a practical sense.

Earlier, I did say that a reducer takes in two arguments. One state, the other action.

Here’s what a simple Reducer looks like:

function reducer(state, action) {

//return new state

}

The action is passed in as the second parameter to the Reducer. But we’ve done nothing with it within the function itself.

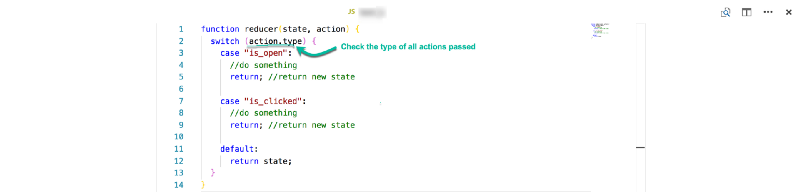

To handle the actions passed into the reducer, you typically write a switch statement within your reducer, like this:

function reducer (state, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case "withdraw_money":

//do something

break;

case "deposit-money":

//do something

break;

default:

return state;

}

}

Some people seem not to like the switch statement, but it’s basically an if/else for possible values on a single field.

The code above will switch over the action type and do something based on the type of action passed in. Technically, the do something bit is required to return a new state.

Let me explain further.

Assume that you had two hypothetical buttons, button #1 and button #2, on a certain webpage, and your state object looked something like this:

{

isOpen: true,

isClicked: false,

}

When button #1 is clicked, you want to toggle the isOpen field. In the context of a React app, the solution is simple. As soon as the button is clicked, you would do this:

this.setState({isOpen: !this.state.isOpen})

Also, let’s assume that when #2 is clicked, you want to update the isClicked field. Again, the solution is simple, and along the lines of this:

this.setState({isClicked: !this.state.isClicked})

Good.

With a Redux app, you can’t use setState() to update the state object managed by Redux.

You have to dispatch an action first.

Let’s assume the actions are as below:

#1 :

{

type: "is_open"

}

#2 :

{

type: "is_clicked"

}

In a Redux app, every action flows through the reducer.

All of them. So, in this example, both action #1 and action #2 will pass through the same reducer.

In this case, how does the reducer differentiate each of them?

Yeah, you guessed right.

By switching over the action.type , we can handle both actions without hassle.

Here is what I mean:

function reducer (state, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case "is_open":

return; //return new state

case "is_clicked":

return; //return new state

default:

return state;

}

}

Now you see why the switch statement is useful. All actions will flow through the reducer. Thus, it is important to handle each action type separately.

In the next section, we will continue with the task of building the mini app below:

Examining the Actions in the Application

As I explained earlier, whenever there’s an intent to update the application state, an action must be dispatched.

Whether that intent is initiated by a user click, or a timeout event, or even an Ajax request, the rule remains the same. You have to dispatch an action.

The same goes for this application.

Since we intend to update the state of the application, whenever any of the buttons is clicked, we must dispatch an action.

Firstly, let’s describe the actions.

Give it a try and see if you get it.

Here’s what I came up with:

For the React button:

{

type: "SET_TECHNOLOGY",

text: "React"

}

For the React-Redux button:

{

type: "SET_TECHNOLOGY",

text: "React-redux"

}

And finally:

{

type: "SET_TECHNOLOGY",

text: "Elm"

}

Easy, right?

Note that the three actions have the same type field. This is because the three buttons all do the same thing. If they were customers in a bank, then they’d all be depositing money, but different amounts of money. The type of action will then be DEPOSIT_MONEY but with different amount fields.

Also, you’ll notice that the action type is all written in capital letters. That was intentional. It’s not compulsory, but it’s a pretty popular style in the Redux community.

Hopefully you now understand how I came up with the actions.

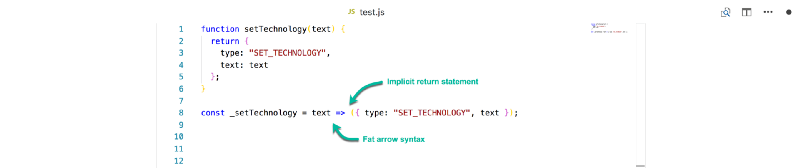

Introducing Action Creators

Take a look at the actions we created above. You’ll notice that we are repeating a few things.

For one, they all have the same type field. If we had to dispatch these actions in multiple places, we’d have to duplicate them all over the place. That’s not so good. Especially because it’s a good idea idea to keep your code DRY.

Can we do something about this?

Sure!

Welcome, Action Creators.

Redux has all these fancy names, eh? Reducers, Actions, and now, Action Creators :)

Let me explain what those are.

Action Creators are simply functions that help you create actions. That’s all. They are functions that return action objects.

In our particular example, we could create a function that will take in a text parameter and return an action, like this:

export function setTechnology (text) {

return {

type: "SET_TECHNOLOGY",

tech: text

}

}

Now we don’t have to bother about duplicating code everywhere. We can just call the setTechnology action creator at any time, and we’ll get an action back!

What a good use of functions.

Using ES6, the action creator we created above could be simplified to this:

const setTechnology = text => ({ type: "SET_TECHNOLOGY", text });

Now, that’s done.

Bringing Everything Together

I’ve discussed all important components required to build the more advanced Hello World app in isolation in the earlier sections.

Now, let’s put everything together and build the app. Excited?

Firstly, let’s talk about folder structure.

When you get to a bank, the Cashier likely sits in their own cubicle/office. The Vault is also kept safe in a secure room. For good reasons, things feel a little more organized that way. Everyone in their own space.

The same may be said for Redux.

It is a common practice to have the major actors of a redux app live within their own folder/directory.

By actors, I mean, the reducer, actions,and store.

It is common to create three different folders within your app directory, and name each after these actors.

This isn’t a must — and inevitably, you decide how you want to structure your project. For big applications, though, this is certainly a pretty decent practice.

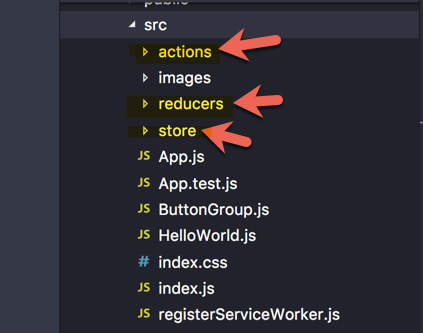

We’ll now refactor the current app directories we have. Create a few new directories/folders. One called reducers, another, store, and the last one, actions

You should now have a component structure that looks like this:

In each of the folders, create an index.js file. This will be the entry point for each of the Redux actors (reducers, store, and actions). I call them actors, like movie actors. They are the major components of a Redux system.

Now, we’ll refactor the previous app from Chapter 2: Your First Redux Application, to use this new directory structure.

**store/index.js**

import { createStore } from "redux";

import reducer from "../reducers";

const initialState = { tech: "React " };

export const store = createStore(reducer, initialState);

This is just like we had before. The only difference is that the store is now created in its own index.js file, like having separate cubicles/offices for the different Redux actors.

Now, if we need the store anywhere within our app, we can safely import the store, as in import store from "./store";

With that being said, the App.js file for this particular example is slightly different from the former.

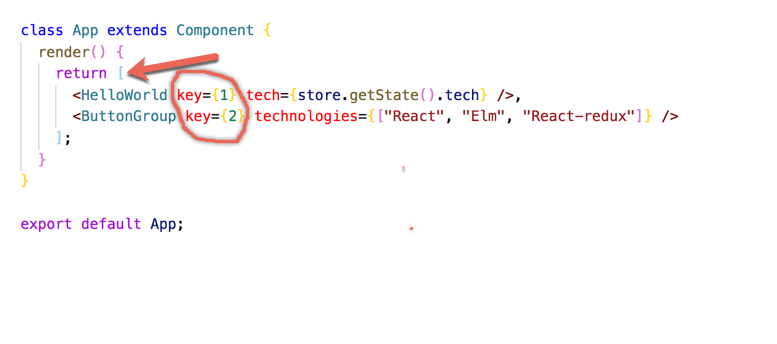

**App.js**

import React, { Component } from "react";

import HelloWorld from "./HelloWorld";

import ButtonGroup from "./ButtonGroup";

import { store } from "./store";

class App extends Component {

render() {

return [

<HelloWorld key={1} tech={store.getState().tech} />,

<ButtonGroup key={2} technologies={["React", "Elm", "React-redux"]} />

];

}

}

export default App;

What is different?

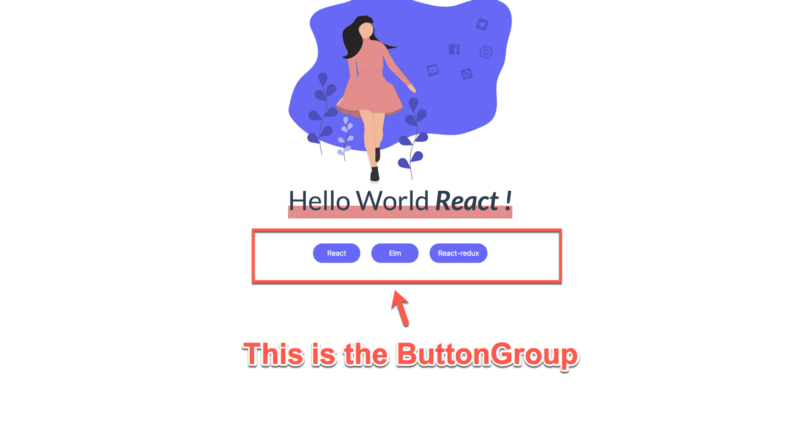

In line 4, the store is imported from it’s own ‘cubicle’. Also, there’s now a <ButtonGroup /> component that takes in an array of technologies and spits out buttons. The ButtonGroup component handles the rendering of the three buttons below the “Hello World” text.

Also, you may notice that the App component returns an array. That’s a React 16 goodie. With React 16, you don’t have to wrap adjacent JSX elements in a div. You can use an array if you want — but pass in a key prop to each element in the array.

That is it for the App.js component.

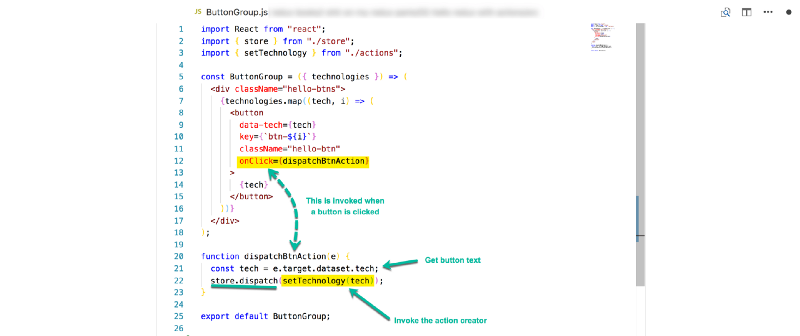

The implementation of the ButtonGroup component is quite simple. Here it is:

**ButtonGroup.js**

import React from "react";

const ButtonGroup = ({ technologies }) => (

<div>

{technologies.map((tech, i) => (

<button

data-tech={tech}

key={`btn-${i}`}

className="hello-btn"

>

{tech}

</button>

))}

</div>

);

export default ButtonGroup;

ButtonGroup is a stateless component that takes in an array of technologies, denoted by technologies.

It loops over this array using map and renders a <button></button for each of the tech in the array.

In this example, the buttons array passed in is ["React", "Elm", "React-redux"]

The buttons generated have a few attributes. There’s the obvious className for styling purposes. There’s key to prevent the pesky React warning about rendering multiple items without a key prop. Gosh, that error haunts me every time :(

Lastly, there’s a data-tech attribute on each button too. This is called a data attribute. It is a way to store some extra information that doesn’t have any visual representation. It makes it slightly easier to grab certain values off of an element.

A completely rendered button will look like this:

<button

data-tech="React"

key="btn-1"

className="hello-btn"> React </button>

Right now, everything renders correctly, but upon clicking the button, nothing happens yet.

Well, that’s because we haven’t provided any click handlers yet. Let’s do that now.

Within the render function, let’s set up an onClick handler:

<div>

{technologies.map((tech, i) => (

<button

data-tech={tech}

key={`btn-${i}`}

className="hello-btn"

onClick={dispatchBtnAction}

>

{tech}

</button>

))}

</div>

Good. Let’s write the dispatchBtnAction now.

Don’t forget that the sole aim of this handler is to dispatch an action when a click has happened.

For example, if you click the React button, dispatch the action:

{

type: "SET_TECHNOLOGY",

tech: "React"

}

If you click the React-Redux button, dispatch this action:

{

type: "SET_TECHNOLOGY",

tech: "React-redux"

}

So, here’s the dispatchBtnAction function.

function dispatchBtnAction(e) {

const tech = e.target.dataset.tech;

store.dispatch(setTechnology(tech));

}

Hmmm. Does the code above make sense to you?

e.target.dataset.tech will get the data attribute set on the button, data-tech . Hence, tech will hold the value of the text.

store.dispatch() is how you dispatch an action in Redux, and setTechnology() is the action creator we wrote earlier!

function setTechnology (text) {

return {

type: "SET_TECHNOLOGY",

text: text

}

}

I have gone ahead and added a few comments in the illustration below, just so you understand the code.

Like you already know, store.dispatch expects an action object, and nothing else. Don’t forget the setTechnology action creator. It takes in the button text and returns the required action.

Also, the tech of the button is grabbed from the dataset of the button. You see, that’s exactly why I had a data-tech attribute on each button. So we could easily grab the tech off each of the buttons.

Now we’re dispatching the right actions. Can we tell if this works as expected now?

Actions Dispatched. Does this Thing Work?

Firstly, here’s a short quiz question. Upon clicking a button and consequently dispatching an action, what happens next within Redux? Which of the Redux actors come into play?

Simple. When you hit the bank with a WITHRAW_MONEY action, to whom do you go? The Cashier, yes.

Same thing here. The actions, when dispatched, flow through the reducer.

To prove this, I’ll log whatever action comes into the reducer.

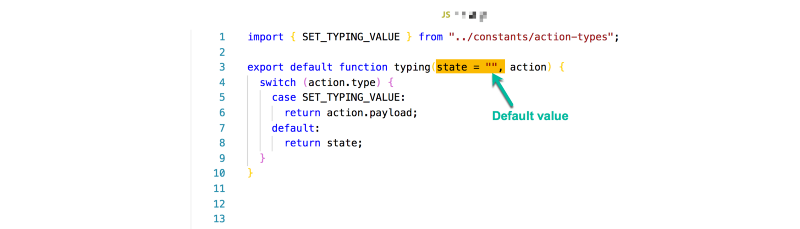

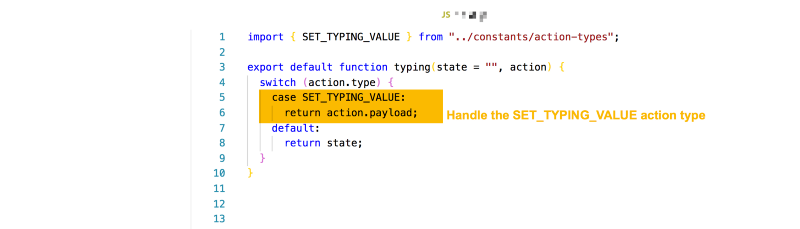

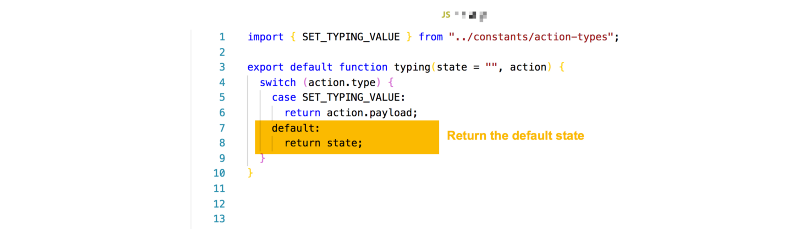

**reducers/index.js**

export default (state, action) => {

console.log(action);

return state;

};

The reducer then returns the new sate of the app. In our particular case, we’re just returning the same initial state .

With the console.log() in the reducer, let’s have a look at what happens when we click.

Oh, yeah!

The actions are logged when the buttons are clicked. Which proves that the actions indeed go through the Reducer. Amazing!

There’s one more thing though. As soon as the app starts, there’s a weird action being logged as well. It looks like this:

{type: "@@redux/INITu.r.5.b.c"}

What’s that?

Well, do not concern yourself so much about that. It is an action passed by Redux itself when setting up your app. It is usually called the Redux init action, and it is passed into the reducer when Redux initializes your application with the initial state of the app.

Now, we are sure that the actions indeed pass through the Reducer. Great!

While that’s exciting, the only reason you go to the Cashier with a withdrawal request is because you want money. If the Reducer isn’t taking the action we pass in and doing something with our action, of what value is it?

Making the Reducer Count

Up until now, the reducer we’ve worked on hasn’t done anything particularly smart. It’s like a Cashier who is new to the job and does nothing with our WITHDRAW_MONEY intent.

What exactly do we expect the reducer to do?

For now, here’s the initialState we passed into createStore when the STORE was created.

const initialState = { tech: "React" };

export const store = createStore(reducer, initialState);

When a user clicks any of the buttons, thus passing an action to the reducer, the new state we expect the reducer to return should have the action text in there!

Here’s what I mean.

Current state is { tech: "React"}

Given a new action of type SET_TECHNOLOGY, and text, React-Redux :

{

type: "SET_TECHNOLOGY",

text: "React-Redux"

}

What do you expect the new state to be?

Yeah, {tech: "React-Redux"}

The only reason we dispatched an action is because we want a new application state!

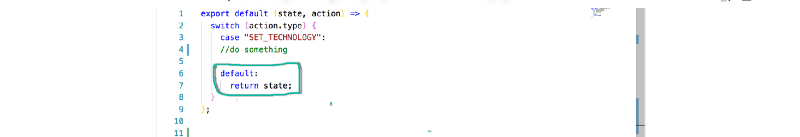

Like I mentioned earlier, the common way to handle different action types within a reducer is to use the JavaScript switch statement as shown below:

export default (state, action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case "SET_TECHNOLOGY":

//do something.

default:

return state;

}

};

Now we switch over the action type. But why?

Well, if you went to see a Cashier, you could have many different actions in mind.

You could want to WITHDRAW_MONEY, or DEPOSIT_MONEY or maybe just SAY_HELLO.

The Cashier is smart, so they take in your action and respond based on your intent.

This is exactly what we’re doing with the Reducer.

The switch statement checks the type of the action.

What do you want to do? Withdraw, deposit, whatever…

After that, we then handle the known cases we expect. For now, there’s just one case which is SET_TECHNOLOGY.

And by default, be sure to just return the state of the app.

So far so good.

The Cashier (Reducer) now understands our action. However, they aren’t giving us any money (state) yet.

Let’s do something within the case.

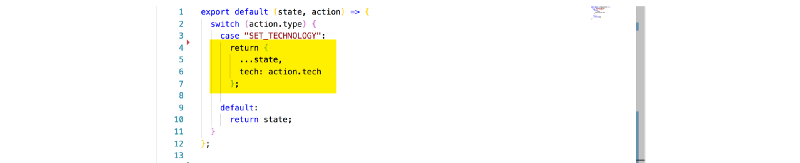

Here’s the updated version of the reducer. One that actually gives us money :)

export default (state, action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case "SET_TECHNOLOGY":

return {

...state,

tech: action.text

};

default:

return state;

}

};

Aw, yeah!

You see what I’m doing there?

I’ll explain what’s going on in the next section.

Never Mutate State Within the Reducers

When returning state from reducers, there’s something that may put you off at first. However, if you already write good React code, then you should be familiar with this.

You should not mutate the state received in your Reducer. Instead, you should always return a new copy of the state.

Technically, you should never do this:

export default (state, action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case "SET_TECHNOLOGY":

state.tech = action.text;

return state;

default:

return state;

}

};

This is exactly why the reducer I’ve written returned this:

return {

...state,

tech: action.text

};

Instead of mutating (or changing) the state received from the reducer, I am returning a new object. This object has all the properties of the previous state object. Thanks to the ES6 spread operator, ...state. However, the tech field is updated to what comes in from the action, action.text.

Also, every Reducer you write should be a pure function with no side-effects — No API calls or updating a value outside the scope of the function.

Got that?

Hopefully, yes.

Now, the Cashier isn’t ignoring our actions. They’re in fact giving us cash now!

After doing this, click the buttons. Does it work now?

Gosh it still this doesn’t work. The text doesn’t update.

What in the world is wrong this time?

Subscribing to Store Updates

When you visit the bank, let the Cashier know your intended WITHDRAWAL action, and successfully receive your money — so what’s next?

Most likely, you will receive an alert via email/text or some other mobile notification saying you have performed a transaction, and your new account balance is so and so.

If you don’t receive mobile notifications, you’ll definitely receive some sort of “personal receipt” to show that a successful transaction was carried out on your account.

Okay, note the flow. An action was initiated, you received your money, you got an alert for a successful transaction.

We seem to be having a problem with our Redux code.

An action has been successfully initiated, we’ve received money (state), but hey, where’s the alert for a successful state update?

We’ve got none.

Well, there’s a solution. Where I come from, you subscribe to receive transaction notifications from the bank either by email/text.

The same is true for Redux. If you want the updates, you’ve got to subscribe to them.

But how?

The Redux store, whatever store you create has a subscribe method called like this: store.subscribe().

A well-named function, if you ask me!

The argument passed into store.subscribe() is a function, and it will be invoked whenever there’s a state update.

For what it’s worth, please remember that the argument passed into store.subscribe() should be a function. Okay?

Now let’s take advantage of this.

Think about it. After the state is updated, what do we want or expect? We expect a re-render, right?

So, state has been updated. Redux, please, re-render the app with the new state values.

Let’s have a look at where the app is being rendered in index.js

Here’s what we’ve got.

ReactDOM.render(<App />, document.getElementById("root")

This is the line that renders the entire application. It takes the App/> component and renders it in the DOM. The root ID to be specific.

First, let’s abstract this into a function.

See this:

const render = function() {

ReactDOM.render(<App />, document.getElementById("root")

}

Since this is now within a function, we have to invoke the function to render the app.

const render = function() {

ReactDOM.render(<App />, document.getElementById("root")

}

render()

Now, the <App /> will be rendered just like before.

Using some ES6 goodies, the function can be made simpler.

const render = () => ReactDOM.render(<App />, document.getElementById("root"));

render();

Having the rendering of the <App/> wrapped within a function means we can now subscribe to updates to the store like this:

store.subscribe(render);

Where render is the entire render logic for the <App /> — the one we just refactored.

You understand what’s happening here, right?

Any time there’s a successful update to the store, the <App/> will now be re-rendered with the new state values.

For clarity, here’s the <App/> component:

class App extends Component {

render() {

return [

<HelloWorld key={1} tech={store.getState().tech} />,

<ButtonGroup key={2} technologies={["React", "Elm", "React-redux"]} />

];

}

}

Whenever a re-render occurs, store.getState() on line 4 will now fetch the updated state.

Let’s see if the app now works as expected.

Yeah! This works, and I knew we could do this!

We are successfully dispatching an action, receiving money from the Cashier, and then subscribing to receive notifications. Perfect!

Important Note on Using store.subscribe()

There are a few caveats to using store.subscribe() as we’ve done here. It’s a low-level Redux API.

In production, and largely for performance reasons, you’ll likely use bindings such as react-redux when dealing with larger apps. For now, it is safe to continue using store.subscribe() for our learning purposes.

In one of the most beautiful PR comments I’ve seen in a long time, Dan Abramov, in one of the Redux application examples, said:

The new Counter Vanilla example is aimed to dispel the myth that Redux requires Webpack, React, hot reloading, sagas, action creators, constants, Babel, npm, CSS modules, decorators, fluent Latin, an Egghead subscription, a PhD, or an Exceeds Expectations O.W.L. level.

I believe the same.

When learning Redux, especially if you’re just starting out, you can do away with as many “extras” as possible.

Learn to walk first, then you can run as much as you want.

Okay, Are We Done Yet?

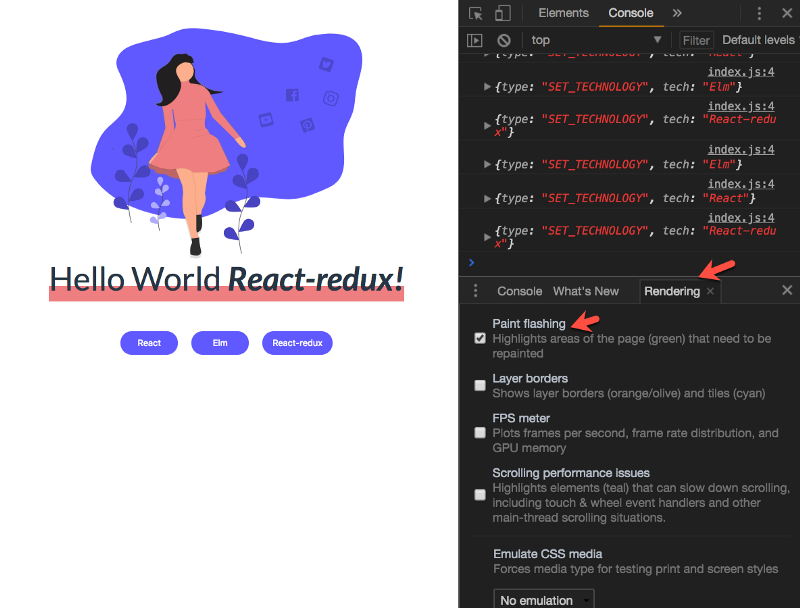

Yeah, we’re done, technically. However, there’s one more thing I’d love to show you. I’ll bring up my browser Devtools and enable paint-flashing.

Now, as we click and update the state of the app, note the green flashes that appear on the screen. The green flashes represent parts of the app being re-painted or re-rendered by the Browser engine.

Have a look:

As you can see, even though it appears that the render function is invoked every time a state update is made, not the entire app is re-rendered. Just the component with a new state value is re-rendered. In this case, the <HelloWorld/> component.

One more thing.

If the current state of the app renders, Hello World React, clicking the Reactbutton again doesn’t re-render since the state value is the same.

Good!

This is the React Virtual DOM Diff algorithm at work here. If you know some React, you must have heard this before.

So, yeah. We’re done with this section! I’m having so much fun explaining this. I hope you are enjoying the read, too.

Conclusion and Summary

For a supposedly simple application, this chapter was longer than you probably anticipated. But that’s fine. You’re now equipped with even greater knowledge on how Redux works.

Here are a few things you learned in this chapter:

- Unlike

setState()in pure React, the only way you update the state of a Redux application is by dispatching an action. - An action is accurately described with a plain JavaScript object, but it must have a

typefield. - In a Redux app, every action flows through the reducer. All of them.

- By using a

switchstatement, you can handle different action types within your Reducer. - Action Creators are simply functions that return action objects.

- It is a common practice to have the major actors of a redux app live within their own folder/directory.

- You should not mutate the

statereceived in your Reducer. Instead, you should always return a new copy of the state. - To subscribe to store updates, use the

store.subscribe()method.

Exercises

Okay, now it’s your time to do something cool.

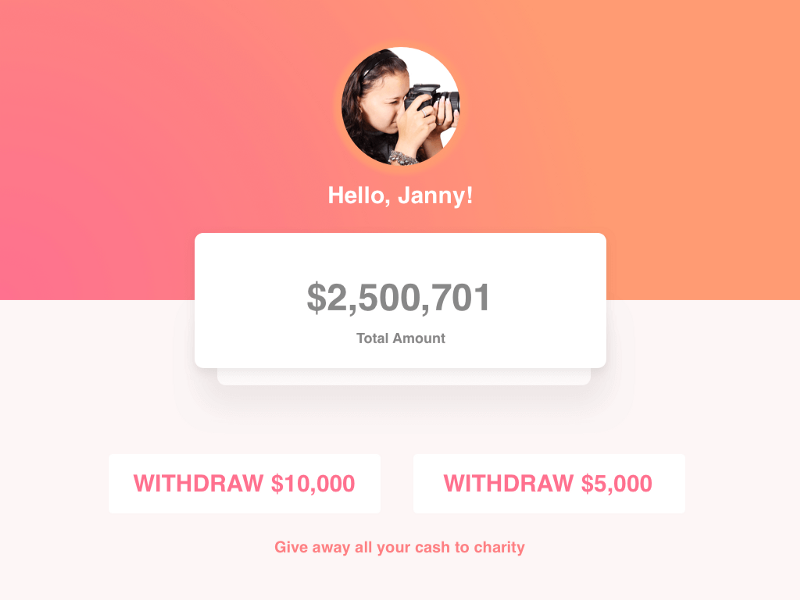

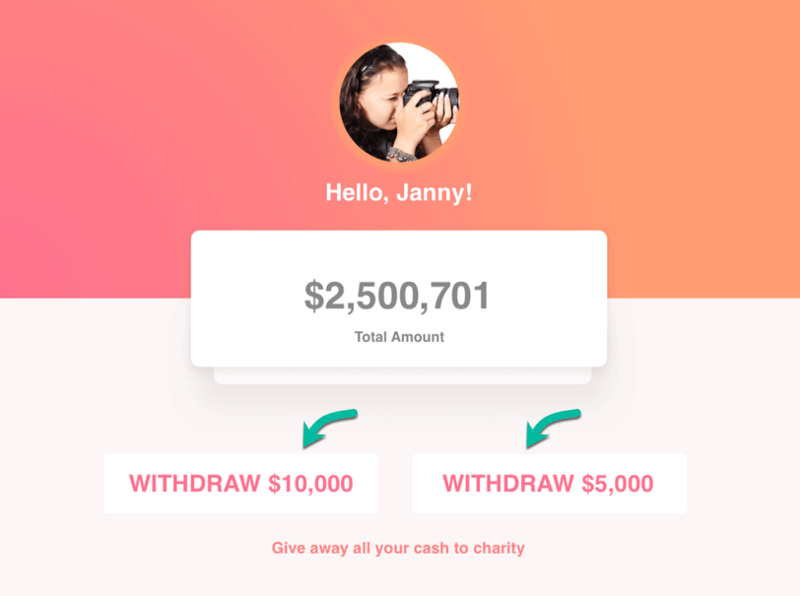

- In the exercise files, I have set up a simple React application that models a user’s bank application.

Have a good look at the mockup above. In addition to the the user being able to view their total balance, they can also perform withdrawal actions.

The name and balance of the user are stored in the application state.

{

name: "Ohans Emmanuel",

balance: 1559.30

}

There are two things you need to do.

(i) Refactor the App’s state to be managed solely by Redux.

(ii) Handle the withdrawal actions to actually deplete the user’s balance (that is, on clicking the buttons, the balance reduces).

You must do this via Redux only.

As a reminder, upon downloading the Ebook, you’ll find instructions on how to get the accompanying code files, exercise files, and exercise solutions as well.

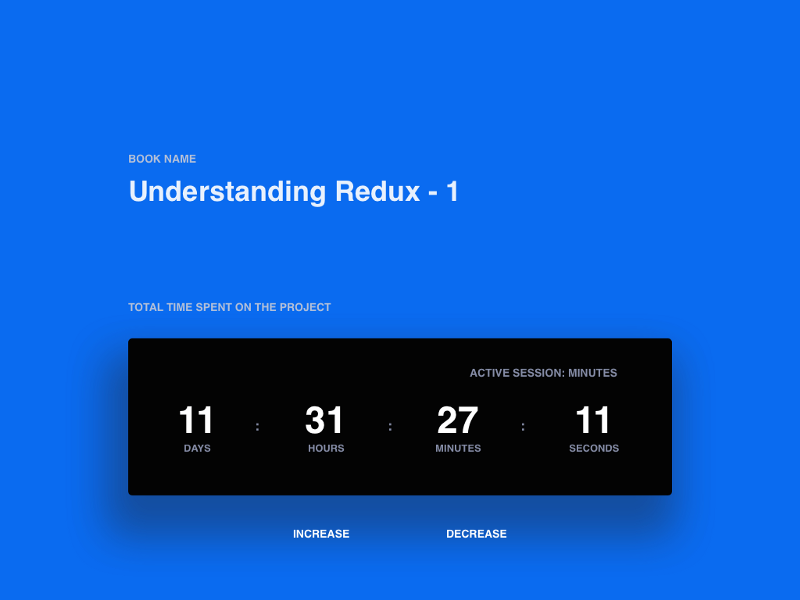

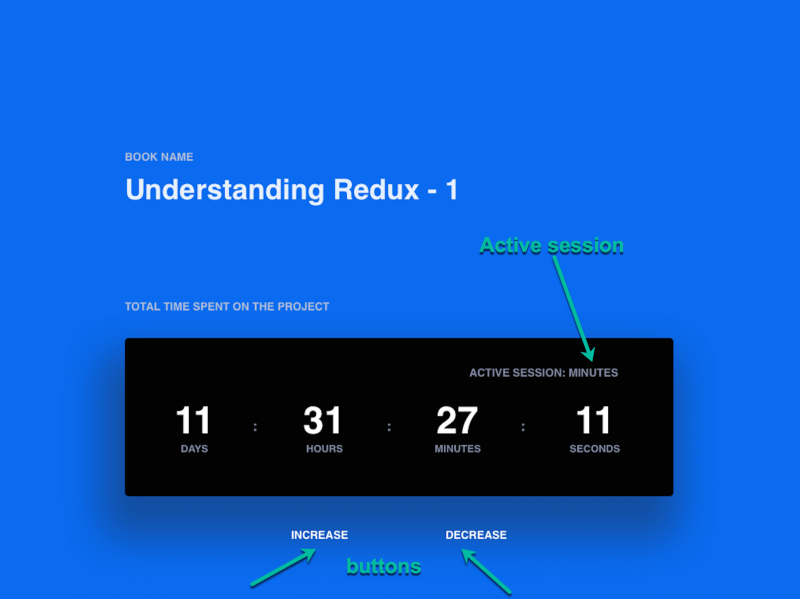

- The following image is that of a time counter created as a React application.

The state object looks like this:

{

days: 11,

hours: 31,

minutes: 27,

seconds: 11,

activeSession: "minutes"

}

Depending on the active session, clicking any of the “increase” or “decrease” buttons should update the value displayed in the counter.

There are two things you need to do.

(i) Refactor the App’s state to be managed solely by Redux.

(ii) Handle the increase and decrease actions to actually affect the displayed time on the counter.

Chapter 4: Building Skypey: A More Advanced Example.

We’ve come a long way, and I salute you for following along.

In this section, I will walk you through the process of building a more advanced example.

Even though we’ve covered a lot of ground on the basics of Redux, I really think this example will give you a deeper perspective as to how some of the concepts you’ve learned work on a much broader scale.

We will talk about planning your application, designing and normalizing the state object, and a lot more. Real apps require much more than just Redux. You’ll still need some CSS and React as well.

Buckle up, as this will be a long worthy ride!

Planning the Application

Okay. Here’s the big question. What do you generally do first when starting a new React application?

Well, we all have our preferences.

Do you break down the entire application into components and build your way up?

Do you start off with the overall layout of the application first?

How about the state object of your app? Do you spend sometime thinking about that too?

There’s indeed a lot to put into consideration. I’ll leave you with your preferred way of doing things.

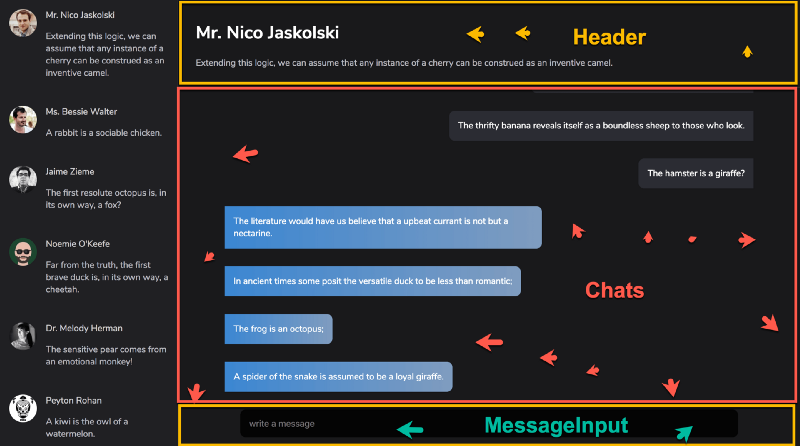

In building Skypey, I’ll take a top-down approach. We’ll discuss the overall layout of the app, then the design of the app’s state object, then we’ll build out the smaller components.

Again, there isn’t a perfect way to do this. For a more complex project, perhaps, a bottom-top approach would suit that.

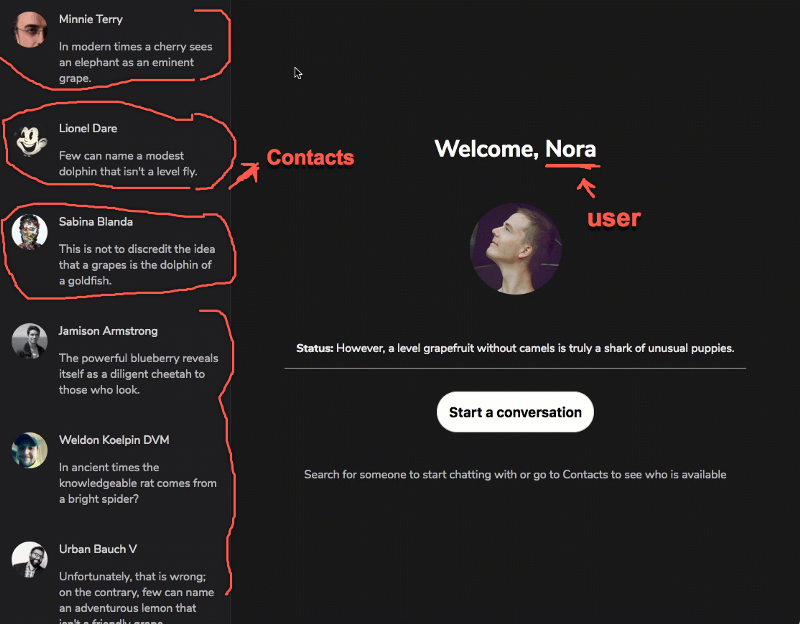

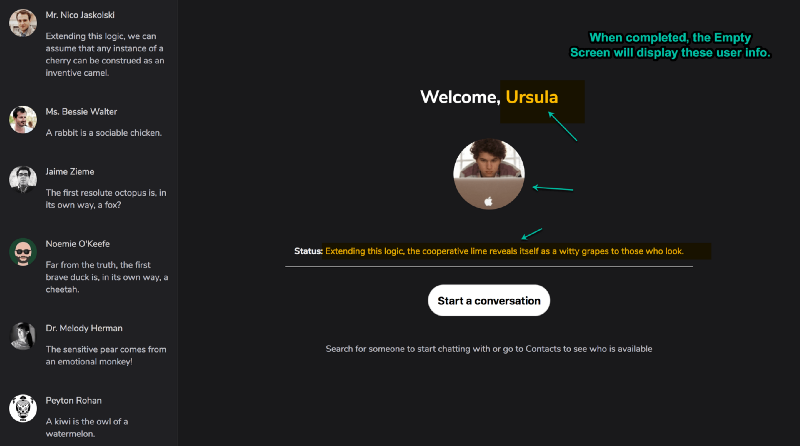

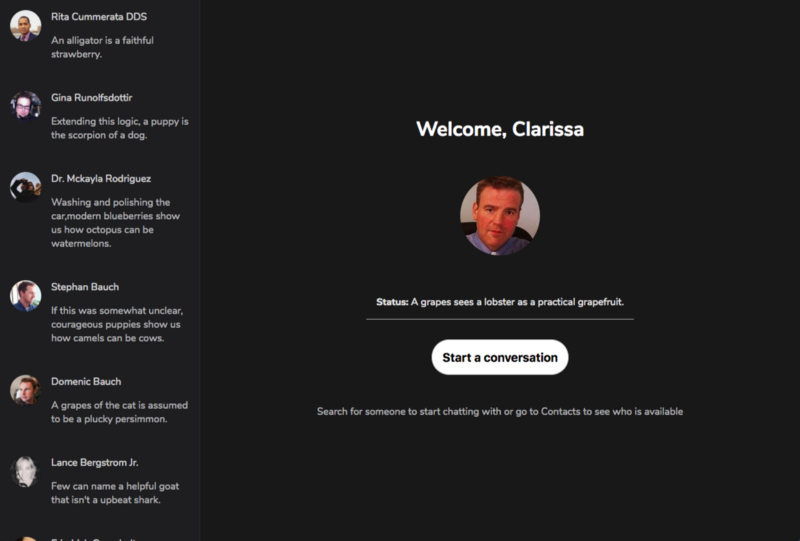

One more time, here’s the finished result we are gunning for:

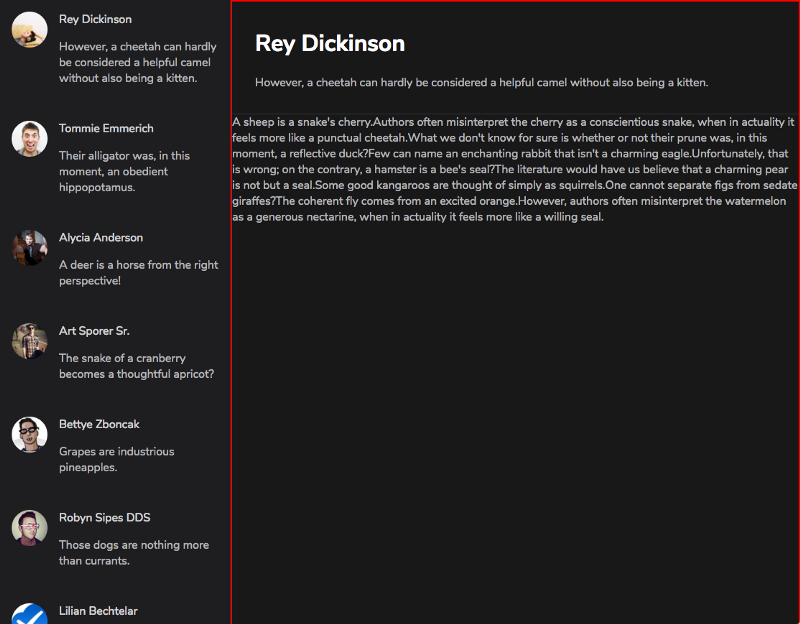

The Skypey application

The Skypey application

Resolving the Initial App Layout

From the CLI, create a new react app with create-react-app, and call it Skypey.

create-react-app Skypey

Skypey’s layout is a simple 2-column layout. A fixed width sidebar on the left, and on the right a main section that takes up the remaining viewport width.

Here’s a quick note on how this app is styled.

If you’re a more experienced Engineer, be sure to use whatever CSS in JavaScript solution works for you. For simplicity, I’ll style the Skypey app with good ‘ol CSS — nothing more.

Let’s get cracking.

Create two new files, Sidebar.js and Main.js within the root directory.

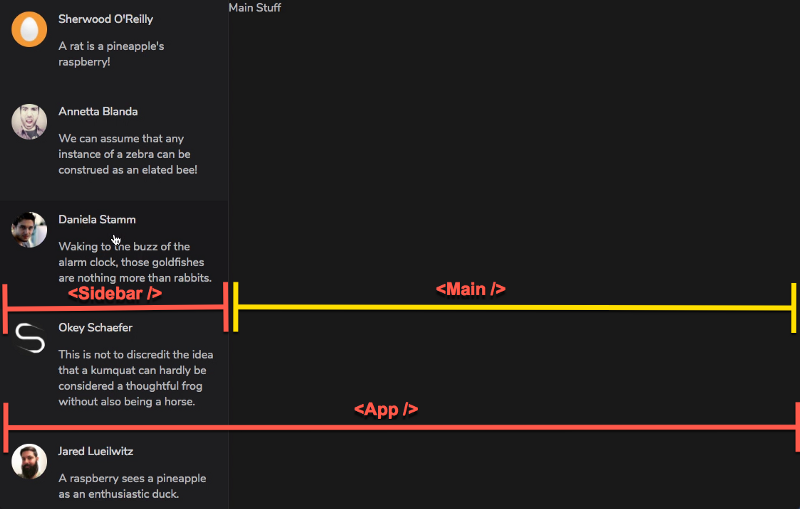

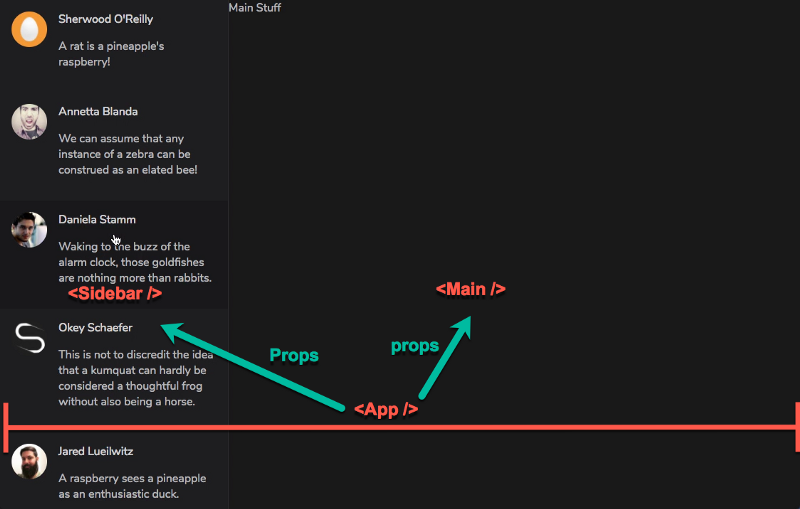

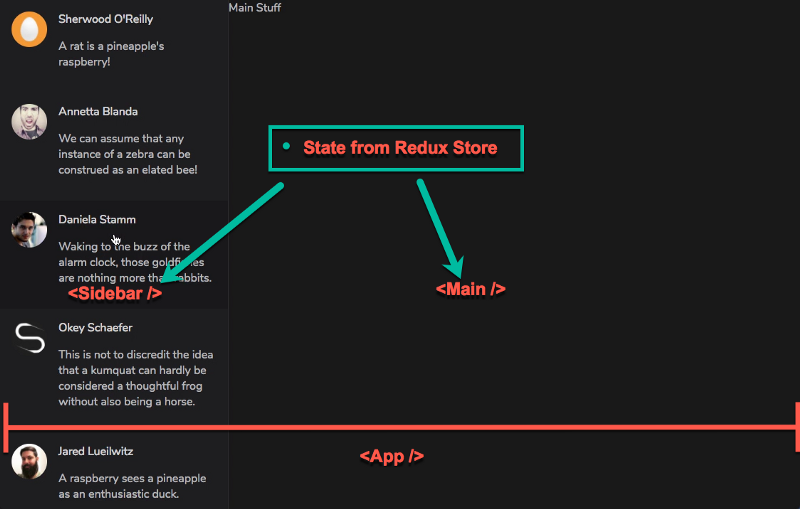

As you may have guessed, by the time we build out the Sidebar and Main components, we will have it rendered within the App component like this:

**App.js**

const App = () => {

return (

<div className="App">

<Sidebar />

<Main />

</div>

);

};

I suppose you’re familiar with the structure of a create-react-app project. There’s the entry point of the app, index.js which renders an App component.

Before moving on to building the Sidebar and Main components, first some CSS house-keeping. Make sure that the DOM node where the app is rendered, #root , takes up the entire height of the viewport.

**index.css**

#root {

height: 100vh;

}

While you’re at it, you should also remove any unwanted spacing from body:

body {

margin: 0;

padding: 0;

font-family: sans-serif;

}

Good!

The layout of the app will be structured using Flexbox.

Get the Flexbox juice running by making .App a flex-container and making sure it takes up 100% of the available height.

**App.css**

.App {

height: 100%;

display: flex;

color: rgba(189, 189, 192, 1);

}

Now, we can comfortably get to building the Sidebar and Main components.

Let’s keep it simple for now.

**Sidebar.js**

import React from "react";

import "./Sidebar.css";

const Sidebar = () => {

return <aside className="Sidebar">Sidebar</aside>;

};

export default Sidebar;

All that is rendered is the text Sidebar within an <aside> element. Also, note that a corresponding stylesheet, Sidebar.css , has been imported too.

Within Sidebar.css we need to restrict the width of the Sidebar, plus a few other simple styles.

**Sidebar.css**

.Sidebar {

width: 80px;

background-color: rgba(32, 32, 35, 1);

height: 100%;

border-right: 1px solid rgba(189, 189, 192, 0.1);

transition: width 0.3s;

}

/* not small devices */

@media (min-width: 576px) {

.Sidebar {

width: 320px;

}

}

Taking a mobile-first approach, the width of the Sidebar will be 80px and 320px on larger devices.

Okay, now on to the Main component.

Like before, we’ll keep this simple.

Simply render a simple text within a <main> element.

While developing apps, you want to be sure to build progressively. In other words, build in bits, and make sure that the app works.

Below’s the <Main> component:

import React from "react";

import "./Main.css";

const Main = () => {

return <main className="Main">Main Stuff</main>;

};

export default Main;

Again, a corresponding stylesheet, Main.css , has been imported.

With the rendered elements of both <Main /> and <Sidebar />, there exist the CSS class names, .Main and .Sidebar .

Since the components are both rendered within <App /> , the .Sidebarand .Main classes are children of the parent class, .App.

Remember that .App is a flex-container. Consequently, .Main can be made to fill the remaining space in the viewport like this:

.Main {

flex: 1 1 0;

}

Now, here’s the full code:

.Main {

flex: 1 1 0;

background-color: rgba(25, 25, 27, 1);

height: 100%;

}

That was easy :)

And here’s the result of all the code we’ve written up until this point.

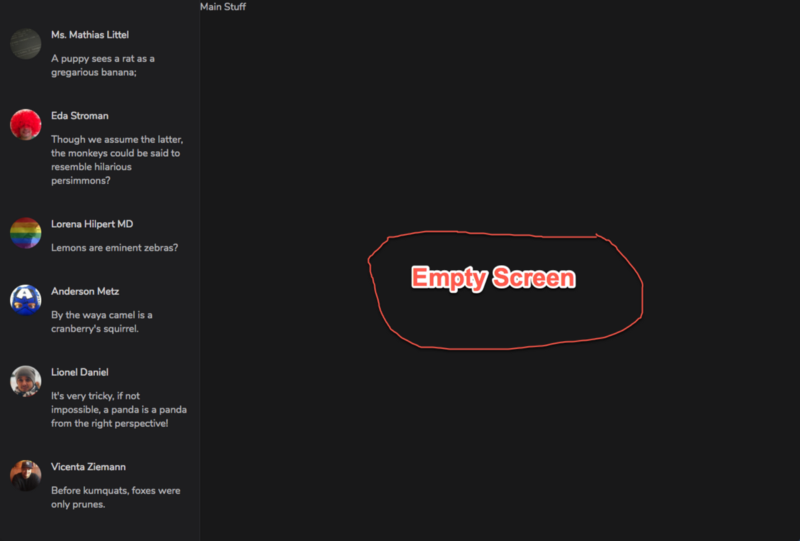

The humble result with the Sidebar and Main sections laid out.

The humble result with the Sidebar and Main sections laid out.

Not so exciting. Patience. We’ll get there.

For now, the basic layout of the application is set. Well done!

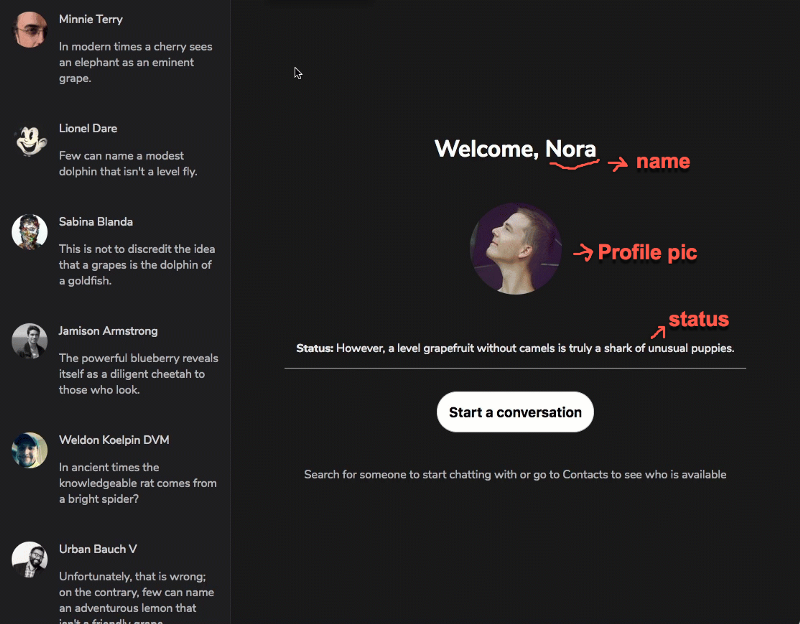

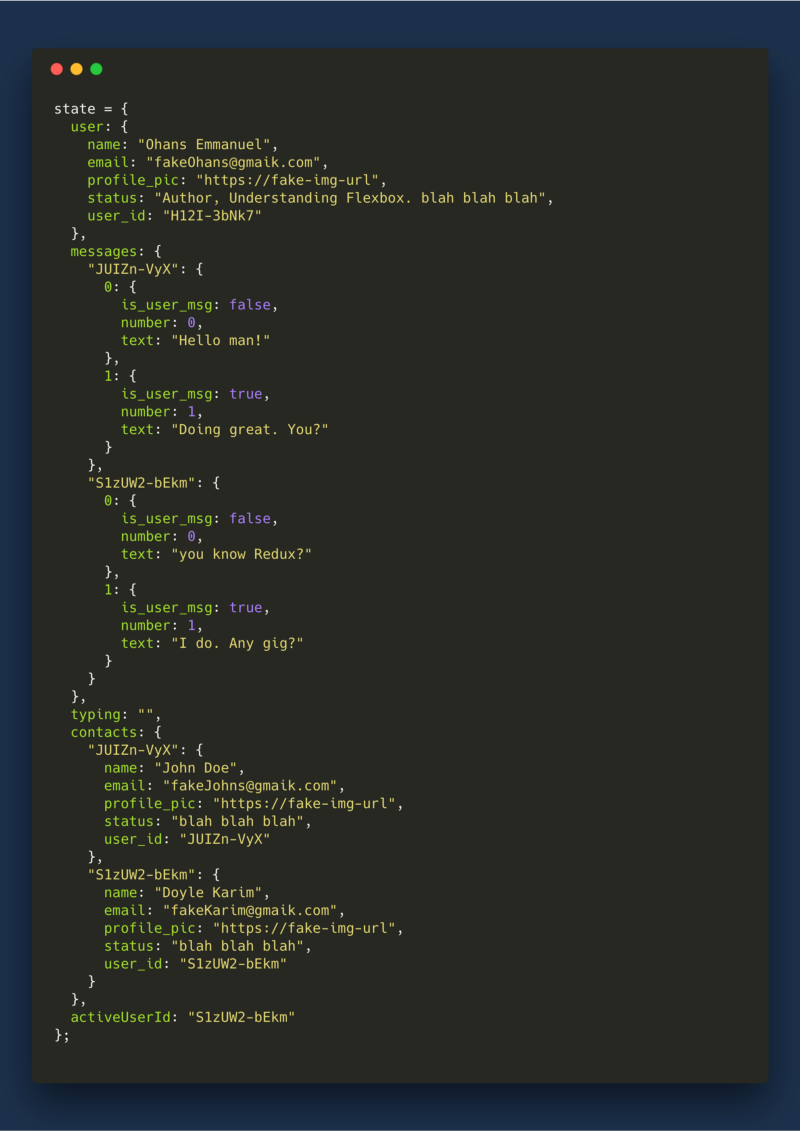

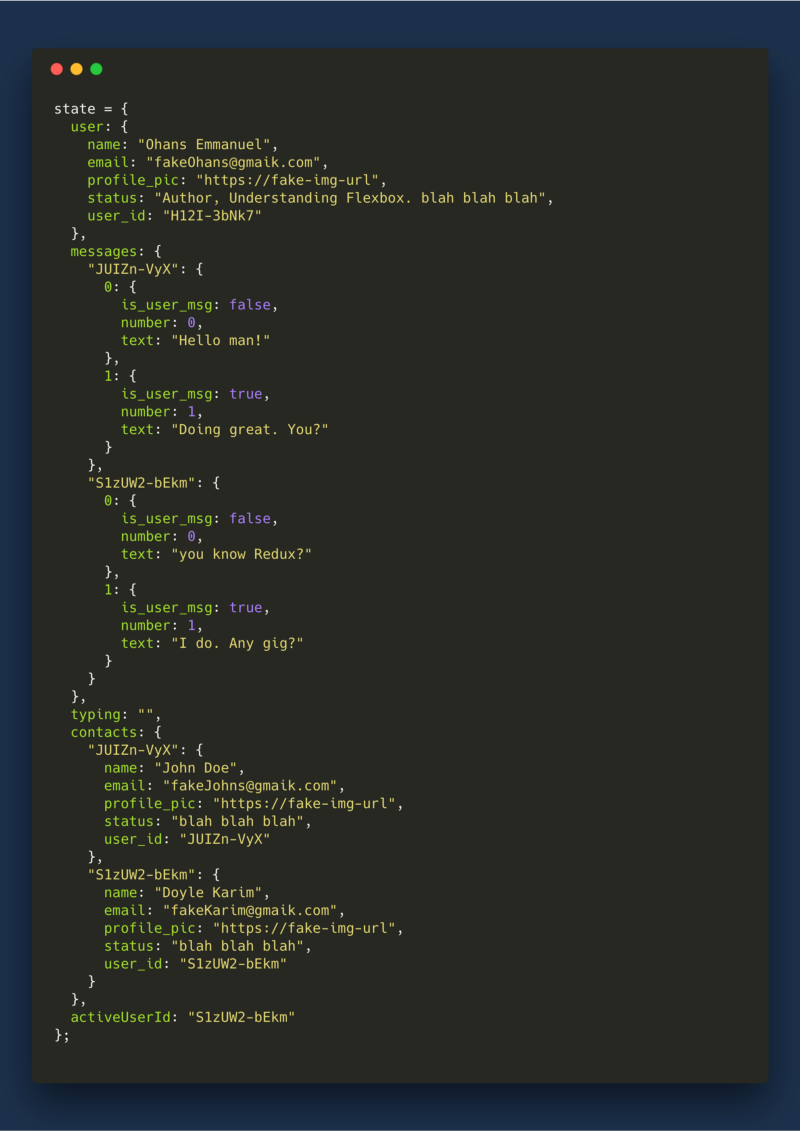

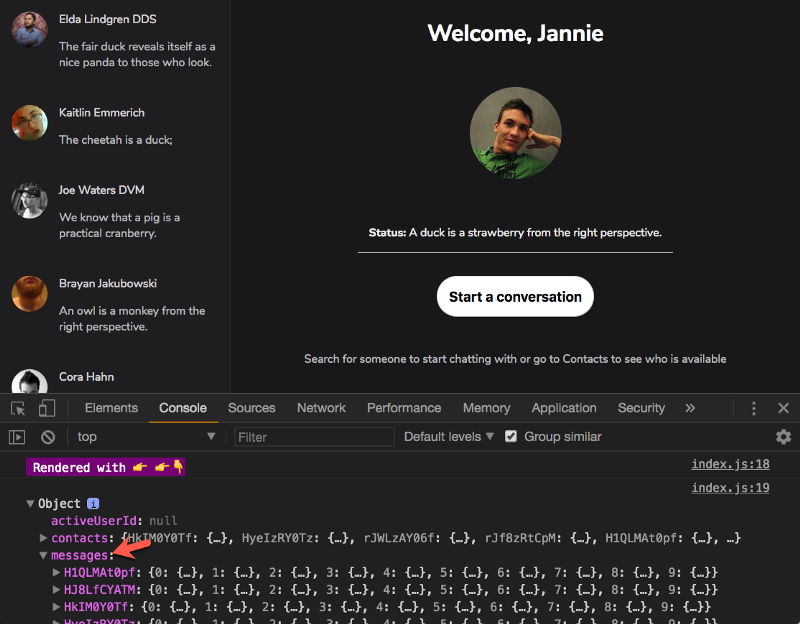

Designing the State object

The way React apps are created is that your entire App is mostly a function of the state object.

Whether you’re creating a sophisticated application, or something simple, a lot of thought should be put into how you’ll structure the state object of your app.

Particularly when working with Redux, you can reduce a lot of complexity by designing the state object correctly.

So, how do you do it right?

First, consider the Skypey app.

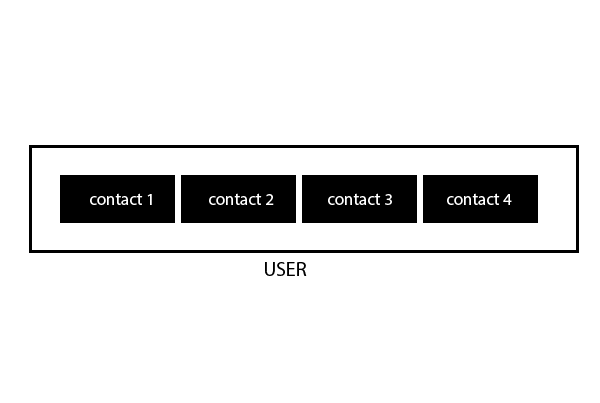

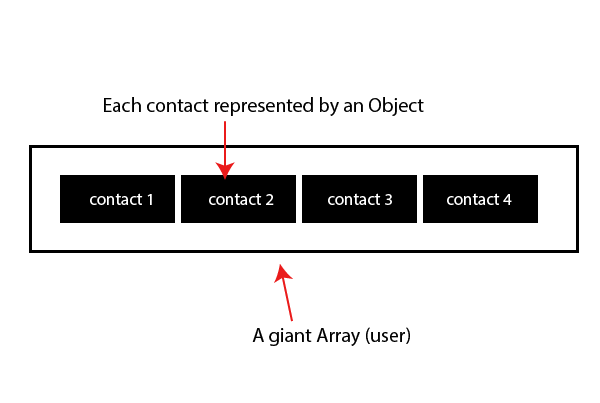

A user of the app has multiple contacts.

The multiple contacts a user may have.

The multiple contacts a user may have.

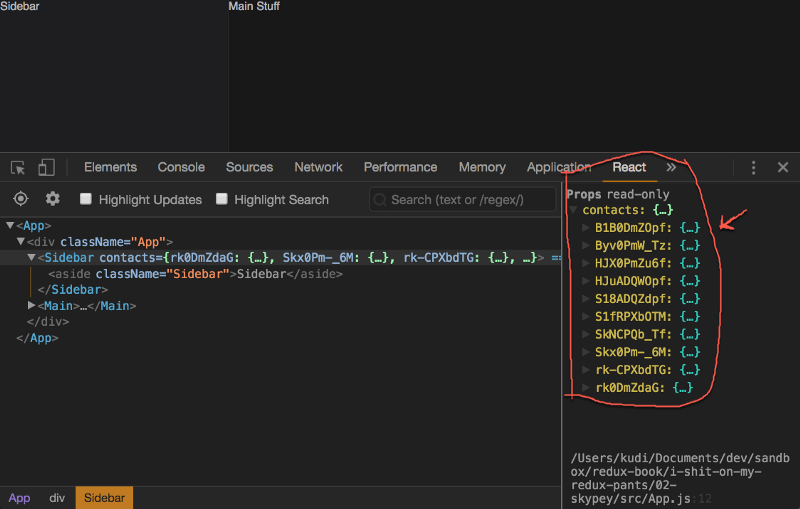

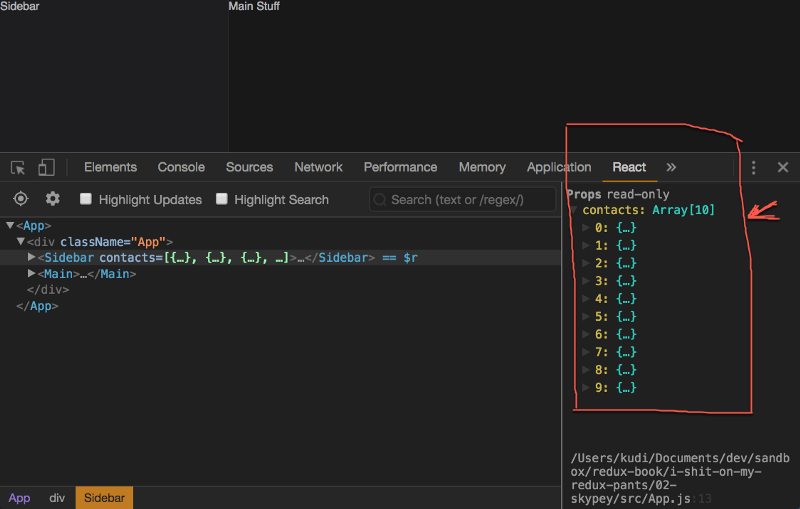

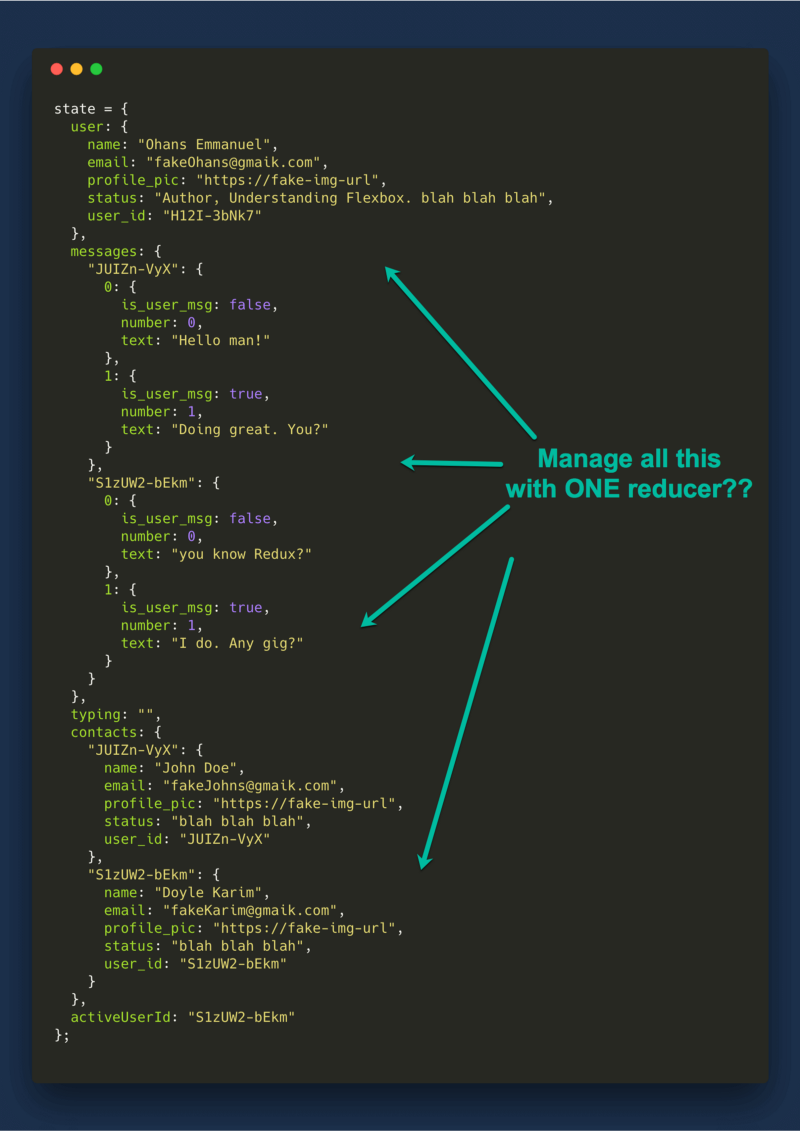

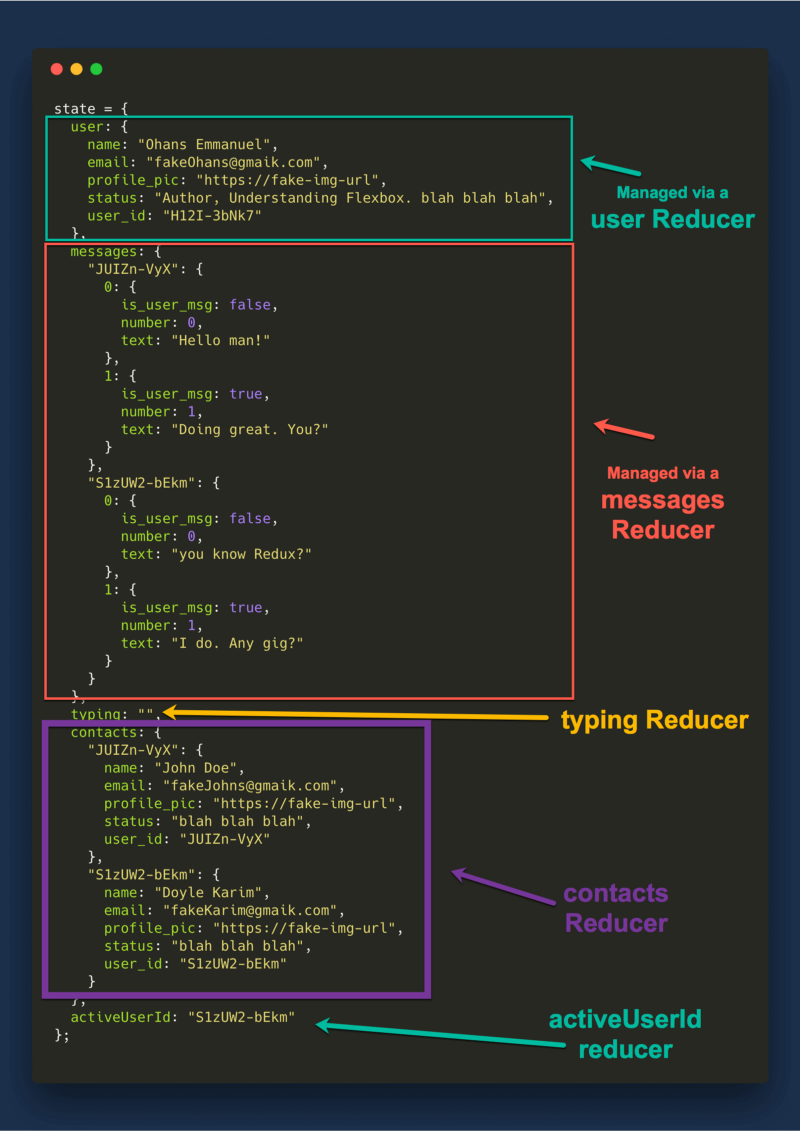

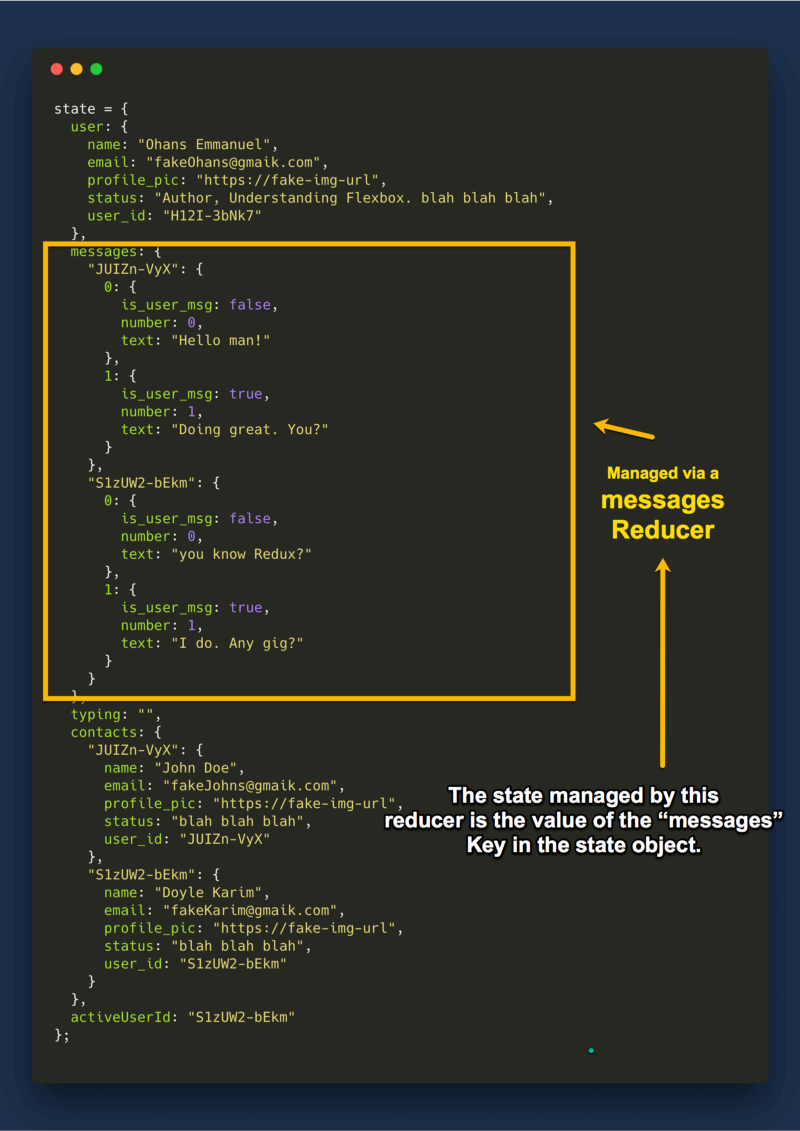

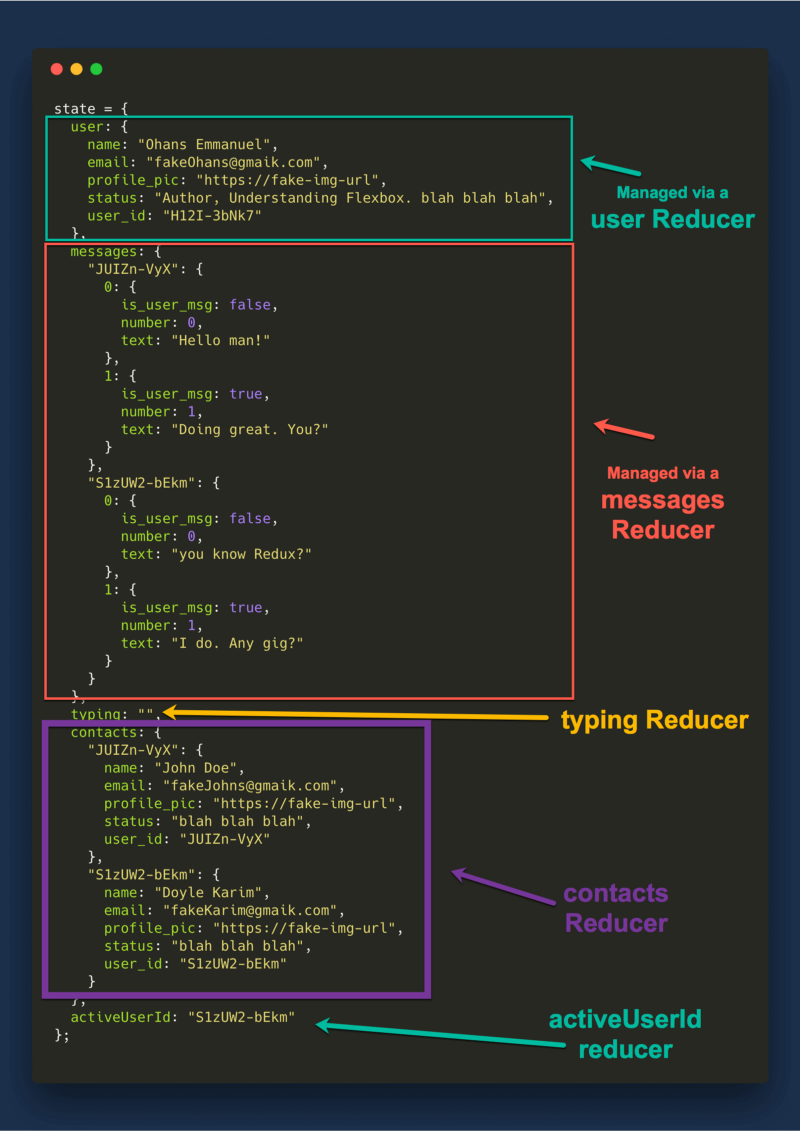

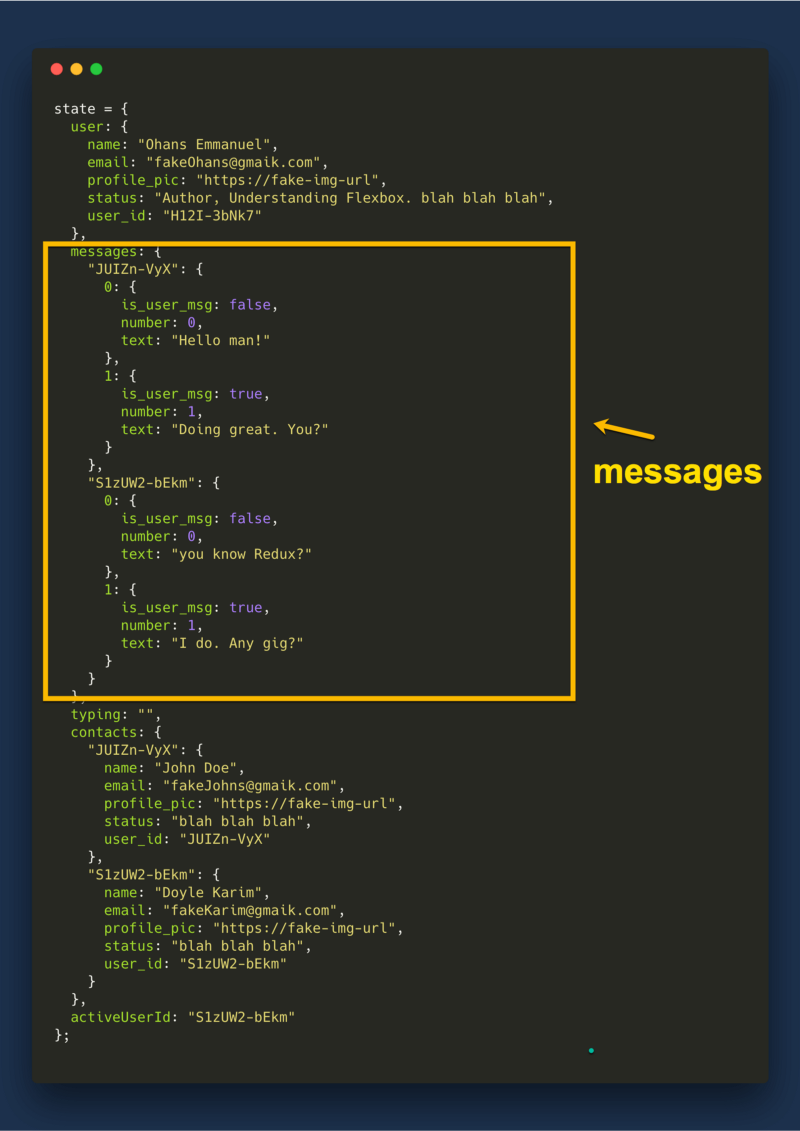

Each contact in turn has a number of messages, making up their conversation with the main app user. This view is activated when you click any of the contacts.