In this article, I'll share my experience and the lessons I learned attending (and winning) my first hackathon (spoiler alert: you're not actually hacking anything...😁).

One of the reasons I love the world of design so much is that its constant evolution requires you to maintain a growth mindset. You always have to be eager to upskill or explore a new craft. And as someone who finds great fulfillment in a meaningful challenge, this works especially well for me.

And so I put it to the test: I humbly signed up for my first hackathon, only moderately aware of what such an event entails. I was even less certain of what valuable contributions I could bring to the table as a (very) Junior UX Designer. Challenge accepted.

The first hurdle was finding a hackathon to participate in in the first place. I was overwhelmed by the number of choices out there, and found that a majority of hackathons were for students-only. This left university graduates and current bootcamp students like myself in a gray area.

Nonetheless, I set my sights on the more inclusive and social cause-driven events I could find, and reached out to the organizers to confirm my eligibility after applying.

A few exchanges later, I was accepted into DubHacks, the largest 24-hour hackathon in the Pacific Northwest.

After putting my imposter syndrome aside, forming a team, and getting through an exhaustive 24 hours, my team’s project went on to win the Best Use for Social Good category. Here are some things I learned from the experience.

Why Every Hackathon Team Needs a Designer

I’m pleased to report that what you’ve heard many times over in design school or in tutorials is true: not everyone thinks like a designer.

My team consisted of brilliant developers who were able to quickly deduce how to use their knowledge to build a software tool, but were less well-versed on how to build a viable product.

A good designer knows that a product is not merely the sum of its parts, but is a coherent and cohesive experience — this is exactly the unique perspective a designer brings to the table at a hackathon.

As a designer on the team, it’s your job to look beyond what you're building on a mechanical level, and constantly direct the team towards the greater, more human level of what you’re creating.

Yes, the framework and the tech stack are vital, but what good is the greatest technology if it’s unusable (or unclear) to the people who need it most?

Whenever our product’s positioning started to feel too broad or unfocused, I’d do my best to reign it in, reminding the team who we were building for, what our primary use cases were, and what problem we were trying to solve.

What the Designer Does on a Hackathon Team

If you’re a designer who wants to participate in a hackathon and you aren’t sure what deliverables or actionable steps you should take throughout the process (like I was), here’s an overview of what my involvement looked like.

Landscape Analysis

This is a crucial aspect of your hackathon project that shouldn’t be overlooked. Your project will not only be judged by its execution, but also its viability — what problem is it solving? Which users does it help? How do you know this?

This is a great chance to tap into your Design Thinking process and get to the root of the problem you’re building a solution for.

For me, this involved doing extensive research into the issues surrounding our chosen problem area, as well as the existing tools in the market that aim to solve similar (or different) issues.

I also snuck in some user research by reaching out to relevant acquaintances for short, informal user interviews to gain a better idea of their experience and pain points in this area.

This was an invaluable step in our process. When it came time to present our project, we not only had a minimum viable product to showcase, but the research to validate the need for our product in the first place.

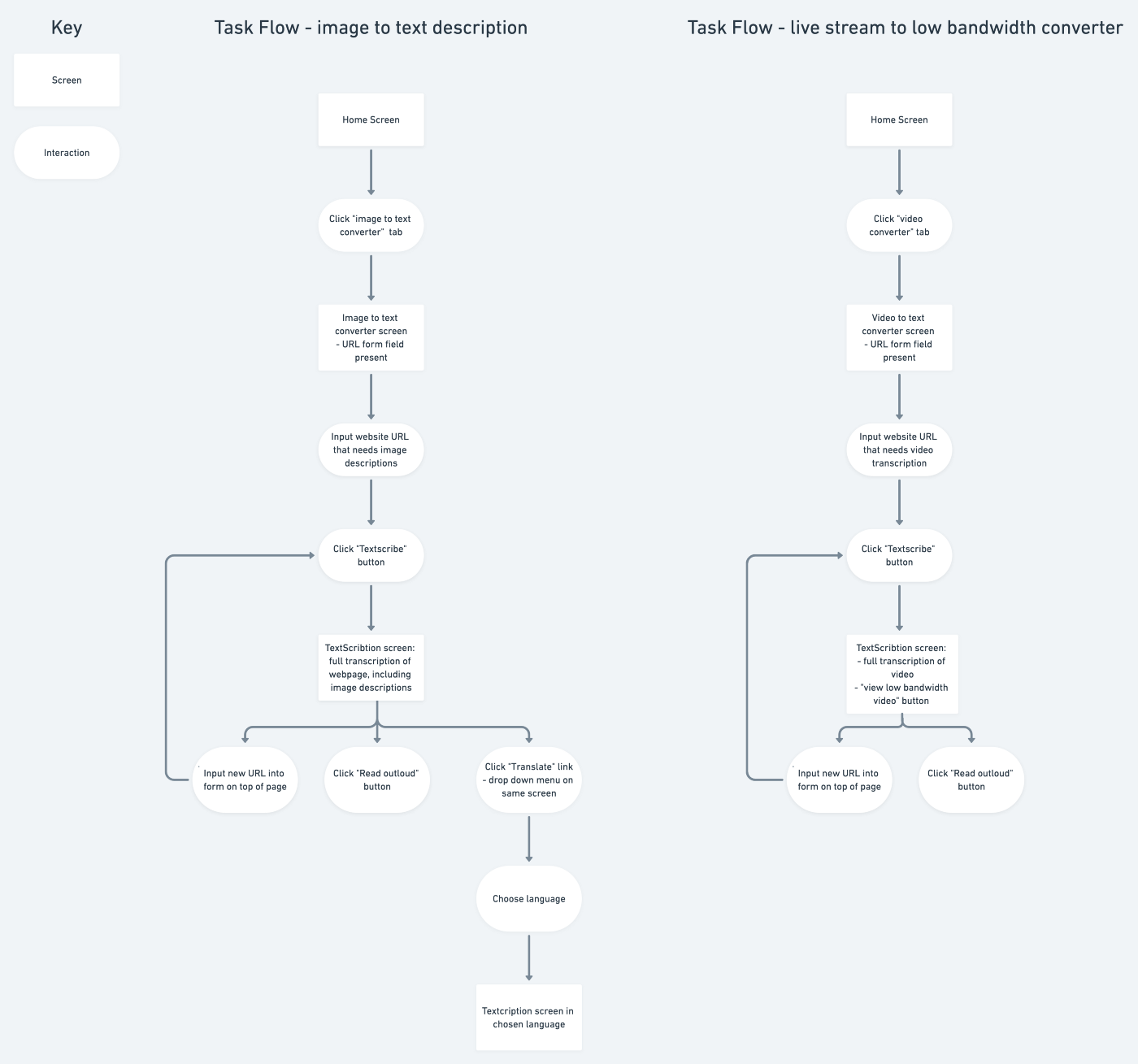

Task Flows and Sketches

Due to the rushed and scrappy nature of hackathons, your finished project will not be fully fleshed out. This means it’s important to at least include the most essential features.

Creating your product’s primary task flow(s) helps the developers jump right into working on the most important functions first. This is especially helpful if your team ends up not being able to complete the development of your other task flows by the submission deadline.

Rough sketches of what the interface will look like help developers contextualize what they’re building from the start and provide important constraints, however loose.

These were the first deliverables I sent to my team when the hackathon began. I explained to them the main task(s) we should aim to develop, and walked through my sketches of the interface, making note of the most important components on each screen (mainly our CTAs).

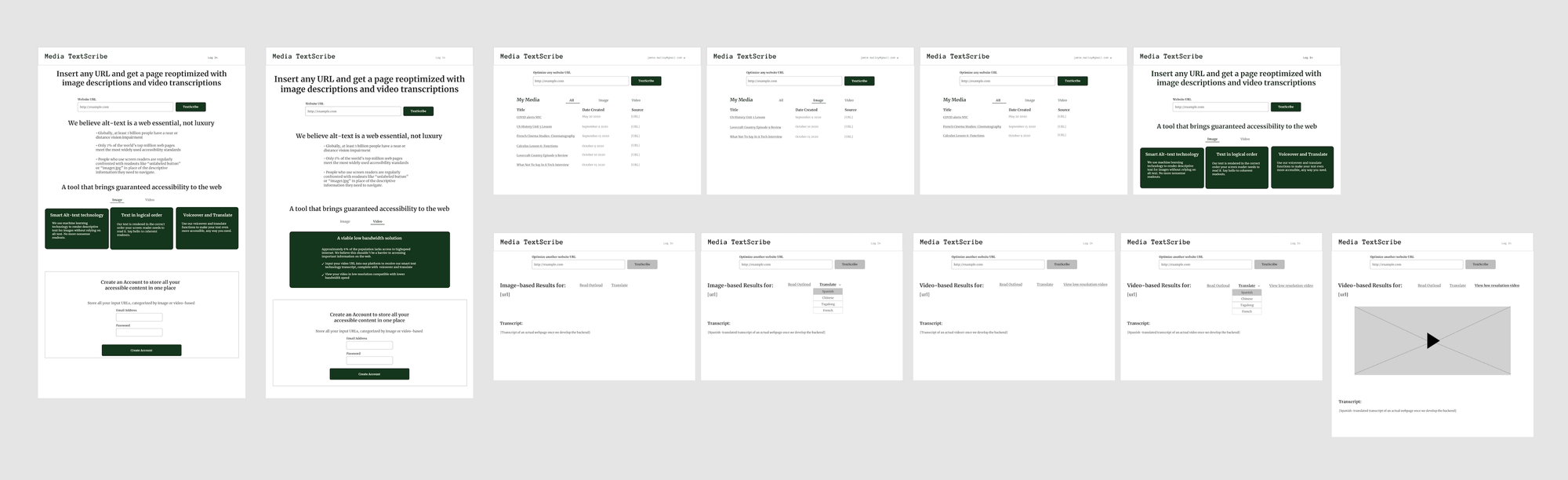

Wireframes and MockUps

Wireframes take your rough sketches one step further and give your developers even more important constraints to work with. Using tools like Figma or Zepplin to share your designs with your developers makes the best use of your time, as they can inspect and use the corresponding code.

Adding high fidelity mockups in your presentation helps showcase your work and make it feel more real/functional than your MVP, which will most likely look like your low-fidelity wireframes.

My team didn’t officially start coding the front-end of our product until I sent them low-fidelity wireframes. After I shared the designs for the main interfaces, I spent a lot of time designing multiple screens and high-fidelity wireframes that we never would have had time to develop.

Instead, I’d recommend focusing on the main interface(s) your devs will be building, and then flesh out a high-fidelity version for the purposes of your mockup and presentation.

To showcase the design in our presentation, I placed a PNG mockup of our product’s landing page in a device (using a Figma Community file template), as well as an additional short promo video I made using Rotato.

Project Management and Presentation

As a designer, you have a holistic perspective on what your team is trying to build beyond the code. Coupled with the landscape research you conducted, this lends perfectly to taking the lead on building your team’s final presentation.

Your presentation is the “big sell” of your project — without it, your product has no context, and can’t be judged by the panel. Your presentation doesn’t need to be immaculately designed in and of itself, but should include a few key points, such as:

- An introduction to your hack and team members

- The problem you’re trying to solve

- Your user base and business use cases, and how your product solves for these problems

- Tech stack and product features

- Long term impact of your product

- Difficulties and complications you encountered, and what you learned along the way

I built our presentation in Canva, which allows for easy collaboration and embedded media.

Designers have the unique advantage of not being pigeon-holed into one sole workflow during hackathons, which allows you to move your team along if/when they’re getting lost in code.

This establishes important time limits and constraints, and helps make sure you distribute your time and tasks efficiently.

Throughout the 24-hour event, I reminded my team of our upcoming deadlines: what time we should have our MVP finalized, when we would start practicing our presentation, and our submission deadline. I left sufficient buffer room for each in case anything went wrong or got delayed (which, in the world of hackathons, is a near guarantee).

Where Empathy Meets Strategy

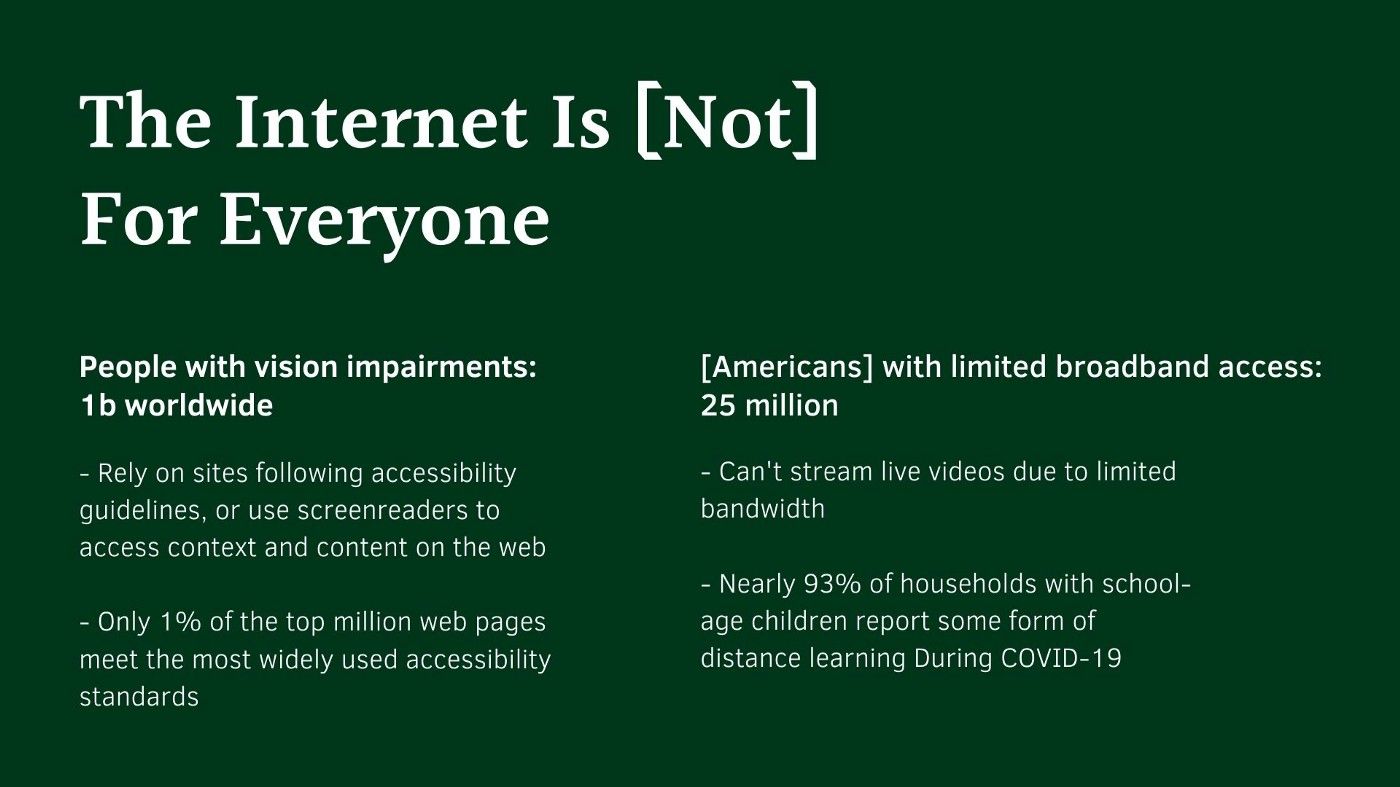

Our project idea was born out of my passion for making the web more accessible for people with disabilities and limited access to the internet.

I strongly believe design (and tech) is a tool with which we can dismantle exclusionary systems in favor for more inclusive ones. And this commitment to serving underrepresented groups fueled our work throughout the event.

I was lucky to be on a team with a member who already had some hackathon experience which allowed us to streamline our process. But looking back, there were other clear steps we took which contributed to our win in the Best Use for Social Good category.

Here’s my short list of tips to keep in mind to conquer your first (or any) hackathon experience as a designer:

1. Start Early

I don’t mean that you should begin any actual hacking earlier than the event start time, of course. But I do suggest getting to know your team, synthesizing some project ideas, and coming up with an action plan before the hackathon actually begins.

Our team hopped on a Google Doc one week before the hackathon to list out each of our core skills and propose 2 project ideas for us to later vote on.

Before the hackathon even started, we already had a good idea of who our team members were, what we were good at, and what we’d be building in the 24 hour timeframe.

2. Do your research

I can't overstate the importance of research in your process. It not only helps you reach your problem statement and validate the world's need for your project, but also serves as a reminder during the more daunting hours of the event what impact you’re hoping to make.

In moments of insecurity, I’d look back at the research I’d done in this problem space, remind myself of the quantifiable need for a solution, and use that as fuel to keep pushing.

3. Be Agile

I learned pretty quickly that, perhaps unsurprisingly, building a minimum viable product from scratch in a short amount of time gets messy. Not everything you set out to build in the beginning of the hackathon will make it into the final design, and that’s okay.

This is a great environment to be scrappy, fail fast, iterate, and streamline your workflow as much as possible.

4. Communicate clearly and frequently

Our team communicated mainly via Facebook Messenger, where the developers could quickly troubleshoot and bounce ideas off each other.

I used that communication channel to keep the team updated on what I was working on, make some UI notes, ask if anyone needed me for anything.

I also used it to remind the team of what I needed from them, be it some tech copy to put into our presentation or a reminder of the hour deadline we agreed to start reviewing our project by.

5. Be passionate

The cliche is not lost on me, either, but it’s true. Even your dream design job may come with some projects you’re not super excited about.

Hackathons, on the other hand, provide the unique opportunity to build something you exclusively excited about, under no obligation other than your own will.

Whether it's a social cause or a creative technology, finding a project you’re deeply passionate about will help guide, sustain, and validate your work from beginning to end.

TL;DR: Get out there and be great

I hope this guide serves both as a framework for the seasoned designer to help structure your workflow during a hackathon, and as inspiration for the young designer to participate in the crazy, chaotic, thrilling, and rewarding world of hackathons head-on.

Had I let my fear and intimidation get the best of me, I would have missed out on a tremendous learning opportunity. Beyond design deliverables, my first hackathon experience allowed me to practice my communication skills, work closely with developers and find a common language between us to help progress our work, and become comfortable working under tight timelines and constraints.

These are all skills that are invaluable to a designer on any level, but they're especially insightful for a junior in the field who may not yet have ample opportunities to learn by doing.

So I encourage any and every designer reading this to be brave and be great — I’ll be cheering you on.