By Tim Grossmann

Most jobs have repetitive tasks that you can automate, which frees up some of your valuable time. This makes automation a key skill to acquire.

A small group of skilled automation engineers and domain experts may be able to automate many of the most tedious tasks of entire teams.

In this article, we'll explore the basics of workflow automation using Python – a powerful and easy to learn programming language. We will use Python to write an easy and helpful little automation script that will clean up a given folder and put each file into its according folder.

Our goal won't be to write perfect code or create ideal architectures in the beginning.

We also won't build anything "illegal". Instead we'll look at how to create a script that automatically cleans up a given folder and all of its files.

Table of contents

- Areas of Automation and Where to Start

- Simple Automation

- Public API Automation

- API Reverse Engineering

- Ethical Considerations of Automation

- Creating a Directory Clean-Up Script

- A Complete Guide to Bot Creation and Automating Your Everyday Work

Areas of Automation and Where to Start

Let's start with defining what kind of automations there are.

The art of automation applies to most sectors. For starters, it helps with tasks like extracting email addresses from a bunch of documents so you can do an email blast. Or more complex approaches like optimizing workflows and processes inside of large corporations.

Of course, going from small personal scripts to large automation infrastructure that replaces actual people involves a process of learning and improving. So let's see where you can start your journey.

Simple Automations

Simple automations allow for a quick and straightforward entry point. This can cover small independent processes like project clean-ups and re-structuring of files inside of directories, or parts of a workflow like automatically resizing already saved files.

Public API Automations

Public API automations are the most common form of automation since we can access most functionality using HTTP requests to APIs nowadays. For example, if you want to automate the watering of your self-made smart garden at home.

To do that, you want to check the weather of the current day to see whether you need to water or if there is rain incoming.

API Reverse Engineering

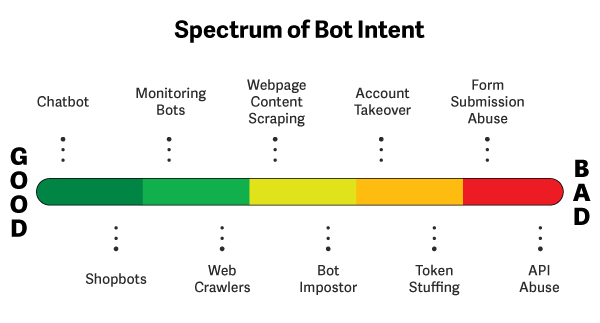

API reverse engineering-based automation is more common in actual bots and the "Bot Imposter" section of the chart in the "Ethical Considerations" section below.

By reverse-engineering an API, we understand the user flow of applications. One example could be the login into an online browser game.

By understanding the login and authentication process, we can duplicate that behaviour with our own script. Then we can create our own interface to work with the application even though they don't provide it themselves.

Whatever approach you're aiming at, always consider whether it's legal or not.

You don't want to get yourself into trouble, do you? ?

Ethical Considerations

Some guy on GitHub once contacted me and told me this:

“Likes and engagement are digital currency and you are devaluing them.”

This stuck with me and made me question the tool I've built for exactly that purpose.

The fact that these interactions and the engagement can be automated and “faked” more and more leads to a distorted and broken social media system.

People who produce valuable and good content are invisible to other users and advertisement companies if they don’t use bots and other engagement systems.

A friend of mine came up with the following association with Dante’s “Nine Circles of Hell” where with each step closer to becoming a social influencer you get less and less aware of how broken this whole system actually is.

I want to share this with you here since I think it's an extremely accurate representation of what I witnessed while actively working with Influencers with InstaPy.

Level 1: Limbo - If you don’t bot at all

Level 2: Flirtation - When you manually like and follow as many people as you can to get them to follow you back / like your posts

Level 3: Conspiracy - when you join a Telegram group to like and comment on 10 photos so the next 10 people will like and comment on your photo

Level 4: Infidelity - When you use a low-cost Virtual Assistant to like and follow on your behalf

Level 5: Lust - When you use a bot to give likes, and don’t receive any likes back in return (but you don’t pay for it - for example, a Chrome extension)

Level 6: Promiscuity - When you use a bot to Give 50+ likes to Get 50+ likes, but you don’t pay for it - for example, a Chrome extension

Level 7: Avarice or Extreme Greed - When you use a bot to Like / Follow / Comment on between 200–700 photos, ignoring the chance of getting banned

Level 8: Prostitution - When you pay an unknown 3rd party service to engage in automated reciprocal likes / follows for you, but they use your account to like / follow back

Level 9: Fraud / Heresy - When you buy followers and likes and try to sell yourself to brands as an influencer

The level of botting on social media is so prevalent that if you don’t bot, you will be stuck in Level 1, Limbo, with no follower growth and low engagement relative to your peers.

In economic theory, this is known as a prisoner's dilemma and zero-sum game. If I don’t bot and you bot, you win. If you don’t bot and I bot, I win. If no one bots, everyone wins. But since there is no incentive for everyone not to bot, everyone bots, so no one wins.

Be aware of this and never forget the implications this whole tooling has on social media.

Source: SignalSciences.com

Source: SignalSciences.com

We want to avoid dealing with ethical implications and still work on an automation project here. This is why we will create a simple directory clean-up script that helps you organise your messy folders.

Creating a Directory Clean-Up Script

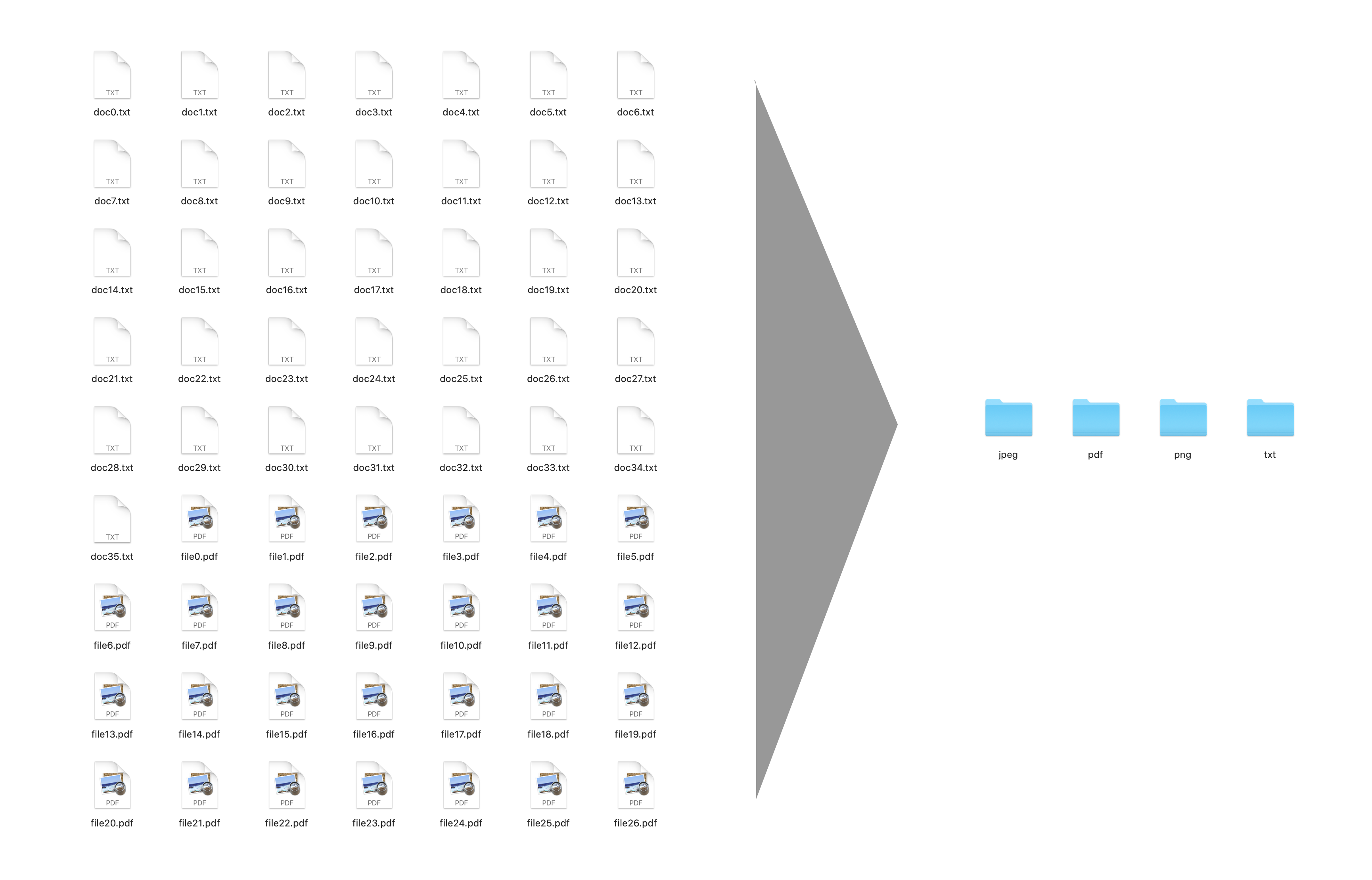

We now want to look at a quite simple script. It automatically cleans up a given directory by moving those files into according folders based on the file extension.

So all we want to do is this:

Setting up the Argument Parser

Since we are working with operating system functionality like moving files, we need to import the os library. In addition to that, we want to give the user some control over what folder is cleaned up. We will use the argparse library for this.

import os

import argparse

After importing the two libraries, let's first set up the argument parser. Make sure to give a description and a help text to each added argument to give valuable help to the user when they type --help.

Our argument will be named --path. The double dashes in front of the name tell the library that this is an optional argument. By default we want to use the current directory, so set the default value to be ".".

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(

description="Clean up directory and put files into according folders."

)

parser.add_argument(

"--path",

type=str,

default=".",

help="Directory path of the to be cleaned directory",

)

# parse the arguments given by the user and extract the path

args = parser.parse_args()

path = args.path

print(f"Cleaning up directory {path}")

This already finishes the argument parsing section – it's quite simple and readable, right?

Let's execute our script and check for errors.

python directory_clean.py --path ./test

=> Cleaning up directory ./test

Once executed, we can see the directory name being printed to the console, perfect.

Let's now use the os library to get the files of the given path.

Getting a list of files from the folder

By using the os.listdir(path) method and providing it a valid path, we get a list of all the files and folders inside of that directory.

After listing all elements in the folder, we want to differentiate between files and folders since we don't want to clean up the folders, only the files.

In this case, we use a Python list comprehension to iterate through all the elements and put them into the new lists if they meet the given requirement of being a file or folder.

# get all files from given directory

dir_content = os.listdir(path)

# create a relative path from the path to the file and the document name

path_dir_content = [os.path.join(path, doc) for doc in dir_content]

# filter our directory content into a documents and folders list

docs = [doc for doc in path_dir_content if os.path.isfile(doc)]

folders = [folder for folder in path_dir_content if os.path.isdir(folder)]

# counter to keep track of amount of moved files

# and list of already created folders to avoid multiple creations

moved = 0

created_folders = []

print(f"Cleaning up {len(docs)} of {len(dir_content)} elements.")

As always, let's make sure that our users get feedback. So add a print statement that gives the user an indication about how many files will be moved.

python directory_clean.py --path ./test

=> Cleaning up directory ./test

=> Cleaning up 60 of 60 elements.

After re-executing the python script, we can now see that the /test folder I created contains 60 files that will be moved.

Creating a folder for every file extension

The next and more important step now is to create the folder for each of the file extensions. We want to do this by going through all of our filtered files and if they have an extension for which there is no folder already, create one.

The os library helps us with more nice functionality like the splitting of the filetype and path of a given document, extracting the path itself and name of the document.

# go through all files and move them into according folders

for doc in docs:

# separte name from file extension

full_doc_path, filetype = os.path.splitext(doc)

doc_path = os.path.dirname(full_doc_path)

doc_name = os.path.basename(full_doc_path)

print(filetype)

print(full_doc_path)

print(doc_path)

print(doc_name)

break

The break statement at the end of the code above makes sure that our terminal does not get spammed if our directory contains dozens of files.

Once we've set this up, let's execute our script to see an output similar to this:

python directory_clean.py --path ./test

=> ...

=> .pdf

=> ./test/test17

=> ./test

=> test17

We can now see that the implementation above splits off the filetype and then extracts the parts from the full path.

Since we have the filetype now, we can check if a folder with the name of this type already exists.

Before we do that, we want to make sure to skip a few files. If we use the current directory "." as the path, we need to avoid moving the python script itself. A simple if condition takes care of that.

In addition to that, we don't want to move Hidden Files, so let's also include all files that start with a dot. The .DS_Store file on macOS is an example of a hidden file.

# skip this file when it is in the directory

if doc_name == "directory_clean" or doc_name.startswith('.'):

continue

# get the subfolder name and create folder if not exist

subfolder_path = os.path.join(path, filetype[1:].lower())

if subfolder_path not in folders:

# create the folder

Once we've taken care of the python script and hidden files, we can now move on to creating the folders on the system.

In addition to our check, if the folder already was there when we read the content of the directory, in the beginning, we need a way to track the folders we've already created. That was the reason we declared the created_folders = [] list. It will serve as the memory to track the names of folders.

To create a new folder, the os library provides a method called os.mkdir(folder_path) that takes a path and creates a folder with the given name there.

This method may throw an exception, telling us that the folder already exists. So let's also make sure to catch that error.

if subfolder_path not in folders and subfolder_path not in created_folders:

try:

os.mkdir(subfolder_path)

created_folders.append(subfolder_path)

print(f"Folder {subfolder_path} created.")

except FileExistsError as err:

print(f"Folder already exists at {subfolder_path}... {err}")

After setting up the folder creation, let's re-execute our script.

python directory_clean.py --path ./test

=> ...

=> Folder ./test/pdf created.

On the first run of execution, we can see a list of logs telling us that the folders with the given types of file extensions have been created.

Moving each file into the right subfolder

The last step now is to actually move the files into their new parent folders.

An important thing to understand when working with os operations is that sometimes operations can not be undone. This is, for example, the case with deletion. So it makes sense to first only log out the behavior our script would achieve if we execute it.

This is why the os.rename(...) method has been commented here.

# get the new folder path and move the file

new_doc_path = os.path.join(subfolder_path, doc_name) + filetype

# os.rename(doc, new_doc_path)

moved += 1

print(f"Moved file {doc} to {new_doc_path}")

After executing our script and seeing the correct logging, we can now remove the comment hash before our os.rename() method and give it a final go.

# get the new folder path and move the file

new_doc_path = os.path.join(subfolder_path, doc_name) + filetype

os.rename(doc, new_doc_path)

moved += 1

print(f"Moved file {doc} to {new_doc_path}")

print(f"Renamed {moved} of {len(docs)} files.")

python directory_clean.py --path ./test

=> ...

=> Moved file ./test/test17.pdf to ./test/pdf/test17.pdf

=> ...

=> Renamed 60 of 60 files.

This final execution will now move all the files into their appropriate folders and our directory will be nicely cleaned up without the need for manual actions.

In the next step, we could now use the script we created above and, for example, schedule it to execute every Monday to clean up our Downloads folder for more structure.

That is exactly what we are creating as a follow-up inside of our Bot Creation and Workflow Automation Udemy course.

A Complete Guide to Bot Creation and Automating Your Everyday Work

Felix and I built an online video course to teach you how to create your own bots based on what we've learned building InstaPy and his Travian-Bot. In fact, he was even forced to take down since it was too effective.

Join right in and start learning.

If you have any questions or feedback, feel free to reach out to us on Twitter or directly in the discussion section of the course ?