I spent a year learning how to build products. Rather, I spent that year learning just how hard it is to build good products.

It's been a roller coaster ride so far and I want to share my learnings.

I'm going to highlight the most important lessons I've learned along the way.

What to Expect from This Article

Before I start, I do want to specify that this blog post is not as technical as most things you will read on freeCodeCamp.

While exploring the technology will be valuable, I believe it is just as beneficial for programmers to look at the business aspect of things. This is in part because it is not something most programmers pay attention to.

As programming becomes more and more popular and commoditized, it will become more valuable for programmers to understand exactly how they are adding value to a company.

Answering the why of problem solving is the most crucial business aspect while building technological solutions.

A Bit of Background and Context

I work at a garment manufacturing company headquartered in Bangalore, India. Nope, you read that right. I work in tech at a garment manufacturing company in Bangalore, India.

Not the most glamorous of jobs, but it does provide a lot of opportunities to experiment.

The garment industry is one of the most unorganized industries in India. For people working in the tech world, it's a little hard to grasp just how unorganized it is.

When people in tech think of a problem, they think of sifting through large sets of data to glean insights that might turn into more effective features.

But, what do you do when the data is still written in pencil on paper? How do you even get access to that information?

Sometimes it feels like the rest of the world stormed ahead leaving certain industries lagging far behind that. And it often feels like the wheel of invention is coming spinning back around again.

How Things Work at the Company

Before I can present the problems, I need to explain how a garment manufacturing unit works.

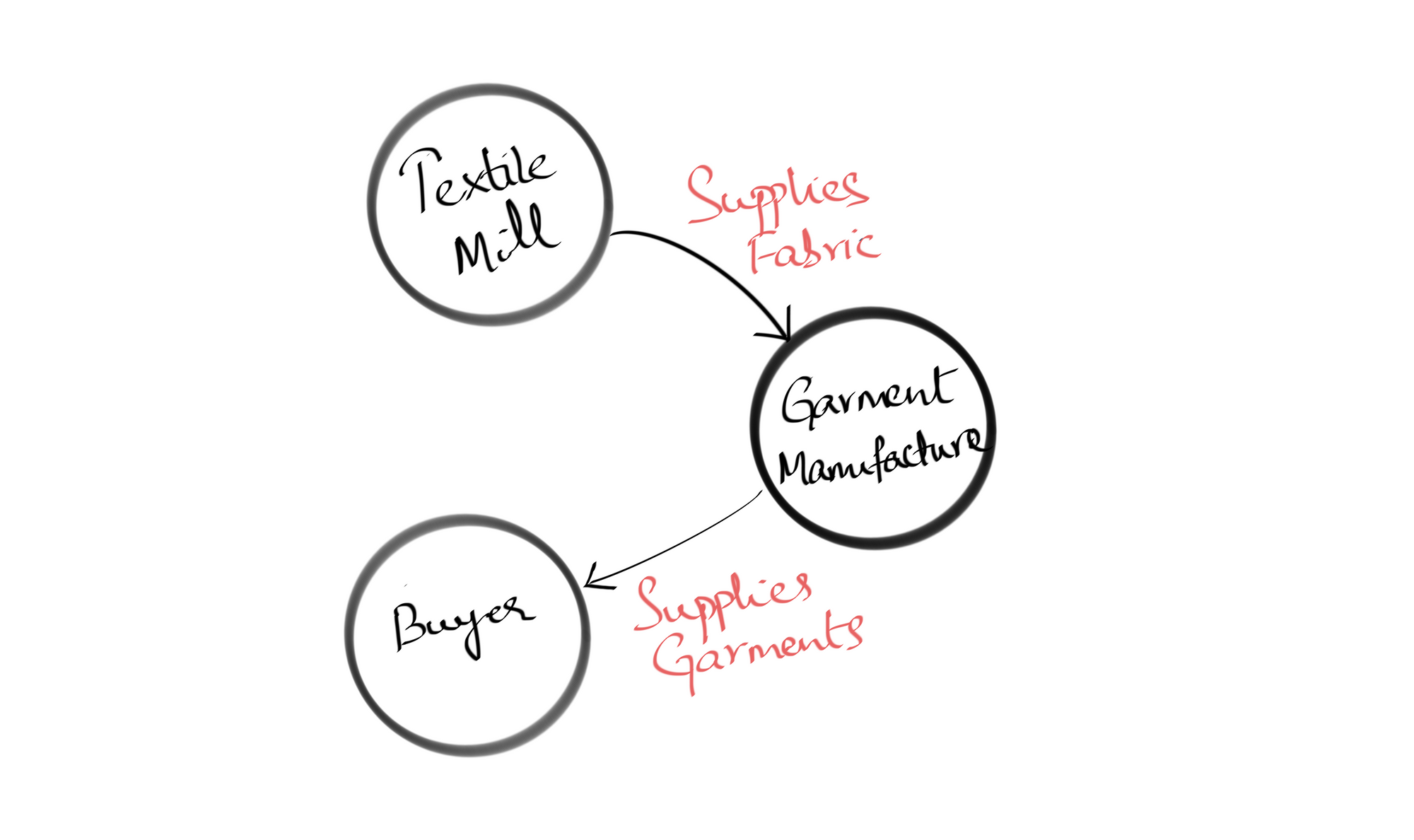

Here is an extremely simplistic overview of how the supply chain in garment manufacturing works

Pretty simple, right? It really is! And just like every other industry, the devil is in the details.

Let's dive in a little deeper. For brevity's sake, let's examine just the relationship between the textile mill and the garment manufacturer.

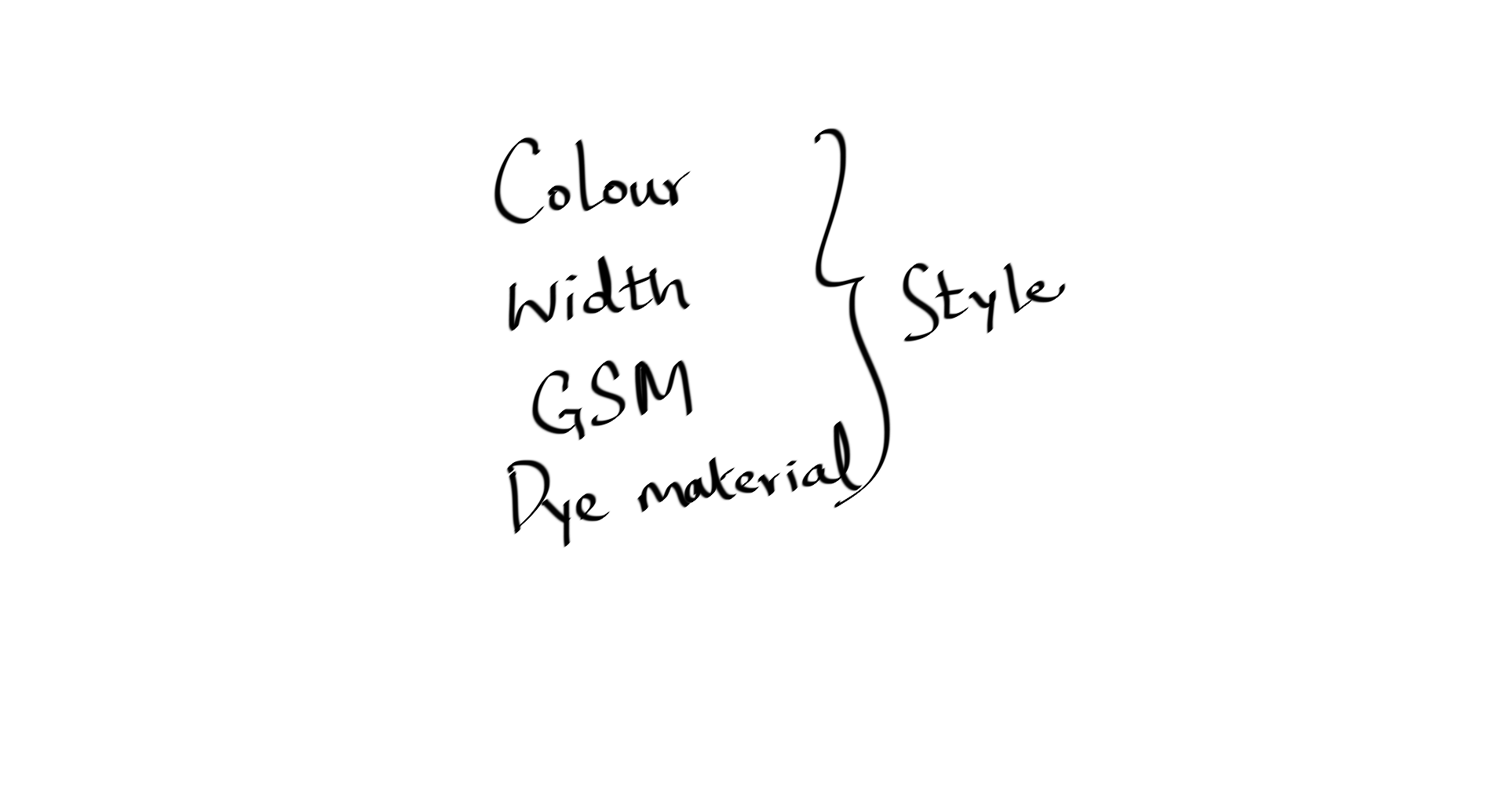

It starts with an order placed by the buyer with the garment manufacturer. The buyer will tell the garment manufacturer that they require a specific kind of fabric for their garments. This is called a style of fabric.

Now, when we refer to the style of fabric, it can mean many different things. Here are a few of the variables that comprise the style of the fabric.

For now, to keep things simple, let's just focus on fabric colour.

The garment manufacturer will then place an order for the fabric with the textile mill. Once the textile mill is ready to ship the fabric, the complexity starts.

The problem is one of scale. When you have over 30 suppliers of fabric, stationed all over a country, keeping track of when you get shipments of fabric is hard.

How We Can Define the Problem

Here are the key problems:

- Keeping track of when you receive the fabric shipment

- Keeping track of how much fabric you've received

- Keeping track of which supplier you've received the fabric from

- Keeping track of which location you've received the fabric at

- Whether the fabric passes quality inspection checks

- Whether the fabric passes the lab tests indicated by the buyer

Our problem is going to focus on only the following three points:

- When did we receive a shipment of fabric from a supplier?

- How much fabric did we receive in a specific shipment?

- At which location did we receive the fabric?

The most obvious solution is Excel sheets.

Lesson #1: In big organizations, Excel functions as a distributed database.

Excel works well, for a while, and then quickly becomes difficult to maintain.

Why? Let's start a hypothetical garment manufacturing company to answer that.

Phase 1

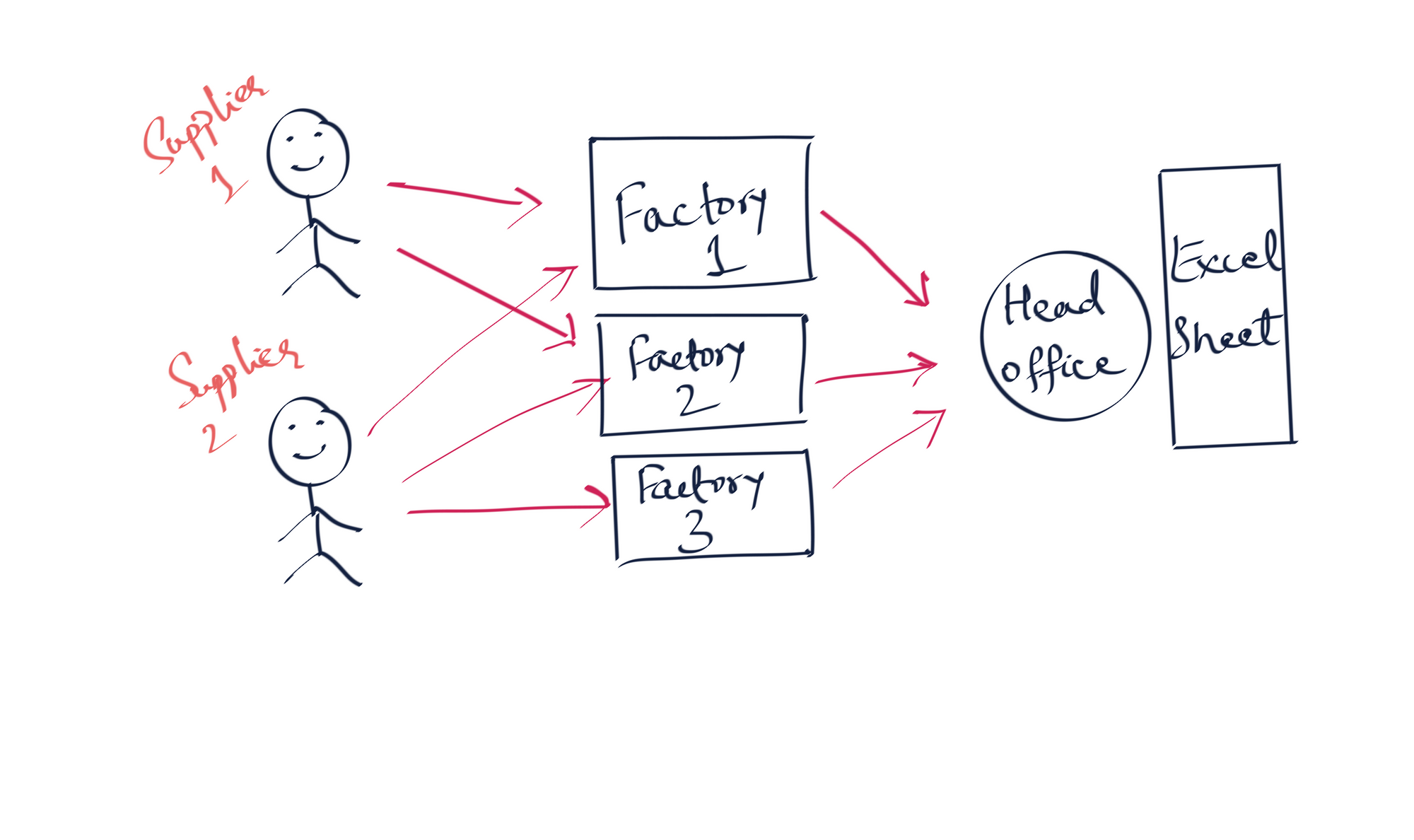

Okay, so we've just started and we have 2 suppliers, 3 factories, and a head office. That's pretty good for a start!

Let's also say that we have 1 buyer. Having a single buyer means that the number of different styles of fabric that we have to deal with are small.

As and when each factory receives fabric, they let the head office know via email the amount of fabric and the style of fabric they received. Then the head office puts that data into an Excel sheet.

Each factory receives fabric once a day, so that means the head office will receive 3 emails a day. Not too bad!

Even if a supplier delays a shipment, it's relatively easy to track because there are only 2 suppliers.

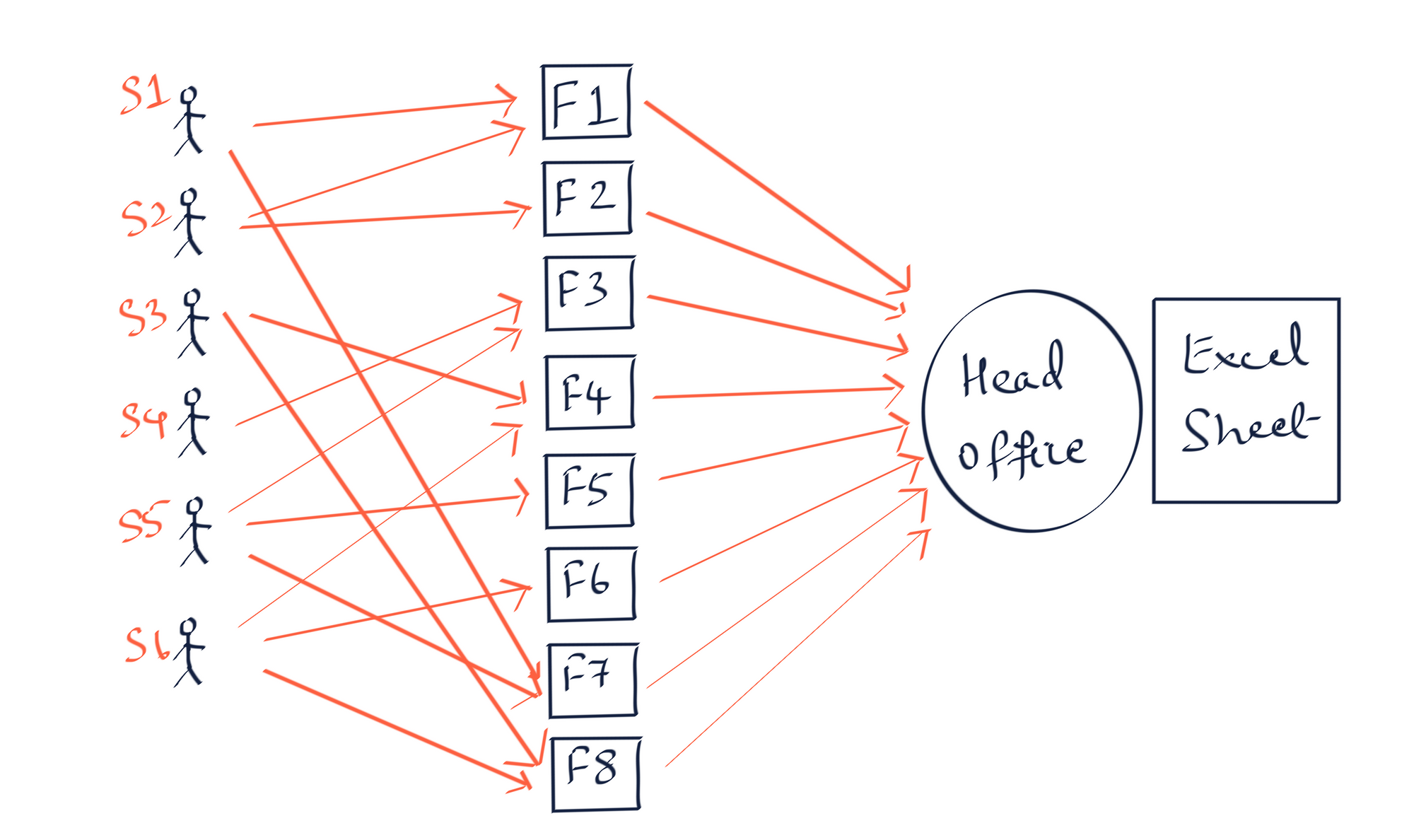

Phase 2

Things are going well, business is growing, and you decide to expand. You set up 5 more factories.

You also increase the number of buyers you're working with, which in turn increases the number of styles of fabric.

You also want to increase your turnover, so 3 of the factories receive fabric twice a day: once in the morning, once in the evening.

Things just got a little more real.

You'll notice that each supplier's face is now invisible. This is not a coincidence. Yeah, I did it to save space but I also did it to illustrate how as scale increases, your personal relationships with business partners take a back seat.

It's simply not possible to maintain the same kind of personal relationship you had with 2 suppliers, with 6 suppliers and 8 factories to boot!

You might wonder why the above point is relevant. That's because it leads into the next lesson.

Lesson #2: Business relationships are built almost entirely on trust, especially in the absence of technology.

Let's examine the lesson above for a bit. It's important because the goal of most technological systems is to eliminate the need for trust. Of course, that's not entirely possible.

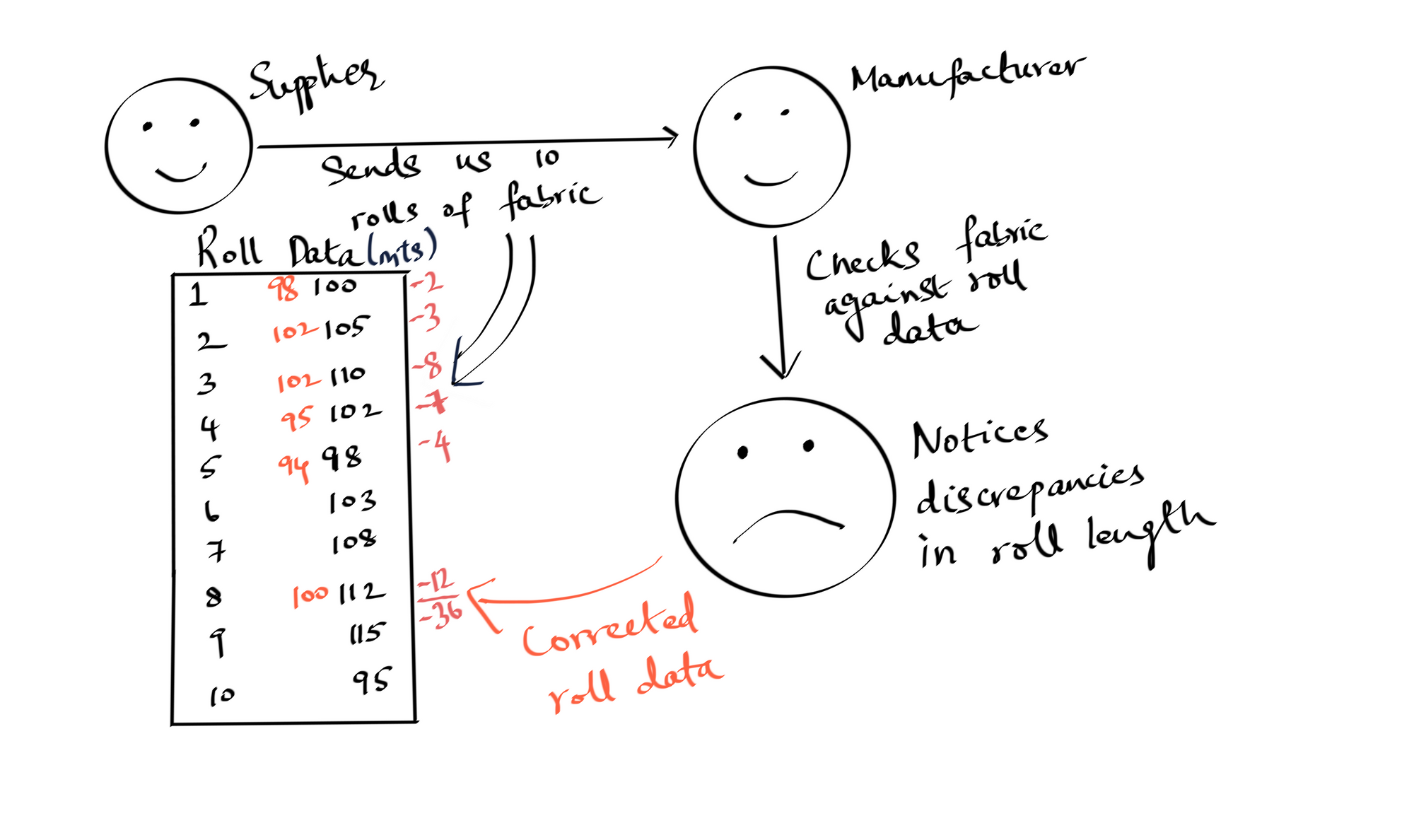

Before continuing, there is one quick thing I need to mention. When suppliers provide fabric to manufacturing units, they usually provide it in the form of a roll of fabric.

Let's construct a scenario with you as a garment manufacturer. You have a supplier who provides you with rolls of fabric.

One time, you receive 10 rolls of fabric and based on an anonymous tip-off decide to measure the length of each roll of fabric against what the supplier tells you it is.

The above infographic shows you what that would look like.

To your dismay, you find out that the supplier is cheating you and you're short 36m of fabric. In a low-margin industry like garment manufacturing, this counts for a lot.

Also, this was only for 10 rolls of fabric. As your company grows, you're going to order more rolls of fabric from a supplier. Imagine you had a 100 rolls of fabric to go through instead of 10.

Manually checking each roll of fabric is not an operation that can scale, and as your operations scale, trust becomes more important.

Now, back to our problems of scaling. We have a total of 6 suppliers, 8 factories, and more buyers – and therefore more styles of fabric.

With 5 factories receiving fabric once a day and 3 factories receiving fabric twice a day, the head office will receive 5*1 + 3*2 = 11 emails a day.

Things have gotten harder not only because the head office is receiving more emails but because the styles of fabric they are receiving have also increased. This adds to the number of rows in an Excel sheet.

Now, when a supplier delays a shipment, things get a lot harder to keep track of because the factories are receiving 11 shipments a day from 6 different suppliers.

But, even now, Excel is not a bad option at all. However, the fabric department is under a lot of strain trying to keep up with the workload, so the head office does what any good organization would do and adds a couple more employees.

Was adding two employees a bad idea? All answers are opinionated.

A technologist would say: "Why would you add two more employees? You need to simplify the process by adding automation!"

A CEO would reply: "Why? The cost of automation is not worth it. It's simpler to add two employees and keep our process the same."

Lesson #3: Not everything is worth automating. This is the hardest lesson to accept for me.

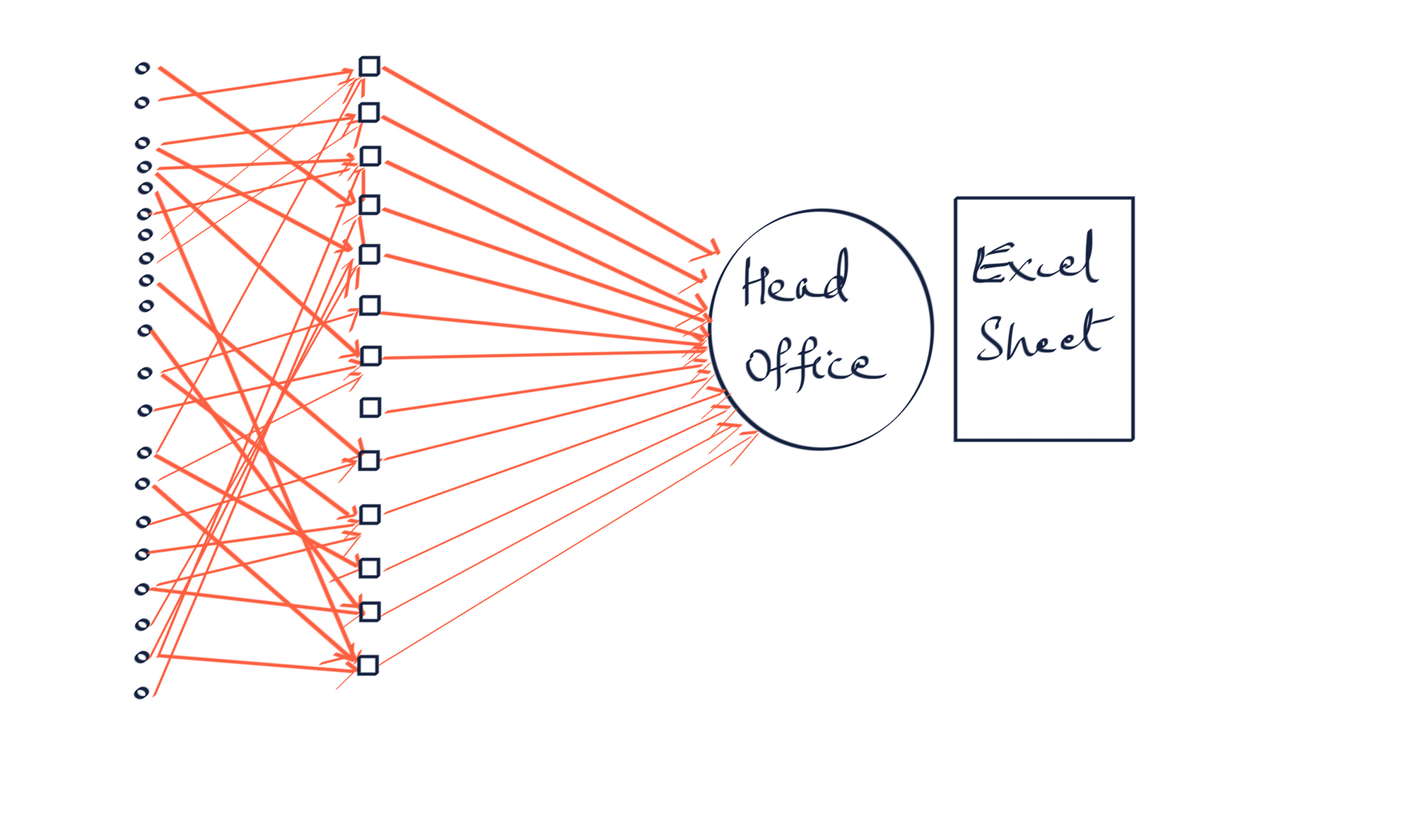

Phase 3

Time passes and business continues to boom. Being a capitalistically inclined CEO, you want to increase the scale of the business again!

This time, you increase the number of factories to 14. You also add more buyers to the portfolio, so this increases the number of styles of fabric the factories need to work with. 6 factories receive fabric twice a day and the remaining 8 receive fabric once a day.

You also work with 20 suppliers now because of all the different styles of fabric you require.

I haven't bothered to name any of the suppliers or the factories in the image above cause it would be too much effort.

But, again, this is to illustrate that the personal relationship you might have had with each of the managers of the factories deteriorates. You simply can't maintain each of those relationships to the same degree.

Now, the head office will receive 8*1 + 6*2 = 20 emails a day! Each email also contains more data because we increased the number of styles we are working with.

Maintaining a manual central Excel sheet becomes harder and harder. Simply adding more employees to the task also won't necessarily help because you might just end up with multiple copies of a centralized Excel sheet in the head office.

How To Solve The Problem

Now, there are multiple ways to solve this problem.

One could be to ask each of the factories to maintain their own daily Excel sheet and send it as an attachment via email to the head office.

However, this again involves someone copying and pasting the data from each factory into one centralized Excel sheet. Nothing wrong with this, but there is probably a more efficient solution.

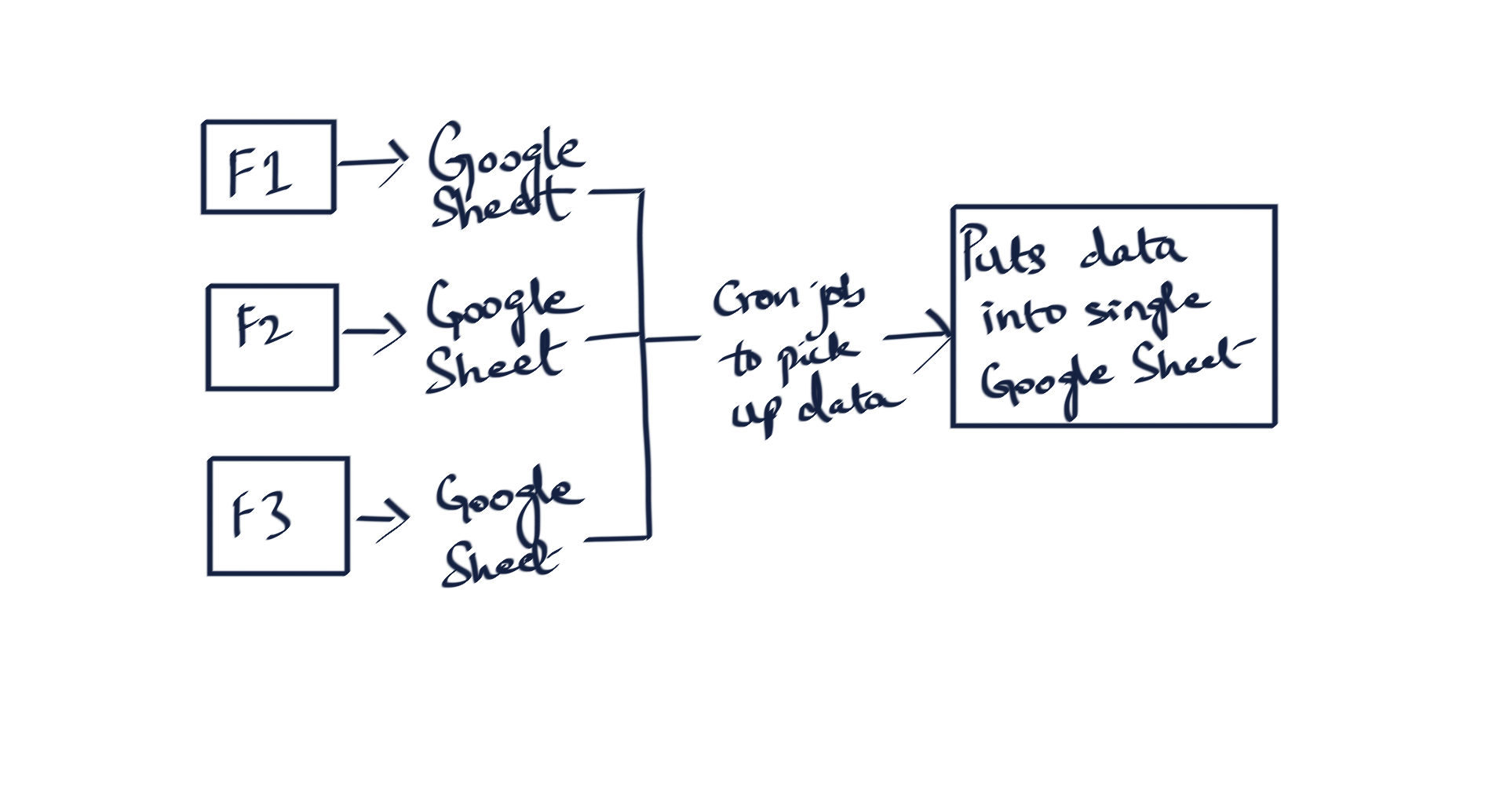

Another potential solution is we could ask each of the units to maintain an individual Google Sheet and run a script using Google App Script every day like a cron job and pick up the data.

However, if you want more data like the length of each roll, you're out of luck. There is no way you can ask people working in factories to manually enter the length of each roll of fabric everyday. Because, like we said earlier, you could potentially receive 150 rolls of fabric a day.

Our Solution

The solution we ultimately went for, at my company, isn't a surprising one: we decided to use barcodes.

We place a barcode on each roll of fabric. The barcode correlates to the length of a roll, the style of fabric, and which buyer it's for.

We built a small Android application that allows users to scan barcodes with the device camera, and on each scan hits an API indicating that this specific barcode was scanned in a specific location (picked up via GPS).

Scanning a roll of fabric allows us to pick up the location of the roll via GPS and the date and time.

Adding up all the rolls of fabric scanned at a location allows us to know the total length of fabric received by a factory.

Best of all, this reduces the workload for the factories themselves. Their only job now is to scan the rolls of fabric. Scanning one roll of fabric takes ~3 seconds, so scanning 100 rolls of fabric takes ~5 minutes.

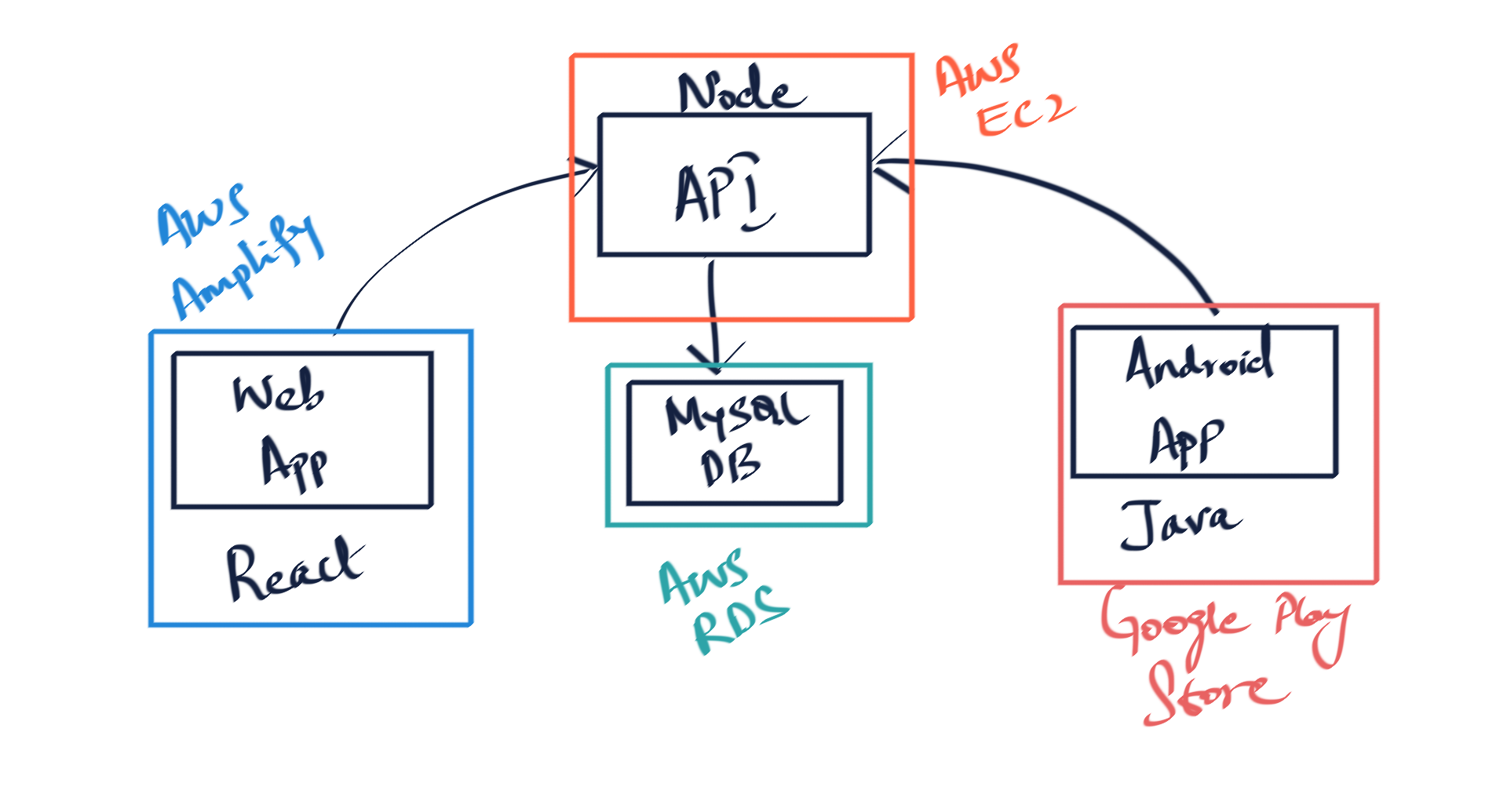

Here is a basic schematic of what we built:

- A web based application that is used to generate the barcodes

- An Android application that is used to scan the barcodes

- An API that both the web app and Android app communicate with. The API in turn communicates with the MySQL DB.

The whole thing is hosted on AWS and the Android app is hosted on Google Play Store.

The solution seems simple enough, but it isn't.

What We Learned From Solving The Problem

Lesson #4: Building things for people is hard because there is often a disconnect between the people building the thing and the people the thing is being built for.

This disconnect is why it's a great idea to build a product that fulfills a need you've long wished existed.

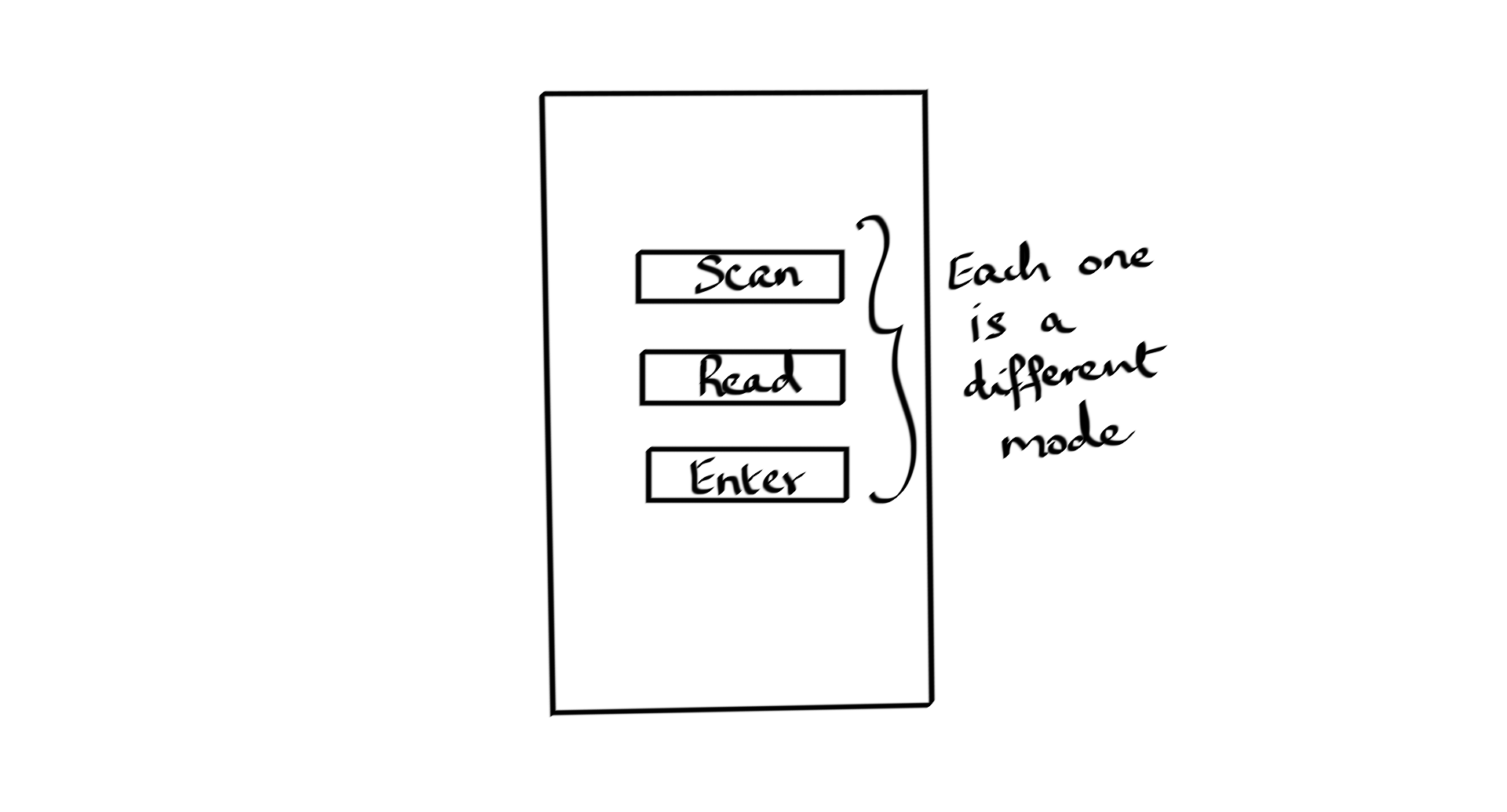

One of the first mistakes we made with the Android app was giving our users too many options

The sketch above shows what a very early verion of our application looked like. Clicking each of those buttons took you to the camera screen. However, each of them made a different API call and so returned a different result.

The rationale for including the Enter button was that, if the barcode were to get scratched and couldn't be picked up by the phone camera, the user could then enter the barcode instead and it would count as a scan.

Here's what one of our barcode numbers looks like: k29_%!s5qG. There is no chance that anybody is going to sit down and enter that sequence of characters.

The rationale for the Read button was that if someone were to want to identify what kind of fabric a specific roll was, they could scan the barcode in Read mode and it would return information about that roll of barcode.

The factories already had their own method of storing information about the roll, though. They just wrote it down in pencil and paper and stuck it to a tag that gets attached to the roll.

Is it the most technologically advanced system? Heck no! But, does it work? Heck yes! And we should have respected the fact that they already had their own way of doing the same operation.

The end result is that almost no one even bothers clicking on either of the Read or Enter buttons.

When building things, keep things to the bare minimum. There is no reason to add additional features unless absolutely required.

The second mistake we made was not knowing our audience.

When we came up with the idea of building a web application for people to use to generate barcodes, it seemed like a no-brainer.

We ran into a funny problem, though.

When we explained to the people working in the factories that they needed to enter the address into the address bar, we got blank looks in response.

You see, with the privileged background most of us come from, we tend to forget that there is a large majority of the population that doesn't know how to interact with a web browser. Why? They've never had the need to. They interact with the internet primarily through smartphone apps.

This might seem like a bit of a stretch but I've seen the evidence with my own eyes. This is not to suggest that people who don't know how to use a browser are less intelligent by any stretch of the imagination. It simply means that we need to communicate things to them differently.

Now, this topic of communication brings me to the final lesson I've learnt. Probably the most hard-earned lesson and definitely the most insightful.

Lesson #5: All problems in an organization are communication problems.

Look back at what we've covered in this article.

The first issue we uncovered was the issue of emails. When an organization is small, fewer emails are exchanged. As an organization scales, the number of emails increases and it becomes harder to keep track. Communication problem.

The second issue we uncovered was one of trust between the supplier and the manufacturer. The supplier communicated wrong/false information to the manufacturer. The manufacturer had to spend valuable time correcting this false information. Communication problem.

The third issue we uncovered was how to explain to people who've never used a web browser, how to navigate to a specific page. Communication problem.

I know it sounds a little like pigeon holing where I'm trying to force every problem into a communication problem, but at the heart of most problems is just that: poor communication.

Conclusion

I glossed over the more technical aspects of the solution we built. However, I think that is not the interesting part. What is interesting is how we've attempted to solve problems.

If you think the problems I am working on are interesting, take a look at our job listings.

If you can't find a role that suits you in the listings, please shoot me a mail at zaid@indian-designs.com.