Have you ever wondered how you can sign in to a website once and remain signed in, even if you close your browser? Or added an item to your shopping cart without signing in at all?

Whether you know it or not, cookies are everywhere, and for better or worse, they completely changed the way we use the web.

In this article, we'll go over the history of cookies, how they work, how to use them in JavaScript, and some security concerns to keep in mind.

A brief history of cookies

HTTP, or the Hypertext Transfer Protocol, is a stateless protocol. According to Wikipedia, its a stateless protocol because it "does not require the HTTP server to retain information or status about each user for the duration of multiple requests."

You can still see this today with simple websites – you type in the URL to the browser, the browser makes a request to a server somewhere, and the server returns the files to render the page and the connection is closed.

Now imagine that you need to sign in to a website to see certain content, like with LinkedIn. The process is largely the same as the one above, but you're presented with a form to enter in your email address and password.

You enter that information in and your browser sends it to the server. The server checks your login information, and if everything looks good, it sends the data needed to render the page back to your browser.

But if LinkedIn was truly stateless, once you navigate to a different page, the server would not remember that you just signed in. It would ask you to enter in your email address and password again, check them, then send over the data to render the new page.

That would be super frustrating, wouldn't it? A lot of developers thought so, too, and found different ways to create stateful sessions on the web.

The invention of the HTTP cookie

Lou Montoulli, a developer at Netscape in the early 90s, had a problem – he was developing an online store for another company, MCI, which would store the items in each customer's cart on its servers. This meant that people had to create an account first, it was slow, and it took up a lot of storage.

MCI requested for all of this data to be stored on each customer's own computer instead. Also, they wanted everything to work without customers having to sign in first.

To solve this, Lou turned to an idea that was already pretty well known among programmers: the magic cookie.

A magic cookie, or just cookie, is a bit of data that's passed between two computer programs. They're "magic" because the data in the cookie is often a random key or token, and is really just meant for the software using it.

Lou took the magic cookie concept and applied it to the online store, and later to browsers as a whole.

Now that you know about their history, let's take a quick look at how cookies are used to create stateful sessions on the web.

How cookies work

One way to think of cookies is that they're a bit like the wristbands you get when you visit an amusement park.

For example, when you sign in to a website, it's like the process of entering an amusement park. First you pay for a ticket, then when you enter the park, the staff checks your ticket and gives you a wristband.

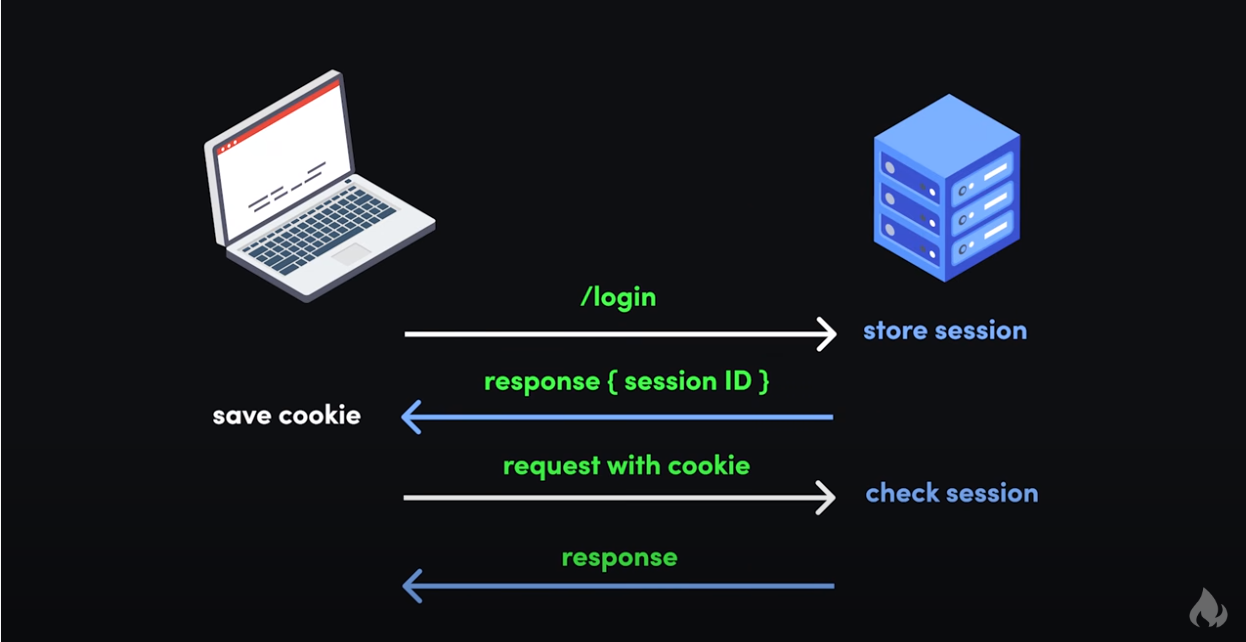

This is like how you sign in – the server checks your username and password, creates and stores a session, generates a unique session id, and sends back a cookie with the session id.

(Note that the session id is not your password, but is something completely separate and generated on the fly. Proper password handling and authentication is outside the scope of this article, but you can find some in depth guides here.)

While you're in the amusement park, you can go on any ride by showing your wristband.

Similarly, when you make requests to the website you're signed in to, your browser sends your cookie with your session id back to the server. The server checks for your session using your session id, then returns data for your request.

Finally, once you leave the amusement park, your wristband no longer works – you can't use it to get back into the park or go on more rides.

This is like signing out of a website. Your browser sends your sign out request to the server with your cookie, the server removes your session, and lets your browser know to remove your session id cookie.

If you want to get back into the amusement park, you'd have to buy another ticket and get another wristband. In other words, if you want to continue using the website, you'd have to sign back in.

This is just a simple example of how cookies can be used to keep you signed in to websites. They can be used to remember your setting for dark mode, to track your behavior on a website, and so much more.

How to use cookies

Now that you know about the history of cookies and why they're used, let's look at some of the limitations of using cookies, then dive into some simple examples.

Cookie limitations

Cookies are quite limited compared to some modern alternatives to storing data in the browser like localStorage or sessionStorage. Here's a rundown of cookies compared to those other technologies:

| Cookies | Local Storage | Session Storage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity | 4KB | 10MB | 5MB |

| Accessible from | Any window | Any window | Same tab |

| Expires | Manually set | Never | On tab close |

| Storage location | Browser and server | Browser only | Browser only |

| Sent with requests | Yes | No | No |

Based on: cookies vs localStorage vs sessionStorage - Beau teaches JavaScript (YouTube)

Cookies are a much older technology, and have a very limited capacity. Still, there's quite a bit you can do with them. And their small size makes it easy for the browser to send cookies with each request to the server.

It's also worth mentioning that browsers only allow cookies to work from one domain for security reasons.

So if you sign in to your bank at, say, ally.com, then cookies will only work within that domain and its subdomains. For example, your ally.com cookie will work on ally.com, ally.com/about, and the subdomain www.ally.com, but not axos.com.

This means that, even if you have accounts and are signed in at both ally.com and axos.com, those sites won't be able to read each other's cookies.

It's important to remember that your cookies are sent with every request you make in the browser. This is very convenient, but has some serious security implications we'll get into later.

Finally, if there's one thing you take away from this article, just remember that cookies are meant to be openly read and sent, so you should never store sensitive information like passwords in them.

How to set a cookie in JavaScript

Cookies are really just strings with key / value pairs. Though you'll probably work with cookies more on the backend, there may be times you'll want to set a cookie on the client side.

Here's how to set a cookie in vanilla JavaScript:

document.cookie = 'dark_mode=true'

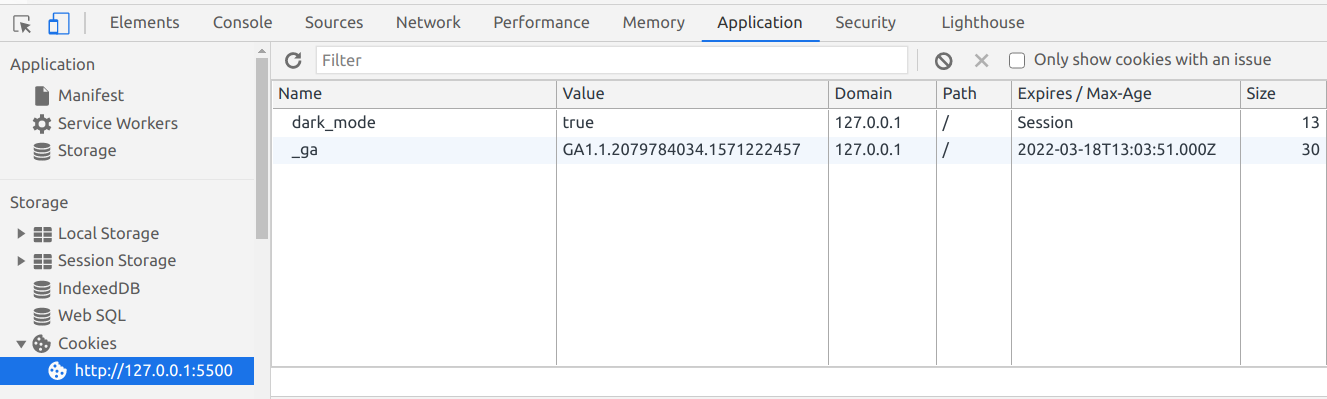

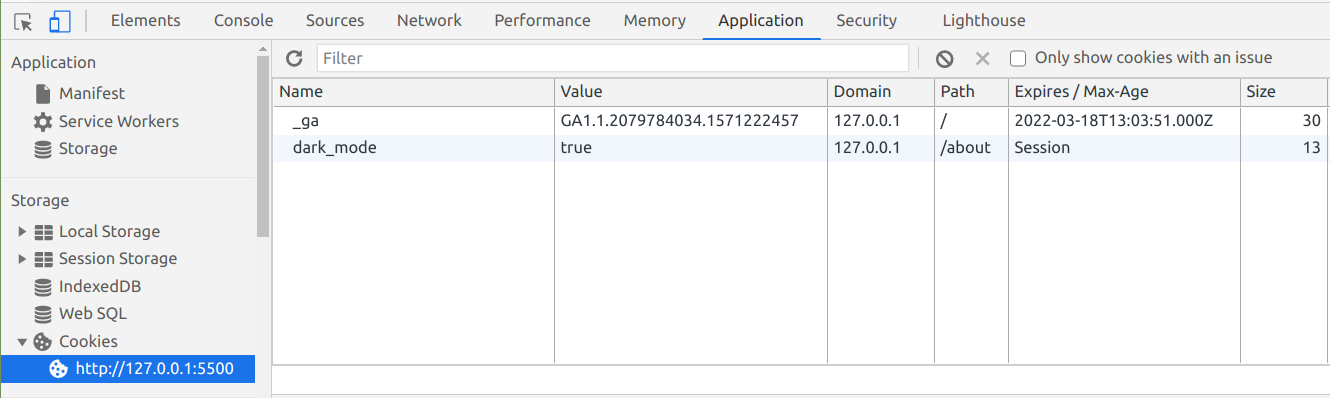

Then when you open the developer console, click "Application" and then on the site under "Cookies", you'll see the cookie you just added:

If you take a closer look at your cookie, you'll see that its expiration date is set to Session. That means the cookie will be destroyed when you close your tab / browser.

That might be the behavior you want, like for an online store with payment information.

But if you want your cookie to last longer, you'll need to set an expiration date.

How to set an expiration date on a cookie in JavaScript

To set an expiration date, just set the value of your cookie, then add an expires attribute with a date set sometime in the future:

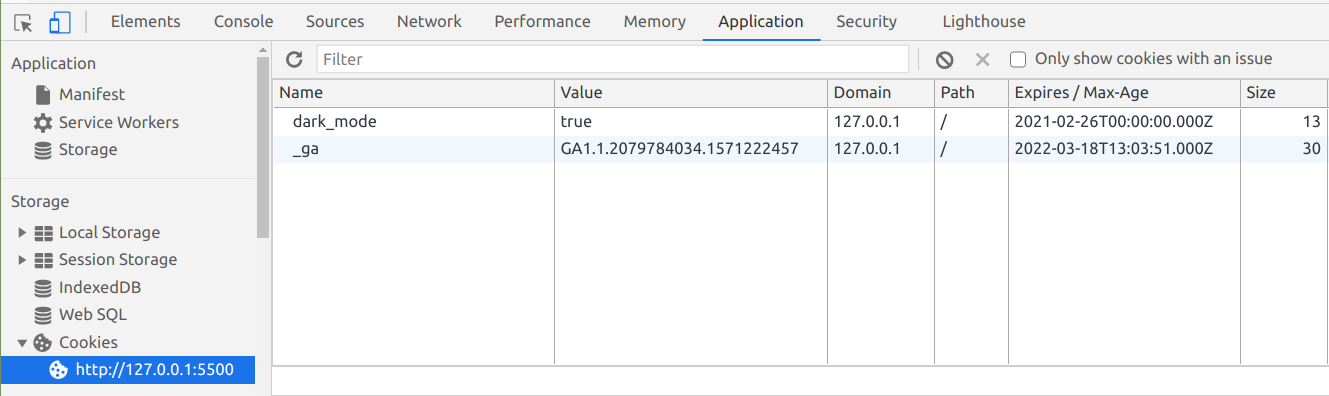

document.cookie = 'dark_mode=true; expires=Fri, 26 Feb 2021 00:00:00 GMT' // expires 1 week from now

JavaScript's Date object should make this much easier and more flexible. You can read more about the Date object here.

Or you could use the max-age attribute with the number of seconds you'd like your cookie to last:

document.cookie = 'dark_mode=true; max-age=604800'; // expires 1 week from nowThen when that date rolls around, the browser will automatically remove your cookie.

How to update a cookie in JavaScript

Whether or not your cookie has an expiration date, updating it is easy.

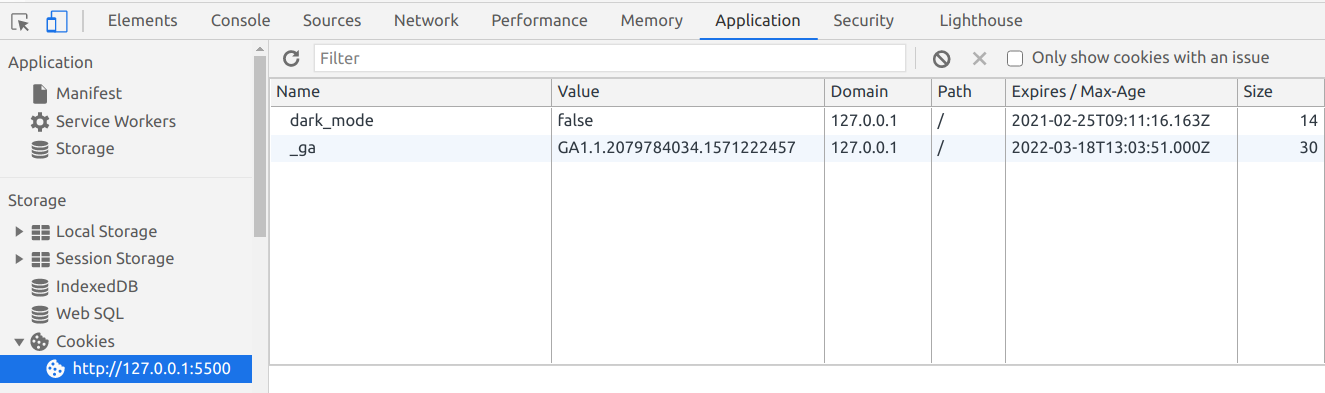

Just change the value for your cookie, and the browser will automatically pick it up:

document.cookie = "dark_mode=false; max-age=604800"; // expires 1 week from now

How to set the path for a cookie in JavaScript

Sometimes you'll only want your cookie to work with certain parts of your website. Depending on how your website is set up, one way to do this is with the path attribute.

Here's how to make it so a cookie only works on the about page at /about:

document.cookie = 'dark_mode=true; path=/about';Now your cookie will only work on /about and other nested subdirectories like /about/team, but not on /blog.

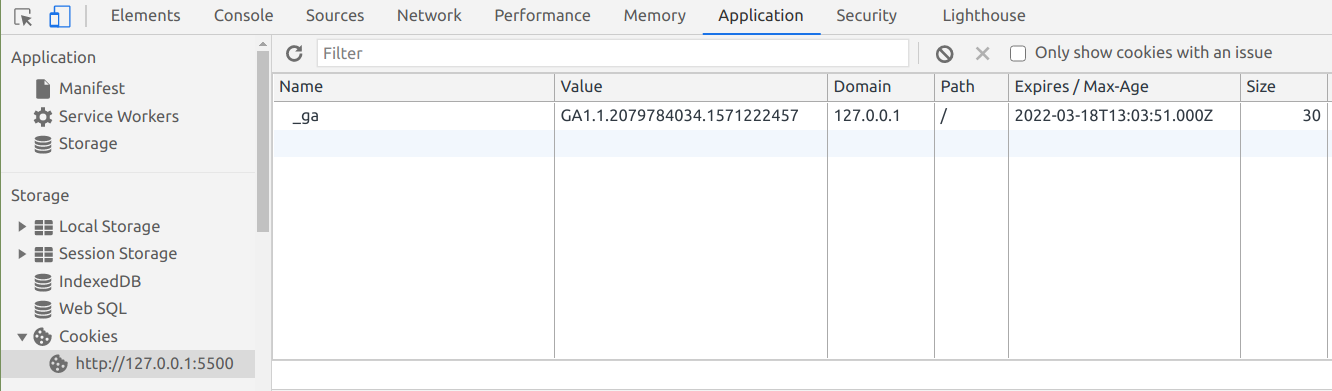

Then when you visit the about page and check your cookies, you'll see it:

How to delete a cookie in JavaScript

To delete a cookie in JavaScript, just set the expires attribute to a date that's already passed:

document.cookie = 'dark_mode=true; expires=Sun, 14 Feb 2021 00:00:00 GMT'; // 1 week earlier

You could also use max-age and pass it a negative value:

document.cookie = 'dark_mode=true; max-age=-60'; // 1 minute earlier

Then when you check for your cookie, it'll be gone:

And that should be everything you need to know about using cookies in vanilla JS.

Everything we covered will work in a pinch, but if you plan on working with cookies extensively, look into libraries like JavaScript Cookie or Cookie Parser.

Security concerns with cookies

In general, cookies are very secure when implemented correctly. Browsers have a lot of built-in limitations that we covered earlier, partly due to the age of the technology, but also to improve security.

Still, there are a few ways that a bad actor can steal your cookie and use it to wreak havoc.

We'll go over some common ways this can happen, and look at different ways to fix it.

Also, note that any code snippets will be in vanilla JavaScript. If you want to implement these fixes on the server, you'll need to look up the exact syntax for your language or framework.

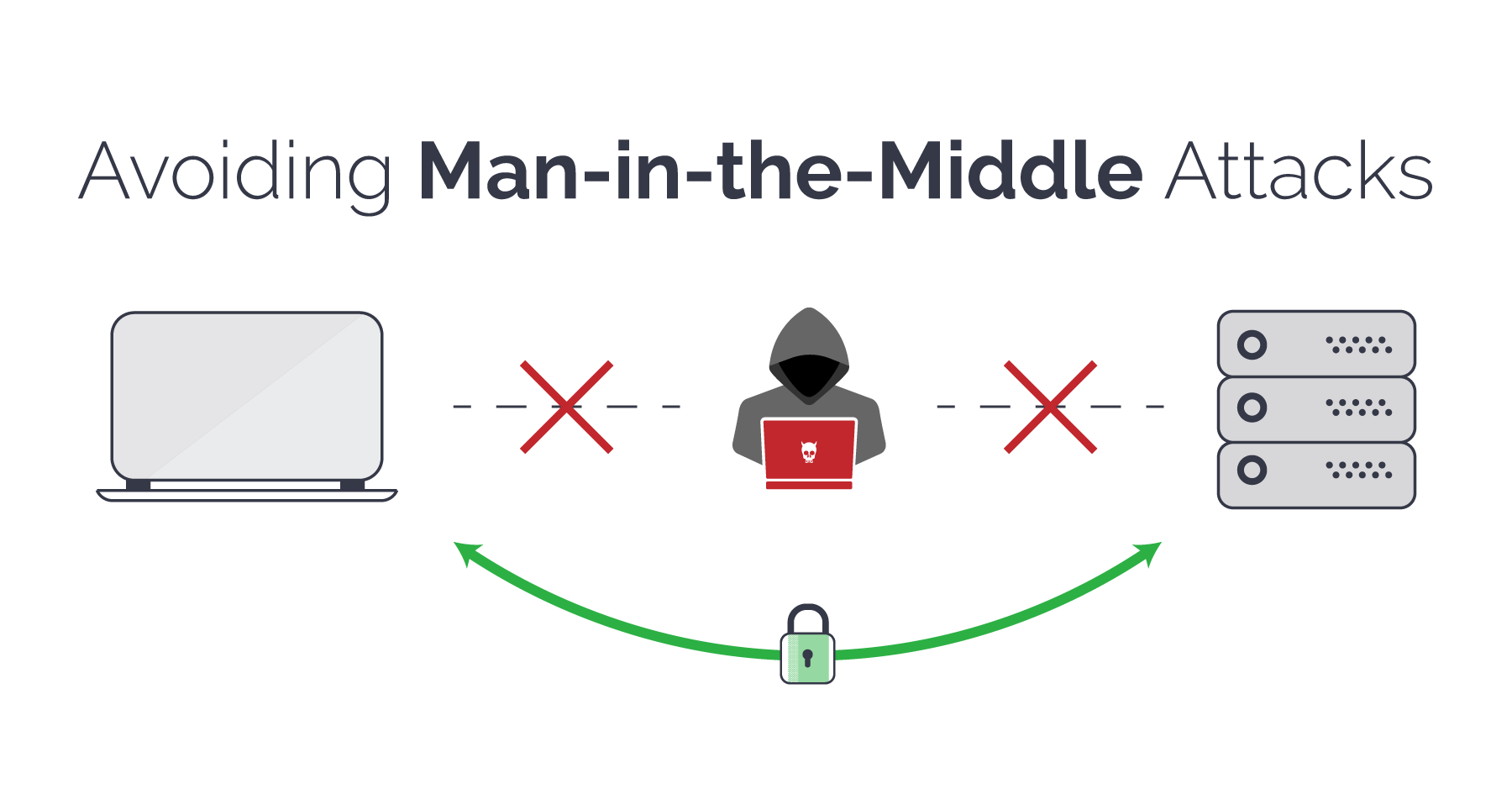

Man-in-the-middle attacks

A man-in-the-middle (MitM) attack describes a broad category of attacks where an attacker sits between a client and a server and intercepts the data going between the two.

This can be done in a lot of ways: by gaining access to or listening in on an insecure website, mimicking a public WiFi router, DNS spoofing, or through malware / adware like SuperFish.

Here's a high-level overview of MitM attacks, and how websites can protect themselves and their users.

Warning: The beginning of the video talks about Mary, Queen of Scotts, and shows an animated depiction of her beheading. It's not overly gruesome, but if you'd like to avoid it, skip ahead to this timestamp:

As a developer, you can greatly reduce the chance of a MitM attack by ensuring that you enable HTTPS on your server, use an SSL certificate from a trusted certificate authority, and ensure your code uses HTTPS instead of the insecure HTTP.

In terms of cookies, you should add the Secure attribute to your cookies so they can only be sent over a secure HTTPS connection:

document.cookie = 'dark_mode=false; Secure';Just remember that the Secure attribute doesn't actually encrypt any data in your cookie – it just ensures that the cookie can't be sent over an HTTP connection.

However, a bad actor could still possibly intercept and manipulate the cookie. To prevent this from happening, you can also use the HttpOnly parameter:

document.cookie = 'dark_mode=false; Secure; HttpOnly';Cookies with HttpOnly can only be accessed by the server, and not by the browser's Document.cookie API. This is perfect for things like a login session, where only the server really needs to know if you're signed into a site, and you don't need that information client side.

XSS attacks

An XSS (cross-site scripting) attack describes a category of attacks when a bad actor injects unintended, potentially dangerous code into a website.

These attacks are very problematic because they could affect every person that visits the site.

For example, if a site has a comments section and someone is able to include malicious code as a comment, it's possible that every person who visits the site and reads that comment will be affected.

In terms of cookies, if a bad actor pulls off a successful XSS attack on a site, they could gain access to session cookies and access the site as another signed in user. From there, they may be able to access the other user's settings, buy things as that user and have it shipped to another address, and so on.

Here's a video that gives a high-level overview of the different types of XSS – Reflected, Stored, DOM-based, and Mutation:

As a developer, you'll want to ensure that your server enforces the Same Origin Policy, and that any input you receive from people is properly sanitized.

And like with preventing MitM attacks, you should set the Secure and HttpOnly parameters with any cookies you use:

document.cookie = 'dark_mode=false; Secure; HttpOnly';CSRF attacks

A CSRF (cross-site request forgery) attack is when a bad actor tricks a person into carrying out an unintended, potentially malicious action.

For example, if you're signed into a site and click on a link in a comment, if that link is part of a CSRF attack, it may lead to you unintentionally changing your sign in details, or even deleting your account.

While CSRF attacks are somewhat related to XSS attacks, specifically reflected XSS attacks where someone inserts malicious code into a site, each preys on a different type of trust.

According to Wikipedia, while XSS "exploits the trust a user has for a particular site, CSRF exploits the trust that a site has in a user's browser."

Here's a video that explains the basics of CSRF, and gives some useful examples:

As for cookies, one way to prevent possible CSRF attacks is with the SameSite flag:

document.cookie = 'dark_mode=false; Secure; HttpOnly; SameSite=Strict';

There are a few values you can set for SameSite:

Lax: Cookies are not sent for embedded content (images, iframes, etc.) but are sent when you click on a link or send a request to the origin the cookie is set for. For example, if you're ontesting.comand you click on a link to go totest.com/about, your browser will send your cookie fortest.comwith that requestStrict: Cookies are only sent when you click on a link or send a request from the origin the cookie is set for. For example, yourtest.comcookie will only be sent while you're in and aroundtest.com, and not coming from other sites liketesting.comNone: Cookies will be sent with every request, regardless of context. If you setSameSitetoNone, you must also add theSecureattribute. It's better to avoid this value if possible

Major browsers handle SameSite a bit differently. For example, if SameSite isn't set on a cookie, Google Chrome sets it to Lax by default.

Alternatives to cookies

You might be wondering, if there are so many potential security flaws with cookies, why are we still using them? Surely there must be a better alternative.

These days, you can use either sessionStorage or localStorage to store information that originally used cookies. And for stateful sessions, there's token-based authentication with things like JWT (JSON Web Tokens).

While it may seem like you have to choose between cookie-based or token-based authentication, it's possible to use both. For example, you might want use cookie-based authentication when someone signs in through the browser, and token-based authentication when someone signs in through a phone app.

To muddy the waters a bit more, authentication-as-a-service providers like Auth0 allow you to do both types of authentication.

If you'd like to learn more about web tokens and token-based authentication, check out some of our articles here.

When you give a developer a cookie

That's it! That should be just about everything you need to know to get started with using cookies, and what to watch out for along the way.

Did you find this useful? How do you use cookies? Let me know over on Twitter.