by Preethi Kasireddy

How the Web Works Part III: HTTP & REST

We went over basic web architecture in part I, and we talked about web application structure in part II. Now it’s time to roll up our sleeves and tackle part III: a closer look at HTTP and REST.

Understanding HTTP is crucial for web developers because it facilitates the flow of information in web applications — allowing better user interactions and improved site performance.

What is HTTP?

In the Client-Server model, clients and servers exchange messages in a “request–response” messaging pattern: the client sends a request and the server returns a response.

Keeping track of those messages is trickier than it sounds, so the client and server adhere to a common language and set of rules so they know what to expect. This language, or “protocol,” is called HTTP.

The HTTP protocol defines the syntax (the data format and encoding), semantics (the meaning associated with the syntax) and timing (speed and sequencing). Each HTTP request and response exchanged between a client and server is considered a single HTTP transaction.

HTTP: The broad strokes

There are a few things worth noting about HTTP before we dive into the details.

First off, HTTP is text-based, meaning that the messages exchanged between the client and server are bits of text. Each message contains two parts: a header and a body.

Secondly, HTTP is an application layer protocol, meaning it’s just an abstraction layer that standardizes how hosts communicate. HTTP itself doesn’t transmit the data. It still depends on the underlying TCP/IP protocol to get the request and response from one machine to another.

(As a reminder, TCP/IP is a two-part system that functions as the Internet’s fundamental “control system”. For more on TCP/IP, check out Part I)

Lastly, you may have seen the protocol “HTTPS” in the address bar on your browser and wondered whether HTTP is the same thing as HTTP + “S”. The short answer is sorta, with a slight difference.

A plain HTTP request or response is not encrypted and is vulnerable to various types of security attacks. HTTPS, on the other hand, is a more secure communication that uses encryption to keep things safe. It stands for HTTP over TLS/SSL.

SSL is a security protocol that allows the client and server to communicate across a network in a secure way — to prevent eavesdropping and tampering — while the message travels across the network.

The client typically indicates whether it needs a TLS/SSL connection by using a special port number: 443. Once the client and server agree to use TLS/SSL to communicate, they negotiate a stateful connection by doing what’s called a “TLS handshake.” The client and server then establish secret session keys that they can use to encrypt and decrypt messages as they talk to each other.

Many major websites like Google and Facebook use HTTPS — after all, it’s what keeps your passwords, personal information and credit card details safe on the wire.

HTTP: The fine strokes

With those basics out of the way, let’s dive a little deeper into the structure of HTTP.

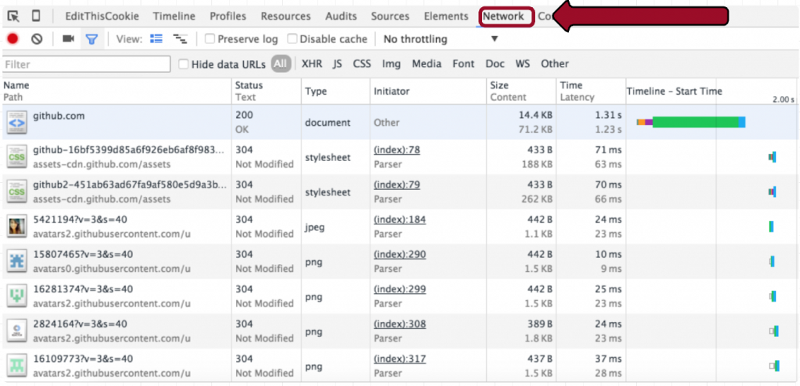

We can start by visiting https://www.github.com to communicate with a GitHub server. If you’re using Chrome or Firefox with the Firebug extension installed, you can investigate the details of HTTP requests by going to the “Network” tab. If you have this open, then visit www.github.com by typing it into your address bar and you should see something like this:

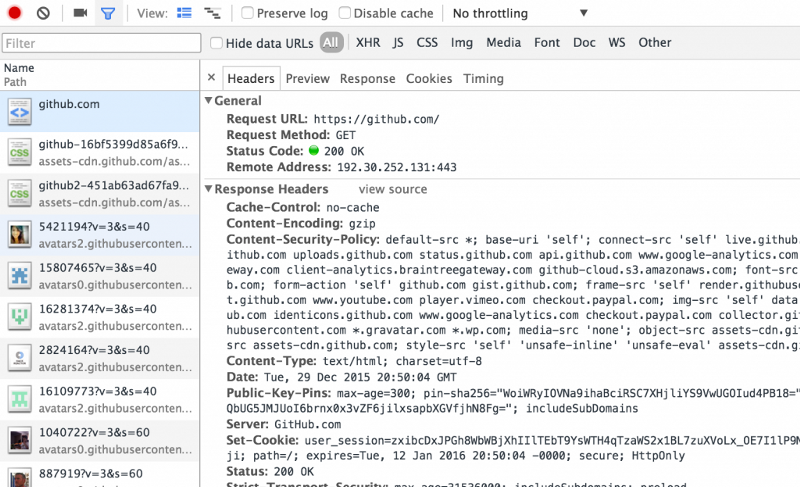

Then on the left panel, click on the first path, “github.com.” You should now see this:

HTTP Request Header

HTTP Headers typically contain metadata (data about data). The metadata includes request type (GET vs. POST vs. PUT vs. DELETE), path, status code, content-type, user-agent, cookie, post body (sometimes), and more.

Let’s take a closer look at the most important parts of the header using the Github example, starting with the “response headers” section:

- Request URL:https://github.com/

- The URL we requested

- Request Method:GET

- The type of HTTP method being used. In our case, our browser said: “Hey, Github’s server, GET me to your homepage.”

- Status Code:200 OK

- A standardized way for the server to tell the client about the result of its request. Status code 200 means that the server successfully found the resource, and is sending it to you.

- Remote Address:192.30.252.129:443

- The IP address and port number of the GitHub website we visited. Note that it’s port # 443 (which means we’re using HTTPS instead of HTTP).

- Content-Encoding:gzip

- The encoding of the resource we received back. In our case, Github’s server is telling us that the content it’s sending back is compressed. Github is probably compressing the file so that you can have faster download time.

- Content-Type:text/HTML; charset=utf-8

- Specifies the representation of the data in the response body, including the type and subtype. The type describes the type of data, while the subtype specifies a specific format for that type of data. In our case, we have text being sent back in the form of HTML

- The second part specifies the character encoding for the HTML document. This will most often be UTF-8, as is the case above.

There’s also a bunch of header information, which the client had to send so that the server could know how to respond. Take a look under the “request headers” portion:

- User-Agent:Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_10_5) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/47.0.2526.73 Safari/537.36

- The software that is acting on behalf of a user. Sometimes a website needs to know how it is being viewed. So the browser sends this User-Agent string that the server can use to determine what is being used to access a website

- Accept-Encoding:gzip, deflate, sdch

- Specifies what content encoding the browser is willing to accept. We can see that gzip is listed, and that’s why Github’s server was able to send us the content in gzip format.

- Accept-Language:en-US,en;q=0.8

- Describes the language we want the webpage to be in. In our case, “en” stands for English.

- Host:github.com

- Self-explanatory :)

- Cookie:_octo=GH1.1.491617779.1446477115; logged_in=yes; dotcom_user=iam-peekay; _gh_sess=somethingFakesomething FakesomethingFakesomethingFakesomethingFakesomethingFakesomethingFakesomethingFake; user_session=FakesomethingFake somethingFakesomethingFakesomethingFake; _ga=9389479283749823749; tz=America%2FLos_Angeles_

- A piece of text that a web server can store on a user’s machine and later retrieve. The information is stored as name-value pairs. One of the name-value pairs that Github stored for my request, for example, is “dotcom_user=iam-peekay”, which informs Github that my userid is iam-peekay.

tl;dr: what’s up with all these name-value pairs?

Long story short, we’re left with a lot of name-value pairs. But how do these name-value pairs get created?

Anytime your browser visits a website, it’ll look on your computer for a cookie file set by the website earlier.

So if I’m visiting www.github.com, my browser will look for a cookie file that GitHub has saved on my hard disk. If it finds a cookie file, it’ll send all of the name-value pairs in the request header.

GitHub’s web server can now use the cookie data in many different ways, such as rendering content based on my stored user preferences, counting the number of time I visited their site.

If the browser doesn’t find a cookie file — either because the site has never been visited before or the user blocked or deleted it — the browser doesn’t send any cookie data.

In this case GitHub’s server creates a new ID as a name-value pair, along with any other name-value pairs it wants, and sends it to my computer via the HTTP header — which my computer then stores on its hard disk.

HTTP Body

As you saw above, the server holds most of the important “metadata” (data about data) that it needs to communicate with the client.

Now onto the body.

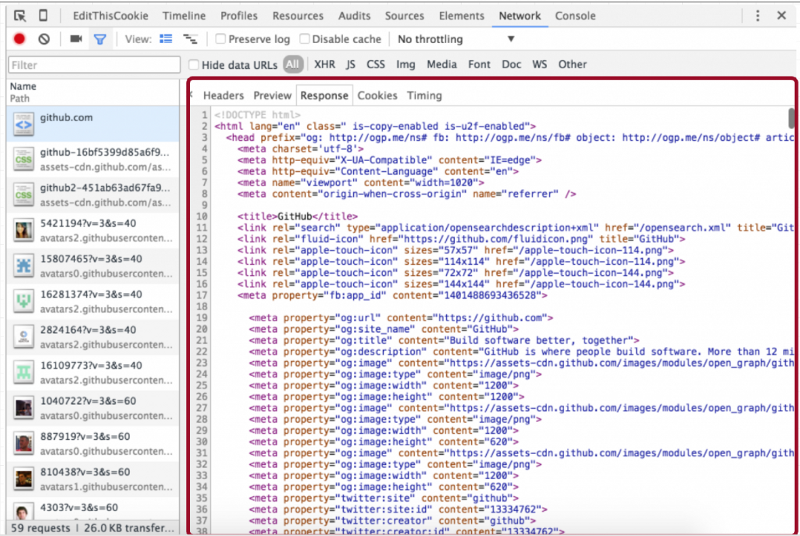

The body, as you might guess, is the body of the message. Depending on the type of request, it can be empty.

In our case, you can see the body in the “Response” tab. Since we made a GET request to www.github.com, the body contains the HTML page content for www.github.com.

…Which is, of course, important for displaying that page.

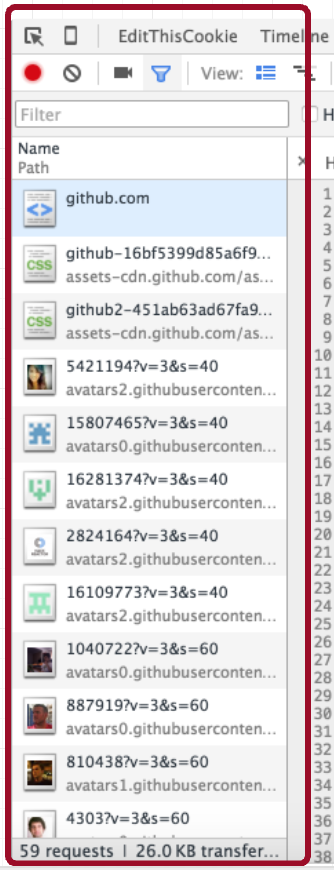

Additional exercises

I hope that this leaves you with a better understanding of the structure of HTTP. For practice, you can take a look at all the other assets that are requested by your browser (images, JavaScript files, etc.) when you visit www.github.com.

With that out of the way, let’s look at the various types of HTTP methods that a client can initiate.

HTTP Methods

HTTP verbs, or methods, tell the server what to do with the data identified by the URL. URLs always identify a specific resource. When a client uses a URL in combination with an HTTP verb, this tells the server what action needs to happen on which resource.

Examples of URLs include:

- GET http://www.example.com/users (get all users)

- POST http://www.example.com/users/a-unique-id (create a new user)

- PUT http://www.example.com/comments/a-unique-id (update a comment)

- DELETE http://www.example.com/comments/a-unique-id (delete a comment)

When a client makes a request, it’ll indicate the type of request using one these verbs. The most important ones are GET, POST, PUT and DELETE. There are other methods, such as HEAD and OPTIONS, but they are rarer, so we’ll skip those for this post.

GET

GET is the most commonly used method. It’s used to read information for a given URL from a server.

GET requests are read-only, meaning that the data should never be modified on the server — the server should simply retrieve the data unchanged. In this way, GET requests are considered safe operations, because calling it once, or calling it 20 times, will have the same effect.

Additionally, GET requests are idempotent. What this means is that submitting multiple GET requests to the same URL should cause the exact same effect as just one GET request since a GET request is just asking the server for data and not actually changing any data on the server.

GET requests respond with a status code 200 (OK) if the resource was successfully found, and 404 (NOT FOUND) if the resource was not found. (Hence the term “404 page” for error messages when visiting retired or mis-typed URLs.)

POST

POST is used to create a new resource, such as a sign-up form. You use POST when you want to create a subordinate resource (e.g. a new user) to some other parent resource (http://example.com/users). Your post to this parent resource identified by the URL, and the server processes the new resource and associates it with the parent.

POST is neither safe nor idempotent. This is because making two or more identical POST requests will likely cause two new identical resources to be created.

POST requests respond with a status code 201 (CREATED) along with a location header with the link to the newly created resource.

PUT

PUT is used to update the resource identified by the URL using the information in the request body. PUT can also be used to create a new resource. PUT requests are not considered safe operations because they modify state on the server. However, it is idempotent because multiple identical PUT requests to update a resource should have the same effect as the first one.

PUT requests respond with a status code of 200 (OK) if the resource was successfully updated, and 404 (NOT FOUND) if the resource was not found.

DELETE

DELETE is used to delete the resource identified by the URL. DELETE requests are idempotent because if you DELETE a resource, it’s deleted and even if you make multiple identical DELETE requests, the result is the same: a deleted resource.

You’ll likely just get a 404 error message if you send a DELETE request more than once for the same resource, because the server won’t be able to find it once it’s been deleted.

DELETE requests respond with a 200 (OK) status code if successfully deleted or 404 (NOT FOUND) if the resource to be deleted couldn’t be found.

All of the above requests return a 500 (INTERNAL SERVER ERROR) if the processing fails and the server errors out.

What is REST after all?

I have one last term to cover before we call it a day: REST.

You may have heard the term “RESTful application” before. It’s important to understand what this means because if you’re using HTTP to communicate between the client and server, it’s beneficial to follow the REST guidelines. (In fact, the HTTP verbs we defined above represent a majority of what REST is.)

REST stands for “Representational State Transfer.” It’s an architecture style for designing applications.

The basic idea is that you use a “stateless”, “client-server”, “cacheable” protocol to make calls between machines — and most often, this protocol is HTTP. This is just a fancy way of saying that REST gives you a set of constraints to design an application with. These constraints help make the system more performant, scalable, simple, modifiable, visible, portable, and reliable.

The full list of constraints is lengthy and you can read more about it here. For the sake of this post, I’d like to double-click on the two most important ones:

- Uniform interface: This constraint tells you how to define the interface between the client and server in a way that simplifies and decouples the architecture. It says that:

- Resources must be identifiable in a request (e.g. by using resource identifiers in the URI). A resource (e.g. data in a database) is the data that defines the resource representation (e.g. JSON, HTML). Resources and resource representations are separate things — the client only interacts with the resource representation.

- The client must have enough information to manipulate resources on the server using the representation of the resource.

- Every message exchanged between the client and server needs to be self-descriptive, with information on how to process the message.

- Clients must send state data using HTTP body content, HTTP request headers, query parameters and the URL. Servers must send state data using HTTP body content, response codes, and response headers.

- NOTE: The HTTP verbs we described above make up a major portion of this “uniform interface” constraint, because they represent the uniform actions that happen on resources.

2. Stateless: This constraint says that all the state data needed to handle a client request must be contained within the request itself (URL, query parameters, HTTP body, or HTTP headers) and the server must send all the state data necessary back to the client through the response itself (HTTP headers, status code, and HTTP response body).

Side note: State — or application state — is the data necessary for a server to fulfill a request.

What this means is that the for every request, we resend the state information back and forth, so that the server doesn’t have to maintain, update and send the state.

Having such a stateless system makes applications a whole lot more scalable, because no server has to worry about maintaining the same session state over the span of multiple requests. Everything needed to get the state data is available in the request and response itself.

Closing remarks

Phew! HTTP is far from simple. But as you can see, it’s a critical component of the client-server relationship.

Making RESTful applications require at least a basic understanding of HTTP . With this content under your belt, you’re well on your way to deciphering the mysteries of client-server communication in your next coding project.