Your backlog is full of detailed user stories. Your team is no longer able to manage them, or rank them.

You wonder what the product you’re building is all about. The stakeholders seem to change their mind all the time. You miss the big picture.

I think you are in Story Card Hell, as James Shore says.

Here are three ways to escape.

Product vision

A vision states a goal. But it does not tell you how to reach it.

A great vision is challenging and inspiring. It transcends the individual. It brings people together to work towards it. It motivates them.

The company vision of SpaceX, Elon Musk’s aerospace company, is:

SpaceX designs, manufactures and launches advanced rockets and spacecraft. The company was founded in 2002 to revolutionize space technology, with the ultimate goal of enabling people to live on other planets.

The product vision of Apple’s iPod was:

All my music in my pocket.

Usually, a product manager/owner will come up with the product vision. So if you don’t know the vision, talk with your product manager.

If you are a product manager: how would you pitch your product to a potential investor in 30 seconds?

You can build a Product Vision Box together with other stakeholders. Take cardboard and build a box. Write and draw on the surface. How would the hypothetical product packaging look? The limited space will force you to focus on the top features of your product.

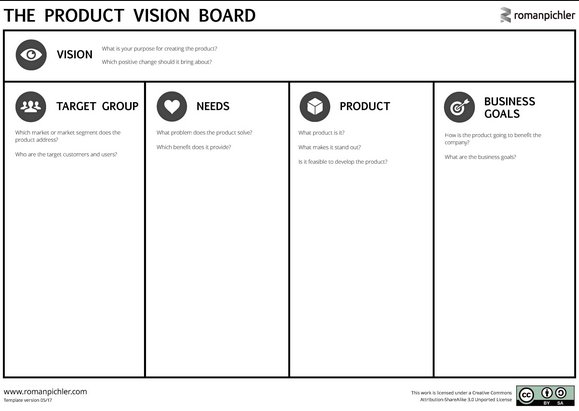

For a more sophisticated description of the vision, you can use a Product Vision Board:

The Product Vision Board explains:

- The target group (who will use the product)

- The needs (of the users)

- The product (key features)

- The business goals (e.g. how is the company making money from the product?)

How does a product vision help you to escape from Story Card Hell?

A vision gives direction. That’s why you should make it visible where development happens. Create a huge poster, for example, and hang it on the wall.

Everybody can check if new stories fit the product vision. And challenge stories that deviate from the intended direction.

Big picture

Even if you have a vision, you may miss contextual information for your stories. This is the big picture.

There are several practices that help you understand the big picture. One of these practices is Story Mapping by Jeff Patton. Below you’ll find the way I practice it.

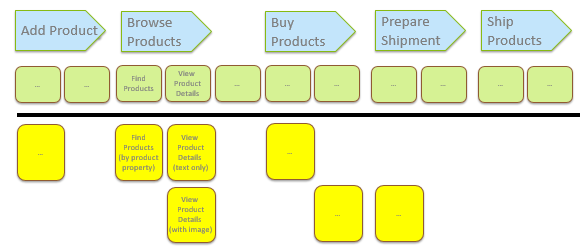

User activities are at the top. Frame an activity by a goal certain users want to reach. It can be for their own benefit or to get their job done. Order activities from left to right. The more to the left, the earlier the activity takes place.

Example activities of an online shop are: Add Product, Browse Products, Buy Products, Prepare shipment, Ship products. In most cases, a user performs an activity in a single sitting. Often in a matter of minutes or at most hours.

To reach a goal, users need to do stuff: the user tasks. Example tasks are Find Products and View Product Details for the Browse Products activity.

Together with the activities, the tasks represent the backbone. This is the structure you use to organize the stories.

From the tasks, you derive stories. From the View Product Details task, you could derive a story titled View Product Details (text only) and another story titled View Product Details (with image).

The higher the team places a story, the earlier the team implements it. Implementation moves from left to right in a row, and from top to bottom.

Do not store a Story Map in an electronic tool. Instead, put it up on a wall and use it to communicate within the team, with users, and with other stakeholders. Leave it hanging there, and you’ll always see the context of the stories.

Other practices to understand the context of stories include:

Just-in-time specification

A crucial practice to escape from Story Card Hell is just-in-time specification. Only detail the stories for the next one to two sprints. Let’s walk through an example.

The product manager writes a story card:

As a customer, I want to find products by a property to know that the shop offers what I want.

The product manager has something specific in mind. The users should be able to search by product name, product number, product category, and price.

A week before the sprint starts, the product manager talks with the team about the idea. The developers tell her that another team released a powerful search feature a few days ago, for a different product.

It’s based on a simple text field, like Google. It would be less effort to reuse it than to develop something new. The team agrees on that, and writes down what they agreed upon as acceptance criteria.

So the team documents the details of the story shortly before implementation. That way, the team has as much knowledge from previous development as possible.

Conclusion

There are several practices to escape from Story Card Hell:

- A product vision sets a goal and helps to keep development on track.

- Story Mapping provides a big picture as context for the stories.

- Just-in-time specification makes sure that you detail only the most clearly understood stories.

In the best case, you use all the practices. For this to work, you likely need a product manager who

- Fosters the relationships to the stakeholders

- Is good at communication and conflict resolution

- Is not afraid to say “No” from time to time

Learn how to apply this strategy in practice by visiting my online course.