The thing I love most about programming is the aha! moment when you start to fully understand a concept. Even though it might take a long time and no small amount of effort to get there, it sure is worth it.

I think that the most effective way to assess (and help improve) our degree of comprehension of a given subject is to try and apply the knowledge to the real world. Not only does this let us identify and ultimately address our weaknesses, but it can also shed some light on the way things work. A simple trial and error approach often reveals those details that had remained elusive previously.

With that in mind, I believe that learning how to implement promises was one of the most important moments in my programming journey — it has given me invaluable insight into how asynchronous code works and has made me a better programmer overall.

I hope that this article will help you come to grips with implementing promises in JavaScript as well.

We shall focus on how to implement the promise core according to the Promises/A+ specification with a few methods of the Bluebird API. We are also going to be using the TDD approach with Jest.

TypeScript is going to come in handy, too.

Given that we are going to be working on the skills of implementation here, I am going to assume you have some basic understanding of what promises are and and a vague sense of how they work. If you don’t, here is a great place to start.

Now that we have that out of the way, go ahead and clone the repository and let’s get started.

The core of a promise

As you know, a promise is an object with the following properties:

Then

A method that attaches a handler to our promise. It returns a new promise with the value from the previous one mapped by one of the handler’s methods.

Handlers

An array of handlers attached by then. A handler is an object containing two methods onSuccess and onFail, both of which are passed as arguments to then(onSuccess, onFail).

type HandlerOnSuccess<T, U = any> = (value: T) => U | Thenable<U>;

type HandlerOnFail<U = any> = (reason: any) => U | Thenable<U>;

interface Handler<T, U> {

onSuccess: HandlerOnSuccess<T, U>;

onFail: HandlerOnFail<U>;

}State

A promise can be in one of three states: resolved, rejected, or pending.

Resolved means that either everything went smoothly and we received our value, or we caught and handled the error.

Rejected means that either we rejected the promise, or an error was thrown and we didn’t catch it.

Pending means that neither the resolve nor the reject method has been called yet and we are still waiting for the value.

The term “the promise is settled” means that the promise is either resolved or rejected.

Value

A value that we have either resolved or rejected.

Once the value is set, there is no way of changing it.

Testing

According to the TDD approach, we want to write our tests before the actual code comes along, so let’s do just that.

Here are the tests for our core:

describe('PQ <constructor>', () => {

test('resolves like a promise', () => {

return new PQ<number>((resolve) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve(1);

}, 30);

}).then((val) => {

expect(val).toBe(1);

});

});

test('is always asynchronous', () => {

const p = new PQ((resolve) => resolve(5));

expect((p as any).value).not.toBe(5);

});

test('resolves with the expected value', () => {

return new PQ<number>((resolve) => resolve(30)).then((val) => {

expect(val).toBe(30);

});

});

test('resolves a thenable before calling then', () => {

return new PQ<number>((resolve) =>

resolve(new PQ((resolve) => resolve(30))),

).then((val) => expect(val).toBe(30));

});

test('catches errors (reject)', () => {

const error = new Error('Hello there');

return new PQ((resolve, reject) => {

return reject(error);

}).catch((err: Error) => {

expect(err).toBe(error);

});

});

test('catches errors (throw)', () => {

const error = new Error('General Kenobi!');

return new PQ(() => {

throw error;

}).catch((err) => {

expect(err).toBe(error);

});

});

test('is not mutable - then returns a new promise', () => {

const start = new PQ<number>((resolve) => resolve(20));

return PQ.all([

start

.then((val) => {

expect(val).toBe(20);

return 30;

})

.then((val) => expect(val).toBe(30)),

start.then((val) => expect(val).toBe(20)),

]);

});

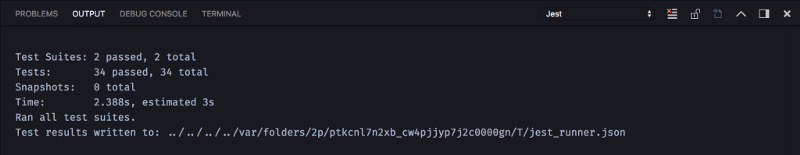

});Running our tests

I highly recommend using the Jest extension for Visual Studio Code. It runs our tests in the background for us and shows us the result right there between the lines of our code as green and red dots for passed and failed tests, respectively.

To see the results, open the “Output” console and choose the “Jest” tab.

We can also run our tests by executing the following command:

npm run testRegardless of how we run the tests, we can see that all of them come back negative.

Let’s change that.

Implementing the Promise core

constructor

class PQ<T> {

private state: States = States.PENDING;

private handlers: Handler<T, any>[] = [];

private value: T | any;

public static errors = errors;

public constructor(callback: (resolve: Resolve<T>, reject: Reject) => void) {

try {

callback(this.resolve, this.reject);

} catch (e) {

this.reject(e);

}

}

}Our constructor takes a callback as a parameter.

We call this callback with this.resolve and this.reject as arguments.

Note that normally we would have bound this.resolve and this.reject to this, but here we have used the class arrow method instead.

setResult

Now we have to set the result. Please remember that we must handle the result correctly, which means that, should it return a promise, we must resolve it first.

class PQ<T> {

// ...

private setResult = (value: T | any, state: States) => {

const set = () => {

if (this.state !== States.PENDING) {

return null;

}

if (isThenable(value)) {

return (value as Thenable<T>).then(this.resolve, this.reject);

}

this.value = value;

this.state = state;

return this.executeHandlers();

};

setTimeout(set, 0);

};

}First, we check if the state is not pending — if it is, then the promise is already settled and we can’t assign any new value to it.

Then we need to check if a value is a thenable. To put it simply, a thenable is an object with then as a method.

By convention, a thenable should behave like a promise. So in order to get the result, we will call then and pass as arguments this.resolve and this.reject.

Once the thenable settles, it will call one of our methods and give us the expected non-promise value.

So now we have to check if an object is a thenable.

describe('isThenable', () => {

test('detects objects with a then method', () => {

expect(isThenable({ then: () => null })).toBe(true);

expect(isThenable(null)).toBe(false);

expect(isThenable({})).toBe(false);

});

});const isFunction = (func: any) => typeof func === 'function';

const isObject = (supposedObject: any) =>

typeof supposedObject === 'object' &&

supposedObject !== null &&

!Array.isArray(supposedObject);

const isThenable = (obj: any) => isObject(obj) && isFunction(obj.then);It is important to realize that our promise will never be synchronous, even if the code inside the callback is.

We are going to delay the execution until the next iteration of the event loop by using setTimeout.

Now the only thing left to do is to set our value and status and then execute the registered handlers.

executeHandlers

class PQ<T> {

// ...

private executeHandlers = () => {

if (this.state === States.PENDING) {

return null;

}

this.handlers.forEach((handler) => {

if (this.state === States.REJECTED) {

return handler.onFail(this.value);

}

return handler.onSuccess(this.value);

});

this.handlers = [];

};

}Again, make sure the state is not pending.

The state of the promise dictates which function we are going to use.

If it’s resolved, we should execute onSuccess, otherwise — onFail.

Let’s now clear our array of handlers just to be safe and not to execute anything accidentally in the future. A handler can be attached and executed later anyways.

And that’s what we must discuss next: a way to attach our handler.

attachHandler

class PQ<T> {

// ...

private attachHandler = (handler: Handler<T, any>) => {

this.handlers = [...this.handlers, handler];

this.executeHandlers();

};

}It really is as simple as it seems. We just add a handler to our handlers array and execute it. That’s it.

Now, to put it all together we need to implement the then method.

then

class PQ<T> {

// ...

public then<U>(

onSuccess?: HandlerOnSuccess<T, U>,

onFail?: HandlerOnFail<U>,

) {

return new PQ<U | T>((resolve, reject) => {

return this.attachHandler({

onSuccess: (result) => {

if (!onSuccess) {

return resolve(result);

}

try {

return resolve(onSuccess(result));

} catch (e) {

return reject(e);

}

},

onFail: (reason) => {

if (!onFail) {

return reject(reason);

}

try {

return resolve(onFail(reason));

} catch (e) {

return reject(e);

}

},

});

});

}

}In then, we return a promise, and in the callback we attach a handler that is then used to wait for the current promise to be settled.

When that happens, either handler’s onSuccess or onFail will be executed and we will proceed accordingly.

One thing to remember here is that neither of the handlers passed to then is required. It is important, however, that we don’t try to execute something that might be undefined.

Also, in onFail when the handler is passed, we actually resolve the returned promise, because the error has been handled.

catch

Catch is actually just an abstraction over the then method.

class PQ<T> {

// ...

public catch<U>(onFail: HandlerOnFail<U>) {

return this.then<U>(identity, onFail);

}

}That’s it.

Finally

Finally is also just an abstraction over doing then(finallyCb, finallyCb), because it doesn’t really care about the result of the promise.

Actually, it also preserves the result of the previous promise and returns it. So whatever is being returned by the finallyCb doesn’t really matter.

describe('PQ.prototype.finally', () => {

test('it is called regardless of the promise state', () => {

let counter = 0;

return PQ.resolve(15)

.finally(() => {

counter += 1;

})

.then(() => {

return PQ.reject(15);

})

.then(() => {

// wont be called

counter = 1000;

})

.finally(() => {

counter += 1;

})

.catch((reason) => {

expect(reason).toBe(15);

expect(counter).toBe(2);

});

});

});class PQ<T> {

// ...

public finally<U>(cb: Finally<U>) {

return new PQ<U>((resolve, reject) => {

let val: U | any;

let isRejected: boolean;

return this.then(

(value) => {

isRejected = false;

val = value;

return cb();

},

(reason) => {

isRejected = true;

val = reason;

return cb();

},

).then(() => {

if (isRejected) {

return reject(val);

}

return resolve(val);

});

});

}

}toString

describe('PQ.prototype.toString', () => {

test('returns [object PQ]', () => {

expect(new PQ<undefined>((resolve) => resolve()).toString()).toBe(

'[object PQ]',

);

});

});class PQ<T> {

// ...

public toString() {

return `[object PQ]`;

}

}It will just return a string [object PQ].

Having implemented the core of our promises, we can now implement some of the previously mentioned Bluebird methods, which will make operating on promises easier for us.

Additional methods

Promise.resolve

describe('PQ.resolve', () => {

test('resolves a value', () => {

return PQ.resolve(5).then((value) => {

expect(value).toBe(5);

});

});

});class PQ<T> {

// ...

public static resolve<U = any>(value?: U | Thenable<U>) {

return new PQ<U>((resolve) => {

return resolve(value);

});

}

}Promise.reject

describe('PQ.reject', () => {

test('rejects a value', () => {

return PQ.reject(5).catch((value) => {

expect(value).toBe(5);

});

});

});class PQ<T> {

// ...

public static reject<U>(reason?: any) {

return new PQ<U>((resolve, reject) => {

return reject(reason);

});

}

}Promise.all

describe('PQ.all', () => {

test('resolves a collection of promises', () => {

return PQ.all([PQ.resolve(1), PQ.resolve(2), 3]).then((collection) => {

expect(collection).toEqual([1, 2, 3]);

});

});

test('rejects if one item rejects', () => {

return PQ.all([PQ.resolve(1), PQ.reject(2)]).catch((reason) => {

expect(reason).toBe(2);

});

});

});class PQ<T> {

// ...

public static all<U = any>(collection: (U | Thenable<U>)[]) {

return new PQ<U[]>((resolve, reject) => {

if (!Array.isArray(collection)) {

return reject(new TypeError('An array must be provided.'));

}

let counter = collection.length;

const resolvedCollection: U[] = [];

const tryResolve = (value: U, index: number) => {

counter -= 1;

resolvedCollection[index] = value;

if (counter !== 0) {

return null;

}

return resolve(resolvedCollection);

};

return collection.forEach((item, index) => {

return PQ.resolve(item)

.then((value) => {

return tryResolve(value, index);

})

.catch(reject);

});

});

}

}I believe the implementation is pretty straightforward.

Starting at collection.length, we count down with each tryResolve until we get to 0, which means that every item of the collection has been resolved. We then resolve the newly created collection.

Promise.any

describe('PQ.any', () => {

test('resolves the first value', () => {

return PQ.any<number>([

PQ.resolve(1),

new PQ((resolve) => setTimeout(resolve, 15)),

]).then((val) => expect(val).toBe(1));

});

test('rejects if the first value rejects', () => {

return PQ.any([

new PQ((resolve) => setTimeout(resolve, 15)),

PQ.reject(1),

]).catch((reason) => {

expect(reason).toBe(1);

});

});

});class PQ<T> {

// ...

public static any<U = any>(collection: (U | Thenable<U>)[]) {

return new PQ<U>((resolve, reject) => {

return collection.forEach((item) => {

return PQ.resolve(item)

.then(resolve)

.catch(reject);

});

});

}

}We simply wait for the first value to resolve and return it in a promise.

Promise.props

describe('PQ.props', () => {

test('resolves object correctly', () => {

return PQ.props<{ test: number; test2: number }>({

test: PQ.resolve(1),

test2: PQ.resolve(2),

}).then((obj) => {

return expect(obj).toEqual({ test: 1, test2: 2 });

});

});

test('rejects non objects', () => {

return PQ.props([]).catch((reason) => {

expect(reason).toBeInstanceOf(TypeError);

});

});

});class PQ<T> {

// ...

public static props<U = any>(obj: object) {

return new PQ<U>((resolve, reject) => {

if (!isObject(obj)) {

return reject(new TypeError('An object must be provided.'));

}

const resolvedObject = {};

const keys = Object.keys(obj);

const resolvedValues = PQ.all<string>(keys.map((key) => obj[key]));

return resolvedValues

.then((collection) => {

return collection.map((value, index) => {

resolvedObject[keys[index]] = value;

});

})

.then(() => resolve(resolvedObject as U))

.catch(reject);

});

}

}We iterate over keys of the passed object, resolving every value. We then assign the values to the new object and resolve a promise with it.

Promise.prototype.spread

describe('PQ.protoype.spread', () => {

test('spreads arguments', () => {

return PQ.all<number>([1, 2, 3]).spread((...args) => {

expect(args).toEqual([1, 2, 3]);

return 5;

});

});

test('accepts normal value (non collection)', () => {

return PQ.resolve(1).spread((one) => {

expect(one).toBe(1);

});

});

});class PQ<T> {

// ...

public spread<U>(handler: (...args: any[]) => U) {

return this.then<U>((collection) => {

if (Array.isArray(collection)) {

return handler(...collection);

}

return handler(collection);

});

}

}Promise.delay

describe('PQ.delay', () => {

test('waits for the given amount of miliseconds before resolving', () => {

return new PQ<string>((resolve) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve('timeout');

}, 50);

return PQ.delay(40).then(() => resolve('delay'));

}).then((val) => {

expect(val).toBe('delay');

});

});

test('waits for the given amount of miliseconds before resolving 2', () => {

return new PQ<string>((resolve) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve('timeout');

}, 50);

return PQ.delay(60).then(() => resolve('delay'));

}).then((val) => {

expect(val).toBe('timeout');

});

});

});class PQ<T> {

// ...

public static delay(timeInMs: number) {

return new PQ((resolve) => {

return setTimeout(resolve, timeInMs);

});

}

}By using setTimeout, we simply delay the execution of the resolve function by the given number of milliseconds.

Promise.prototype.timeout

describe('PQ.prototype.timeout', () => {

test('rejects after given timeout', () => {

return new PQ<number>((resolve) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 50);

})

.timeout(40)

.catch((reason) => {

expect(reason).toBeInstanceOf(PQ.errors.TimeoutError);

});

});

test('resolves before given timeout', () => {

return new PQ<number>((resolve) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve(500), 500);

})

.timeout(600)

.then((value) => {

expect(value).toBe(500);

});

});

});class PQ<T> {

// ...

public timeout(timeInMs: number) {

return new PQ<T>((resolve, reject) => {

const timeoutCb = () => {

return reject(new PQ.errors.TimeoutError());

};

setTimeout(timeoutCb, timeInMs);

return this.then(resolve);

});

}

}This one is a bit tricky.

If the setTimeout executes faster than then in our promise, it will reject the promise with our special error.

Promise.promisify

describe('PQ.promisify', () => {

test('works', () => {

const getName = (firstName, lastName, callback) => {

return callback(null, `${firstName} ${lastName}`);

};

const fn = PQ.promisify<string>(getName);

const firstName = 'Maciej';

const lastName = 'Cieslar';

return fn(firstName, lastName).then((value) => {

return expect(value).toBe(`${firstName} ${lastName}`);

});

});

});class PQ<T> {

// ...

public static promisify<U = any>(

fn: (...args: any[]) => void,

context = null,

) {

return (...args: any[]) => {

return new PQ<U>((resolve, reject) => {

return fn.apply(context, [

...args,

(err: any, result: U) => {

if (err) {

return reject(err);

}

return resolve(result);

},

]);

});

};

}

}We apply to the function all the passed arguments, plus — as the last one — we give the error-first callback.

Promise.promisifyAll

describe('PQ.promisifyAll', () => {

test('promisifies a object', () => {

const person = {

name: 'Maciej Cieslar',

getName(callback) {

return callback(null, this.name);

},

};

const promisifiedPerson = PQ.promisifyAll<{

getNameAsync: () => PQ<string>;

}>(person);

return promisifiedPerson.getNameAsync().then((name) => {

expect(name).toBe('Maciej Cieslar');

});

});

});class PQ<T> {

// ...

public static promisifyAll<U>(obj: any): U {

return Object.keys(obj).reduce((result, key) => {

let prop = obj[key];

if (isFunction(prop)) {

prop = PQ.promisify(prop, obj);

}

result[`${key}Async`] = prop;

return result;

}, {}) as U;

}

}We iterate over the keys of the object and promisify its methods and add to each name of the method word Async.

Wrapping up

Presented here were but a few amongst all of the Bluebird API methods, so I strongly encourage you to explore, play around with, and try implementing the rest of them.

It might seem hard at first but don’t get discouraged — it would be worthless if it were it easy.

Thank you very much for reading! I hope you found this article informative and that it helped you get a grasp of the concept of promises, and that from now on you will feel more comfortable using them or simply writing asynchronous code.

If you have any questions or comments, feel free to put them in the comment section below or send me a message.

Check out my social media!

Originally published at www.mcieslar.com on August 4, 2018.