by Sergey Kamardin

A Million WebSockets and Go

Hi everyone! My name is Sergey Kamardin and I’m a developer at Mail.Ru.

This article is about how we developed the high-load WebSocket server with Go.

If you are familiar with WebSockets, but know little about Go, I hope you will still find this article interesting in terms of ideas and techniques for performance optimization.

1. Introduction

To define the context of our story, a few words should be said about why we need this server.

Mail.Ru has a lot of stateful systems. User email storage is one of them. There are several ways to keep track of state changes within a system— and about the system events. Mostly this is either through periodic system polling or system notifications about its state changes.

Both ways have their pros and cons. But when it comes to mail, the faster a user receives new mail, the better.

Mail polling involves about 50,000 HTTP queries per second, 60% of which return the 304 status, meaning there are no changes in the mailbox.

Therefore, in order to reduce the load on the servers and to speed up mail delivery to users, the decision was made to re-invent the wheel by writing a publisher-subscriber server (also known as a bus, message broker, or event-channel) that would receive notifications about state changes on the one hand, and subscriptions for such notifications on the other.

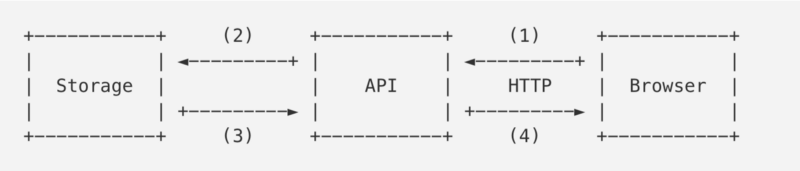

Previously:

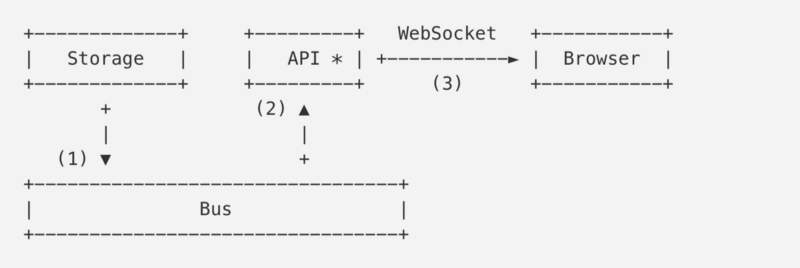

Now:

The first scheme shows what it was like before. The browser periodically polled the API and asked about Storage (mailbox service) changes.

The second scheme describes the new architecture. The browser establishes a WebSocket connection with the notification API, which is a client to the Bus server. Upon receipt of new email, Storage sends a notification about it to Bus (1), and Bus to its subscribers (2). The API determines the connection to send the received notification, and sends it to the user’s browser (3).

So today we’re going to talk about the API or the WebSocket server. Looking ahead, I’ll tell you that the server will have about 3 million online connections.

2. The idiomatic way

Let’s see how we would implement certain parts of our server using plain Go features without any optimizations.

Before we proceed with net/http, let's talk about how we will send and receive data. The data which stands above the WebSocket protocol (e.g. JSON objects) will hereinafter be referred to as packets.

Let's begin implementing the Channel structure that will contain the logic of sending and receiving such packets over the WebSocket connection.

2.1. Channel struct

// Packet represents application level data.

type Packet struct {

...

}

// Channel wraps user connection.

type Channel struct {

conn net.Conn // WebSocket connection.

send chan Packet // Outgoing packets queue.

}

func NewChannel(conn net.Conn) *Channel {

c := &Channel{

conn: conn,

send: make(chan Packet, N),

}

go c.reader()

go c.writer()

return c

}I’d like to draw your attention to the launch of two reading and writing goroutines. Each goroutine requires its own memory stack that may have an initial size of 2 to 8 KB depending on the operating system and Go version.

Regarding the above mentioned number of 3 million online connections, we will need 24 GB of memory (with the stack of 4 KB) for all connections. And that’s without the memory allocated for the Channel structure, the outgoing packets ch.send and other internal fields.

2.2. I/O goroutines

Let’s have a look at the implementation of the “reader”:

func (c *Channel) reader() {

// We make a buffered read to reduce read syscalls.

buf := bufio.NewReader(c.conn)

for {

pkt, _ := readPacket(buf)

c.handle(pkt)

}

}Here we use the bufio.Reader to reduce the number of read() syscalls and to read as many as allowed by the buf buffer size. Within the infinite loop, we expect new data to come. Please remember the words: expect new data to come. We will return to them later.

We will leave aside the parsing and processing of incoming packets, as it is not important for the optimizations we will talk about. However, buf is worth our attention now: by default, it is 4 KB which means another 12 GB of memory for our connections. There is a similar situation with the "writer":

func (c *Channel) writer() {

// We make buffered write to reduce write syscalls.

buf := bufio.NewWriter(c.conn)

for pkt := range c.send {

_ := writePacket(buf, pkt)

buf.Flush()

}

}We iterate across the outgoing packets channel c.send and write them to the buffer. This is, as our attentive readers can already guess, another 4 KB and 12 GB of memory for our 3 million connections.

2.3. HTTP

We already have a simple Channel implementation, now we need to get a WebSocket connection to work with. As we are still under the Idiomatic Way heading, let's do it in the corresponding way.

Note: If you don’t know how WebSocket works, it should be mentioned that the client switches to the WebSocket protocol by means of a special HTTP mechanism called Upgrade. After the successful processing of an Upgrade request, the server and the client use the TCP connection to exchange binary WebSocket frames. Here is a description of the frame structure inside the connection.

import (

"net/http"

"some/websocket"

)

http.HandleFunc("/v1/ws", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

conn, _ := websocket.Upgrade(r, w)

ch := NewChannel(conn)

//...

})Please note that http.ResponseWriter makes memory allocation for bufio.Reader and bufio.Writer (both with 4 KB buffer) for *http.Request initialization and further response writing.

Regardless of the WebSocket library used, after a successful response to the Upgrade request, the server receives I/O buffers together with the TCP connection after the responseWriter.Hijack() call.

Hint: in some cases thego:linknamecan be used to return the buffers to thesync.Poolinsidenet/httpthrough the callnet/http.putBufio{Reader,Writer}.

Thus, we need another 24 GB of memory for 3 million connections.

So, a total of 72 GB of memory for the application that does nothing yet!

3. Optimizations

Let’s review what we talked about in the introduction part and remember how a user connection behaves. After switching to WebSocket, the client sends a packet with the relevant events or in other words subscribes for events. Then (not taking into account technical messages such as ping/pong), the client may send nothing else for the whole connection lifetime.

The connection lifetime may last from several seconds to several days.

So for the most time our Channel.reader() and Channel.writer() are waiting for the handling of data for receiving or sending. Along with them waiting are the I/O buffers of 4 KB each.

Now it is clear that certain things could be done better, couldn’t they?

3.1. Netpoll

Do you remember the Channel.reader() implementation that expected new data to come by getting locked on the conn.Read() call inside the bufio.Reader.Read()? If there was data in the connection, Go runtime "woke up" our goroutine and allowed it to read the next packet. After that, the goroutine got locked again while expecting new data. Let's see how Go runtime understands that the goroutine must be "woken up".

If we look at the conn.Read() implementation, we’ll see the net.netFD.Read() call inside it:

// net/fd_unix.go

func (fd *netFD) Read(p []byte) (n int, err error) {

//...

for {

n, err = syscall.Read(fd.sysfd, p)

if err != nil {

n = 0

if err == syscall.EAGAIN {

if err = fd.pd.waitRead(); err == nil {

continue

}

}

}

//...

break

}

//...

}Go uses sockets in non-blocking mode. EAGAIN says there is no data in the socket and not to get locked on reading from the empty socket, OS returns control to us.

We see a read() syscall from the connection file descriptor. If read returns the EAGAIN error, runtime makes the pollDesc.waitRead() call:

// net/fd_poll_runtime.go

func (pd *pollDesc) waitRead() error {

return pd.wait('r')

}

func (pd *pollDesc) wait(mode int) error {

res := runtime_pollWait(pd.runtimeCtx, mode)

//...

}If we dig deeper, we’ll see that netpoll is implemented using epoll in Linux and kqueue in BSD. Why not use the same approach for our connections? We could allocate a read buffer and start the reading goroutine only when it is really necessary: when there is really readable data in the socket.

On github.com/golang/go, there is the issue of exporting netpoll functions.

3.2. Getting rid of goroutines

Suppose we have netpoll implementation for Go. Now we can avoid starting the Channel.reader() goroutine with the inside buffer, and subscribe for the event of readable data in the connection:

ch := NewChannel(conn)

// Make conn to be observed by netpoll instance.

poller.Start(conn, netpoll.EventRead, func() {

// We spawn goroutine here to prevent poller wait loop

// to become locked during receiving packet from ch.

go Receive(ch)

})

// Receive reads a packet from conn and handles it somehow.

func (ch *Channel) Receive() {

buf := bufio.NewReader(ch.conn)

pkt := readPacket(buf)

c.handle(pkt)

}It is easier with the Channel.writer() because we can run the goroutine and allocate the buffer only when we are going to send the packet:

func (ch *Channel) Send(p Packet) {

if c.noWriterYet() {

go ch.writer()

}

ch.send <- p

}Note that we do not handle cases when operating system returnsEAGAINonwrite()system calls. We lean on Go runtime for such cases, cause it is actually rare for such kind of servers. Nevertheless, it could be handled in the same way if needed.

After reading the outgoing packets from ch.send (one or several), the writer will finish its operation and free the goroutine stack and the send buffer.

Perfect! We have saved 48 GB by getting rid of the stack and I/O buffers inside of two continuously running goroutines.

3.3. Control of resources

A great number of connections involves not only high memory consumption. When developing the server, we experienced repeated race conditions and deadlocks often followed by the so-called self-DDoS — a situation when the application clients rampantly tried to connect to the server thus breaking it even more.

For example, if for some reason we suddenly could not handle ping/pong messages, but the handler of idle connections continued to close such connections (supposing that the connections were broken and therefore provided no data), the client appeared to lose connection every N seconds and tried to connect again instead of waiting for events.

It would be great if the locked or overloaded server just stopped accepting new connections, and the balancer before it (for example, nginx) passed request to the next server instance.

Moreover, regardless of the server load, if all clients suddenly want to send us a packet for any reason (presumably by cause of bug), the previously saved 48 GB will be of use again, as we will actually get back to the initial state of the goroutine and the buffer per each connection.

Goroutine pool

We can restrict the number of packets handled simultaneously using a goroutine pool. This is what a naive implementation of such pool looks like:

package gopool

func New(size int) *Pool {

return &Pool{

work: make(chan func()),

sem: make(chan struct{}, size),

}

}

func (p *Pool) Schedule(task func()) error {

select {

case p.work <- task:

case p.sem <- struct{}{}:

go p.worker(task)

}

}

func (p *Pool) worker(task func()) {

defer func() { <-p.sem }

for {

task()

task = <-p.work

}

}Now our code with netpoll looks as follows:

pool := gopool.New(128)

poller.Start(conn, netpoll.EventRead, func() {

// We will block poller wait loop when

// all pool workers are busy.

pool.Schedule(func() {

Receive(ch)

})

})So now we read the packet not only upon readable data appearance in the socket, but also upon the first opportunity to take up the free goroutine in the pool.

Similarly, we’ll change Send():

pool := gopool.New(128)

func (ch *Channel) Send(p Packet) {

if c.noWriterYet() {

pool.Schedule(ch.writer)

}

ch.send <- p

}Instead of go ch.writer(), we want to write in one of the reused goroutines. Thus, for a pool of N goroutines, we can guarantee that with N requests handled simultaneously and the arrived N + 1 we will not allocate a N + 1 buffer for reading. The goroutine pool also allows us to limit Accept() and Upgrade() of new connections and to avoid most situations with DDoS.

3.4. Zero-copy upgrade

Let’s deviate a little from the WebSocket protocol. As was already mentioned, the client switches to the WebSocket protocol using a HTTP Upgrade request. This is what it looks like:

GET /ws HTTP/1.1

Host: mail.ru

Connection: Upgrade

Sec-Websocket-Key: A3xNe7sEB9HixkmBhVrYaA==

Sec-Websocket-Version: 13

Upgrade: websocket

HTTP/1.1 101 Switching Protocols

Connection: Upgrade

Sec-Websocket-Accept: ksu0wXWG+YmkVx+KQR2agP0cQn4=

Upgrade: websocketThat is, in our case we need the HTTP request and its headers only for switch to the WebSocket protocol. This knowledge and what is stored inside the http.Request suggests that for the sake of optimization, we could probably refuse unnecessary allocations and copyings when processing HTTP requests and abandon the standard net/http server.

For example, the http.Request contains a field with the same-name Header type that is unconditionally filled with all request headers by copying data from the connection to the values strings. Imagine how much extra data could be kept inside this field, for example for a large-size Cookie header.But what to take in return?

WebSocket implementation

Unfortunately, all libraries existing at the time of our server optimization allowed us to do upgrade only for the standard net/http server. Moreover, neither of the (two) libraries made it possible to use all the above read and write optimizations. For these optimizations to work, we must have a rather low-level API for working with WebSocket. To reuse the buffers, we need the procotol functions to look like this:

func ReadFrame(io.Reader) (Frame, error)

func WriteFrame(io.Writer, Frame) errorIf we had a library with such API, we could read packets from the connection as follows (the packet writing would look the same):

// getReadBuf, putReadBuf are intended to

// reuse *bufio.Reader (with sync.Pool for example).

func getReadBuf(io.Reader) *bufio.Reader

func putReadBuf(*bufio.Reader)

// readPacket must be called when data could be read from conn.

func readPacket(conn io.Reader) error {

buf := getReadBuf()

defer putReadBuf(buf)

buf.Reset(conn)

frame, _ := ReadFrame(buf)

parsePacket(frame.Payload)

//...

}In short, it was time to make our own library.

github.com/gobwas/ws

Ideologically, the ws library was written so as not to impose its protocol operation logic on users. All reading and writing methods accept standard io.Reader and io.Writer interfaces, which makes it possible to use or not to use buffering or any other I/O wrappers.

Besides upgrade requests from standard net/http, ws supports zero-copy upgrade, the handling of upgrade requests and switching to WebSocket without memory allocations or copyings. ws.Upgrade() accepts io.ReadWriter (net.Conn implements this interface). In other words, we could use the standard net.Listen() and transfer the received connection from ln.Accept() immediately to ws.Upgrade(). The library makes it possible to copy any request data for future use in the application (for example, Cookie to verify the session).

Below there are benchmarks of Upgrade request processing: standard net/http server versus net.Listen() with zero-copy upgrade:

BenchmarkUpgradeHTTP 5156 ns/op 8576 B/op 9 allocs/op

BenchmarkUpgradeTCP 973 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/opSwitching to ws and zero-copy upgrade saved us another 24 GB — the space allocated for I/O buffers upon request processing by the net/http handler.

3.5. Summary

Let’s structure the optimizations I told you about.

- A read goroutine with a buffer inside is expensive. Solution: netpoll (epoll, kqueue); reuse the buffers.

- A write goroutine with a buffer inside is expensive. Solution: start the goroutine when necessary; reuse the buffers.

- With a storm of connections, netpoll won’t work. Solution: reuse the goroutines with the limit on their number.

net/httpis not the fastest way to handle Upgrade to WebSocket. Solution: use the zero-copy upgrade on bare TCP connection.

That is what the server code could look like:

import (

"net"

"github.com/gobwas/ws"

)

ln, _ := net.Listen("tcp", ":8080")

for {

// Try to accept incoming connection inside free pool worker.

// If there no free workers for 1ms, do not accept anything and try later.

// This will help us to prevent many self-ddos or out of resource limit cases.

err := pool.ScheduleTimeout(time.Millisecond, func() {

conn := ln.Accept()

_ = ws.Upgrade(conn)

// Wrap WebSocket connection with our Channel struct.

// This will help us to handle/send our app's packets.

ch := NewChannel(conn)

// Wait for incoming bytes from connection.

poller.Start(conn, netpoll.EventRead, func() {

// Do not cross the resource limits.

pool.Schedule(func() {

// Read and handle incoming packet(s).

ch.Recevie()

})

})

})

if err != nil {

time.Sleep(time.Millisecond)

}

}4. Conclusion

Premature optimization is the root of all evil (or at least most of it) in programming. Donald Knuth

Of course, the above optimizations are relevant, but not in all cases. For example if the ratio between free resources (memory, CPU) and the number of online connections is rather high, there is probably no sense in optimizing. However, you can benefit a lot from knowing where and what to improve.

Thank you for your attention!