by Pablo Regen

You’ve probably read these sentences before…

Node.js is a JavaScript runtime built on Chrome’s V8 JavaScript engine

Node.js uses an event-driven, asynchronous non-blocking I/O model

Node.js operates on a single thread event loop

… and were left wondering what all this meant. Hopefully by the end of this article you’ll have a better understanding about these terms as well as about what Node is, how it works, and why and when is a good idea to use it.

Let’s start by going over the terminology.

I/O (input/output)

Short for input/output, I/O refers primarily to the program’s interaction with the system’s disk and network. Examples of I/O operations include reading/writing data from/to a disk, making HTTP requests, and talking to databases. They are very slow compared to accessing memory (RAM) or doing work on the CPU.

Synchronous vs Asynchronous

Synchronous (or sync) execution usually refers to code executing in sequence. In sync programming, the program is executed line by line, one line at a time. Each time a function is called, the program execution waits until that function returns before continuing to the next line of code.

Asynchronous (or async) execution refers to execution that doesn’t run in the sequence it appears in the code. In async programming the program doesn’t wait for the task to complete and can move on to the next task.

In the following example, the sync operation causes the alerts to fire in sequence. In the async operation, while alert(2) appears to execute second, it doesn’t.

// Synchronous: 1,2,3

alert(1);

alert(2);

alert(3);

// Asynchronous: 1,3,2

alert(1);

setTimeout(() => alert(2), 0);

alert(3);An async operation is often I/O related, although setTimeout is an example of something that isn’t I/O but still async. Generally speaking, anything computation-related is sync and anything input/output/timing-related is async. The reason for I/O operations to be done asynchronously is that they are very slow and would block further execution of code otherwise.

Blocking vs Non-blocking

Blocking refers to operations that block further execution until that operation finishes while non-blocking refers to code that doesn’t block execution. Or as Node.js docs puts it, blocking is when the execution of additional JavaScript in the Node.js process must wait until a non-JavaScript operation completes.

Blocking methods execute synchronously while non-blocking methods execute asynchronously.

// Blocking

const fs = require('fs');

const data = fs.readFileSync('/file.md'); // blocks here until file is read

console.log(data);

moreWork(); // will run after console.log

// Non-blocking

const fs = require('fs');

fs.readFile('/file.md', (err, data) => {

if (err) throw err;

console.log(data);

});

moreWork(); // will run before console.logIn the first example above, console.log will be called before moreWork(). In the second example fs.readFile() is non-blocking so JavaScript execution can continue and moreWork() will be called first.

In Node, non-blocking primarily refers to I/O operations, and JavaScript that exhibits poor performance due to being CPU intensive rather than waiting on a non-JavaScript operation, such as I/O, isn’t typically referred to as blocking.

All of the I/O methods in the Node.js standard library provide async versions, which are non-blocking, and accept callback functions. Some methods also have blocking counterparts, which have names that end with Sync.

Non-blocking I/O operations allow a single process to serve multiple requests at the same time. Instead of the process being blocked and waiting for I/O operations to complete, the I/O operations are delegated to the system, so that the process can execute the next piece of code. Non-blocking I/O operations provide a callback function that is called when the operation is completed.

Callbacks

A callback is a function passed as an argument into another function, which can then be invoked (called back) inside the outer function to complete some kind of action at a convenient time. The invocation may be immediate (sync callback) or it might happen at a later time (async callback).

// Sync callback

function greetings(callback) {

callback();

}

greetings(() => { console.log('Hi'); });

moreWork(); // will run after console.log

// Async callback

const fs = require('fs');

fs.readFile('/file.md', function callback(err, data) { // fs.readFile is an async method provided by Node

if (err) throw err;

console.log(data);

});

moreWork(); // will run before console.log

In the first example, the callback function is called immediately within the outer greetings function and logs to the console before moreWork() proceeds.

In the second example, fs.readFile (an async method provided by Node) reads the file and when it finishes it calls the callback function with an error or the file content. In the meantime the program can continue code execution.

An async callback may be called when an event happens or when a task completes. It prevents blocking by allowing other code to be executed in the meantime.

Instead of the code reading top to bottom procedurally, async programs may execute different functions at different times based on the order and speed that earlier functions like http requests or file system reads happen. They are used when you don’t know when some async operation will complete.

You should avoid “callback hell”, a situation where callbacks are nested within other callbacks several levels deep, making the code difficult to understand, maintain and debug.

Events and event-driven programming

Events are actions generated by the user or the system, like a click, a completed file download, or a hardware or software error.

Event-driven programming is a programming paradigm in which the flow of the program is determined by events. An event-driven program performs actions in response to events. When an event occurs it triggers a callback function.

Now, let’s try to understand Node and see how all these relate to it.

Node.js: what is it, why was it created, and how does it work?

Simply put, Node.js is a platform that executes server-side JavaScript programs that can communicate with I/O sources like networks and file systems.

When Ryan Dahl created Node in 2009 he argued that I/O was being handled incorrectly, blocking the entire process due to synchronous programming.

Traditional web-serving techniques use the thread model, meaning one thread for each request. Since in an I/O operation the request spends most of the time waiting for it to complete, intensive I/O scenarios entail a large amount of unused resources (such as memory) linked to these threads. Therefore the “one thread per request” model for a server doesn’t scale well.

Dahl argued that software should be able to multi-task and proposed eliminating the time spent waiting for I/O results to come back. Instead of the thread model, he said the right way to handle several concurrent connections was to have a single-thread, an event loop and non-blocking I/Os. For example, when you make a query to a database, instead of waiting for the response you give it a callback so your execution can run through that statement and continue doing other things. When the results come back you can execute the callback.

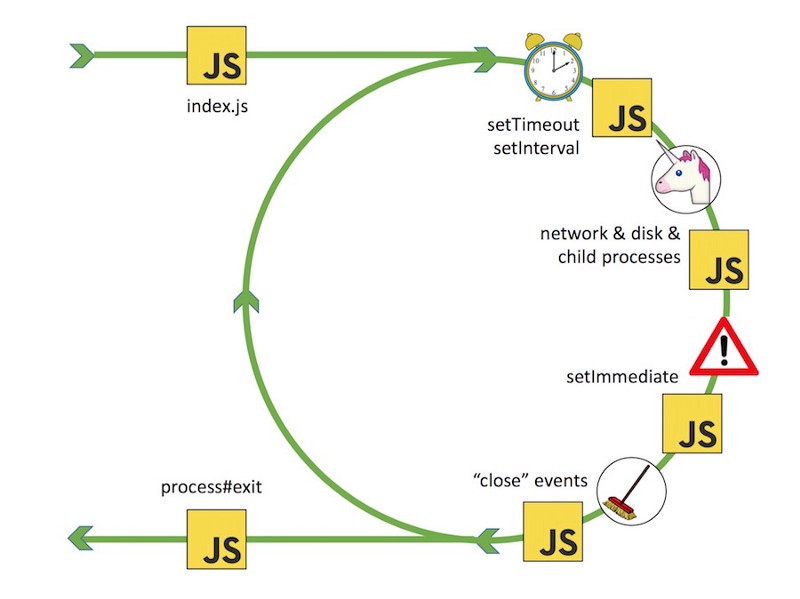

The event loop is what allows Node.js to perform non-blocking I/O operations despite the fact that JavaScript is single-threaded. The loop, which runs on the same thread as the JavaScript code, grabs a task from the code and executes it. If the task is async or an I/O operation the loop offloads it to the system kernel, like in the case for new connections to the server, or to a thread pool, like file system related operations. The loop then grabs the next task and executes it.

Since most modern kernels are multi-threaded, they can handle multiple operations executing in the background. When one of these operations completes (this is an event), the kernel tells Node.js so that the appropriate callback (the one that depended on the operation completing) may be added to the poll queue to eventually be executed.

Node keeps track of unfinished async operations, and the event loop keeps looping to check if they are finished until all of them are.

To accommodate the single-threaded event loop, Node.js uses the libuv library, which, in turn, uses a fixed-sized thread pool that handles the execution of some of the non-blocking asynchronous I/O operations in parallel. The main thread call functions post tasks to the shared task queue, which threads in the thread pool pull and execute.

Inherently non-blocking system functions such as networking translate to kernel-side non-blocking sockets, while inherently blocking system functions such as file I/O run in a blocking way on their own threads. When a thread in the thread pool completes a task, it informs the main thread of this, which in turn, wakes up and executes the registered callback.

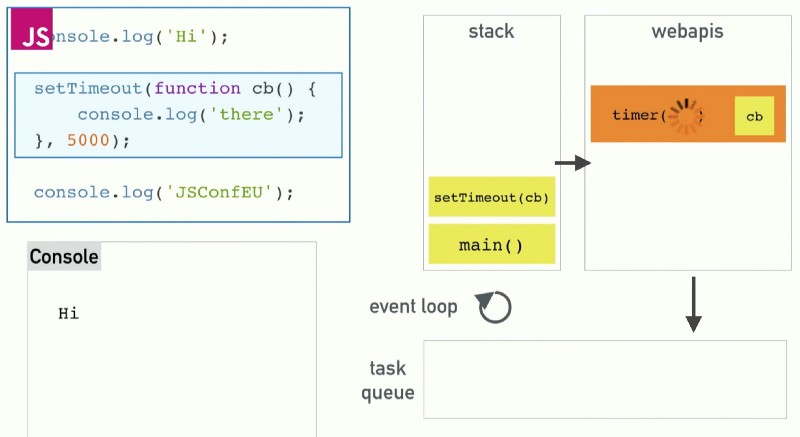

The above image is taken from Philip Roberts’ presentation at JSConf EU: What the heck is the event loop anyway? I recommend watching the full video to get a high level idea about how the event loop works.

The diagram explains how the event loop works with the browser but it looks basically identical for Node. Instead of web APIs we would have Node APIs.

According to the presentation, the call stack (aka execution stack or “the stack”) is a data structure which records where in the program we are. If we step into a function, we put something onto the stack. If we return from a function, we pop it off the top of the stack.

This is how the code in the diagram is processed when we run it:

- Push

main()onto the stack (the file itself) - Push

console.log(‘Hi’);onto the stack, which executes immediately logging “Hi” to the console and gets popped off the stack - Push

setTimeout(cb, 5000)onto the stack. setTimeout is an API provided by the browser (on the backend it would be a Node API). When setTimeout is called with the callback function and delay arguments, the browser kicks off a timer with the delay time - The

setTimeoutcall is completed and gets popped off the stack - Push

console.log(‘JSConfEU’);onto the stack, which executes immediately logging “JSConfEU” to the console and gets popped off the stack main()gets popped off the stack- After 5000 milliseconds the API timer completes and the callback gets moved to the task queue

- The event loop checks if the stack is empty because JavaScript, being single-threaded, can only do one thing at a time (setTimeout is not a guaranteed but a minimum time to execution). If the stack is empty it takes the first thing on the queue and pushes it onto the stack. Therefore the loop pushes the callback onto the stack

- The callback gets executed, logs “there” to the console and gets popped off the stack. And we are done

If you want to go even deeper into the details on how Node.js, libuv, the event loop and the thread pool work, I suggest checking the resources on the reference section at the end, in particular this, this and this along with the Node docs.

Node.js: why and where to use it?

Since almost no function in Node directly performs I/O, the process never blocks (I/O operations are offloaded and executed asynchronously in the system), making it a good choice to develop highly scalable systems.

Due to its event-driven, single-threaded event loop and asynchronous non-blocking I/O model, Node.js performs best on intense I/O applications requiring speed and scalability with lots of concurrent connections, like video & audio streaming, real-time apps, live chats, gaming apps, collaboration tools, or stock exchange software.

Node.js may not be the right choice for CPU intensive operations. Instead the traditional thread model may perform better.

npm

npm is the default package manager for Node.js and it gets installed into the system when Node.js is installed. It can manage packages that are local dependencies of a particular project, as well as globally-installed JavaScript tools.

www.npmjs.com hosts thousands of free libraries to download and use in your program to make development faster and more efficient. However, since anybody can create libraries and there’s no vetting process for submission, you have to be careful about low quality, insecure, or malicious ones. npm relies on user reports to take down packages if they violate policies, and to help you decide, it includes statistics like number of downloads and number of depending packages.

How to run code in Node.js

Start by installing Node on your computer if you don’t have it already. The easiest way is to visit nodejs.org and click to download it. Unless you want or need to have access to the latest features, download the LTS (Long Term Support) version for you operating system.

You run a Node application from your computer’s terminal. For example make a file “app.js” and add console.log(‘Hi’); to it. On your terminal change the directory to the folder where this file belongs to and run node app.js. It will log “Hi” to the console. ?

References

Here are some of the interesting resources I reviewed during the writing of the article.

Node.js presentations by its author:

- Original Node.js presentation by Ryan Dahl at JSConf 2009

- 10 Things I Regret About Node.js by Ryan Dahl at JSConf EU 2018

Node, the event loop and the libuv library presentations:

- What the heck is the event loop anyway? by Philip Roberts at JSConf EU

- Node.js Explained by Jeff Kunkle

- In The Loop by Jake Archibald at JSConf Asia 2018

- Everything You Need to Know About Node.js Event Loop by Bert Belder

- A deep dive into libuv by Saul Ibarra Coretge at NodeConf EU 2016

Node documents:

- About Node.js

- The Node.js Event Loop, Timers, and process.nextTick()

- Overview of Blocking vs Non-Blocking

Additional resources:

- Art of Node by Max Ogden

- Callback hell by Max Ogden

- What is non-blocking or asynchronous I/O in Node.js? on Stack Overflow

- Event driven programming on Wikipedia

- Node.js on Wikipedia

- Thread on Wikipedia

- libuv

Thanks for reading.