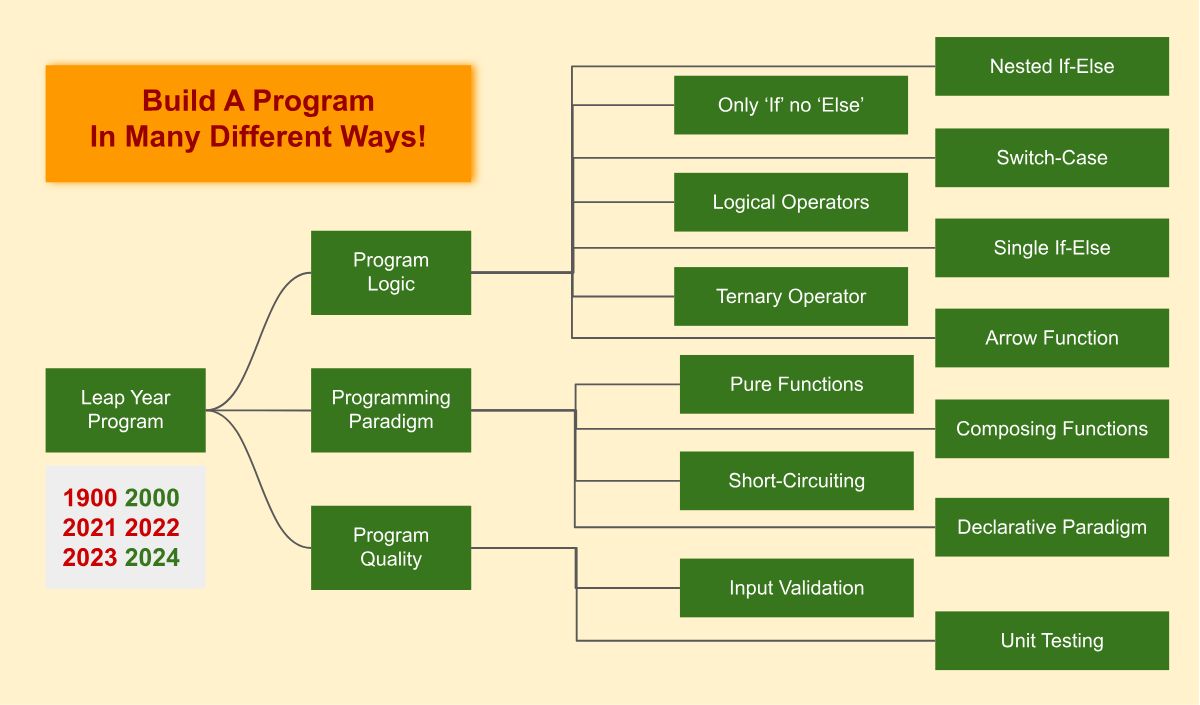

While we have 365 days in other years, this year (2024) is special because it has one ‘extra’ day.

So in the spirit of Leap Day, let's practice some coding to understand various aspects of programming. We'll focus on the same program but from different perspectives.

Our example program will explore different ways you can code a program that determines whether a given year is a leap year. On other days, we code. But today, let’s decode what we do and get some extra knowledge out of that process.

Table of Contents

- Program Requirements & Prerequisites

- Logical Approaches to Solving the Problem

- My Naïve Approach

- Reassignments and a Single Return Statement

- Switching to Switch-Case from If-Else

- Logical Deduction & Subsets for Better Structure

- Logical Operators Combining All True Conditions

- Applying Nitro with the Ternary Operator

- Making it a Single Line Arrow Function

- Paradigm Shift: Declarative Programming

- Functions with Side Effects

- More About Functional Programming

- Side-Tracking: Short-Circuiting!

- Encapsulation and Declarative Programming

- Going Above & Beyond with Code Quality

- End Note

Program Requirements & Prerequisites

First, let’s discuss the requirements and set the specifications. The program should be able to get a year (expects a number, an integer to be specific) as an argument and returns either true or false (a boolean) depending on if it is a leap year or not.

Through the examples, we will focus on the program logic (semantics) rather than the language (syntax).

Over the years, I have used JavaScript most frequently so we'll use this language for the project. If you use a different language, no worries because many concepts are common between programming languages. For example, in this article, we would use arrow function which is similar to lambda function used in some other programming languages, such as Python.

So, as prerequisites, you should have a basic knowledge of programming and should be comfortable with the concepts of functions (different ways to define and call functions, return values, and so on) and conditional logic (if-else, switch-case, and so on). That would be enough to follow along, for the most part, if you want to read and try the code for yourself.

Just in the last bit, we also do unit testing of our code. If you aren't familiar with unit testing, here is a good refresher on how to write unit tests in JavaScript with Jest.

Logical Approaches to Solving the Problem

My Naïve Approach

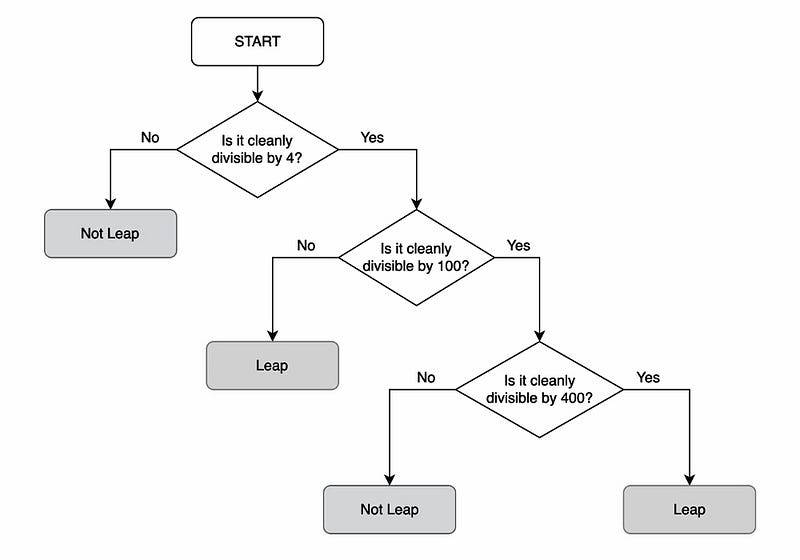

This is based on the pedagogical style of determining a leap year that I learned as a kid who knew how to divide numbers. If a year ( the number representing it) is divisible by 4, it is generally a leap year. But not always. When that year ends with two zeroes (meaning when the number is divisible by 100), it must also be divisible by 400 to be a leap year.

As a beginner programmer, my thoughts flowed like you can see in the above flowchart. As a result, I converted that logic into my program like so:

function isLeapYear(year) {

if (year % 4 == 0) {

if (year % 100 == 0) {

if (year % 400 == 0) {

return true;

} else {

return false;

}

} else {

return true;

}

} else {

return false

}

}

// Example usage:

console.log(isLeapYear(2024)); // Output: true

console.log(isLeapYear(2023)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(1900)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(2000)); // Output: true

This makes the program easily understandable. But with time, as I have moved farther in my programming journey, this type of code looks ugly because of so many nested conditional checks. It's not bad, but because of the nested levels, my brain has to work extra hard to get the logic from the code snapshot quickly.

Reassignments and a Single Return Statement

To avoid nested loops, many programmers follow the strategy of consecutive if conditions, avoiding the else conditions (like how Kyle Cook of Web Dev Simplified shows in this video with examples). It definitely improves readability.

Also, it lets us use only one return statement at the end while reassigning the returnable value. Let's not discuss it too much more when you can better see the code itself:

function isLeapYear(year) {

let isLeap = false;

if (year % 4 == 0) {

isLeap = true;

}

if (year % 100 == 0) {

isLeap = false;

}

if (year % 400 == 0) {

isLeap = true;

}

return isLeap;

}

// Example usage:

console.log(isLeapYear(2024)); // Output: true

console.log(isLeapYear(2023)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(1900)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(2000)); // Output: true

The above code looks shorter and quicker to interpret. But it does affect the efficiency of the code, as now you have to go through all of the if conditions in all cases.

In contrast, in our previous naïve approach, due to the if-else construct, if a year is not divisible by 4 (like the year 2023), it would just be checked against one if condition. It’s true, of course, that for small programs such as this one, you don’t have to be overly concerned with efficiency.

The pitfall in this approach, though, is that you need to be cautious to apply all the if conditions one after another — using ‘else if’ would create trouble, as that would skip some if condition checks if the previous if condition test passed.

Another important fact is that the order matters. Since you started with the more generic cases of years not being a leap year (that is, let isLeap = false;), you have to go from relatively generic to relatively more specific cases.

So if, out of your three condition checks, the check of divisibility by 4 comes at the end, it would make ‘isLeap’ true even for years that are divisible by 100 but not divisible by 400 (like years 1700, 1800, 1900, and so on).

The same logical error would occur if you interchange the order of divisibility checks involving 100 and 400.

One last point I must mention is that some beginner programmers may think that you can not use multiple return statements and you must return only once in a program (and that you can do reassignments until that point). But experienced programmers can only call that notion a beginners’ myth!

Switching to Switch-Case from If-Else

While the if-else structure is used to choose between two options, you can also use switch-case to choose one from multiple options. You can compare it to nested if-else blocks (as in the first approach) or a series of if blocks (as in the second approach).

The benefit of the switch-case structure is that it is more efficient because it can find the matching success criteria in one go.

Note that there is one quirky thing with switch-case. When using switch-case, once a case is matched, all subsequent cases will also execute unless you are using break statements. So, the following program will not be correct even if it looks very similar to our previous version of the code.

**Incorrect code: to show problems with missing break statements **

function isLeapYear(year) {

let isLeap = false;

switch (true) {

case year % 4 == 0:

isLeap = true;

case year % 100 == 0:

isLeap = false;

case year % 400 == 0:

isLeap = true;

}

return isLeap;

}

If we must use a switch-case structure, we need to use break statements. We also need to go from specific cases first to generic cases next. While not all if-else logic can be converted into a switch-case logic, we can successfully convert the previous function like so:

function isLeapYear(year) {

let isLeap = false;

switch (true) {

case year % 400 == 0:

isLeap = true;

break;

case year % 100 == 0:

isLeap = false;

break;

case year % 4 == 0:

isLeap = true;

break;

}

return isLeap;

}

// Example usage:

console.log(isLeapYear(2024)); // Output: true

console.log(isLeapYear(2023)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(1900)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(2000)); // Output: true

Notice that in the above, we don't have a 'default' case. And this is because we have initialized the isLeap variable with false. Had we just declared the variable without initialization with a value, we could've written a default case which would assign the value false to isLeap.

Also, the above version of switch-case code is slightly longer because we wanted to use one return statement in the end and used assignments until then. But if we refactor it, a shorter and more organized code would be this:

function isLeapYear(year) {

switch (true) {

case (year % 400 === 0):

return true;

case (year % 100 === 0):

return false;

case (year % 4 === 0):

return true;

default:

return false;

}

}

// Example usage:

console.log(isLeapYear(2024)); // Output: true

console.log(isLeapYear(2023)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(1900)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(2000)); // Output: true

Notice that since execution of a return statement in a function automatically ends the function call, the program does not read lines that follow that statement. So, in this example, we don't have to use the break statements necessarily.

Logical Deduction & Subsets for Better Structure

Switching back from switch-case to if-else logic, let's do some logical deduction. In our previous if-else logic, we went from generic cases to specific cases. What if we go in reverse order? We consider that a given year will be a leap year unless negated.

So, we start with the narrower cases of centenary years — for them, the rule is simple: to be negated, they need to be divisible by 100 but not by 400 (like years such as 1700, 1800, 1900).

In this process, since we've already accepted years like 2000 (or years divisible by 400) to be a leap year, we won’t test them for divisibility by 4 (because a number divisible by 400 would anyway be divisible by 4 as well).

In the next step, as we consider only the non-centenary years, we would simply negate the cases where the year is not divisible by 4 (years like 2023, 1996, and so on).

function isLeapYear(year) {

let isLeap = true;

if (year % 100 == 0 && year % 400 != 0) {

isLeap = false;

} else if (year % 4 != 0) {

isLeap = false;

}

return isLeap;

}

// Example usage:

console.log(isLeapYear(2024)); // Output: true

console.log(isLeapYear(2023)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(1900)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(2000)); // Output: true

Here you see, we first consider the centenary years and then non-centenary years — so they are mutually exclusive — and that’s why we use ‘else-if’ instead of if in the second conditional check. And in that process, we gain some efficiency over consecutive if blocks.

As this approach is about breaking the possible routes of being a leap year (or for that matter, not being a leap year) into subsets of years, depending upon how we break the possible years into subsets, we can construct the program alternatively as shown below:

function isLeapYear(year) {

let isLeap = false;

if (year % 400 == 0) {

isLeap = true;

} else if (year % 100 != 0 && year % 4 == 0) {

isLeap = true;

}

return isLeap;

}

// Example usage:

console.log(isLeapYear(2024)); // Output: true

console.log(isLeapYear(2023)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(1900)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(2000)); // Output: true

So, in brief, our deduction from the leap year rule is that years divisible by 400 (like 1600, 2000) are leap years, and out of all the other years they must be divisible by 4 but not divisible by 100 to be a leap year.

In taking this approach, we have combined conditions and that’s why we involved logical operators (&&, the logical AND operator). This has helped us reduce the length of the function. Instead of three conditional blocks, we are currently using two blocks — an if block and then an else (where we further check the condition, and thus we call it else-if rather than just else).

But now that we are just using almost a single ‘if-else’ construct and we are also delving into logical operators, let's unleash more power from the logical operators in the following approach.

Logical Operators Combining All True Conditions

This time let's just reorganize the logic from the previous approach (two subsets) to group all positive conditions together and then accept a year as a leap year. If that’s not met, then call it a non-leap year.

function isLeapYear(year) {

if ((year % 4 == 0 && year % 100 != 0) || year % 400 == 0) {

return true;

} else {

return false;

}

}

// Example usage:

console.log(isLeapYear(2024)); // Output: true

console.log(isLeapYear(2023)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(1900)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(2000)); // Output: true

This one looks good because it increases readability by organizing the positive conditions together. The only cost we incur here is that the condition in the if block is longer.

But with logical operators, it looks visually shorter and not complex (at least to programmers habituated to combining logical operators like this).

Dissecting further, since in the previous approach we said we could break the subsets in two different ways, we can have two corresponding two versions for this approach as well. The second one is the following:

function isLeapYear(year) {

if ((year % 100 == 0 && year % 400 != 0) || year % 4 != 0) {

return false;

} else {

return true;

}

}

// Example usage:

console.log(isLeapYear(2024)); // Output: true

console.log(isLeapYear(2023)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(1900)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(2000)); // Output: true

Applying Nitro with the Ternary Operator

As you progress in your programming-learning journey, at some point or other, you must have been elated to discover the possibility of writing ultra-short programs.

While logical operators help us do that, to activate the ‘Nitro’ mode, we must use a Ternary Operator — which basically makes our if-else blocks a single line.

function isLeapYear(year) {

return ((year % 4 == 0 && year % 100 != 0) || year % 400 == 0) ? true : false;

}

// Example usage:

console.log(isLeapYear(2024)); // Output: true

console.log(isLeapYear(2023)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(1900)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(2000)); // Output: true

By now, as a pro programmer, you must be pitying your rookie self. You think of those times when you used to declare and initialize a variable with a default value first and then reassign it with the value you wanted to return, and finally return the value held by that variable.

It has been a long time since you shunned that practice, and you now return what you need to return, and don’t consume unnecessary memory space for useless variables.

Making it a Single Line Arrow Function

Now that you have been boosted with Nitro, your programming technique is advancing like an arrow, on a mission to tear away the remnants of ES5 and boldly fly into the post-ES6 world. So you welcome arrow functions with open arms.

const isLeapYear = year => (year % 4 === 0 && (year % 100 !== 0 || year % 400 === 0));

// Example usage:

console.log(isLeapYear(2024)); // Output: true

console.log(isLeapYear(2023)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(1900)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(2000)); // Output: true

Previously, you skipped variables, and you skipped ‘if-else’ blocks. And now, you can even skip the return statement thanks to the arrow function having a single statement in its body. You also skip the parentheses around your argument as it is a single argument.

While singing the saga of shorter code, a point must be made that the shorter code is not necessarily the better code. It all depends on your users of the code (people who might read it and possibly collaborate/improve upon it).

If you are working with experienced programmers, this level of concision is fine. Just make sure you don’t exceed the line width beyond a certain number of spaces (80 characters recommended) so you don't trouble your coworkers with the need to handle horizontal scrollbars.

But if you are working with team members with varying levels of experience, or you are a teacher working with learners, then you must be conscious of the readability of your code for everyone.

Paradigm Shift: Declarative Programming

Anyway, we have discussed the logic of determining the leap year in the above examples. But let’s now dissect further to find more nuances of programming. And in that process let's move from imperative programming (as we have used so far) towards declarative programming (which is the end goal in this section).

Functions with Side Effects

Functions are said to have side effects when they modify non-local variables. In addition, a function that prints (logs) in the console is also considered a function with some side effects. That is because if a function does not have a side effect, a call to it can be replaced by its return value.

Functional Programming is a paradigm which dictates that our program should be like a pure function without side effects. A pure function means a function which always returns the same output given the same input. So, in its body, it depends on only the input parameter given from outside and no other global variable. Additionally, it should just return the output value without side effects or trying to modify anything outside its scope.

But consider the following variation of the program which does not specifically return any value representing the result. Instead, it logs the result as a statement (string) in the console. This is an example of a side effect.

function isLeapYear(year) {

if ((year % 4 == 0 && year % 100 != 0) || year % 400 == 0) {

console.log("leap year.");

} else {

console.log("not leap year.");

}

}

// Example usage:

let someValue = isLeapYear(2024); // Output: leap year.

console.log(someValue); // Output: undefined

Evidently, it does not follow the specification, as it needs to return a value of boolean type. A function can, of course, do both — printing and returning, like an alternative form of the above function.

function isLeapYear(year) {

if ((year % 4 == 0 && year % 100 != 0) || year % 400 == 0) {

console.log("leap year.");

return true;

} else {

console.log("not leap year.");

return false;

}

}

// Example usage:

let someValue = isLeapYear(2024); // Output: leap year.

console.log(someValue); // Output: true

But the mere fact that it is doing two things — returning a value and printing in the console — is the problem. A function should be made to do one thing for proper reusability. The ‘isLeapYear’ function should just determine if a year is a leap year. If we need to print anything about it, let that onus of doing the side effects lie with some other logger function(s).

// pure function

function isLeapYear(year) {

if ((year % 4 == 0 && year % 100 != 0) || year % 400 == 0) {

return true;

} else {

return false;

}

}

// functions with side effect

function simpleLeapYearLogger(isLeap) {

if (isLeap) {

console.log("Yes, a leap year!");

} else {

console.log("Sorry, not a leap year.");

}

}

function advancedLeapYearLogger(year, isLeap) {

if (isLeap) {

console.log(`The year ${year} is a leap year!`);

} else {

console.log(`The year ${year} is not a leap year!`);

}

}

// Example usage:

let currYear = 2024;

let check2024 = isLeapYear(currYear); // No Output/Side Effect, just retuned value.

simpleLeapYearLogger(check2024); // Output: Yes, a leap year!

advancedLeapYearLogger(currYear, check2024); // Output: The year 2024 is a leap year!

As you can see above, the function ‘isLeapYear’ is more reusable — with two different use cases in two separate logger functions. Also, had there been any mistake in the logic for the ‘isLeapYear’ function, it would have been easier to fix without touching the logger functions’ code.

Similarly, if you need to display the string logged in the console differently, you could modify the respective logger function without touching the leap year’s logic function. Thus, a function doing just one thing that it was supposed to do increases the reusability and maintainability of that function.

More About Functional Programming

In the above section, you have already ventured into the space of functional programming. And now is the time to delve deeper.

If I search the term ‘Functional Programming’ in Wikipedia, the first line states

“functional programming is a programming paradigm where programs are constructed by applying and composing functions.”

The phrase ‘composing function’ means building complex functions from simple ones. In our example, the leap year function is quite simple already. But to showcase the mechanism of function composition, let's create it out of component functions.

// component function

function divisible(dividend, divisor) {

return dividend % divisor == 0

}

// composed function

function isLeapYear(year) {

let isLeap = false;

divisible(year, 4) && (isLeap = true);

divisible(year, 100) && (isLeap = false);

divisible(year, 400) && (isLeap = true);

return isLeap;

}

// Example usage:

console.log(isLeapYear(2024)); // Output: true

console.log(isLeapYear(2023)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(1900)); // Output: false

console.log(isLeapYear(2000)); // Output: true

Side-Tracking: Short-Circuiting!

Above, you are using a function to build another function — a component-based approach that you also follow in the React JavaScript-based front-end library.

But wait, before we go further into React, what is that ‘&&’ doing in those three lines in the 'isLeapYear' function when we are not using any if-else statements there?

Welcome to the short-circuit evaluation of logical operators. In that process, an expression stops being evaluated as soon as its outcome is determined. So if two sides contain a logical AND (&&) in between, if the first side is false, this makes the whole expression false – so it does not read (not execute) the second side.

But if the first side is evaluated to be true, it further reads (executes) the second side for evaluation. And in that process, it does that assignment on the right-hand side of && in our example.

Similarly, the process when logical OR (||) is involved is such that if the left-hand side is evaluated as true, the whole expression is true (it needs one condition evaluated as true for || for the whole expression to be true). Then, the second side is ignored. The second side is read or executed only when the first side is evaluated as false.

You can use this kind of evaluation logic as a replacement for the ‘if’ condition checks. For more examples of how it works in different scenarios, read the section ‘Short-Circuiting of Logical Operators (&& and ||)’ in my blog post where I have discussed some nuances of JavaScript Operators.

Encapsulation and Declarative Programming

Returning to REACT and components, the idea of building composing functions or components is rooted in the need for encapsulation. With encapsulation, you can hide the complex details, like in a capsule, and use it repeatedly without bothering much about its underlying complexity.

Essentially, you just proclaim (declare) what you need rather than straining yourself with the workload and headache of how you can make it happen step-by-step with ‘do-this’ and ‘do-that’ type statements (imperatives).

That, briefly, is declarative programming for you.

Going Above & Beyond with Code Quality

So far, we have covered the logical structures and the programming paradigms, but now, let’s look at the third aspect: code quality.

Validations: Beyond the Basic Specifications

The requirements that we laid out at first just considered valid inputs. What if the function is called with arguments that are not the ideal ones — like a non-number, or even if a number but a non-integer?

To address that, we can build validation logic. To build validation logic, you need to think about all the different ways in which the input value (the argument passed to your function) may not be workable for you.

If one of those non-workable ways does come along, you need to return something that makes more sense — you can not give a verdict like true or false in that case. You may return something more neutral (like undefined or null) to indicate that the function encountered an invalid entry.

function isLeapYear(year) {

if (typeof year!="number" || year % 1 != 0 || year <= 0) return undefined;

return ((year % 4 == 0 && year % 100 != 0) || year % 400 == 0) ? true : false;

}

// Example usage:

console.log(isLeapYear(2024)); // Output: true

console.log(isLeapYear("TwentyTwentyFour")); // Output: undefined

console.log(isLeapYear(2023.99)); // Output: undefined

console.log(isLeapYear(0)); // Output: undefined

console.log(isLeapYear(-1)); // Output: undefined

console.log(isLeapYear("2024")); // Output: undefined

But if you noticed carefully, in our leap year logic check, we have evaluated just ordinary equality (==) instead of strict equality (===). We can't reap the benefit of that for a string format entry for a year like "2024".

If our intention is to strictly accept a number, the kind of validation we wrote is fine, and it would then be even more proper to use ===.

But if, on the other hand, we want to accept values like "2024", we must enhance our validation logic like so:

function isLeapYear(year) {

if (isNaN(Number(year)) || year % 1 != 0 || year <= 0) return undefined;

return ((year % 4 == 0 && year % 100 != 0) || year % 400 == 0) ? true : false;

}

// Example usage:

console.log(isLeapYear(2024)); // Output: true

console.log(isLeapYear("TwentyTwentyFour")); // Output: undefined

console.log(isLeapYear(2023.99)); // Output: undefined

console.log(isLeapYear(0)); // Output: undefined

console.log(isLeapYear(-1)); // Output: undefined

console.log(isLeapYear("2024")); // Output: true

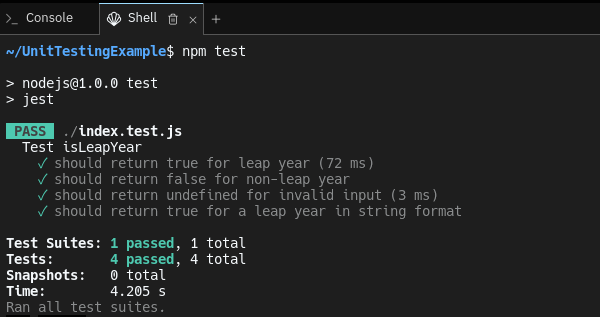

Testing it Out From the Outside

In the above two code blocks, we write our code and test it in the same place. But the code that goes into production will not have the opportunity to include such console logs that we have used extensively for demonstrating 'example usage' in the above code blocks.

This is where unit testing comes in. In unit testing, we first export the function for use in other places (files), then import that function in a test file. In that test file is where we run the test, build our cases, and finally run that test file to execute those tests.

I have used the Jest package to do this unit testing, and here is the code from my index file and test script file:

index.js

function isLeapYear(year) {

if (isNaN(Number(year)) || year % 1 != 0 || year <= 0) return undefined;

return ((year % 4 == 0 && year % 100 != 0) || year % 400 == 0) ? true : false;

}

module.exports = isLeapYear;

index.test.js

const isLeapYear = require('./index.js');

describe('Test isLeapYear', () => {

it('should return true for leap year', () => {

expect(isLeapYear(2020)).toBe(true);

});

it('should return false for non-leap year', () => {

expect(isLeapYear(2023)).toBe(false);

});

it('should return undefined for invalid input', () => {

expect(isLeapYear('TwentyTwentyFour')).toBe(undefined);

expect(isLeapYear('2023.99')).toBe(undefined);

expect(isLeapYear('0')).toBe(undefined);

expect(isLeapYear('-1')).toBe(undefined);

});

it('should return true for a leap year in string format', () => {

expect(isLeapYear("2024")).toBe(true);

});

});

I installed Jest using the command npm i jest. Then, I added jest as a value for test in the scripts object inside my package.json file. Then, as I ran npm test, it passed all my test cases, like so:

If you want to tweak and try this unit testing code, you can use and fork this replit project.

End Note

We've reviewed many programming concepts in the above exercise. And one key takeaway is that a program can be written in multiple ways.

There are typically many correct solutions to a programming problem. So beginner programmers should, therefore, think of the logic part of it (the algorithm) more than the exact execution steps when starting to solve a problem.

And by the way, if you're wondering why we have leap years, then this is for you: the time Earth takes to complete one revolution around the sun is not exactly 365 days (or 365 x 24 hours) but approximately one-quarter of a day extra.

This process may remind you of the modulus operator, represented by the symbol %, which returns the remainder of a division operation. Here, the approximate time (in hours) taken for one revolution of earth is being divided by 24 hours (that is, a day). It gives a remainder of about 6 hours.

const approxTimeHrsRev = 8766;

const hrsPerDay = 24;

let completedDaysEachYear;

let remainderHrsPerYear = 8766 % hrsPerDay;

completedDaysEachYear = (approxTimeHrsRev - remainderHrsPerYear) / hrsPerDay;

console.log(`After ${completedDaysEachYear} complete days, there is still about ${remainderHrsPerYear} hours left out each year.`);

// Output: After 365 complete days, there is still about 6 hours left out each year.

To account for those missed hours, we must adjust our calendars once every four years when those left-out portions add up to make — again approximately — a day.

Finally, because it is not exactly 6 hours, and a tiny bit more than that, we have to adjust every 100 and 400 years further.