Teams who work on GitHub rely on event data to collaborate. The data recorded as issues, pull requests, and comments become vital to understanding the project.

With the general availability of GitHub Actions, we have a chance to programmatically access and preserve GitHub event data in our repository. Making the data part of the repository itself is a way of preserving it outside of GitHub. It also gives us the ability to feature the data on a front-facing website, such as with GitHub Pages.

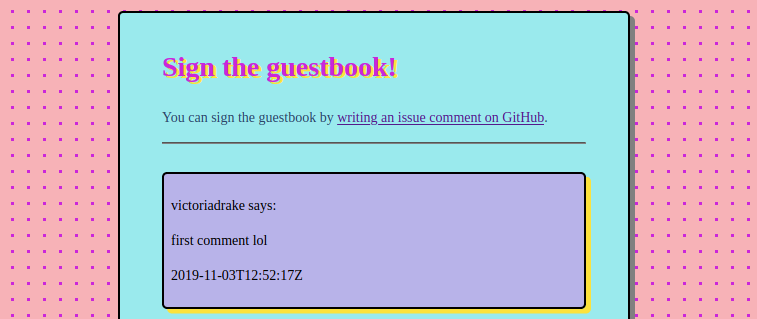

And, if you’re like me, you can turn GitHub issue comments into an awesome 90s guestbook page.

No matter the usage, the principle concepts are the same. We can use Actions to access, preserve, and display GitHub event data - with just one workflow file. To illustrate the process, I’ll take you through the workflow code that makes my guestbook shine on.

For an introductory look at GitHub Actions including how workflows are triggered, see A lightweight, tool-agnostic CI/CD flow with GitHub Actions.

Accessing GitHub event data

An Action workflow runs in an environment with some default environment variables. A lot of convenient information is available here, including event data. The most complete way to access the event data is using the $GITHUB_EVENT_PATH variable, the path of the file with the complete JSON event payload.

The expanded path looks like /home/runner/work/_temp/_github_workflow/event.json and its data corresponds to its webhook event. You can find the documentation for webhook event data in GitHub REST API Event Types and Payloads. To make the JSON data available in the workflow environment, you can use a tool like jq to parse the event data and put it in an environment variable.

Below, I grab the comment ID from an issue comment event:

ID="$(jq '.comment.id' $GITHUB_EVENT_PATH)"

Most event data is also available via the github.event context variable without needing to parse JSON. The fields are accessed using dot notation, as in the example below where I grab the same comment ID:

ID=${{ github.event.comment.id }}

For my guestbook, I want to display entries with the user’s handle, and the date and time. I can capture this event data like so:

AUTHOR=${{ github.event.comment.user.login }}

DATE=${{ github.event.comment.created_at }}

Shell variables are handy for accessing data, however, they’re ephemeral. The workflow environment is created anew each run, and even shell variables set in one step do not persist to other steps. To persist the captured data, you have two options: use artifacts, or commit it to the repository.

Preserving event data: using artifacts

Using artifacts, you can persist data between workflow jobs without committing it to your repository. This is handy when, for example, you wish to transform or incorporate the data before putting it somewhere more permanent. It’s necessary to persist data between workflow jobs because:

Each job in a workflow runs in a fresh instance of the virtual environment. When the job completes, the runner terminates and deletes the instance of the virtual environment. (Persisting workflow data using artifacts)

Two actions assist with using artifacts: upload-artifact and download-artifact. You can use these actions to make files available to other jobs in the same workflow. For a full example, see passing data between jobs in a workflow.

The upload-artifact action’s action.yml contains an explanation of the keywords. The uploaded files are saved in .zip format. Another job in the same workflow run can use the download-artifact action to utilize the data in another step.

You can also manually download the archive on the workflow run page, under the repository’s Actions tab.

Persisting workflow data between jobs does not make any changes to the repository files, as the artifacts generated live only in the workflow environment.

Personally, being comfortable working in a shell environment, I see a narrow use case for artifacts, though I’d have been remiss not to mention them. Besides passing data between jobs, they could be useful for creating .zip format archives of, say, test output data. In the case of my guestbook example, I simply ran all the necessary steps in one job, negating any need for passing data between jobs.

Preserving event data: pushing workflow files to the repository

To preserve data captured in the workflow in the repository itself, it is necessary to add and push this data to the Git repository. You can do this in the workflow by creating new files with the data, or by appending data to existing files, using shell commands.

Creating files in the workflow

To work with the repository files in the workflow, use the checkout action to first get a copy to work with:

- uses: actions/checkout@master

with:

fetch-depth: 1

To add comments to my guestbook, I turn the event data captured in shell variables into proper files, using substitutions in shell parameter expansion to sanitize user input and translate newlines to paragraphs. I wrote previously about why user input should be treated carefully.

- name: Turn comment into file

run: |

ID=${{ github.event.comment.id }}

AUTHOR=${{ github.event.comment.user.login }}

DATE=${{ github.event.comment.created_at }}

COMMENT=$(echo "${{ github.event.comment.body }}")

NO_TAGS=${COMMENT//[<>]/\`}

FOLDER=comments

printf '%b\n' "<div class=\"comment\"><p>${AUTHOR} says:</p><p>${NO_TAGS//$'\n'/\<\/p\>\<p\>}</p><p>${DATE}</p></div>\r\n" > ${FOLDER}/${ID}.html

By using printf and directing its output with > to a new file, the event data is transformed into an HTML file, named with the comment ID number, that contains the captured event data. Formatted, it looks like:

<div class="comment">

<p>victoriadrake says:</p>

<p>This is a comment!</p>

<p>2019-11-04T00:28:36Z</p>

</div>

When working with comments, one effect of naming files using the comment ID is that a new file with the same ID will overwrite the previous. This is handy for a guestbook, as it allows any edits to a comment to replace the original comment file.

If you’re using a static site generator like Hugo, you could build a Markdown format file, stick it in your content/ folder, and the regular site build will take care of the rest.

In the case of my simplistic guestbook, I have an extra step to consolidate the individual comment files into a page. Each time it runs, it overwrites the existing index.html with the header.html portion (>), then finds and appends (>>) all the comment files’ contents in descending order, and lastly appends the footer.html portion to end the page.

- name: Assemble page

run: |

cat header.html > index.html

find comments/ -name "*.html" | sort -r | xargs -I % cat % >> index.html

cat footer.html >> index.html

Committing changes to the repository

Since the checkout action is not quite the same as cloning the repository, at time of writing, there are some issues still to work around. A couple extra steps are necessary to pull, checkout, and successfully push changes back to the master branch, but this is pretty trivially done in the shell.

Below is the step that adds, commits, and pushes changes made by the workflow back to the repository’s master branch.

- name: Push changes to repo

run: |

REMOTE=https://${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}@github.com/${{ github.repository }}

git config user.email "${{ github.actor }}@users.noreply.github.com"

git config user.name "${{ github.actor }}"

git pull ${REMOTE}

git checkout master

git add .

git status

git commit -am "Add new comment"

git push ${REMOTE} master

The remote, in fact, our repository, is specified using the github.repository context variable. For our workflow to be allowed to push to master, we use the secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN variable.

Since the workflow environment is shiny and newborn, we need to configure Git. In the above example, I’ve used the github.actor context variable to input the username of the account initiating the workflow. The email is similarly configured using the default noreply GitHub email address.

Displaying event data

Nov 6, 2019 correction: GitHub Actions requires a Personal Access Token to trigger a Pages site build.

If you're using GitHub Pages with the default secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN variable and without a site generator, pushing changes to the repository in the workflow will only update the repository files. The GitHub Pages build will fail with an error, "Your site is having problems building: Page build failed."

To enable Actions to trigger a Pages site build, you'll need to create a Personal Access Token. This token can be stored as a secret in the repository settings and passed into the workflow in place of the default secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN variable. I wrote more about Actions environment and variables in this post.

With the use of a Personal Access Token, a push initiated by the Actions workflow will also update the Pages site. You can see it for yourself by leaving a comment in my guestbook! The comment creation event triggers the workflow, which then takes around 30 seconds to a minute to run and update the guestbook page.

Where a site build is necessary for changes to be published, such as when using Hugo, an Action can do this too. However, in order to avoid creating unintended loops, one Action workflow will not trigger another. Instead, it's extremely convenient to handle the process of building the site with a Makefile, which any workflow can then run. Simply add running the Makefile as the final step in your workflow job, with the repository token where necessary:

- name: Run Makefile

env:

TOKEN: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}

run: make all

This ensures that the final step of your workflow builds and deploys the updated site.

No more event data horizon

GitHub Actions provides a neat way to capture and utilize event data so that it’s not only available within GitHub. The possibilities are only as limited as your imagination! Here are a few ideas for things this lets us create:

- A public-facing issues board, where customers without GitHub accounts can view and give feedback on project issues.

- An automatically-updating RSS feed of new issues, comments, or PRs for any repository.

- A comments system for static sites, utilizing GitHub issue comments as an input method.

- An awesome 90s guestbook page.

Did I mention I made a 90s guestbook page? My inner-Geocities-nerd is a little excited.