by Geoffrey Bourne

The Man Who Knew Infinity: Coding Ramanujan’s Taxi

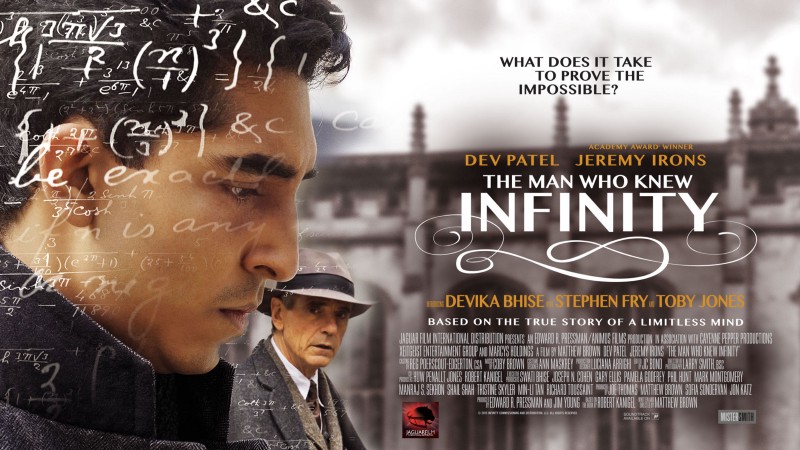

Have you see the movie (or read the book) The Man Who Knew Infinity?

This new movie — which stars Dev Patel and Jeremy Irons — explores Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan and his profound understanding, ingenuity, and love of math.

The film inspired me on both an intellectual and emotional level. But what really drew my attention was a particular five second scene.

The scene takes place in 1918. Ramanujan‘s mentor and friend G.H. Hardy quips that he had just taken taxi number 1729 and finds the number “a rather dull one.”

Ramanujan passionately replies, “No, Hardy, it’s a very interesting number! It’s the smallest number expressible as the sum of two cubes in two different ways.”

Ramanujan was able to see beyond the simple taxi cab number and into the depths of the expression behind it: a³ + b³ = c³ + d³…better known as Ramanujan’s Taxi. I thought this problem was fascinating and wondered how the code implementation would look. Little did I realize there were many optimization layers to this algorithm onion.

First Crack at Implementing Ramanujan’s Taxi

I started with a straight forward implementation written in Scala. The code, with performance timings, can be found on GitHub:

We begin with a brute-force implementation by looping though all combinations to find where a³ + b³ = c³ + d³. We achieve O(n⁴) performance because of the four loops used to calculate all values of a³, b³, c³, and d³ equal or less than parameter n, which bounds our search field.

This brute-force implementation, with O(n⁴) performance, kinda sucks. So, how can we do better?

We Can Do Better

First question to ask is: do we always need to calculate all the values of a³, b³, c³, and d³? Remember, the equation we are using is a³ + b³ = c³ + d³. If we solve for d³, we get d³ = a³ + b³ - c³. Thus, once we know a³, b³, and c³, we can calculate the value of d³ directly instead looping through all values of d³.

My next implementation, again in Scala, replaces the fourth loop with the calculation d³ = a³ + b³ — c³:

The 2nd version has O(n³) performance since we get to skip that final loop. Neat!

Third Time’s A Charm

We’re not done yet. There is a third, and the best yet, enhancement to consider. What if we don’t need to solve for all values of not only d³, but c³ too? A few things to understand:

- If we calculate all values of a³ and b³ equal to or less than n, we essentially have all possible values of not only a³ and b³, but also c³ and d³.

- The sum of a³ + b³ is equal to the sum of c³ + d³

- If the sum of #2 above for a given pair of integers (a³, b³) matches the sum of another pair of integers (a³, b³), we have in essence found the c³ and d³ pair.

If we store every combination of the sum of a³ + b³ and the corresponding pair (a³, b³), any sum that has two pairs means we have found a³ + b³ = c³ + d³ where the first pair in the list can be considered (a³, b³) and the next (c³, d³).

For example, if we iterate through the combinations of a³ + b³, we will store the sum 1729 with the pair (1³, 12³). Continuing to iterate, we will see another sum of 1729 arise, but this time with the pair (9³, 10³). Because we have two different pairs both summing to 1729, we have found a Ramanujan Taxi that solves for a³ + b³ = c³ + d³.

In the third version, we use a Hashmap to store the sum (key) and the corresponding list of pairs as a Sorted Set (value). If the list contains more than one pair, we’ve got a winner!

This implementation has O(n²) performance since we only need two loops to calculate the combinations for a³ and b³. Very neat!

I suspect there is a forth optimization where we only need to calculate values of a³ and derive b³ from a³ (the ‘b’ loop is just an offset of the ‘a’ loop) with O(n) performance.

Also, another challenge is to re-write the implementations as a functional programming pattern. I’ll leave that for you to explore.

An Amazing Movie, an Amazing Man

After watching The Man Who Knew Infinity, I was in awe of Ramanujan’s genius. By implementing his taxi algorithm — with its several performance optimizations — I got a glimpse of the beauty he saw in “No, Hardy, it’s a very interesting number!”

Ramanujan’s Taxi, at almost a century old, is still making new discoveries. Mathematicians at Emory University have found the number 1729 relates to elliptic curves and K3 surfaces — objects important today in string theory and quantum physics.

I expect we have only scratched the surface of Ramanujan’s taxi cab number and the man’s amazing genius.

About the Author: Geoffrey Bourne is the CEO of RETIRETY — helping people in or near retirement find a better way to retire.