by Abdul Kadir

The Strategy Pattern explained using Java

In this post, I will talk about one of the popular design patterns — the Strategy pattern. If you are not already aware, the design patterns are a bunch of Object-Oriented programming principles created by notable names in the Software Industry, often referred to as the Gang of Four (GoF). These Design patterns have made a huge impact in the software ecosystem and are used to date to solve common problems faced in Object-Oriented Programming.

Let’s formally define the Strategy Pattern:

The Strategy pattern defines a family of algorithms, encapsulates each one, and makes them interchangeable. Strategy lets the algorithm vary independently from the clients that use it

Alright with that out of the way, let’s dive into some code to understand what these words REALLY mean. We will take an example with a potential pitfall and then apply the strategy pattern to see how it overcomes the problem.

I will be showing you how to create a dope dog simulator program to learn the Strategy pattern. Here’s what our classes will look like: A ‘Dog’ superclass with common behaviors and then concrete classes of Dog created by subclassing the Dog class.

Here’s what the code looks like

public abstract class Dog {

public abstract void display(); //different dogs have different looks!

public void eat(){}

public void bark(){}

// Other dog-like methods

...

}The display() method is made abstract as different dogs have different looks. All the other subclasses will inherit the eat and bark behaviors or override it with their own implementation. So far so good!

Now, what if you wanted to add some new behavior? Let’s say you need a cool robot dog that can do all kinds of tricks. Not a problem, we just need to add a performTricks() method in our Dog superclass and we are good to go.

But wait a minute…A robot dog should not be able to eat right? Inanimate objects cannot eat, of course. Alright, how do we solve this problem then? Well, we can override the eat() method to do nothing and it works just fine!

public class RobotDog extends Dog {

@override

public void eat(){} // Do nothing

}Nicely done! Now Robot dogs cannot eat, they can only bark or perform tricks. What about rubber dogs though? They cannot eat nor can they perform tricks. And wooden dogs cannot eat, bark, or perform tricks. We cannot always possibly override methods to do nothing, it’s not clean and it just feels hacky. Imagine doing this on a project whose design specification keeps changing every few months. Ours is just a naive example but you get the idea. So, we need to find a cleaner way to solve this problem.

Can the interface solve our problem?

How about interfaces? Let’s see if they can solve our problem. Alright, so we create a CanEat and a CanBark interface:

interface CanEat {

public void eat();

}

interface CanBark {

public void bark();

}We have now removed the bark() and eat() methods from the Dog superclass and added them to the respective interfaces. So that, only the dogs that can bark will implement the CanBark interface and the dogs that can eat will implement the CanEat interface. Now, no more worrying about dogs inheriting behavior that they shouldn’t, our problem is solved…or is it?

What happens when we have to make a change in the eating behavior of the dogs? Let’s say from now onwards each dog must include some amount of protein with their meal. You now have to modify the eat() method of all the subclasses of Dog. What if there are 50 such classes, oh the horror!

So interfaces only partly solve our problem of Dogs doing only what they are capable of doing — but they create another problem altogether. Interfaces do not have any implementation code, so there’s zero code reusability and potential for lots of duplicate code. How do we solve this you ask? Strategy pattern comes to the rescue!

The Strategy Pattern

So we will do this step by step. Before we proceed, let me introduce you to a design principle:

Identify the parts of your program that vary and separate them from what stays the same.

It is actually very straightforward — the principle states to separate and “encapsulate” anything that changes frequently so that all the code that changes lives in one place. That way the code that changes will not have any effect on the rest of the program and our application is more flexible and robust.

In our case, the ‘bark ’and the ‘eat ’behavior can be taken out of the Dog class and can be encapsulated elsewhere. We know that these behaviors vary across different dogs and they must get their own separate class.

We are going to create two set of classes apart from the Dog class, one for defining eating behavior and one for the barking behavior. We will make use of interfaces to represent the behavior such as ‘EatBehavior ’ and ‘BarkBehavior ’ and the concrete behavior class will implement these interfaces. So, the Dog class is not implementing the interface anymore. We are creating separate classes whose sole job is to represent the specific behavior!

This is what the EatBehavior interface looks like

interface EatBehavior {

public void eat();

}And BarkBehavior

interface BarkBehavior {

public void bark();

}All of the classes that represent these behaviors will implement the respective interface.

Concrete classes for BarkBehavior

public class PlayfulBark implements BarkBehavior {

@override

public void bark(){

System.out.println("Bark! Bark!");

}

}

public class Growl implements BarkBehavior {

@override

public void bark(){

System.out.println("This is a growl");

}

public class MuteBark implements BarkBehavior {

@override

public void bark(){

System.out.println("This is a mute bark");

}Concrete classes for the EatBehavior

public class NormalDiet implements EatBehavior {

@override

public void eat(){

System.out.println("This is a normal diet");

}

}

public class ProteinDiet implements EatBehavior {

@override

public void eat(){

System.out.println("This is a protein diet");

}

}Now while we make concrete implementations by subclassing the ‘Dog’ superclass, naturally we want to be able to assign the behaviors dynamically to the dogs’ instances. After all, it was the inflexibility of the previous code that was causing the problem. We can define setter methods on the Dog subclass that will allow us to set different behaviors at runtime.

That brings us to another design principle:

Program to an interface and not an implementation.

What this means is that instead of using the concrete classes we use variables that are supertypes of those classes. In other words, we use variables of type EatBehavior and BarkBehavior and assign these variables objects of classes that implement these behaviors. That way, the Dog classes do not need to have any information about the actual object types of those variables!

To make the concept clear here’s an example that differentiates the two ways — Consider an abstract Animal class that has two concrete implementations, Dog and Cat.

Programming to an implementation would be:

Dog d = new Dog();

d.bark();Here’s what programming to an interface looks like:

Animal animal = new Dog();

animal.animalSound();Here, we know that animal contains an instance of a ‘Dog’ but we can use this reference polymorphically everywhere else in our code. All we care about is that the animal instance is able to respond to the animalSound() method and the appropriate method, depending on the object assigned, gets called.

That was a lot to take in. Without further explanation let’s see what our ‘Dog’ superclass looks like now:

public abstract class Dog {

EatBehavior eatBehavior;

BarkBehaviour barkBehavior;

public Dog(){}

public void doBark() {

barkBehavior.bark();

}

public void doEat() {

eatBehavior.eat();

}

}Pay close attention to the methods of this class. The Dog class is now ‘delegating’ the task of eating and barking instead of implementing by itself or inheriting it(subclass). In the doBark() method we simply call the bark() method on the object referenced by barkBehavior. Now, we don’t care about the object’s actual type, we only care whether it knows how to bark!

Now the moment of truth, let’s create a concrete Dog!

public class Labrador extends Dog {

public Labrador(){

barkBehavior = new PlayfulBark();

eatBehavior = new NormalDiet();

}

public void display(){

System.out.println("I'm a playful Labrador");

}

...

}What’s happening in the constructor of the Labrador class? we are assigning the concrete instances to the supertype (remember the interface types are inherited from the Dog superclass). Now, when we call doEat() on the Labrador instance, the responsibility is handed over to the ProteinDiet class and it executes the eat() method.

The Strategy Pattern in Action

Alright, let’s see this in action. The time has come to run our dope Dog simulator program!

public class DogSimulatorApp {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Dog lab = new Labrador();

lab.doEat(); // Prints "This is a normal diet"

lab.doBark(); // "Bark! Bark!"

}

}How can we make this program better? By adding flexibility! Let’s add setter methods on the Dog class to be able to swap behaviors at runtime. Let’s add two more methods to the Dog superclass:

public void setEatBehavior(EatBehavior eb){

eatBehavior = eb;

}

public void setBarkBehavior(BarkBehavior bb){

barkBehavior = bb;

}Now we can modify our program and choose whatever behavior we like at runtime!

public class DogSimulatorApp {

public static void main(String[] args){

Dog lab = new Labrador();

lab.doEat(); // This is a normal diet

lab.setEatBehavior(new ProteinDiet());

lab.doEat(); // This is a protein diet

lab.doBark(); // Bark! Bark!

}

}Let’s look at the big picture:

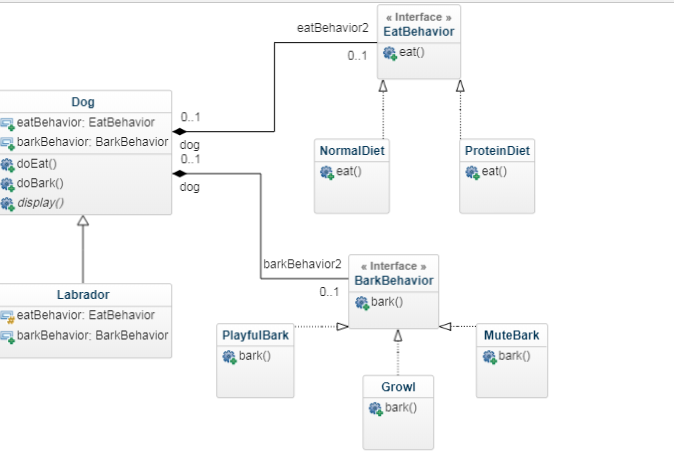

We have the Dog superclass and the ‘Labrador’ class which is a subclass of Dog. Then we have the family of algorithms (Behaviors) “encapsulated” with their respective behavior types.

Take a look at the formal definition that I gave at the beginning: the algorithms are nothing but the behavior interfaces. Now they can be used not only in this program but other programs can also make use of it. Notice the relationships between the classes in the diagram. The IS-A and HAS-A relationships can be inferred from the diagram.

That’s it! I hope you have gotten a big picture overview of the Strategy pattern. The Strategy pattern is extremely useful when you have certain behaviors in your app that change constantly.

This brings us to the end of the Java implementation. Thank you so much for sticking with me so far! If you are interested to learn about the Kotlin version, stay tuned for the next post. I talk about interesting language features and how we can reduce all of the above code in a single Kotlin file :)

P.S

I have read the Head First Design Patterns book and most of this post is inspired by its content. I would highly recommend this book to anyone who is looking for a gentle introduction to Design Patterns.