Have you ever needed to loop through multiple iterables in parallel when coding in Python?

In this tutorial, we'll use Python's zip() function to efficiently perform parallel iteration over multiple iterables.

Here's what we'll cover in this post:

- How to Use the 'in' Operator in Python to Traverse Iterables

- Why Using Python's range() Object is Not an Optimal Choice Always

- How Python's zip() Function Works

- How the zip() Function Creates an Iterator of Tuples

- How to Use Python's zip() Function - Try it Yourself!

- What Happens When the Iterables are of Different Lengths?

- What Happens When You Pass in One or No Iterable to the zip() Function?

- How to Use the zip_longest() Function in Python

How to Use the 'in' Operator in Python to Traverse Iterables

Before we go ahead and learn about the zip() function, let's quickly revisit how we use the in operator with a for loop to access items in an iterable (lists, tuples, dictionaries, strings etc.). The snippet below shows the general syntax:

for item in list_1:

# do something on itemIn simple terms, we tell the Python interpreter: "Hey there! Please loop through list_1 to access each item and do some operation on each item."

What if we had more than one list (or any iterable) ? Say, N lists – you may insert your favorite number in place of N. Things may seem a bit difficult now, and the following approach won't work:

# Example - 2 lists, list_1 and list_2

for i1 in list_1:

for i2 in list_2:

# do something on i1 and i2Please note that the above code:

- first taps into the first item in

list_1, - then loops through

list_2accessing each item inlist_2, - then accesses the second item in

list_1, - and loops through the whole of

list_2again, and - does this until it traverses the whole of

list_1

Clearly, this isn't what we want. We need to be able to access items at a particular index from both the lists. This is precisely what is called parallel iteration.

Why Using Python's range() Object is Not an Optimal Choice Always

You may think of using the range() object with the for loop. "If I know that all lists have the same number of items, can I not just use the index to tap into each of those lists, and pull out the item at the specified index?"

Well, let's give it a try. The code is in the snippet below. You know that all the lists – list_1, list_2,..., list_N – contain the same number of items. And you create a range() object as shown below and use the index i to access the item at position i in each of the iterables.

for i in range(len(list_1)):

# do something on list_1[i],list_2[i],list_3[i],...,list_N[i]As you might have guessed by now, this works as expected only when all the iterables contain the same number of items.

Consider the case where one or more of the lists are updated – say, one list may have an item removed from it, and another may have an item added to it. This would cause confusion:

- You may run into

IndexErrorsas you're accessing items at indices that are no longer valid because the item at the index has been removed, or - You may not be accessing newly added items at all as they are at indices not currently in the range of accessed indices.

Let's now see how Python's zip() function can help us iterate through multiple lists in parallel. Read ahead to find out.

How Python's zip() Function Works

Let's start by looking up the documentation for zip() and parse it in the subsequent sections.

Syntax: zip(*iterables) – the zip() function takes in one or more iterables as arguments.

Make an iterator that aggregates elements from each of the iterables.

1. Returns an iterator of tuples, where the i-th tuple contains the i-th element from each of the argument sequences or iterables.

2. The iterator stops when the shortest input iterable is exhausted.

3. With a single iterable argument, it returns an iterator of 1-tuples.

4. With no arguments, it returns an empty iterator. – Python Docs

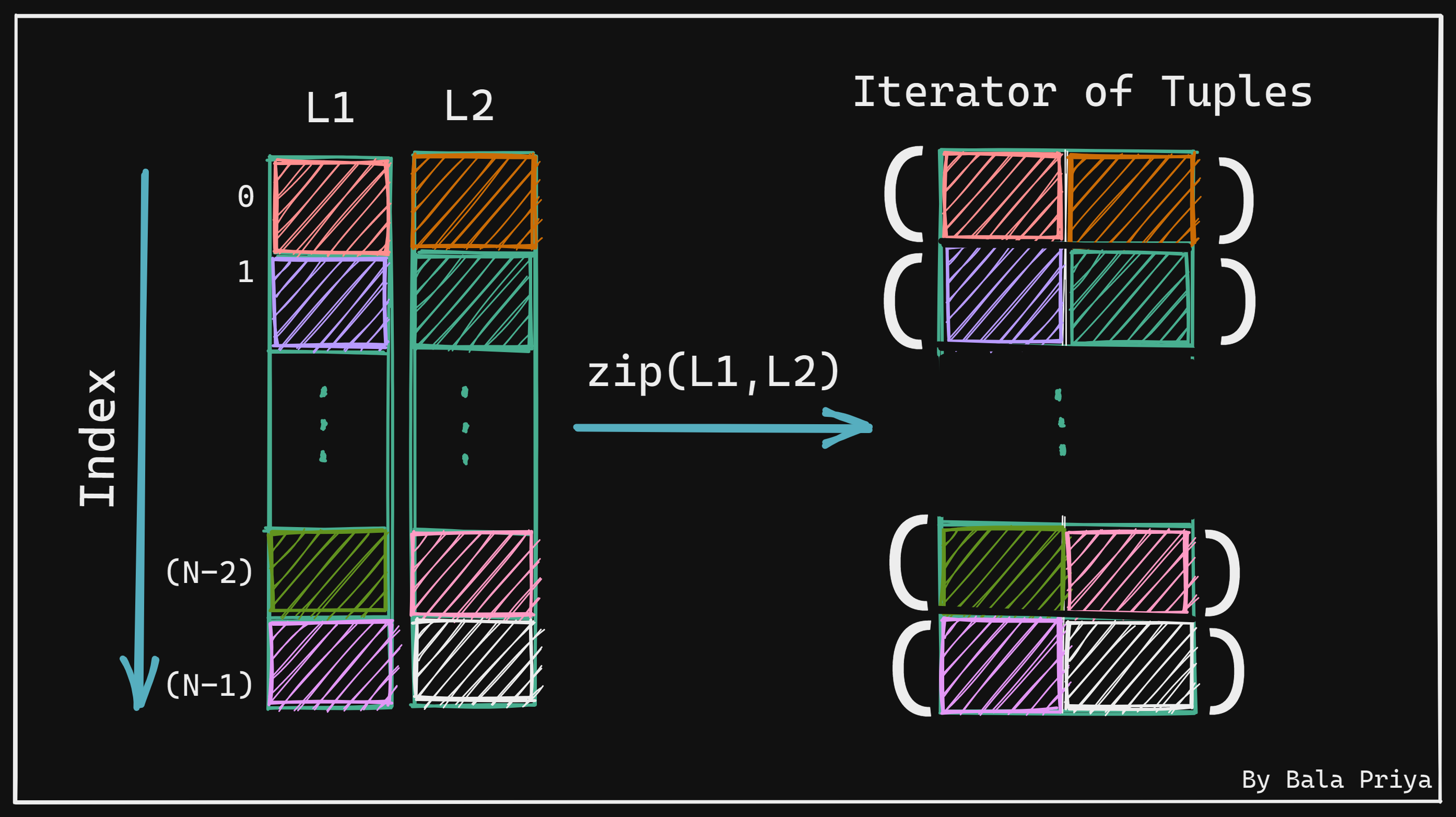

How the zip() Function Creates an Iterator of Tuples

The following illustration helps us understand how the zip() function works by creating an iterator of tuples from two input lists, L1 and L2. The result of calling zip() on the iterables is displayed on the right.

- Notice how the first tuple (at index

0) on the right contains 2 items, at index0inL1andL2, respectively. - The second tuple (at index

1) contains the items at index1inL1andL2. - In general, the tuple at index

icontains items at indexiinL1andL2.

Let's try out a few examples in the next section.

How to Use Python's zip() Function – Try it Yourself!

Try running the following examples in your favorite IDE.

As a first example, let's pick two lists L1 and L2 that contain 5 items each. Let's call the zip() function and pass in L1 and L2 as arguments.

L1 = [1,2,3,4,5]

L2 = ['a','b','c','d','e']

zip_L1L2 = zip(L1,L2)

print(zip_L1L2)

# Sample Output

<zip object at 0x7f92f44d5550>

Let's cast the zip object into a list and print it out, as shown below.

print(list(zip_L1L2))

# Output

[(1, 'a'), (2, 'b'), (3, 'c'), (4, 'd'), (5, 'e')]What Happens When the Iterables are of Different Lengths?

If you go back to the documentation, the second item in the numbered list reads: "The iterator stops when the shortest input iterable is exhausted."

Unlike working with the range() object, using zip() doesn't throw errors when all iterables are of potentially different lengths. Let's verify this as shown below.

Let's remove 'e' from L2, and repeat the steps above.

L1 = [1,2,3,4,5]

L2 = ['a','b','c','d']

zip_L1L2 = zip(L1,L2)

print(list(zip_L1L2))

# Output

[(1, 'a'), (2, 'b'), (3, 'c'), (4, 'd')]We now see that the output list only contains 4 tuples and the item 5 from L1 has not been used. So far so good!

What Happens When You Pass in One or No Iterable to the zip() Function?

Let's revisit the items 3 and 4 of the documentation again.

"With a single iterable argument, it returns an iterator of 1-tuples.

With no arguments, it returns an empty iterator."

Let's go ahead and verify this. Observe how we get 1-tuples when we pass in only L1 in the code snippet below:

L1 = [1,2,3,4,5]

zip_L1 = zip(L1)

print(list(zip_L1))

# Output

[(1,), (2,), (3,), (4,), (5,)]

When we call the zip() function with no arguments, we get an empty list, as shown below:

zip_None = zip()

print(list(zip_None))

# Output

[]Let's now create a more intuitive example. The code snippet below shows how we can use zip() to zip together 3 lists and perform meaningful operations.

Given a list of fruits, their prices and the quantities that you purchased, the total amount spent on each item is printed out.

fruits = ["apples","oranges","bananas","melons"]

prices = [20,10,5,15]

quantities = [5,7,3,4]

for fruit, price, quantity in zip(fruits,prices,quantities):

print(f"You bought {quantity} {fruit} for ${price*quantity}")

# Output

You bought 5 apples for $100

You bought 7 oranges for $70

You bought 3 bananas for $15

You bought 4 melons for $60

Now we understand how the zip() function works, and we know its limitation that the iterator stops when the shortest iterable is exhausted. So let's see how we can overcome this limitation using the zip_longest() function in Python.

How to Use the zip_longest() Function in Python

Let's import the zip_longest() function from the itertools module:

from itertools import zip_longestLet's now try out an earlier example of L2 containing one item less than L1.

L1 = [1,2,3,4,5]

L2 = ['a','b','c','d']

zipL_L1L2 = zip_longest(L1,L2)

print(list(zipL_L1L2))

# Output

[(1, 'a'), (2, 'b'), (3, 'c'), (4, 'd'), (5, None)]Notice how the item 5 from L1 is still included. But as there's no matching item in L2, the second element in the last tuple is None.

You can customize it more if you want to. For example, you can replace None with a more indicative term such as Empty, Item Not Found, and so on. All you have to do is set the optional fillvalue argument to the term that you wish to display when there's no matching item in an iterable when you call zip_longest().

I hope you now understand Python's zip() and zip_longest() functions.

Thank you for reading! See you all soon in another post.