First, what's a cache?

In general terms, a cache (pronounced "cash") is a type of repository. You can think of a repository as a storage depot. In the military, this would be to hold weapons, food, and other supplies needed to carry forward a mission.

In computer science, these "supplies" are termed resources, where the resources are scripts, code, and document content. The latter is sometimes more specifically referred to as "assets" such as text, static data, media, and hyperlinks, but here I'll just use the one term resources.

The distinction between a cache and other types of repositories

A cache's primary purpose is to speed up retrieval of web page resources, decreasing page load times. Another critical aspect of a cache is to ensure that it contains relatively fresh data.

This article will cover two prevalent methods of caching: browser caching and Content Delivery Networks (CDNs).

Besides caches, other repositories come into play in web architectures; often these are designed to hold vast troves of data. They are not as focussed, though, on retrieval performance.

For example, Amazon Glacier is a data repository that is designed to store data cheaply, but not retrieve it quickly. An SQL database, on the other hand, is designed to be flexible, up-to-date, and fast, but is seldom cheap and not usually as fast as a cache.

The Browser Cache: a memory cache

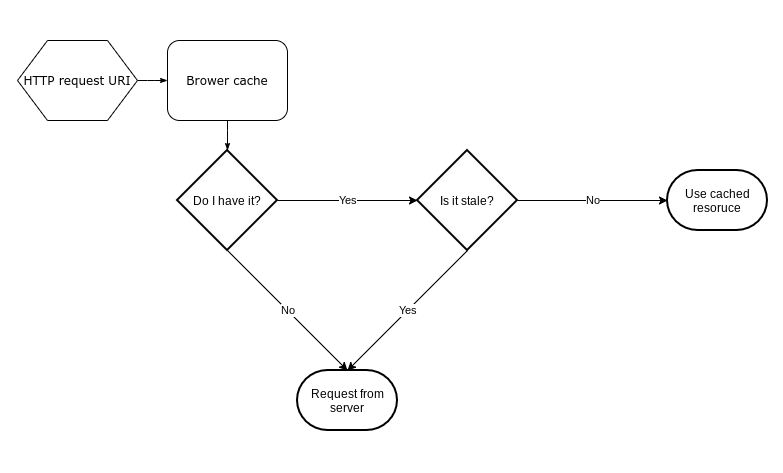

A memory cache stores resources locally on the computer where the browser is running. While the browser is active, retrieved resources will be stored on the computer's physical memory (RAM), and possibly also on hard drive.

Later, when the exact same resources are needed when revisiting a web page, the browser will pull those from the cache instead of the remote server. Since the cache is stored locally, in fast memory, those resources are fetched quicker, and the page loads faster.

Speed of resource retrieval is of the essence, but so is the necessity that the resources be fresh. A stale resource is one that is out-of-date and may no longer be valid.

Part of the job of the browser is to identify which cached resources are stale, and refetch those that are. Since a web page typically has may resources, there will usually be a mix of stale and fresh versions in the cache.

How does the browser know what is stale in the cache?

The answer is not simple, but there are two main approaches: cache-busting and HTTP header fields.

cache-busting

Cache-busting is a server-side technique that ensure that the browser only fetches fresh resources. It does this indirectly.

While cache-busting may sound dramatic, it really doesn't bust anything, and doesn't even touch what is already cached on a browser. All cache-busting does is change the original resource's URI in a way that makes it appear to the browser that the resource is completely new. Since it looks new, it will not be in a browser's cache. The old version of the cached resource will still be cached, but eventually will wither and die, never to be accessed again.

Say I have a web page located at www.foobar.com/about.html which says everything about foobar.com that you would ever want to know. Once you visit that page, it and the resources associated with it are cached by the browser.

Later, foobar.com is bought out by the Quxbaz corporation, and the about page's content undergoes significant changes. The browser's cache won't have that new content, yet it may still believe the content it has is current and will never try to refetch it.

What do you, the Quxbaz web administrator, do to ensure all new content is pushed out?

Since the browser relies on the URI to find items in the cache, if the URI of a resource changes then it's like the browser has never seen it before it goes to fetch that resource from the server.

Thus, by changing the resource URI from www.foobar.com/about.html to www.foobar.com/about2.html (or to www.quxbaz.com/about.html), the browser will not find any cache resource associated with that URI, and do a full fetch from the server. The resource might be substantially the same as the original under the old URI, but the browser doesn't know that.

You don't have to change the page name, though. Since the URI also includes a query string by definition, you can add a version parameter to the URI: www.foobar.com/about.html?v=2hef9eb1.

In this case, the version parameter v is set new a new generated hash value whenever the content changes, or is triggered by some other process, such as a server restart. The browser sees that the query string has changed, and because query strings can affect what will be returned, it will fetch an up-to-date resource from the server.

Neither of these techniques will work if the old URI is directly accessed from a bookmark. Unless the browser was instructed to revalidate the URI on the last cached request (or the cached resource expired), it won't do a full fetch to refresh its cache. This brings us to the next topic.

HTTP header fields

Every resource request come with some meta information known as the header. Conversely, every response also has header information associated with it.

In some cases, the browser sees the response header values, and changes corresponding values in subsequent request headers. Among these header values are those that affect how resource caching is performed on the browser.

HEAD requests and conditional requests

A HEAD request is like a truncated GET or a POST request. Instead of requesting the complete resource, a HEAD request only requests the header fields that would otherwise be returned on a full request.

The header of a resource is generally going to be much smaller (in number of total bytes) than the resource data associated with it (the "body" of the response). The header information is sufficiently informative to allow the browser to determine the freshness of the resource in its cache.

HEAD requests are often used to verify the validity of a server resource (that is, does the resource still exist, and if so, has it been updated since the browser last accessed it?). The browser will use what's in its cache if the HEAD request indicates the resource is valid, otherwise it will perform a full GET or POST request and refresh its cache with what is returned.

With a conditional request, the browser sends fields in the header describing the freshness of its cached resource. This time, the server determines if the browser's cache is still fresh.

If it is, the server returns a 304 response with just the resource's header information, and no resource body (the data). If the browser's cache is determined to be outdated, then the server will return a full 200 OK response.

This mechanism is faster than using HEAD requests, since it eliminates the possibility of having to issue two requests instead of one.

The above simplifies what can be a pretty complicated process. There's a lot of fine-tuning involved in caching, but it all is controlled through header fields, the most important of which is cache-control.

Cache-Control

When responding to a request, the server will send header fields to the browser indicating what behavior is should adapt when caching. If I load the page at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uniform_Resource_Identifier, the response contains this in its header record:

cache-control: private, s-maxage=0, max-age=0, must-revalidate

private means that only the browser should cache the document content.

s-maxage and max-age are set to 0. The s-maxage value is for proxy servers with caches, whereas max-age is intended for the browser. The effect of setting max-age alone is that the cached resource expires immediately, yet it may still be used (even though stale) during page reloads while in the same browser session.

A stale resource may be revalidation through a HEAD request, which might be followed by a GET or POST request, depending on the response. The must-revalidate directive commands the browser to revalidate the cached resource if it is stale.

Since max-age is set to 0 in this case, the cached resource is immediately stale once received. The combination of the two directives is equivalent to the single directive no-cache.

The two settings ensure that the browser always revalidates the cached resource, whether still in the same session or not.

Cache-control directives are very extensive, and at times confusing – they're a topic in their own right. A complete documented list of directives can be found here.

E-tag

This is a token that the server sends and the browser retains until the next request. This is only used when the browser knows that the resource's cache lifetime has expired.

E-tags are server-generated hash values, which often use the resource's physical file name and last modified date on the server as a seed. When a resource file is updated, the modified date changes, and a new hash value is generated and sent in the response header to the request.

Other header tags affecting caching

The header tags expires and last-modified are all but obsolete, yet are still sent by most servers for backward compatibility with older browsers. An example:

expires: Thu, 01 Jan 1970 00:00:00 GMT

last-modified: Sun, 01 Mar 2020 17:59:02 GMT

Here, the expires is set to the zeroth date (historically, from the UNIX operating system). That indicates that the resource expires immediately, just as max-age=0 does. Last-modified tells the browser when the latest update was made to the resource, which it can then use to decide if it should refetch it rather than use the cache value.

Forcing a cache refresh from the browser

What's a hard reload?

A hard reload forces the refetch of all resources on a page, whether they're content, scripts, stylesheets or media. Pretty much everything, right?

Well, some resources are may not be explicitly included on a page. Instead, they can be fetched dynamically, usually after everything explicit has loaded.

The browser doesn't know ahead of time that this will happen, and when it does, the later requests (initiated by scripts, usually) will still use cached copies of those resources if available.

What's clear cache and hard reload?

This operation clears the entire browser cache, which has the same effect as a hard reload, but additionally causes dynamically loaded resources to be fetched as well – after all, there's nothing in the cache, so there is no choice!

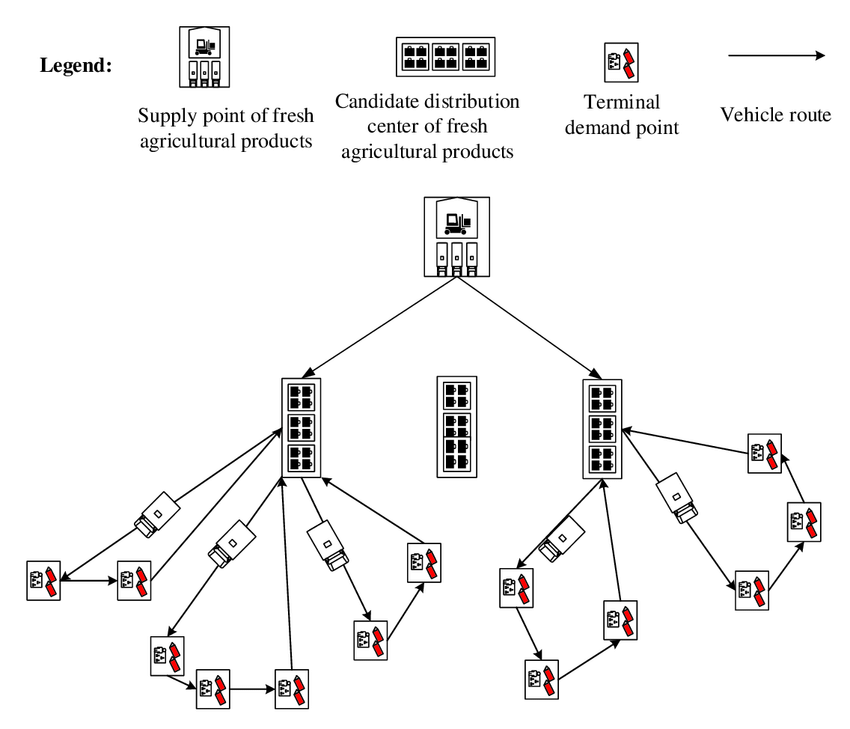

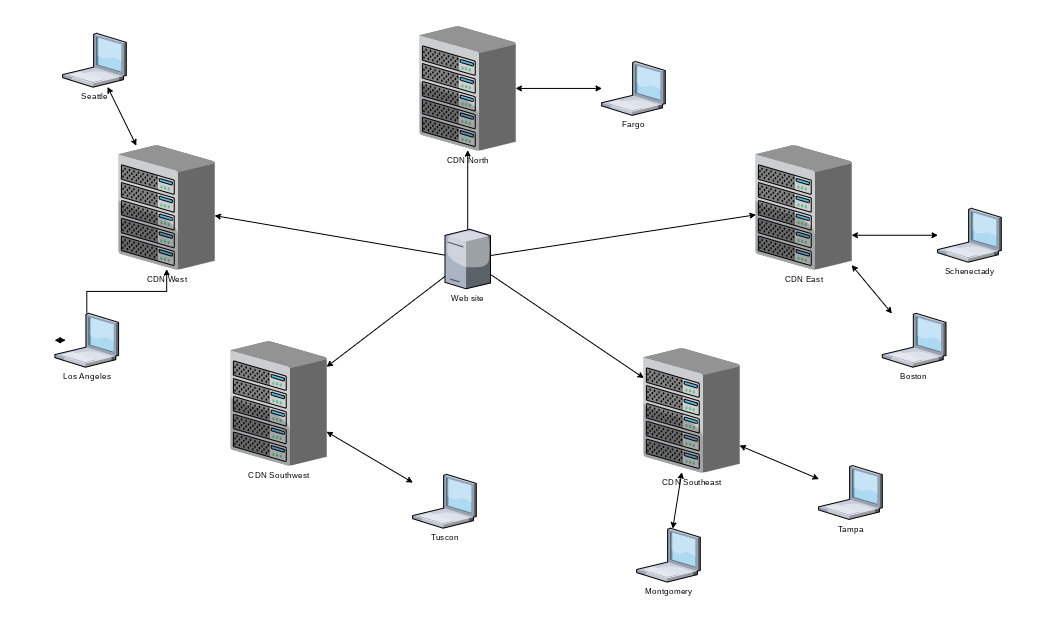

Content Delivery Networks: a geo-located cache

A CDN is more than just a cache, but caching is one of its jobs. A CDN stores data in geographically distributed locations so that round-trip times to and from a geographically local browser are reduced.

Browser requests are routed to a nearby CDN, thereby shortening the physical distance response data has to travel. CDNs also are able to handle large amounts of traffic, and provide security against some types of attacks.

A CDN gets its resources through an Internet Exchange Point (IXP), nodes that are part of the backbone of The Internet (in caps). There are steps to take to set up request routing to go to a CDN instead of the host server. The next step is to make sure the CDN has the current content of your website.

In the old days, most CDNs supported the push method: a website would push new content to a CDN hub, which would then get distributed to geographically dispersed nodes.

Nowadays, most CDNs use the caching protocols described above (or similar) to 1) download new resources, and 2) refresh existing ones. The browser still has its cache, and none of that changes. All a CDN does is make those transfers of new resources faster.