by Jonathan Solórzano-Hamilton

Those things you missed — all because you were too cocky to use a checklist

Thirty-six seconds after launch, lightning struck the Apollo 12 and its six million pounds of high explosive fuel.

The instruments blacked out.

Twenty-two seconds later lightning struck again. What few instruments remained started flashing red failure lights.

The “you’re about to die” alarm started blaring.

Over the radio the crew heard the voice of John Aaron: “Flight, try SCE to Aux.” Astronaut Alan Bean flipped the tiny switch immediately.

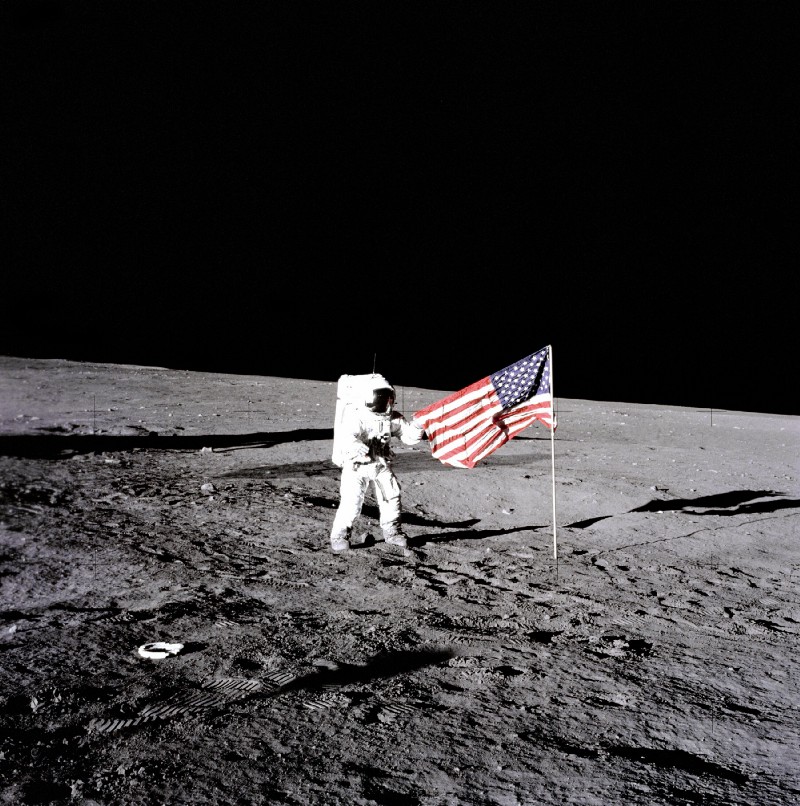

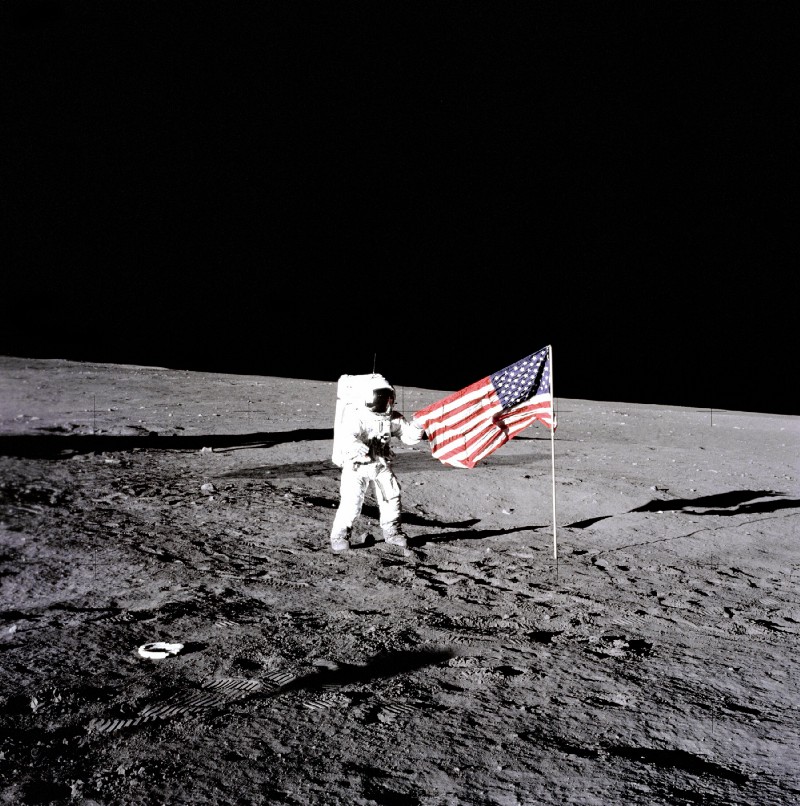

And that’s why I’m showing you this historic photograph instead of a picture of three headstones at Arlington National Cemetery.

November 14, 1969 was the day that John Aaron became known as the steely-eyed missile man.

How did he know which one switch — out of 566 — would save the launch? Because he’d run the checklist hundreds and hundreds of times. The SCE auxiliary power switch wasn’t on the checklist.

Then again, getting struck by lightning wasn’t either.

But he’d run the normal steps so many times that they were all rote. So when they ran simulations, every anomaly stuck out in his mind.

One time a year prior they had simulated a double lightning strike. The simulated mission failed with the astronauts simulated as dead.

Aaron and Bean studied the manuals and figured out what would save them if it ever happened again. When it did happen again a year later during the real deal, they knew what to do and saved the mission.

Surgery is safer in hospitals where surgeons follow a checklist, as author Dr. Atul Gawande noted. These were modeled after the checklists used by commercial pilots.

Both occupations carry a lot of responsibility for people’s lives. There are about 41,000 surgeons vs. 104,000 commercial pilots in the United States. That’s a pretty comparable labor pool.

The annual mortality rate on the surgical table is in the tens of thousands. The odds of dying on a commercial flight are somewhere in the one in tens or hundreds of millions per year.

One of these professions purports individual genius. The other assumes we will fail without heavily-regulated training and checklists.

Checklists require checking more than list items — they check our egos, too. When we pick up a checklist we’re tacitly admitting that we aren’t perfect.

Most of us aren’t astronauts, pilots, or surgeons. But we’re still fallible humans working with other fallible humans.

We make mistakes, we forget things, and we get sloppy.

I work in software development. It has no shortage of prima donnas who believe they’re above it all.

I still make them use checklists.

Every bonehead mistake I’ve made has taken place when I let my ego convince me I could skip the checklist. That time we nearly destroyed a million-dollar experiment — we didn’t have a checklist before that incident. Did we write one immediately after? You bet.

I don’t actually know what you missed when you didn’t use a checklist. But you don’t either. That’s the problem.

You won’t find out until it’s too late.

Even if you are lucky enough to dodge a catastrophe, you’re still hurting yourself in the long run. You’re devoting precious brain power to remembering mundane, repeatable processes.

You may miss your John Aaron moment because you were too busy avoiding a goof-up to notice an anomaly.

In my current profession there are plenty of opportunities to use checklists to improve process. Code review checklists. Testing checklists. Deployment checklists.

These checklists don’t have to be long. We’re not trying to put people on the moon, after all. But each checklist must be enough to mitigate the risks of the process and product it supports.

The next time you’re preparing to launch something new, be it an app or a Saturn V, make sure to ask yourself: “Did I follow the checklist?”