by P. Daniel Tyreus

I turned my mobile app into a chatbot. Here’s why.

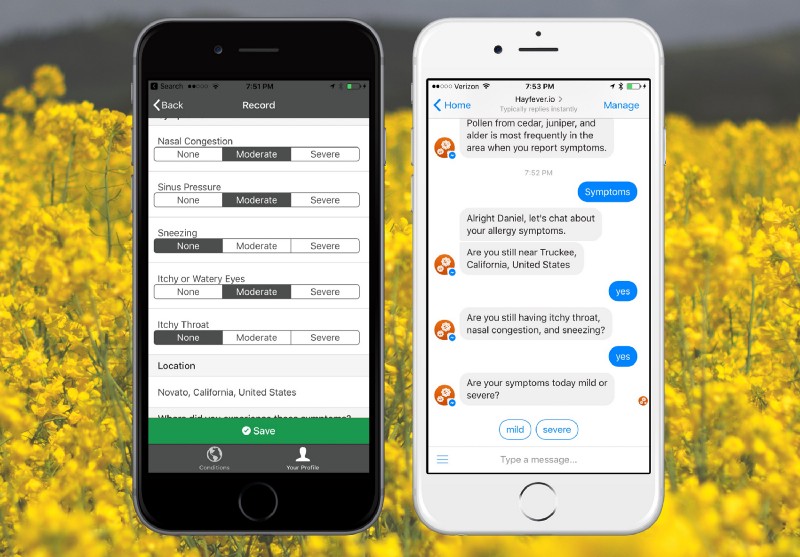

Just under a year ago, I embarked on a quest to better understand my seasonal allergies. In support of this quest, I spent a few weekends writing an iOS and Android app called Hayfever. With the app, I could log my symptoms and it would collect data about the allergens in the area. My grand idea was that if enough people logged symptoms using the app, we could crunch the numbers and start to learn from the trends.

Early users liked the idea behind Hayfever. Despite that, it did not get downloaded very much. After looking at the options, I decided to ditch the traditional app interface for a conversational one and to convert Hayfever to a chatbot. This post explains the reasoning that lead me down this path.

Analyzing the Trends

I’m not completely surprised that Hayfever had trouble getting downloads. There are some competing apps with good ranking in the app stores. Most of these are made by the same companies that are trying to sell OTC allergy medications. I have my doubts about the actual motives behind them. But these are big companies that have a lot of advertising budget to spend promoting their apps.

On top of that, there are some trends in the industry that make things more difficult for independent developers. In September of 2016, Recode reported that “half of U.S. smartphone users download zero apps per month.” That’s also not a new trend, as we have been seeing similar numbers since 2014.

This doesn’t mean people aren’t using apps anymore. In fact, in its year-end retrospective, App Annie said time spent in apps grew more than 25 percent in 2016 in the United States. But there is more to that story. Consumers are spending over 84 percent of their time on their smartphones using using just five non-native apps they’ve installed from the App Store. In summary, consumers are using mobile apps, but it’s primarily existing apps from a handful of companies.

Indeed, according to Sensor Tower data, in Q3 2016, the top 5 iOS app downloads were Pokémon GO, Uber, Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, and Facebook. Three of these are owned by the same company and you may notice that two of the top 5 are messaging apps. Similarly, App Annie reports that top five apps by downloads in 2016 on iOS and Google play were Facebook, WhatsApp Messenger, Facebook Messenger, Instagram, and Snapchat.

Here is a summary of what we know from these data:

- We know that people are spending a lot of time using apps on their phones.

- We know that people mostly use about five non-native apps.

- We know app download numbers reflect this pattern. The average user downloads zero new apps per month.

- Of the apps that people do download, a select few rack up most of the installs.

- Of the top apps downloaded in 2016, roughly half are messaging platforms.

I’m willing to speculate that it’s easier to acquire a user if the user doesn’t have to download a new app to use a service. I’m also willing to speculate that users are more likely to continue using a service that’s integrated into an app they already use. Finally, I’m willing to gamble that more and more people are comfortable chatting with a bot on a messaging platform.

Adapting to the Trends

After studying the trends outlined above, it’s clear to me that the slow adoption Hayfever saw in it’s first year was no fluke. This is the reality of the current mobile app development environment. Yet, I still believe that Hayfever addresses a real concern and offers a valuable service. After all there are 50 million nasal allergy sufferers in the United States and rising. So after some consideration, I was able to come up with three options for moving forward:

- Spend money and time on paid downloads and growth initiatives.

- Introduce a viral component to the app to encourage organic growth.

- Pivot to reduce installation friction and go where there are already users.

My budget for buying advertising and paid downloads is very limited. Hayfever is a side project and I can’t pour money into it. While I would love to introduce a viral component, I haven’t been able to come up with a good hook yet. So when I look at this from a pure user acquisition angle, converting Hayfever to a chatbot seems like a promising choice. But user acquisition is only the first piece of the puzzle. To keep those users their experience with the conversational UI has to be positive.

Arguments Against a Conversational User Interface

There are also some arguments against chatbots and conversational user interfaces. Despite a tremendous amount of hype in 2016, there have not been any breakout chatbot successes. There has been nothing even close to the scale of Pokemon GO. In fact, the most successful apps of the on-demand economy seem to show that a conversational UI is less useful than a well-designed graphical UI. Uber, one of the most downloaded apps of 2016, is a perfect example. Uber has shown us that millions of users would rather tap a button on a phone than call a taxi company and talk to a dispatcher.

Also, the user’s location can be a key piece of information for a lot of mobile apps. With traditional mobile apps, as long as the user grants permission, the app can access the user’s current location. This persistent access to location is not available to most chatbot developers yet. On Facebook Messenger the chatbot can request the user’s location, but it must do so each time it needs it. This is a big deal for Hayfever. Location is critical to look up the allergens in the area when a user logs symptoms. No direct access to location is the strongest argument against converting Hayfever to a chatbot at this time.

Finally, developing a chatbot app requires a different skill set than a traditional mobile app. I found myself spending more time writing copy than I ever have for an app. One essentially has to write a script, which is not something most developers are comfortable doing. Also, the tools for writing, editing, and testing chatbot interactions are hard to find. I will write a follow up post about the tools I used to create the chatbot.

What a Chatbot Can Do Well

When a technology gets a lot of hype, eager developers will try to use that technology to solve every type of problem. These are still early times for conversational user interfaces. We haven’t really seen best practices emerge yet. But there are several things that conversational UI’s can do very well and are a great fit for an app like Hayfever.

In the past I have used several apps to log information like what I’m eating, what workouts I’m doing, or how I’m feeling. My experience with most of these is that interaction with the GUI can be tedious and dry. This means I get bored and stop logging. A conversational UI can add a little personality to an otherwise bland interaction. Instead of checking boxes on a form, I can get the feeling of discussing my symptoms with a sympathetic friend or doctor. A chatbot can express concern on days when my symptoms are bad, offer advice or remedies, and convey happiness when my symptoms subside.

A GUI also has the challenge of displaying a large number of possible options on the screen. This can be overwhelming and distracting for users. I acknowledge that a more talented designer could do a much better job than I in laying out the data entry form and hiding unnecessary features. But that’s definitely an art and not a trivial skill. With a conversational UI it’s easier to surface only the questions relevant based on the current user’s history and progression through the conversation. This is a balancing act because leading a user through endless yes/no questions is not a good experience either. I’ve found that once Hayfever knows a little bit about my symptom history, things don’t change too much and logging becomes pleasant.

Finally, chatbots can handle re-engagement very naturally. With Hayfever, knowing that someone is not experiencing symptoms is as valuable as knowing that they are. But when someone is symptom-free, logging is not top of mind. A chatbot can send a natural language prompt like, “Yesterday you reported mild allergy symptoms. Are you still sneezing?” Traditional apps can do this with push notifications, but not without added complexity. First, your user must allow the push notification to come through. Second, the app must navigate to the correct point in the data entry flow when the user taps the notification. With a chatbot, the user drops directly into that point in the conversation after opening the messaging client.

Summing Up

For the last few months I have been looking for a way to get better adoption on an app I wrote to let people log and analyze allergy symptoms. I reviewed data showing that users are not installing new apps often on their phones. Some of the top apps that are being installed are messaging apps. So I converted Hayfever into a chatbot on Facebook Messenger. I discovered that creating a chatbot required me to use some different skills, copywriting in particular. I also found that chatbots are not ideal for use cases that rely on a user’s current location. But a conversational user interface was able to simplify repeated data entry. It also made logging information more engaging. I will find out during this allergy season if the chatbot version of Hayfever gets more usage than the app version.

If you liked this and want me to write more about my chatbot experiences, click the? below.