I know sentences. In my decade as a print journalist, I’ve written hundreds of articles for dozens of publications. I’ve dished out more sentences than Judge Judy. But I didn’t study writing or journalism, at least not formally.

My degree is in electrical engineering. I learned to write by studying, and imitating, the sentences of professional writers. And writers are at their best, generally, in their first and last sentences.

“The most important sentence in any article is the first one.

You should give as much thought to choosing your last sentence as you did your first.”

— On Writing Well, William Zinsser

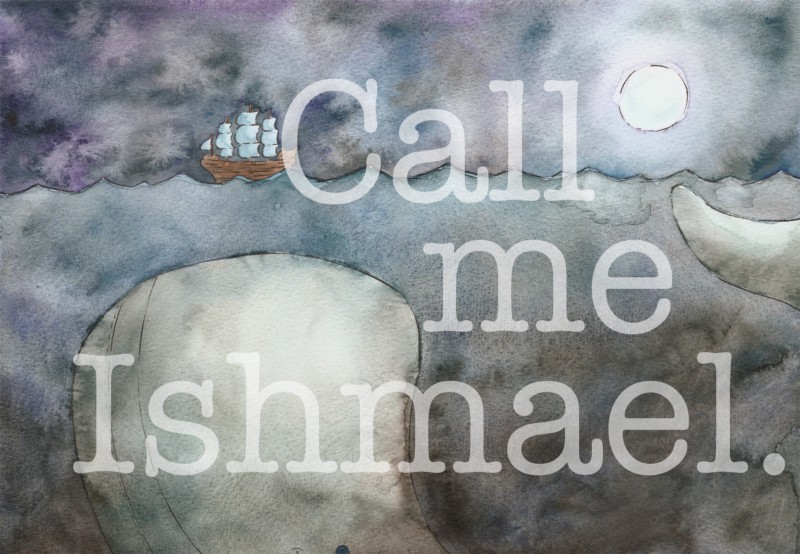

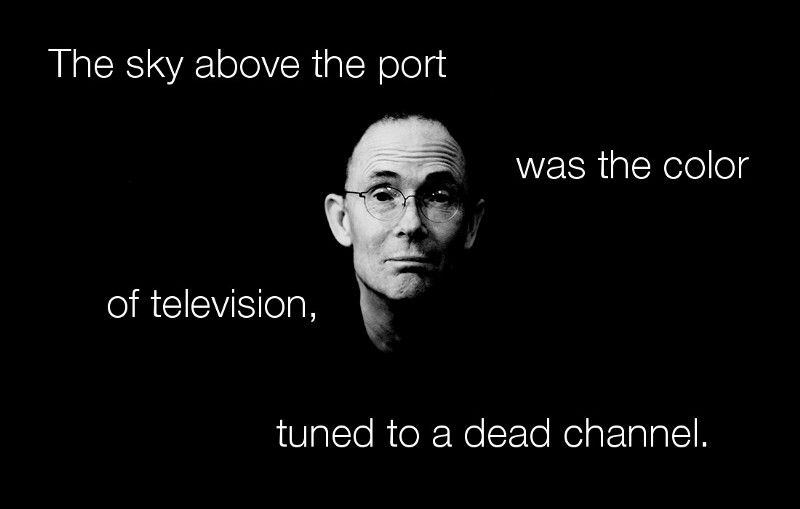

One way to get a feel for how to construct good sentences is to type out the prose of writers you admire while reading it aloud. Hunter S. Thompson copied entire novels, punching The Great Gatsby and A Farewell to Arms into his typewriter to get Fitzgerald and Hemingway into his fingers.

I haven’t done anything that extreme, but I have, for many years, typed out the first and last sentences of every book I read, which has resulted in an ever-growing list and, I hope, improvements to my own writing.

But I can read only so many books and log only so many sentences in the few hours I have each day between earning $’s and catching Z’s. Kids to raise, rugs to vacuum, Stranger Things to binge — you know, life.

Wouldn’t it be great, I’ve often thought, if there were a place online where anyone could contribute the first and last sentences of the books they were reading. We could, together, build a treasure trove of sentences. It would be a great resource for people who, like me, enjoy learning by imitation.

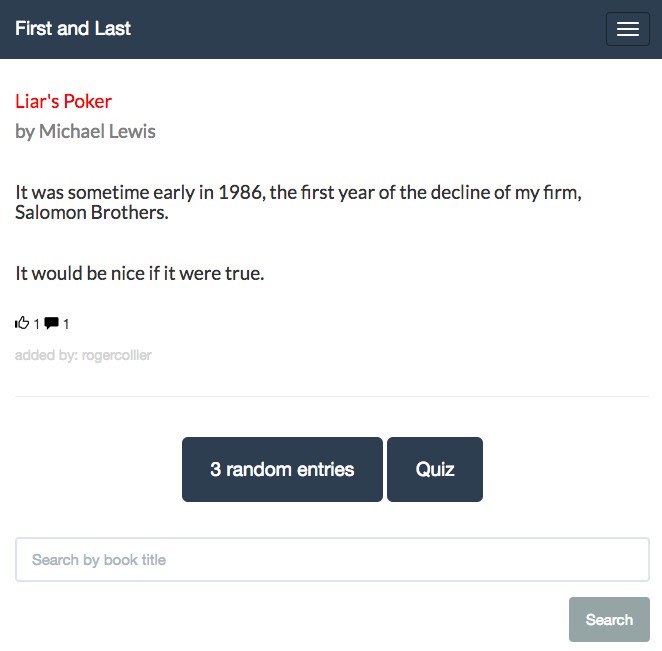

Well, it just so happens that my latest obsession is learning to program in JavaScript. So I have begun, with my limited knowledge, to make that place myself, using the JavaScript frameworks MongoDB, Express, Angular 2, and Node.js — known, collectively, as the MEAN stack. I’ve called this (very simple) web application First and Last.

“Some appreciate fine art; others appreciate fine wines. I appreciate fine sentences.”

— How to Write a Sentence and How to Read One, Stanley Fish

The rest of this post will alternate between sections describing more of my thoughts on how to write better sentences and sections explaining some of what I learned about programming while working on First and Last.

If you are interested only in writing, feel free to skip the sections on programming. If are interest only in programming, you can scroll past the parts on writing. If you are interested only in ironing your underpants while skydiving or mountain climbing, please go here instead.

Read everything

If you aspire to be a literary star — the next Jonathan Franzen or Zadie Smith — then stick to reading highbrow literature. Learn from the masters. But most people who want to improve their writing have more modest goals.

“Every book you pick up has its own lesson or lessons, and quite often the bad books have more to teach than the good ones.”

— On Writing, Stephen King

Perhaps you want to start a blog or write a Medium post for Free Code Camp. Maybe you want to impress your boss by writing better reports.

In my city — Ottawa, Ontario — about 150,000 people work for the Canadian federal government. Thousands more are employed by the city. The most frequently produced pieces of writing here, I reckon, are government documents: memos, briefing notes, regulations, media releases, policies, public advisories, guidelines, and so on.

Are most of these documents written well? Ah, let’s just say there’s room for improvement. Lots of room. Canada-size room.

People who simply want to write more clearly and concisely may find greater benefit in studying sentences outside the realm of literary fiction. Read popular nonfiction. Read children’s books. Heck, read cereal boxes.

A good place to find sturdy, workmanlike sentences is in the work of genre novelists, the authors who deal in hardscrabble detectives, spurned lovers, clever lawyers, and dreamy vampires.

Yes, these books are often rife with cliches. But they are never confusing. Authors like James Patterson, Linwood Barclay, and Harlan Coben are experts in making sentences go down easy. I’ve learned plenty from studying their writing — I’m no book snob — and you’ll find some of their sentences in First and Last.

“If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.”

— 10 rules of writing, Elmore Leonard

The sentences in commercial fiction are spare and straightforward. They contain few flourishes, no hooptedoodle. People bring these books on beach vacations for a reason. You can read them while half-drunk and not miss anything.

It is ill-advised, on the other hand, to tackle Ulysses after your fifth Bahama Mama.

Not enough info

My main technical goal in making First and Last was simple: grab data from the browser, stick it in a database, then get it back to the browser to display. That’s pretty much it. I wanted to learn how information moves between the front end (Angular) and the back end (Node and MongoDB).

In other words, I wanted to make an app that performed the four basic database operations — create, read, update and delete (CRUD). I’m no fan of acronyms, but I must admit, I like CRUD and MEAN. Them’s sweet words to this surly pessimist.

Step 1: Get user input

Step 2: Store in MongoDB

Step 3: Fetch from database and display in browser

Like I said, simple. No fancy algorithms. No data visualization. Just moving information, mostly text, back and forth. Still, I made one silly assumption that caused me some trouble.

To display my stored sentences in the browser, I first had to fetch them from the database. When I asked MongoDB for three random entries, it returned an array with three objects. In Angular, I assigned the fetched data to a local array called “sentences,” which I declared as containing objects.

export class DisplayallComponent implements OnInit {

sentences: [Object];

That worked fine. Later, I decided to allow users to “like” and comment on sentences. So I had to update, in the back end, the data schema that told MongoDB what type of information to store. I declared a like counter as a number and an array of strings called “likedBy,” where I put the usernames of users who had liked a particular pair of sentences.

const SentenceSchema = mongoose.Schema({

likes: {

type: Number, default: 0

},

likedBy: {

type: [String]

}Again, no problems. Finally, I added comments. Each comment object would contain a username and the body of the comment. I added an array of objects to my data schema, declaring it the same way I had done for my “sentences” array in Angular.

const SentenceSchema = mongoose.Schema({

likes: {

type: Number, default: 0

},

likedBy: {

type: [String]

},

comments: {

type: [Object]

} When I tested commenting, though, it didn’t work. There were no obvious errors on the front end, no red text screaming at me in the console of Chrome DevTools. When I peeked in the database, however, the comments I had submitted in the browser were nowhere to be found.

After a bit of try-this-try-that and some quiet late-night cursing, I figured out the problem. MongoDB, it turned out, wanted me to be more specific than Angular. I had to tell it the data types of each element in a comment object in my “comments” array. Just stating that the array contained objects wasn’t good enough.

comments: [{

username: String,

body: String

}],Programmers, it would seem, have at least one thing in common with the author of Fifty Shades of Grey. Sometimes it pays to be more explicit.

Keep it short(ish)

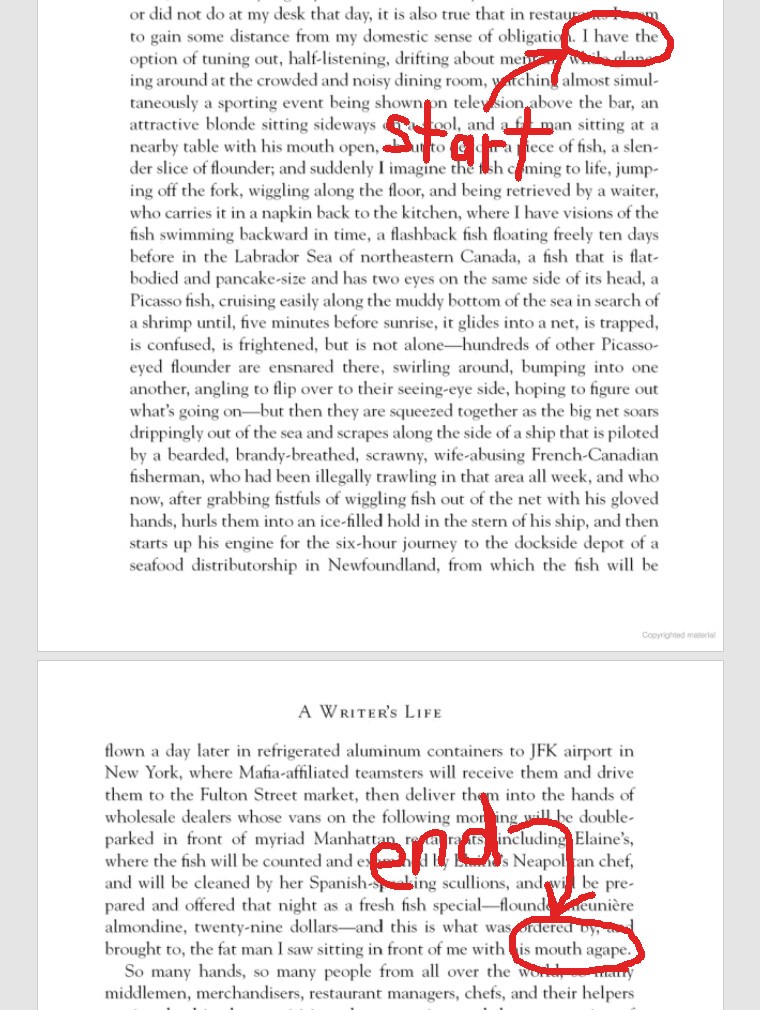

I love a good long sentence, I really do. Garrison Keillor, of A Prairie Home Companion fame, writes beautiful, funny, rambling sentences that end only when the ink runs out. Novelist E.L. Doctorow starts Billy Bathgate with a 131-word sentence and ends with a 277-word whopper. In A Writer’s Life, nonfiction legend Gay Talese has a sentence that is FOUR HUNDRED AND NINETEEN words long.

But make no mistake — these writers are showing off. They are good at what they do and want you to know it. And that’s fine by me. Because in the hands of a great writer, any sentence, even one longer than Shaquille O’Neal’s Burger King receipt, will be under control.

I’m no Gay Talese. Neither are you. If you go long, you will go wrong. Trust me. I edit the writing of freelance journalists and academics, and when the clauses start to pile up, so do the problems. Dangling modifiers. Mismatched pronouns. Inelegant repetition. Unnecessary words. Funky conjunctions.

In short, blerg.

It is best to vary the length of your sentences — it’s more pleasing to the ear — but keep them in check. A mixture of short and medium-length sentences is your safest bet.

Too much info

I’m about to share more code, and things are going to get ugly. Sorry, I’m new to this. If you would like to mock me in the comments, feel free.

Journalists have thick skin. We need it. Earlier this week, for example, I received the following email — from some guy who rents luxury apartments in Budapest — about an article on intermittent fasting I wrote in 2013.

Anyway, this was the function called in Angular when a user clicked on the thumbs-up icon under an entry in First and Last, as I originally wrote it.

if(this.authService.loggedIn()) {

const isInArray = sentence.likedBy.includes(this.username);

if(!isInArray) {

sentence.likedBy.push(this.username);

this.authService.incrementLikes(sentence).subscribe(data => {

this.sentences[index] = data;Users could “like” a pair of sentences only if they were logged in and hadn’t already “liked” that entry. When those conditions were met, a local array of the users who had liked that pair of sentences was updated.

Then a call was made to update the like counter and “likedBy” array in the database. The entire sentence object was sent to the back end and, when the updated sentence object was returned, the like counter displayed in the browser increased by one.

In my data model in the back end, I had this, sadly.

module.exports.incrementLikes = function(sentence, callback) {

const query = {_id:sentence._id};

sentence.likes++;

const likesPlus = sentence.likes;

const likesUserArray = sentence.likedBy;

const newLikeUser = likesUserArray[likesUserArray.length - 1];

Sentences.findOneAndUpdate(query,

{likes: likesPlus, $push:{likedBy: newLikeUser}},

{new: true}, callback

);

}This function incremented the counter passed in as a parameter and assigned it to a local variable, which replaced the like counter in the database.

If that weren’t round-a-bout enough, I copied the entire “likedBy” array from the sentence object passed to the function, then made ANOTHER local variable to hold the last username in that array before, finally, pushing that username into the database’s “likedBy” array.

It worked, but still. Ridiculous.

The only information MongoDB needed from Angular was the unique ID of the sentence object to update and the username of the user who clicked the thumbs-up icon. Not the whole sentence object.

So, instead, I created a new object with only those two elements in Angular to pass to the back-end.

onLikeClick(sentence, index) {

if(this.authService.loggedIn()) {

const isInArray = sentence.likedBy.includes(this.username);

if(!isInArray) {

const updateLikes = {

likeID: sentence._id,

likeUsername: this.username

}

this.authService.incrementLikes(updateLikes).subscribe(data =>

this.sentences[index] = data;Then I simply incremented the like counter inside the database (rather than incrementing outside and overwriting the database value) and pushed the username passed to the function into the database’s “likedBy” array.

module.exports.incrementLikes = function(updateLikes, callback) {

const query = {_id:updateLikes.likeID};

const newLikeUser = updateLikes.likeUsername;

Sentences.findOneAndUpdate(query,

{$inc: {likes: 1}, $push: {likedBy: newLikeUser}},

{new: true}, callback

);

}When you’re a newbie to programming, the joy of making something work can cloud judgment. It’s tempting to leave ugly code alone because, after all, it does what I want it to do. But if I value concision when I write prose, why should it be any different when I write code? Clutter is clutter.

No point in passing around information that isn’t required.

When a police officer asks for your driver’s license, you don’t also hand over your library card, birth certificate and Ashley Madison password.

Keep it simple

I’m a huge fan of readability. I think when you glance at a dense paragraph of long sentences — riddled with acronyms or statistics or symbols or puffy job titles or long, awful words ending in “-ization” — your brain sighs.

“Oh, how wonderful,” it moans with its wee brain-mouth. “This is gonna be hella fun.”

Many people who write occasionally as part of their jobs, academics and subject experts in particular, are so concerned with content that they often fail to consider presentation. They want to be comprehensive, to make all their points — point A to point Z — and will stuff as much information as possible into every sentence.

But if the end result is unreadable and unlikely to be retained, perhaps there’s no point at all. I’d prefer readers to remember a few ideas presented clearly than instantly forget a dozen over-stuffed ideas presented haphazardly.

“Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words? He thinks I don’t know the ten-dollar words. I know them all right. But there are older and simpler and better words, and those are the ones I use.”

— Ernest Hemingway

There will always be unsightly clutter in some forms of writing — it’s unavoidable. Articles on programming and technology will have acronyms. Business writing will have buzzwords. Summaries of medical research may contain adjusted rate ratios of 0.86, 96% CI 0.4–0.56.

Still, we can try to do better. We can present only the information the reader needs, nothing more. We can resist the urge to impress, to show off our Google-enhanced vocabularies. We can trim decorative adjectives, eschew jargon, avoid “whom” at all costs. We can do more than just dump words on a page.

Writing well is difficult. But it is the writer who should suffer. Not the reader.