Popular guides like YouMightNotNeedJQuery.com and You Don’t Need Lodash/Underscore have challenged common industry practices.

This post is not as wild as, say, YouMightNotNeedJS.com, but it does elaborate on transpilation, and explains why it may not be as necessary in the near future.

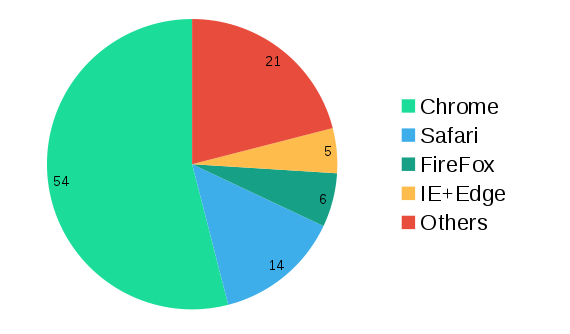

StatCounter gathers data about 15+ billion page views every month from 2.5 million websites around the globe. As of May 2017, this is the status quo:

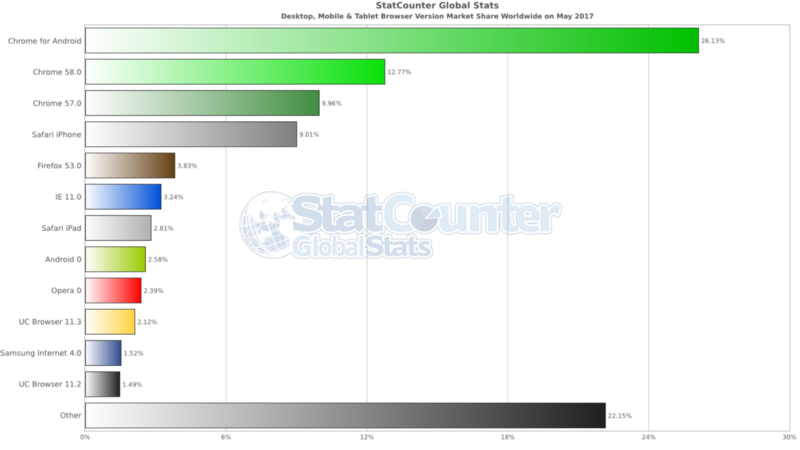

The thing that makes this diagram interesting is that the top 3 browsers (Chrome, Safari and FireFox) are evergreen, which means 74% of users get the latest version of their browser automatically.

Let’s see whether this assumption is correct.

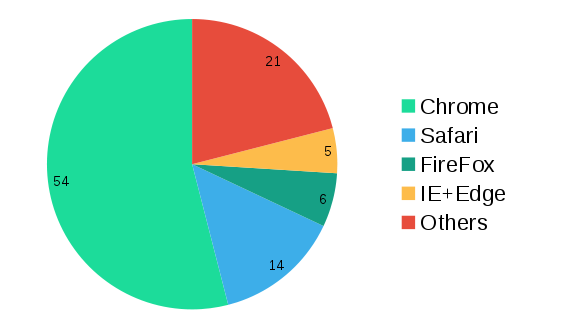

Here are the top browser versions in the market:

Chrome 58 was released less than a month ago and its desktop version holds 12.77% of the global browser market share. Chrome 57 was release just 42 days before that and its desktop version holds 9.96% of the global browser market. Unfortunately StatCounter doesn’t differentiate between chrome versions on mobile platforms but assuming the same ratio as desktop we end up with:

What does it mean for my code?

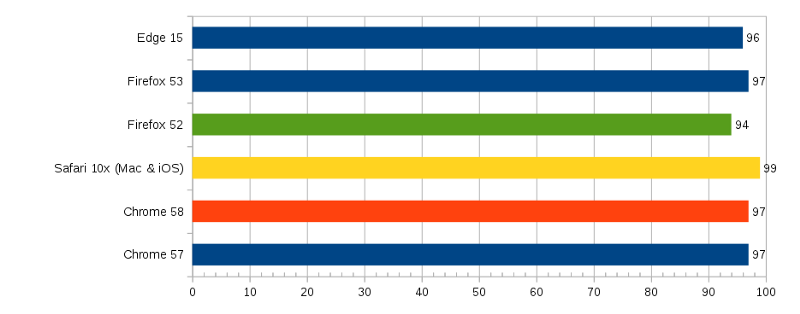

According to ES Compatibility Table the latest version of all major browsers have a very good support for ES6 features:

In other words if you’re transpiling your JavaScript to ES5, you’re making your code unnecessarily big and slow to support a minority of the users who will probably upgrade their system by the time you manage to configure your Webpack and Babel! ?

Why would you still transpile?

You may still want to transpile your code but hopefully after weighing cons and pros or possible alternatives:

- You’re using React JSX (which is pretty popular at the moment so I’m assuming lots of developers fit into this category). JSX at its core is a transformation of XHTML to JS code and doesn’t necessary need a full transpiler like Babel. Besides, if all you need is VirtualDom, use that instead.

- You want to try the latest features of the language. Unless you’re part of TC39 or have a burning desire for injecting unstable language features into your production code, you’re probably fine with ES6. Nowadays we have a decent language is the majority of the browsers and the need to transpile are fading away.

- You’re using TypeScript and hopefully weighed the cons and pros. TypeScript compiler, when targetting a modern version of ES6 mostly strips out the type information rather than transforming syntax.

- You wanna reduce code size using tree shaking (here’s is how to do it in webpack and rollup). You want to obfuscate your code or reduce its size by minification. You want to conditionally exclude part of the code. This requires static code analysis. You can use a smart bundler for size-sensitive production services like Mobile devices, but we’re gonna see more careful cost assessments when creating such alternative deployments. These sorts of static code analysis will continue to be useful as “advanced optimization techniques” for production code. You don’t have to minify your files. UglifyJS can’t minify ES6 at the moment (though a harmoney branch exists) but Babili can deal with it. The compression algorithms do a pretty decent job (not when the files are too little) and unless you’re shipping an operating system in every page load, it should do fine without compression. These days images and multimedia content take much more bandwidth than the code.

- You want the elephant in the room:

NPM is the largest package manager on the planet. Most non-trivial web applications use some code from NPM and that implies using a module bundler. That is soon gonna change! Chrome already supports ES6 modules in Canary (Chrome 60 will officially ship this feature this August) and Safari is close to ship it too while Firefox and Edge are working on it.

Besides HTTP/2 allows voluntarily pushing resources to the browser. That means if a.js is importing b.js and c.js, the server can push b.js and c.js every time a.js is fetched which minimizes the time between requests. This is of course a simplified view because in practice browser might already have b.js and c.js in its cache. HTTP/2 is supported in the majority of browsers.

The future without Transpilation

Considering the statistics above, this means 2018 will be the year the majority of the web apps can get rid of the module bundlers or transpilers.

Transpilation is a workaround. We might have done it for too long that we got used to it, but think about it. We are “compiling” an “interpreted” language to an “interpreted” language! Besides:

- Configuring Webpack/Browserify is an unnecessary tax in many cases

- Debugging using sourcemaps is always harder than debugging the actual script being run (anyone had fun trying to debug

thisor variables when sourcemaps don’t work properly?) - It kills the DX when you have to wait a few seconds (sometimes half a minute) after each edit to see the latest code. Hot Module Reloading (HMR) is an answer to that but it’s not always smooth and quick to configure. Without transpilation, all you have to do is to refresh the page and in less than a second your latest page is there!

This August when ES6 modules are shipped, some types of applications will not use transpilation at all:

- Chrome Extensions

- Electron desktop applications

- B2B web apps that are made to be run by business users who already have good gears provided by the company

When transpilation becomes a thing of the past, libraries with Hyperscript syntax will bring the ideas of React to POJS (Plain Old JavaScript that is not transpiled and easily debuggable on the console).

Don’t transpile, but compile for real!

WASM is the new kid in town and it’s the official compilation target that promises faster execution speed and smaller code size. Currently Chrome and Firefox support WASM but there’s a good consensus among the big browser vendors that WASM is going to be the common run-time of the future. If you got Chrome, you can give it a try.

If you’re the kind of developer who itches for something new, take a look at Rust. It compiles to WASM but isn’t limited to web. People actually use it to write operating system or browser engine. Besides old time C/C++ developers approve and like it and it has a very welcoming community.

A few notes

- According to former Mozilla CTO Chrome won and it’s unlikely that there’s going to be another browser war. The interesting thing is that Chrome won it with meritocracy. It’s open source and Google has clearly defined what information it is gathering from the users. Chrome wins even the business users which traditionally use Windows. Nevertheless, while the end users choose Chrome because of its speed, security and simplicity, programmers love its developer tools. Google have an active role in the TC39 which drives the future of JavaScript and in general is the strongest proponent of the web platform even though it may compete with its own mobile OS. Not only that, but Google also helps its competitors. Google has been one of the biggest financial supporters of Mozilla and its rendering engine is used by Opera.

- Microsoft officially dropped support for IE about 17 months ago. IE 11 will continue to receive security updates until 2025, but it’s up to you to decide on spending significant resources to support a browser that only 3.24% of the market uses. Also keep in mind that Edge is the default browser in Windows 10. If anyone doesn’t want to upgrade their Windows to the latest version, the recent WannaCrypt attack probably gives them a reason to reconsider! I’m personally interested to any market research on the revenue coming from this particular customer segment.

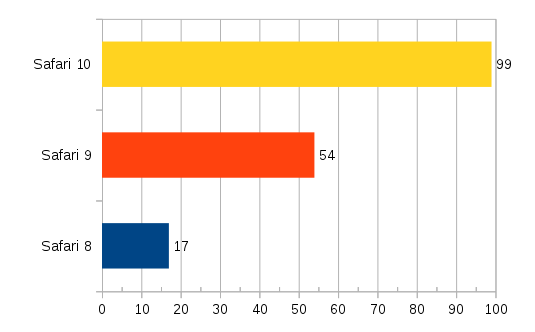

- Apple put a set of unfair restrictions to keep the other browser vendors out of their iOS platform. So for example Chrome on iOS is technically limited to parts of Safari engine! Safari used to be the new IE, until back in 2016 they did a good job and became the browser with the best ES6 support:

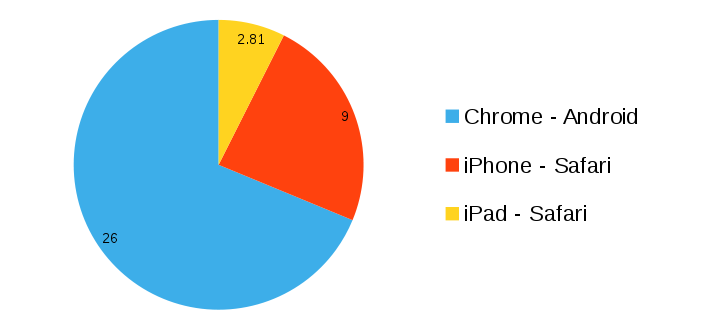

Overall the global share of iOS/Safari is less than Android/Chrome. It varies by country, for example in richer countries iOS has a bit higher penetration while in the developing world Android is the absolute winner but globally here are the stats:

Call to Action!

If you’re old enough, you probably may remember the annoying days when some websites forced (or politely suggested) their browser of choice (mostly IE):

We don’t wanna do that! No matter how excited we are about Chrome, we don’t want to ignore 46% of the web traffic not being rendered by Chrome.

Just because we might have support for ES6 modules in browsers soon, it doesn’t mean that we can get rid of a build process and a proper “bundle strategy”. — Stefan Judis

We’ll always have people stuck with an old browser in their TV firmware or car infotainment system. We’ll always have that stubborn grandpa who doesn’t see the need to invest in upgrading his machine only to leave it as a legacy. Kids will continue using their parent’s old iPhone or tablet and 1 laptop per child will not grow some processing power over night. We don’t want to lock anyone out.

This is not a new problem though. Despite ES6 being one of the biggest changes in the web, graceful degradation can still provide some use for the minority while keeping the development costs under control for the majority.

In a future post I’ll discuss the practical side of how to ship modern code while having a backup plan for graceful degradation. You can follow me on Twitter or Medium to stay tuned.

BONUS: Take a look at JS Codeshift. It is a CLI for converting old javascript code to new javascript code updating even old javascript library calls to their latest API. It tries to preserve as much as the original styling as possible. Workflow: after committing your changes to version control, run this and do a thorough comparison and run the automated & manual tests. Done!

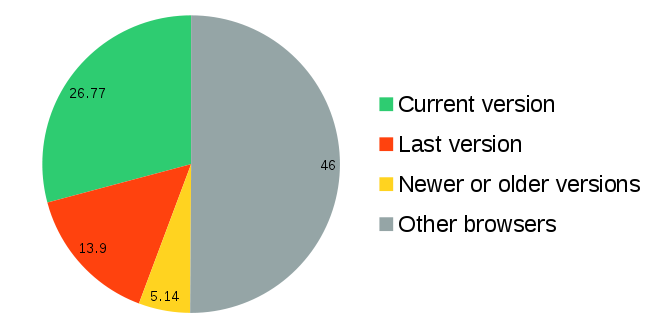

Update 1 (2017–09–8): Chrome 61 landed a few days ago with full ES6 module support. It has 54% of global browser market. Safari (14% of global market) has supported ES6 modules for a while.

Update 2 (2017–09–10): you can still support browsers which don’t support ES6 modules thanks to this trick <script nomodule src=”compiled.js”><;/script>. The nomodule attribute tells the browsers with ES6 module support not to load the script. On Safari there are some caveats that you can read in the page that talks about the trick. Read the spec.

Update 3 (2017–09–12): ES6 modules support lands in browsers: is it time to rethink bundling?

Update 4 (2017–09–12): module are deferred by default. If you want to bypass that, add an async attribute to the script tag to prevent Single Point Of Failure (SPOF).

Update 5 (2017–09–13): Node LTS 8.5 supports ES6 Modules (called ESM) behind a flag when the file has a *.msj extention. Here’s a nice intro about how they’re used.

Update 6 (2017-09–22): here is some great practical advice for supporting both new and old browsers. The bandwidth savings for avoiding transpilation is great!

Update 7 (2018–01–15): Lebab (the reverse of Babel) is has a CLI for modernizing old-style Javascript. This is a bit similar to Facebook’s CodeShift because they both modernize old code.

The most widely deployed bug in the history of computing opened up a great opportunity for us! Read Why we should convince our users to update their browsers?