For the longest time, the evolution of cooperative social behaviour has fascinated evolutionary biologists.

The mathematical field of game theory helps shed light on how it emerges. Game theory is “the study of mathematical models of strategic interaction among rational decision-makers” (according to Wikipedia).

Game theory applies to “games” as varied as economics, politics, chess and tic-tac-toe. In each case, there are some rules, some “players” or “agents”, and a set of strategies available to them.

Each player has a concept of “utility” – a “currency” they seek to individually maximise through the strategies they play.

The currency of evolution is the concept of fitness.

That is, the chance of being represented in the next generation. Genes and traits which increase the odds of survival to reproductive age are more likely to be passed on to future generations. Therefore, they confer a greater fitness to the individual which "hosts” them.

Evolutionary game theory takes the concepts from game theory and applies them in an evolutionary context.

For a given model, it lets you ask questions about which strategy prevails, and whether certain strategies can coexist. And if so – at what frequencies?

Replicator dynamics

Evolutionary game theory plays “games” over many generations.

Each game will alter the utility (that is, fitness) of the players. The next generation is produced, with players being represented proportionally to their overall fitness.

This set up is called “replicator dynamics”. It is easy to simulate and explore different models of evolutionary games.

The classic model of evolutionary game theory is the “Hawk-Dove” game, popularised by John Maynard Smith in the 1970s.

In this game, there exists a population of animals which compete for a finite resource (for example, food). The more resources an individual wins, the greater its fitness.

Each animal can play one of two strategies:

- Hawks are aggressive, and will fight for a resource at all costs.

- Doves are passive, and will share instead of fight for a resource.

The animals are all the same kind – “hawk” and “dove” refer to their behaviour.

There are three pairwise competitions that can exist:

Hawk vs Hawk

- If two hawks compete, they will engage in a 50:50 battle to win the resource. This is a winner-takes-all scenario – the winner obtains the full value of the resource. The injured loser pays a price, and loses a certain amount of fitness.

Hawk vs Dove

- If a hawk meets a dove, the dove will back down immediately. The hawk wins the full value of the resource, and the dove walks (or, rather flies) away with nothing. But they do not pay any cost.

Dove vs Dove

- When two doves meet, they agree to share the resource evenly. No one gets hurt.

This can be modelled mathematically. Doing so allows us to understand whether these strategies can coexist (or if one of them prevails).

The math of replicator dynamics

Let V be the value of winning a contest, and C be the cost of injury in a contest.

Represent the frequency of hawks in the population as p, and the frequency of doves as 1-p.

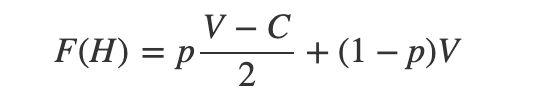

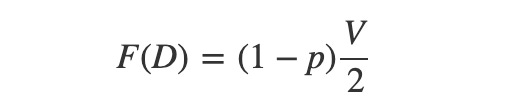

Now, define two functions F(H) and F(D) which define the expected fitness of playing the hawk and dove strategies, respectively.

Playing as a hawk will mean engaging in a hawk-vs-hawk contest with frequency p. The expected utility of doing so is understood as the average outcome. Half the time the hawk wins V, half the time it loses C.

The rest of a hawk’s contests will be against doves. This guarantees an easy win V.

Playing as a dove will win nothing against hawks. But a dove will encounter another dove with frequency 1-p. Under this scenario, the expected utility is the shared resource, worth V/2.

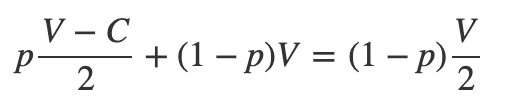

Now, set F(H) equal to F(D) and solve for p.

This reveals the frequency p at which the hawk strategy confers no more or less fitness than the dove strategy.

At this frequency, there is no advantage to either strategy, so this is the equilibrium at which both strategies may coexist.

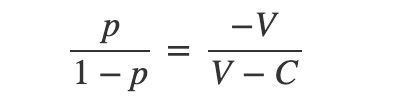

Some algebraic rearrangement gives:

Which provides the ratio of hawks-to-doves that exists at equilibrium.

Just a little more rearranging gives the equilibrium in terms of p:

Considering the properties of this expression reveals two things:

- Whenever the cost C of losing a contest is less than or equal to the value V of winning, the hawk strategy will dominate. Neither strategy can coexist.

- If the cost C is greater than the value V, the strategies will coexist in equilibrium.

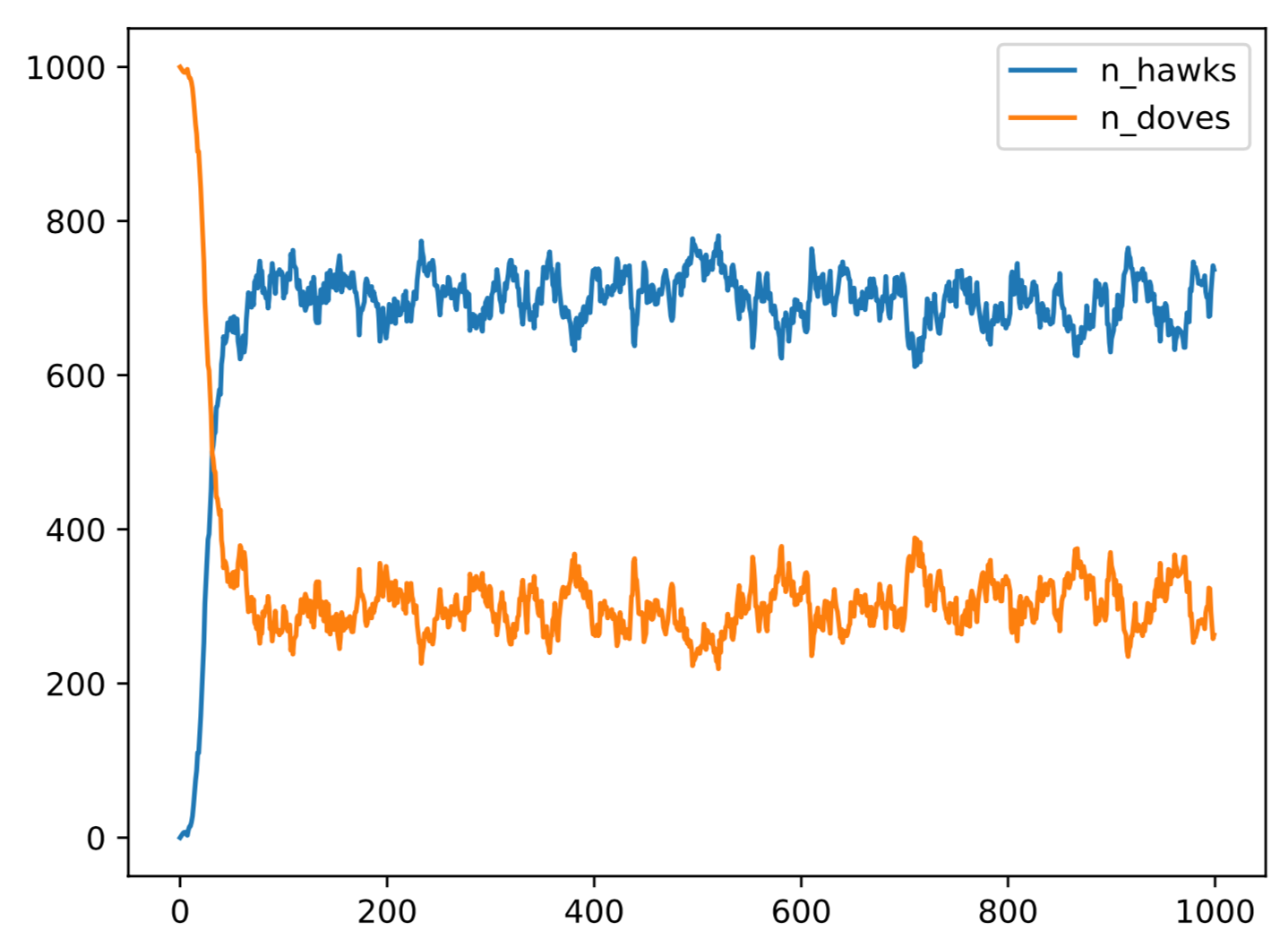

Plugging in the values V=4 and C=6 shows the equilibrium occurs when 2/3 of the population play the hawk strategy.

You can test this by simulating the model in Python.

The code

In the file called bird.py:

import random

class Bird:

def __init__(self, strategy):

"""

Each bird has a strategy type (hawk or dove)

And a small starting fitness

"""

self.strategy = strategy

self.fitness = 10

def contest(self, opponent, v, c):

"""

Simulate the outcomes depending on the strategies

"""

# both hawks --> 50:50 battle

if self.strategy == opponent.strategy == "hawk":

if random.randint(0, 1) == 1:

self.fitness = self.fitness + v

opponent.fitness = opponent.fitness - c

else:

self.fitness = self.fitness - c

opponent.fitness = opponent.fitness + v

# hawk meets dove

elif self.strategy == "hawk" != opponent.strategy:

self.fitness = self.fitness + v

opponent.fitness = opponent.fitness

elif self.strategy == "dove" != opponent.strategy:

self.fitness = self.fitness

opponent.fitness = opponent.fitness + v

# both doves --> share the resource

else:

self.fitness = self.fitness + v/2

opponent.fitness = opponent.fitness + v/2

def spawn(self):

"""

Allow a small chance of mutation to flip strategy

Otherwise, return offspring of the same type

"""

mutation = random.randint(0, 1000) > 999

if mutation:

if self.strategy == "dove":

return Bird("hawk")

else:

return Bird("dove")

else:

return Bird(self.strategy)

The next file is called simulation.py.

- Initialise a population of all doves.

- Define a timestep function to simulate randomised contests.

- Draw the next generation weighted by their relative fitnesses.

- Rinse and repeat a thousand times over, then save the output as a graph.

from bird import Bird

import random

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib

def initialise():

"""

Create a population of birds - all dove to begin

"""

birds = []

for _ in range(1000):

birds.append(Bird("dove"))

return (birds)

def timestep(birds, value, cost):

"""

Pair up the birds, make them compete

Then produce next generation, weighted by fitness

"""

next_generation = []

random.shuffle(birds)

for _ in range(1000):

# pair up random birds to contest

a, b = random.sample(birds, 2)

a.contest(b, value, cost)

# generate next generation

fitnesses = [bird.fitness for bird in birds]

draw = random.choices(birds, k=1000, weights=fitnesses)

next_generation = [bird.spawn() for bird in draw]

return next_generation

def main():

birds = initialise()

rows = []

V = 4 ; C = 6

for _ in range(1000):

# add the counts to a new row

strategy = [bird.strategy for bird in birds]

n_hawks = strategy.count("hawk")

n_doves = strategy.count("dove")

row = {'n_hawks': n_hawks, 'n_doves': n_doves}

rows.append(row)

# run the timestep function

birds = timestep(birds, V, C)

# create dataframe and save output

df = pd.DataFrame(rows)

df.to_csv('simulation.csv')

fig = df.plot(y=["n_hawks", "n_doves"]).get_figure()

fig.savefig('simulation.pdf')

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

And voilà - here’s an example of the output for V=4 and C=6:

Exactly as the theory predicts.

Outro

The evolution of complex systems is a fascinating field of study. Understanding how natural forces and competitive pressures can shape individual-level traits to give rise to complex social behaviours has been one of the major areas of research in biological sciences in the last few decades.

The ability of relatively simple mathematical models to accurately predict outcomes of dynamic systems is also a key point to take away.

In this case, it is the existence of a feedback loop that results in the two strategies reaching an equilibrium. The advantage conferred by either strategy varies depending on how many others in the population are playing that strategy.

In other words, when more individuals play "dove", there is an advantage to playing "hawk". However, as more individuals play "hawk", the expected value of playing "dove" increases.

Finally, the availability of programming and software tools makes it possible to test theoretical predictions through simulation.

If you found this article interesting, you may also find How to Model an Epidemic With R worth checking out, too.

You can follow more of my writing at gleeson.substack.com