Today, we’re going to look at the paper titled “Robustness in Complex Systems” published in 2001 by Steven D. Gribble. All pull quotes and figures are from the paper.

This paper argues that a common design paradigm for systems is fundamentally flawed, resulting in unstable, unpredictable behavior as the complexity of the system grows.

The “common design paradigm” refers to the practice of predicting the environment the system will operate in and its failure modes. The paper states that a system will deal with conditions that weren’t predicted as it becomes more complex, so it should be designed to cope with failure gracefully. The paper explores these ideas with the help of “distributed data structures (DDD), a scalable, cluster-based storage server.”

By their very nature, large systems operate through the complex interaction of many components. This interaction leads to a pervasive coupling of the elements of the system; this coupling may be strong (e.g., packets sent between adjacent routers in a network) or subtle (e.g., synchronization of routing advertisements across a wide area network).

A common characteristic that such large systems exhibit is something known as the Butterfly Effect. This refers to a small unexpected disturbance in the system resulting from the intricate interaction of various components that causes a widespread change.

A common goal for system design is robustness: the ability of a system to operate correctly in various conditions and fail gracefully in an unexpected situation. The paper argues against the common pattern of trying to predict a certain set of operation conditions for the system and architecting it to work well in only those conditions.

It is also effectively impossible to predict all of the perturbations that a system will experience as a result of changes in environmental conditions, such as hardware failures, load bursts, or the introduction of misbehaving software. Given this, we believe that any system that attempts to gain robustness solely through precognition is prone to fragility.

DDS: A Case Study

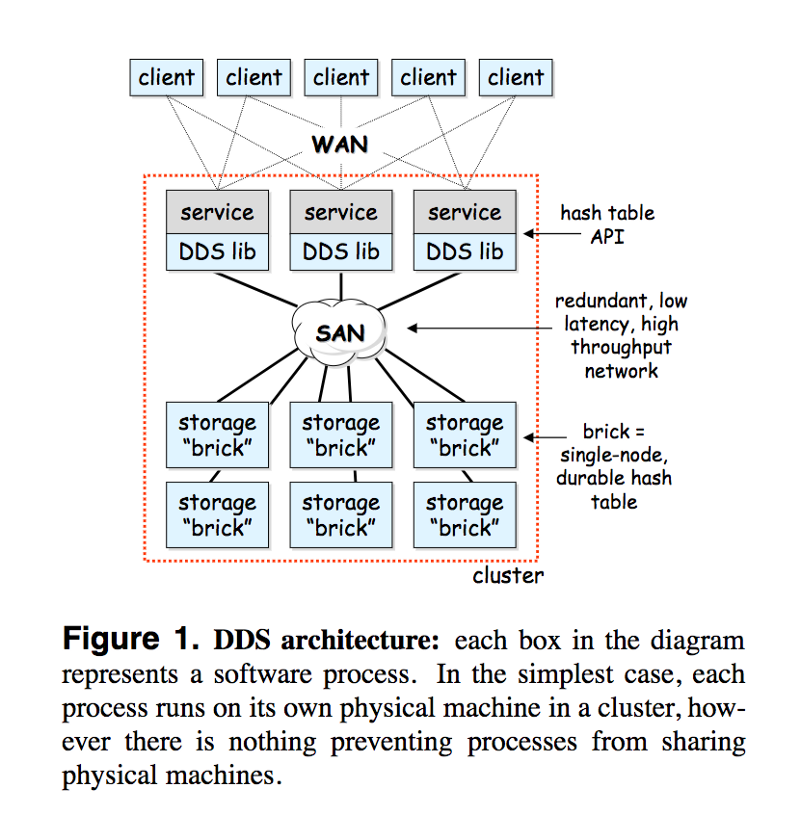

The hypothesis stated above is explored using a scalable, cluster-based storage system, Distributed Data Structures (DDD) — “a high-capacity, high-throughput virtual hash table that is partitioned and replicated across many individual storage nodes called bricks.”

This system was built using a predictive design philosophy as the one described above.

Based on extensive experience with such systems, we attempted to reason about the behavior of the software components, algorithms, protocols, and hardware elements of the system, as well as the workloads it would receive.

When the system operated within the scope of the assumptions made by the designers, it worked fine. They were able to scale it and improve performance. However, in the case when one or more of the assumptions about the operating conditions were violated, the system behaved in unexpected ways resulting in data loss or inconsistencies.

Next, we talk about several such anomalies.

Garbage Collection Thrashing and Bounded Synchrony

The system designers used timeouts to detect failure of components in the system. If a particular component didn’t respond within the specified time, it was considered dead. They assumed bounded synchrony in the system.

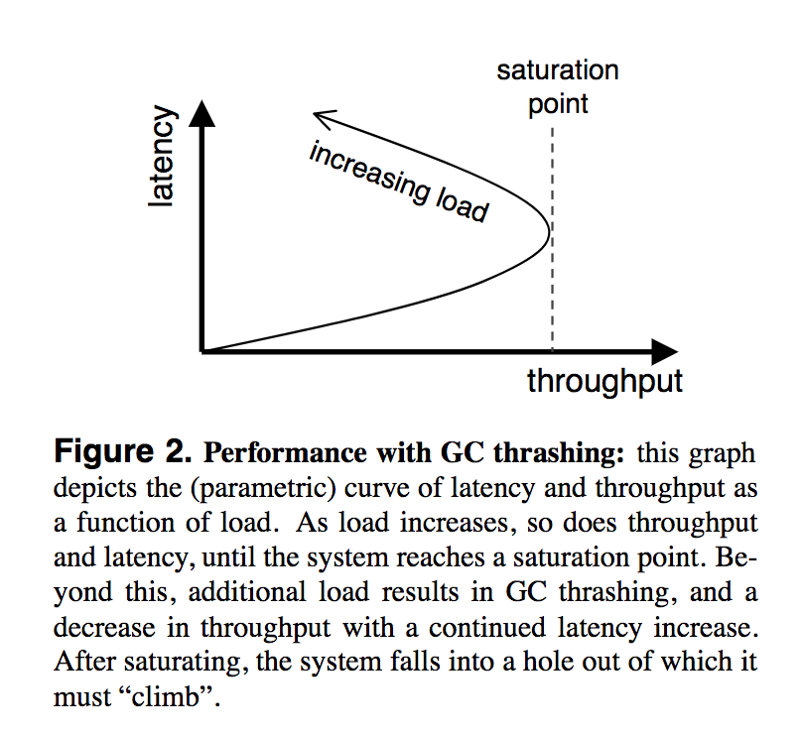

The DDS was implemented in Java, and therefore made use of garbage collection. The garbage collector in our JVM was a mark-and-sweep collector; as a result, as more active objects were resident in the JVM heap, the duration that the garbage collector would run in order to reclaim a fixed amount of memory would increase.

When the system was at saturation, even slight variations in load on the bricks would increase the time taken by the garbage collector in turn dropping the throughput of the brick. This is called GC thrashing. The affected bricks would lag behind their counterparts leading to a further degradation in performance of the system.

Hence, garbage collection violated the assumption of bounded synchrony when it was nearing or beyond the saturation point.

Slow Leaks and Co-related Failure

Another assumption made while designing the system was that the failures are independent. DDS used replication to make the system fault-tolerant. The probability of multiple replicas failing simultaneously was very small.

However, this assumption was violated when they encountered a race condition in their code that caused a memory leak without affecting correctness.

Whenever we launched our system, we would tend to launch all bricks at the same time. Given roughly balanced load across the system, all bricks therefore would run out of heap space at nearly the same time, several days after they were launched. We also speculated that our automatic failover mechanisms exacerbated this situation by increasing the load on a replica after a peer had failed, increase the rate at which the replica leaked memory.

Since all the replicas were subjected to a uniform load without taking performance degradation and other issues into consideration, this created a coupling between the replicas and…

…when combined with a slow memory leak, lead to the violation of our assumption of independent failures, which in turn caused our system to experience unavailability and partial data loss

Unchecked Dependencies and Fail-stop

Based on the assumption that if a component timed out, it has failed, the designers also assumed “fail-stop” failures, that is a component that has failed will not resume functioning after a while. The bricks in the system performed all long-latency work (disk I/O) in an asynchronous way.

However, they failed to notice that some parts of their code made use of blocking function calls. This caused the main event-handling thread to be randomly borrowed leading to bricks seizing inexplicably for a couple of minutes and resuming post.

While this error was due to our own failure to verify the behavior of code we were using, it serves to demonstrate that the low-level interaction between independently built components can have profound implications on the overall behavior of the system. A very subtle change in behavior resulted in the violation of our fail-stop assumption across the entire cluster, which eventually lead to the corruption of data in our system.

Towards Robust Systems

..small changes to a complex, coupled system can result in large, unexpected changes in behavior, possibly taking the system outside of its designers’ expected operating regime.

A few solutions which can help us make more robust systems:

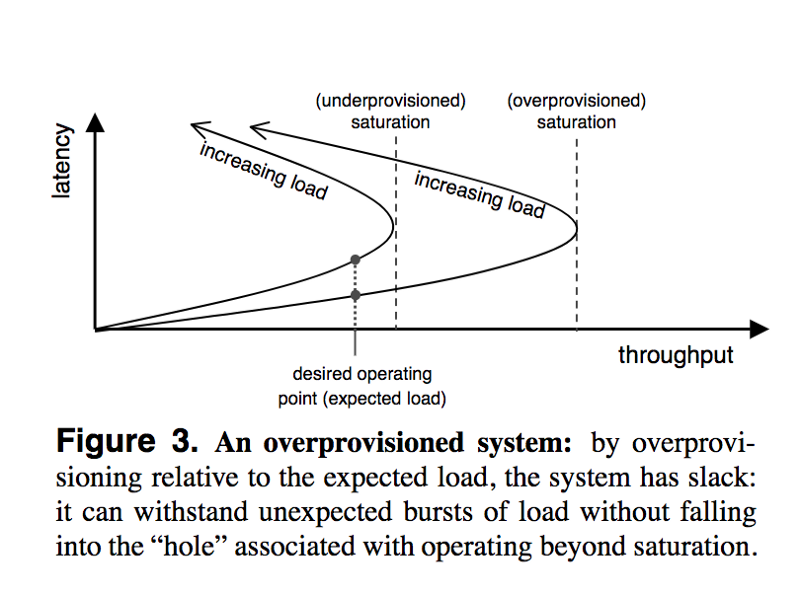

Systematic Over-provisioning

When approaching the saturation point, systems tend to become fragile when trying to accommodate unexpected behavior. One way to combat this is to deliberately over-provision the system.

However, this has its own set of issues: it leads to the under-utilization of resources. It also requires predicting the expected operating environment and hence the saturation point of the system. This can’t be done in an accurate manner in most cases.

Use Admission Control

Another technique is to start rejecting load once the system starts approaching the saturation point. However, this requires predicting the saturation point — something that’s not always possible, especially with large systems which have a lot of contributing variables.

Rejecting requests also consumes some resources from the system. Services designed with admission control in mind usually have two operating modes: normal where the requests are processed and an extremely lightweight mode where they’re rejected.

Build Introspection into the system

an introspective system is one in which the ability to monitor the system is designed in from the beginning.

When a system can be monitored, and designers and operators can derive meaningful measurements about its operation, it’s much more robust than a black-box system. It’s easier to adapt such a system to change in its environment, as well as manage and maintain it.

Introduce adaptivity by closing the control loop

An example of a control loop is human designers and operators adapting the design in response to a change in its operating environment indicated through various measurements. However, the timeline for such a control loop isn’t very predictable. The authors argue that systems should be built with internal control loops.

These systems incorporate the results of introspection, and attempt to adapt control variables dynamically to keep the system operating in a stable or well-performing regime.

All such systems have the property that the component performing the adaptation is able to hypothesize somewhat precisely about the effects of the adaptation; without this ability, the system would be “operating in the dark”, and likely would become unpredictable. A new, interesting approach to hypothesizing about the effects of adaptation is to use statistical machine learning; given this, a system can experiment with changes in order to build up a model of their effects.

Plan for failure

Complex systems must expect failure and plan for it accordingly.

A couple of techniques to do this:

- decoupling of components to contain failures locally

- minimize damage by using robust abstractions such as transactions

- minimize amount of time in failure state (using checkpointing to recover rapidly)

In this paper, the authors argue that designing systems by assuming the constraints and nature of its operation, failures, and behavior often leads to fragile and unpredictable systems. We need a radically different approach to build systems that are more robust in the face of failure.

This different design paradigm is one in which systems are given the best possible chance of stable behavior (through techniques such as over-provisioning, admission control, and introspection), as well as the ability to adapt to unexpected situations (by treating introspection as feedback to a closed control loop). Ultimately, systems must be designed to handle failures gracefully, as complexity seems to lead to an inevitable unpredictability.