by Steve Krouse

Scratch Has a Marketing Problem

At first, I avoided MIT’s Scratch programming language.

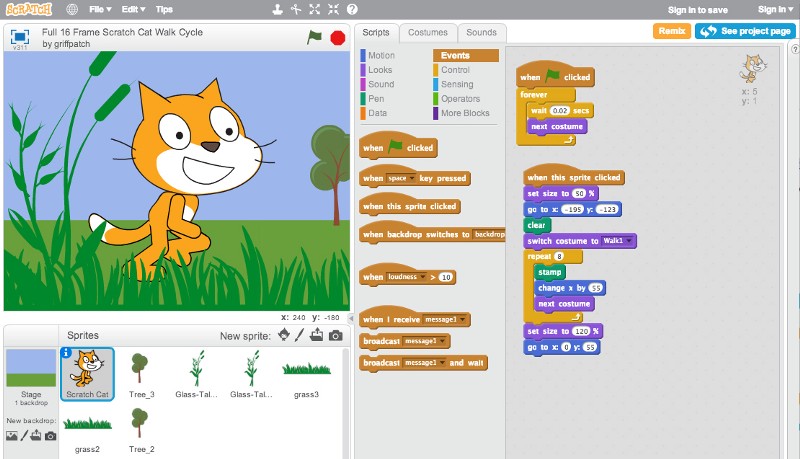

It seems childish. When you load the Scratch homepage, you’re greeted by friendly cartoons that seem appropriate for preschoolers. The programming language itself isn’t even a proper language. Instead of typing, you drag and drop pre-made blocks into place. It’s more reminiscent of LEGO than real engineering.

Every student over the age of 12 seemed to agree with my diagnosis. “I did that in 2nd grade. It’s not real coding.” So I taught students Python, Java, HTML, CSS, and JavaScript — real programming languages that you type, not silly blocks.

However, there was a problem.

It’s hard to teach “real coding.” Really hard. With some students, it seemed impossible.

Before my eyes, the students that were excited to do “real coding,” began to label themselves as “bad at coding” the same way students have learned to label themselves “bad at math.” I felt like I was doing more harm than good, teaching students coding languages they weren’t ready for.

Giving Scratch a Second Look

So I went back to the drawing board, looking for the right programming language for my students. I scoured the Internet for books and tips on how to teach kids to code and everywhere I looked, there was Scratch. So I gave Scratch a try.

It turns out, typing is overrated. Programming isn’t like English. There aren’t a million different words, phrases, and sentence structures. There are only a few dozen, so creating blocks for them saves time, and more importantly, prevents 70% of errors new programmers face. In text-based coding, if you forget a semicolon, your program might not even run, but Scratch won’t even let you make that mistake. Block-based programming enables beginner programmers to focus 100% of their mental energy on the design and logic of their programs, not the semantics.

Even better, Scratch was designed to create video games and stories. Students enjoy making video games almost as much as they love playing them. This means that you don’t have to motivate students with the carrot and stick approach of homework, grades, and tests to use Scratch. It’s intrinsically motivating to make something that you can immediately share with your friends and family, so students continue to work on Scratch projects at home simply for the fun of it.

After this revelation, I was excited to share Scratch with the world, “Hey everyone! The search for the best first programming language is over. We’ve found it!”

Scratch Seems Too Easy

As it turns out, I was late to the party. Everyone already knew about Scratch. Even worse, they actively avoided it because it’s “babyish.”

“No! You don’t understand,” I pleaded with students. “It’s actually really challenging. There’s a lot for you to learn in it before you’ll be ready for JavaScript.” But nobody wanted to hear it.

Last month, this brought a 12-year-old boy to tears in my class.

Sam represented himself as a true nerd, proudly telling the class he memorized over 150 digits of pi, and has been to many technology and science camps. When I suggested he start in Scratch, he shrugged.

“It’ll probably be too easy for me. I haven’t done it since I was in 3rd grade.”

“Just give it a shot,” I said. “If it’s too easy, we’ll move you to JavaScript.”

Ten minutes later Sam was crying. As I walked with him out of the classroom, I asked what was wrong.

“I’m terrible at this,” Sam shook his head. “I can’t do it.”

“Why do you think you can’t do it?” I asked, “It’s only been a few minutes.”

“Scratch is supposed to be easy and I couldn’t even do the first step.” Sam sighed heavily. “I really thought I was good at this.”

“I know it looks easy,” I said. “But Scratch is actually really hard. You can do incredibly complex stuff with it.”

“But, but, but…” Sam sobbed, looking hurt, “But why would they make it look so easy then? They make it look like it’s for babies!”

Scratch Has a Marketing Problem

Everywhere they look, students get the impression that Scratch was designed for young children and is easy. While this does a great job of making it seem inviting for younger students, it has a perverse psychological effect on older kids.

Older students don’t want to use Scratch because there’s nothing to gain from it and plenty to lose. If they’re good at it, congrats on being good at a little-kid language. If they’re bad at it, there’s no hope for them. They must be pitifully stupid.

Even code.org, a wonderful organization that’s done amazing work to promote CS education, makes this same mistake with their tagline, “Code.org: Anybody can learn.” They might as well say, “Code.org: You’d have to be an idiot not to get it.”

Students secretly crave challenges

When a student says, “I can’t do it. This is too hard,” it’s difficult not to reflexively reply, “No, it’s not. Look, it’s easy. You can do it.”

In our adult brains, this seems like the logical thing a student would want to hear. Easy is better than hard, right?

Wrong! Students crave hard. They seek it out wherever they can find it, athletic competitions, video games, chess, and debate. Hard things are great because:

- If you complete them, you’ve proven yourself. You did something that was outside of your ability, and that some of your peers couldn’t do. There’s a rewarding emotional high from completing a difficult task.

- However, if you fail at a hard task, it means nothing. After all, it wasn’t easy. Many people can’t do it. Maybe if you practice some more and come back later, you can give it another go.

So what do we do when a child comes to us, whining that a problem is too hard? We agree with them wholeheartedly. “Yes, this problem is really hard. You might not be able to complete it this time. Many students can’t do it. But if you keep working at it, I think you can get it.”

It’s not always the case, but students are usually excited to rise to the challenge.

The marketing solution for Scratch is counter-intuitive, but not impossible: tell kids Scratch is hard. This means removing all of the bright, primary colors, and childish cartoons. Replace them with harder, more standard adult colors and photos. Eschew rounded blocks for ones with hard edges.

Basically make Scratch look more like what kids imagine adult coding to look like.

However, if coding seems impossible, it could turn some students off from it entirely. Part of Scratch’s appeal is it’s accessibility. Potentially this means we should break Scratch into two products: leaving it the same for for true beginners that are younger than 12, and creating a new product that’s similar but seems more serious and real.

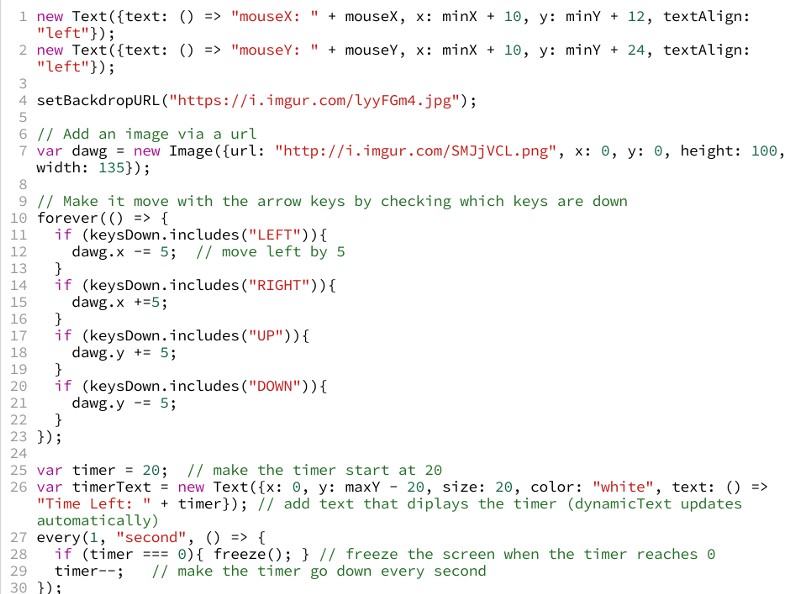

WoofJS

I now use WoofJS, a JavaScript framework we created at The Coding Space, to address this very program. It’s very similar to Scratch, but from within JavaScript, a “real” coding language. This way, students that think they are “done with Scratch” or “too old for Scratch” can get on board with learning similar concepts under new clothing. Woof serves as the bridge between Scratch and JavaScript that students are eager to walk across.

When I asked one of our 11-year-old students why she liked Woof better than Scratch, she said, “It’s more challenging.”

“Oh, is that because you have to learn JavaScript syntax?” I asked.

“No,” she thought for a moment. “I’m not really sure why it’s hard. But it just seems harder which is cool.”