By reading this post, you are going to really understand git merge, one of the most common operations you'll perform in your Git repositories.

Notes before we start

- I also created two videos covering the contents of this post. If you wish to watch alongside reading, you can find them here (Part 1, Part 2).

- I am working on a book about Git! Are you interested in reading the initial versions and providing feedback? Send me an email: gitting.things@gmail.com

OK, are you ready?

Table of Contents

- What is a Merge in Git?

- Time to Get Hands-on 🙌🏻

- Time For a More Advanced Case

- Quick recap on a three-way merge

- Moving on 👣

- More Advanced Git Merge Cases

- How Git's 3-way Merge Algorithm Works

- How to Resolve Merge Conflicts

- How to Use VS Code to Resolve Conflicts

- One More Powerful Tool 🪛

- Recap

What is a Merge in Git?

Merging is the process of combining the recent changes from several branches into a single new commit that will be on all those branches.

In a way, merging is the complement of branching in version control: a branch allows you to work simultaneously with others on a particular set of files, whereas a merge allows you to later combine separate work on branches that diverged from a common ancestor commit.

OK, let's take this bit by bit.

Remember that in Git, a branch is just a name pointing to a single commit. When we think about commits as being "on" a specific branch, they are actually reachable through the parent chain from the commit that the branch is pointing to.

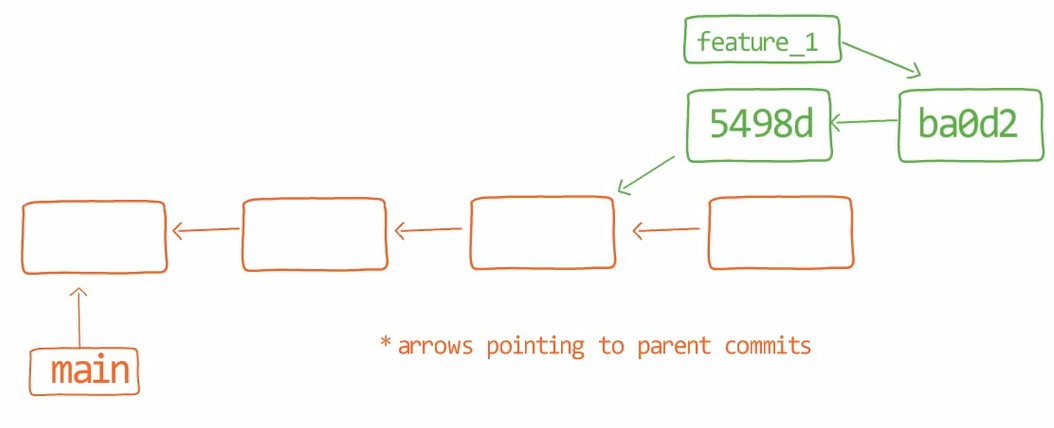

That is, if you consider this commit graph:

You see the branch feature_1, which points to a commit with the SHA-1 value of ba0d2. Of course, as in other posts, I only write the first 5 digits of the SHA-1 value.

Notice that commit 54a9d is also on this branch, as it is the parent commit of ba0d2. So if you start from the pointer of feature_1, you get to ba0d2, which then points to 54a9d.

When you merge with Git, you merge commits. Almost always, we merge two commits by referring to them with the branch names that point to them. Thus we say we "merge branches" – though under the hood, we actually merge commits.

Time to Get Hands-on 🙌🏻

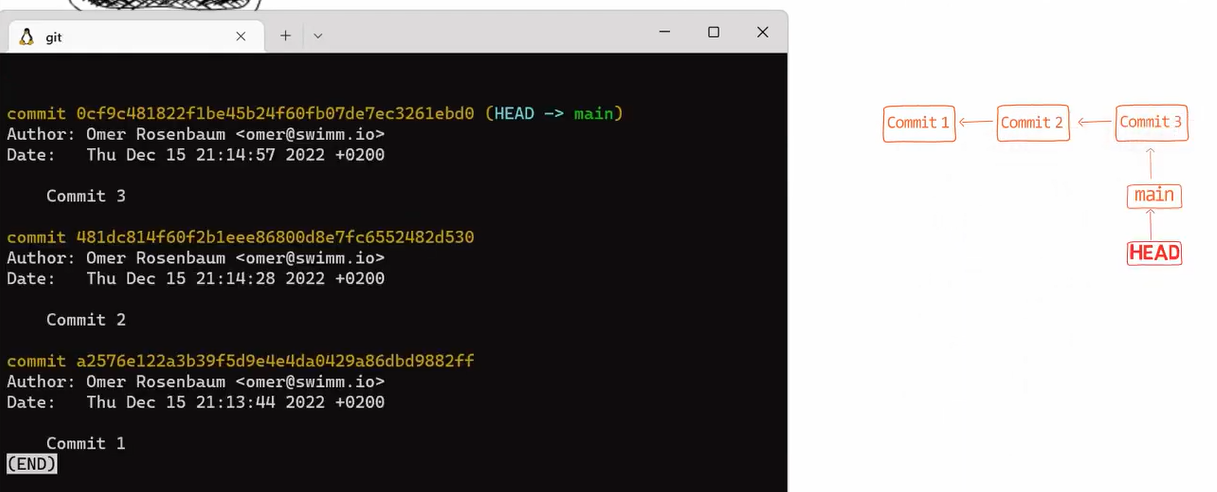

OK, so let's say I have this simple repository here, with a branch called main, and a few commits with the commit messages of "Commit 1", "Commit 2" and "Commit 3":

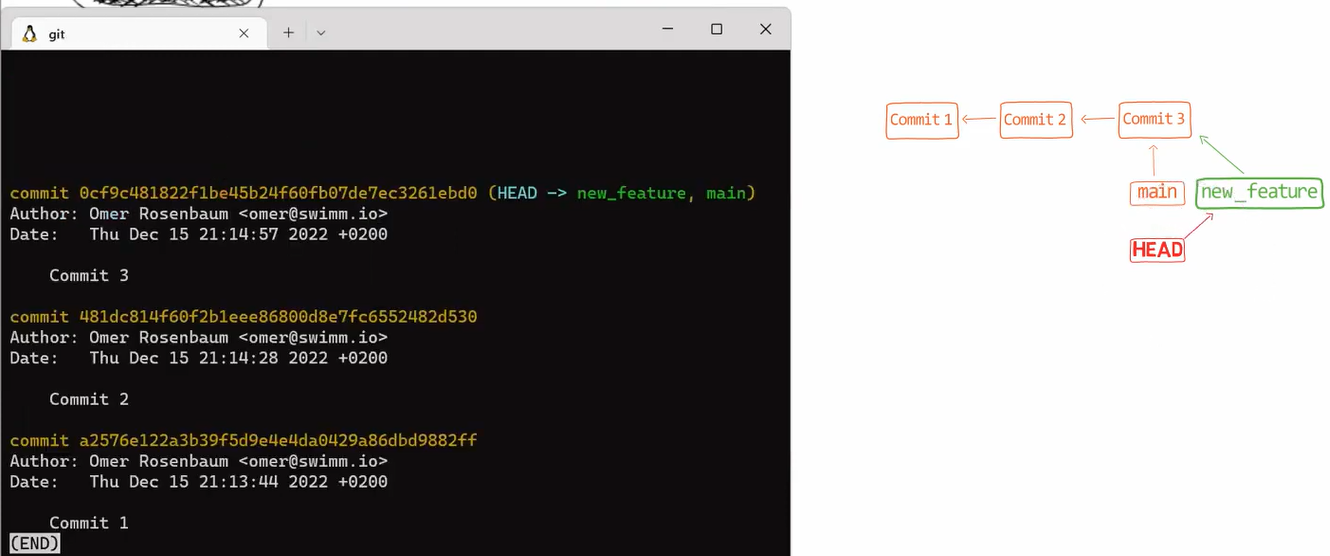

Next, create a feature branch by typing git branch new_feature:

git branch (Source: Brief)And switch HEAD to point to this new branch, by using git checkout new_feature. You can look at the outcome by using git log:

git log after using git checkout new_feature (Source: Brief)As a reminder, you could also write git checkout -b new_feature, which would both create a new branch and change HEAD to point to this new branch.

If you need a reminder about branches and how they're implemented under the hood, please check out a previous post on the subject. Yes, check out. Pun intended 😇

Now, on the new_feature branch, implement a new feature. In this example I will edit an existing file that looks like this before the edit:

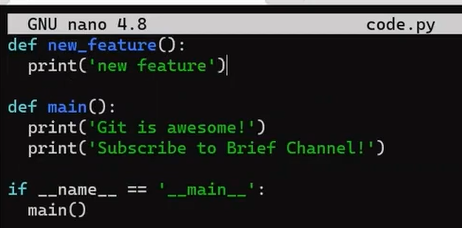

code.py before editing it (Source: Brief)And I will now edit it to include a new function:

new_feature (Source: Brief)And thankfully, this is not a programming tutorial, so this function is legit 😇

Next, stage and commit this change:

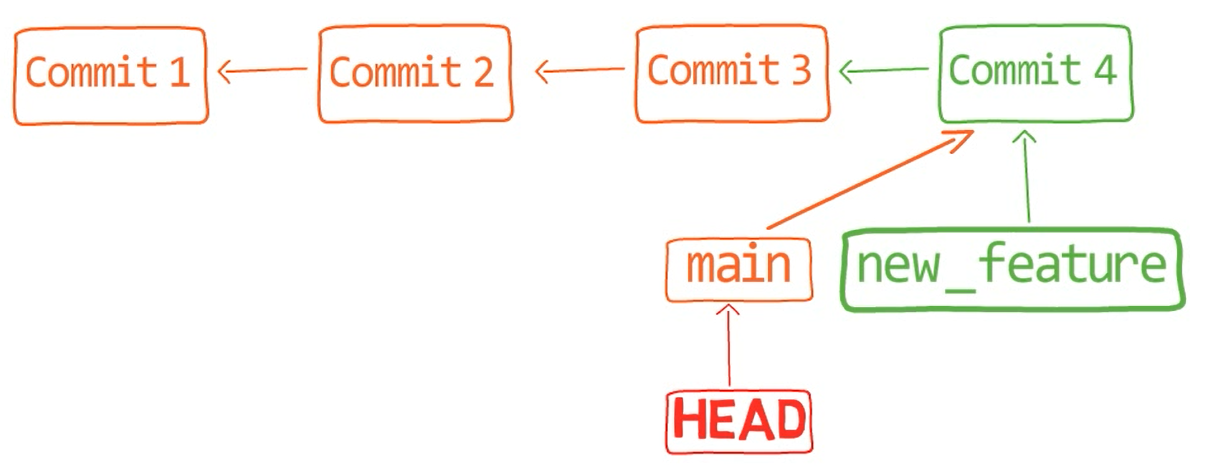

Looking at the history, you have the branch new_feature, now pointing to "Commit 4", which points to its parent, "Commit 3". The branch main is also pointing to "Commit 3".

Time to merge the new feature! That is, merge these two branches, main and new_feature. Or, in Git's lingo, merge new_feature into main. This means merging "Commit 4" and "Commit 3". This is pretty trivial, as after all, "Commit 3" is an ancestor of "Commit 4".

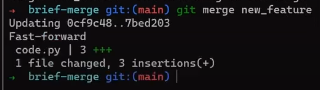

Check out the main branch (with git checkout main), and perform the merge by using git merge new_feature:

new_feature into main (Source: Brief)Since new_feature never really diverged from main, Git could just perform a fast-forward merge. So what happened here? Consider the history:

Even though you used git merge, there was no actual merging here. Actually, Git did something very simple – it reset the main branch to point to the same commit as the branch new_feature.

In case you don't want that to happen, but rather you want Git to really perform a merge, you could either change Git's configuration, or run the merge command with the --no-ff flag.

First, undo the last commit:

git reset --hard HEAD~1

If this way of using reset is not clear to you, feel free to check out a post where I covered git reset in depth. It is not crucial for this introduction of merge, though. For now, it's important to understand that it basically undoes the merge operation.

Just to clarify, now if you checked out new_feature again:

git checkout new_feature

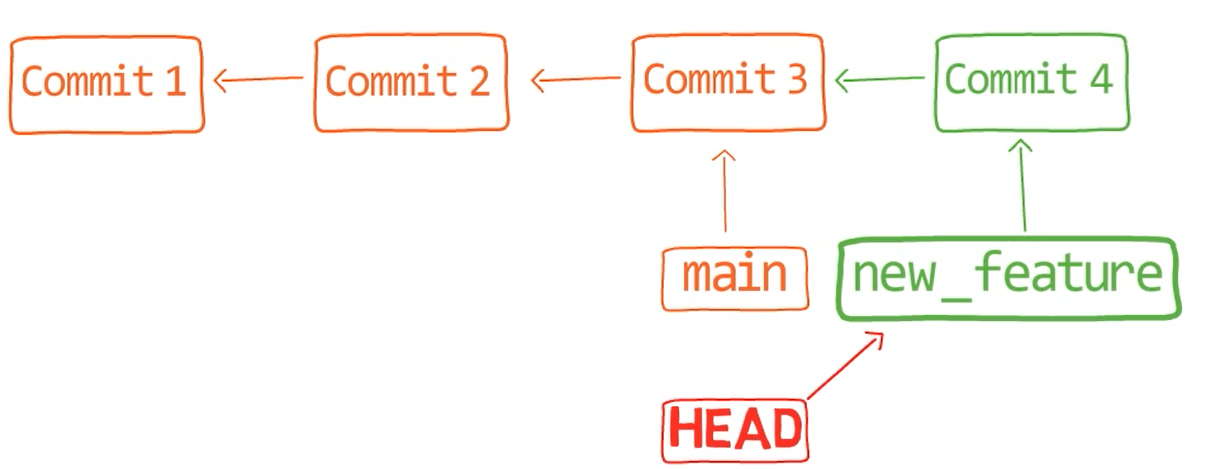

The history would look just like before the merge:

git reset --hard HEAD~1 (Source: Brief)Next, perform the merge with the --no-fast-forward flag (--no-ff for short):

git checkout main

git merge new_feature --no-ff

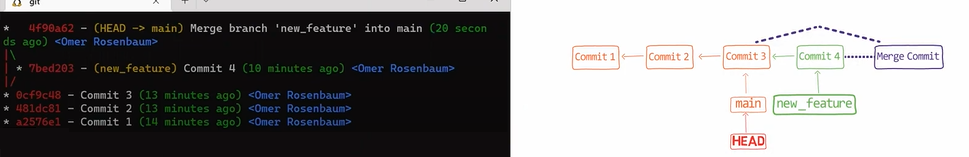

Now, if we look at the history using git lol:

--no-ff flag (Source: Brief)(git lol is an alias I added to Git to visibly see the history in a graphical manner. You can find it here).

Considering this history, you can see Git created a new commit, a merge commit.

If you consider this commit a bit closer:

git log -n1

You will see that this commit actually has two parents – "Commit 4", which was the commit that new_feature pointed to when you ran git merge, and "Commit 3", which was the commit that main pointed to. So a merge commit has two parents: the two commits it merged.

The merge commit shows us the concept of merge quite well. Git takes two commits, usually referenced by two different branches, and merges them together.

After the merge, as you started the process from main, you are still on main, and the history from new_feature has been merged into this branch. Since you started with main, then "Commit 3", which main pointed to, is the first parent of the merge commit, whereas "Commit 4", which you merged into main, is the second parent of the merge commit.

Notice that you started on main when it pointed to "Commit 3", and Git went quite a long way for you. It changed the working tree, the index, and also HEAD and created a new commit object. At least when you use git merge without the --no-commit flag and when it's not a fast-forward merge, Git does all of that.

This was a super simple case, where the branches you merged didn't diverge at all.

By the way, you can use git merge to merge more than two commits – actually, any number of commits. This is rarely done and I don't see a good reason to elaborate on it here.

Another way to think of git merge is by joining two or more development histories together. That is, when you merge, you incorporate changes from the named commits, since the time their histories diverged from the current branch, into the current branch. I used the term branch here, but I am stressing this again – we are actually merging commits.

Time For a More Advanced Case 💪🏻

Time to consider a more advanced case, which is probably the most common case where we use git merge explicitly – where you need to merge branches that did diverge from one another.

Assume we have two people working on this repo now, John and Paul.

John created a branch:

git checkout -b john_branch

john_branch (Source: Brief)And John has written a new song in a new file, lucy_in_the_sky_with_diamonds.md. Well, I believe John Lennon didn't really write in Markdown format, or use Git for that matter, but let's pretend he did for this explanation.

git add lucy_in_the_sky_with_diamonds.md

git commit -m "Commit 5"

While John was working on this song, Paul was also writing, on another branch. Paul had started from main:

git checkout main

And created his own branch:

git checkout -b paul_branch

And Paul wrote his song into a file:

nano penny_lane.md

And committed it:

git add penny_lane.md

git commit -m "Commit 6"

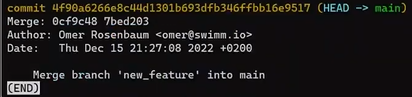

So now our history looks like this – where we have two different branches, branching out from main, with different histories.

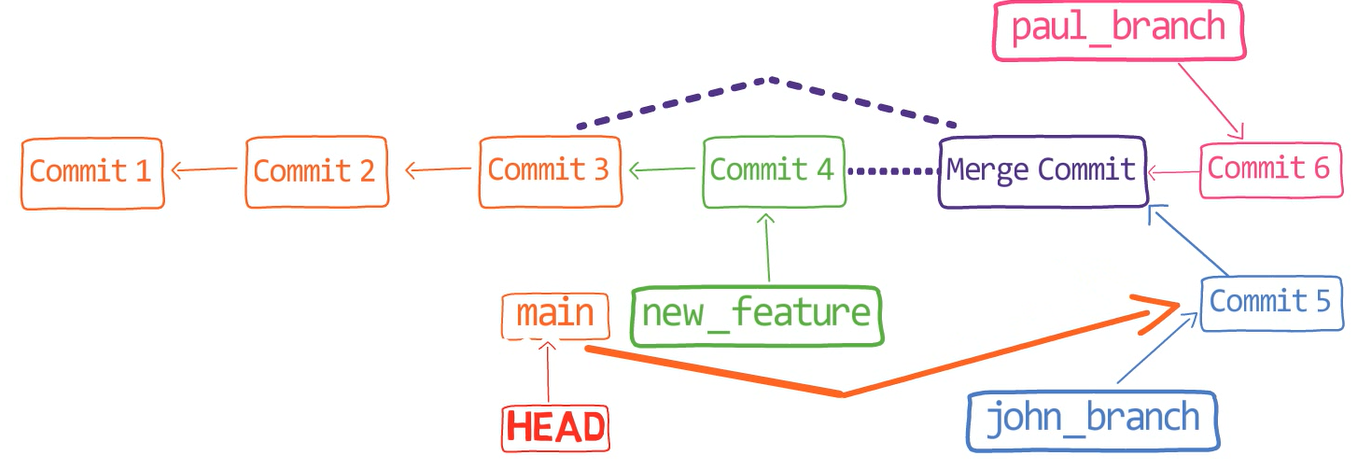

git lol shows the history after John and Paul committed (Source: Brief)John is happy with his branch (that is, his song), so he decides to merge it into the main branch:

git checkout main

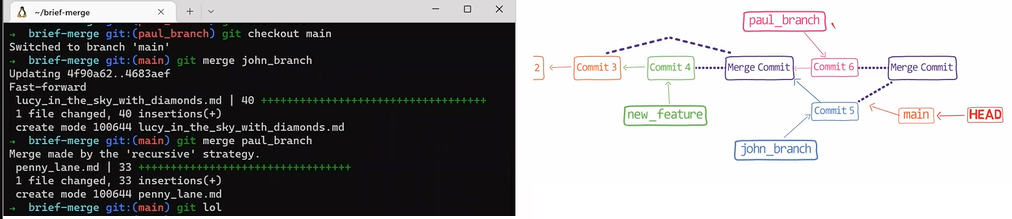

git merge john_branch

Actually, this is a fast-forward merge, as we have learned before. You can validate that by looking at the history (using git lol, for example):

john_branch into main results in a fast-forwrad merge (Source: Brief)At this point, Paul also wants to merge his branch into main, but now a fast-forward merge is no longer relevant – there are two different histories here: the history of main's and that of paul_branch's. It's not that paul_branch only adds commits on top of main branch or vice versa.

Now things get interesting. 😎😎

First, let Git do the hard work for you. After that, we will understand what's actually happening under the hood.

git merge paul_branch

Consider the history now:

paul_branch, you get a new merge commit (Source: Brief)What you have is a new commit, with two parents – "Commit 5" and "Commit 6".

In the working dir, you can see that both John's song as well as Paul's song are there:

ls

Nice, Git really did merge the changes for us. But how does that happen?

Undo this last commit:

git reset --hard HEAD~

How to perform a three-way merge in Git

It's time to understand what's really happening under the hood. 😎

What Git has done here is it called a 3-way merge. In outlining the process of a 3-way merge, I will use the term "branch" for simplicity, but you should remember you could also merge two (or more) commits that are not referenced by a branch.

The 3-way merge process includes these stages:

First, Git locates the common ancestor of the two branches. That is, the common commit from which the merging branches most recently diverged. Technically, this is actually the first commit that is reachable from both branches. This commit is then called the merge base.

Second, Git calculates two diffs – one diff from the merge base to the first branch, and another diff from the merge base to the second branch. Git generates patches based on those diffs.

Third, Git applies both patches to the merge base using a 3-way merge algorithm. The result is the state of the new, merge commit.

So, back to our example.

In the first step, Git looks from both branches – main and paul_branch – and traverses the history to find the first commit that is reachable from both. In this case, this would be...which commit?

Correct, "Commit 4".

If you are not sure, you can always ask Git directly:

git merge-base main paul_branch

By the way, this is the most common and simple case, where we have a single obvious choice for the merge base. In more complicated cases, there may be multiple possibilities for a merge base, but this is a topic for another post.

In the second step, Git calculates the diffs. So it first calculates the diff between "Commit 4" and "Commit 5":

git diff 4f90a62 4683aef

(The SHA-1 values will be different on your machine)

If you don't feel comfortable with the output of git diff, please read the previous post where I described it in detail.

You can store that diff to a file:

git diff 4f90a62 4683aef > john_branch_diff.patch

Next, Git calculates the diff between "Commit 4" and "Commit 6":

git diff 4f90a62 c5e4951

Write this one to a file as well:

git diff 4f90a62 c5e4951 > paul_branch_diff.patch

Now Git applies those patches on the merge base.

First, try that out directly – just apply the patches (I will walk you through it in a moment). This is not what Git really does under the hood, but it will help you gain a better understanding of why Git needs to do something different.

Checkout the merge base first, that is, "Commit 4":

git checkout 4f90a62

And apply John's patch first:

git apply -–index john_branch_diff.patch

Notice that for now there is no merge commit. git apply updates the working dir as well as the index, as we used the --index switch.

You can observe the status using git status:

So now John's new song is incorporated into the index. Apply the other patch:

git apply -–index paul_branch_diff.patch

As a result, the index contains changes from both branches.

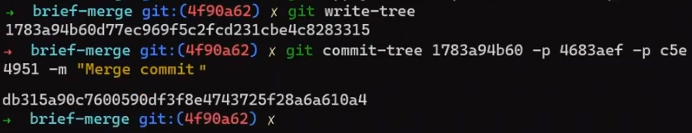

Now it's time to commit your merge. Since the porcelain command git commit always generates a commit with a single parent, you would need the underlying plumbing command – git commit-tree.

If you need a reminder about porcelain vs plumbing commands, check out the post where I explained these terms, and created an entire repo from scratch.

Remember that every Git commit object points to a single tree. So you need to record the contents of the index in a tree:

git write-tree

Now you get the SHA-1 value of the created tree, and you can create a commit object using git commit-tree:

git commit-tree <TREE_SHA> -p <COMMIT_4> -p <COMMIT_5> -m "Merge commit!"

Great, so you have created a commit object 💪🏻

Recall that git merge also changes HEAD to point to the new merge commit object. So you can simply do the same:

git reset –-hard db315a

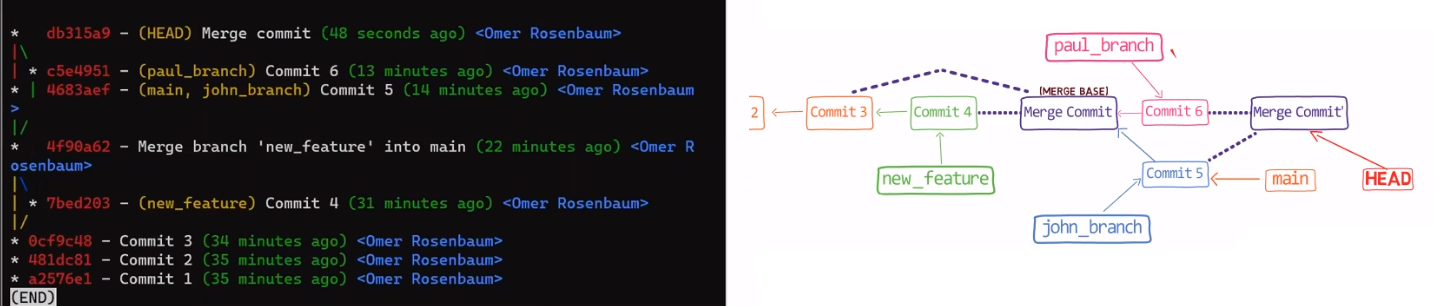

If you look at the history now:

HEAD (Source: Brief)You can see that you've reached the same result as the merge done by Git, with the exception of the timestamp and thus the SHA-1 value, of course.

So you got to merge both the contents of the two commits – that is, the state of the files, and also the history of those commits – by creating a merge commit that points to both histories.

In this simple case, you could actually just apply the patches using git apply, and everything worked quite well.

Quick recap on a three-way merge

So to quickly recap, on a three-way merge, Git:

- First, locates the merge base – the common ancestor of the two branches. That is, the first commit that is reachable from both branches.

- Second, Git calculates two diffs – one diff from the merge base to the first branch, and another diff from the merge base to the second branch.

- Third, Git applies both patches to the merge base, using a 3-way merge algorithm. I haven't explained the 3-way merge yet, but I will elaborate on that later. The result is the state of the new, merge commit.

You can also understand why it's called a "3-way merge": Git merges three different states – that of the first branch, that of the second branch, and their common ancestor. In our previous example, main, paul_branch, and Commit 4.

This is unlike, say, the fast-forward examples we saw before. The fast-forward examples are actually a case of a two-way merge, as Git only compares two states – for example, where main pointed to, and where john_branch pointed to.

Moving on 👣

Still, this was a simple case of a 3-way merge. John and Paul created different songs, so each of them touched a different file. It was pretty straightforward to execute the merge.

What about more interesting cases?

Let's assume that now John and Paul are co-authoring a new song.

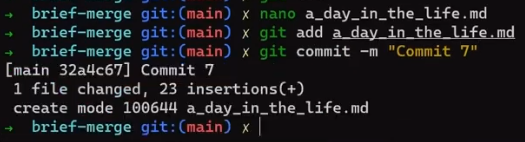

So, John checkedout main branch and started writing the song:

git checkout main

He staged and committed it ("Commit 7"):

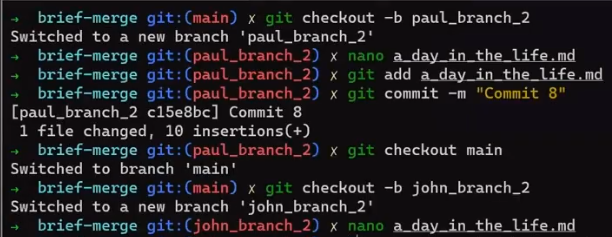

Now, Paul branches:

git checkout -b paul_branch_2

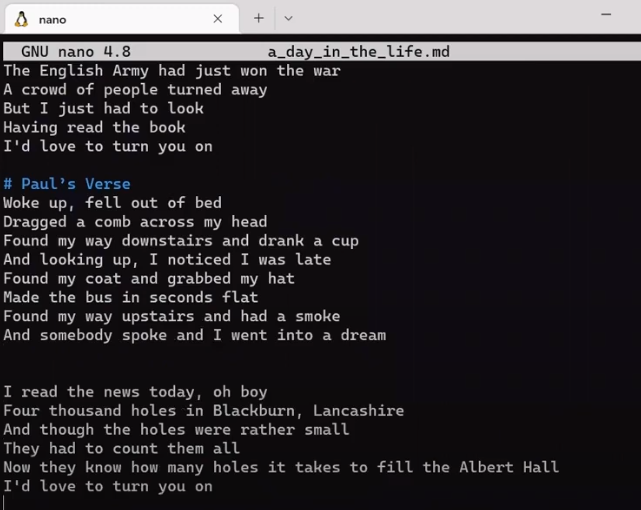

And edits the song, adding another verse:

Of course, in the original song, we don't have the title "Paul's Verse", but I'll add it here for simplicity.

Paul stages and commits the changes:

git add a_day_in_the_life.md

git commit -m "Commit 8"

John also branches out from main and adds a few last lines:

git checkout -b john_branch_2

And he stages and commits his changes too ("Commit 9"):

This is the resulting history:

So, both Paul and John modified the same file on different branches. Will Git be successful in merging them? 🤔

Say now we don't go through main, but John will try to merge Paul's new branch into his branch:

git merge paul_branch_2

Wait!! 🤚🏻 Don't run this command! Why would you let Git do all the hard work? You are trying to understand the process here.

So, first, Git needs to find the merge base. Can you see which commit that would be?

Correct, it would be the last commit on main branch, where the two diverged.

You can verify that by using:

git merge-base john_branch_2 paul_branch_2

Great, now Git should compute the diffs and generate the patches. You can observe the diffs directly:

git diff main paul_branch_2

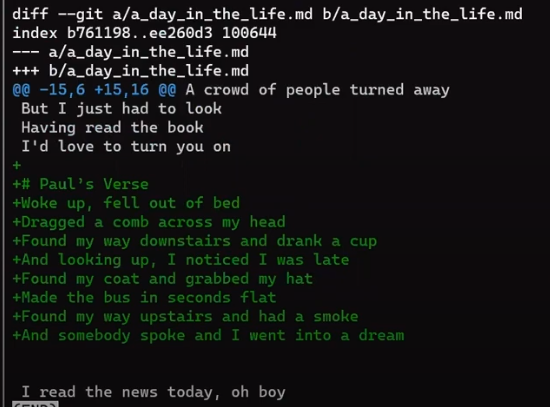

git diff main paul_branch_2 (Source: Brief)Will applying this patch succeed? Well, no problem, Git has all the context lines in place.

Ask Git to apply this patch:

git diff main paul_branch_2 > paul_branch_2.patch

git apply -–index paul_branch_2.patch

And this worked, no problem at all.

Now, compute the diff between John's new branch and the merge base. Notice that you haven't committed the applied changes, so john_branch_2 still points at the same commit as before, "Commit 9":

git diff main john_branch_2

git diff main john_branch_2 (Source: Brief)Will applying this diff work?

Well, indeed, yes. Notice that even though the line numbers have changed on the current version of the file, thanks to the context lines Git is able to locate where it needs to add these lines…

Save this patch and apply it then:

git diff main john_branch_2 > john_branch_2.patch

git apply –-index john_branch_2.patch

Observe the result file:

Cool, exactly what we wanted 👏🏻

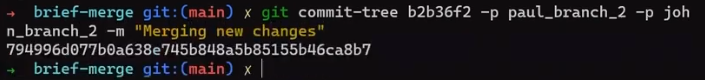

You can now create the tree and relevant commit:

git write-tree

Don't forget to specify both parents:

git commit-tree <TREE-ID> -p paul_branch_2 -p john_branch_2 -m "Merging new changes"

See how I used the branches names here? After all, they are just pointers to the commits we want.

Cool, look at the log from the new commit:

Exactly what we wanted.

You can also let Git perform the job for you. You can simply checkout john_branch_2, which you haven't moved – so it still points to the same commit as it did before the merge. So all you need to do is run:

git merge paul_branch_2

Observe the resulting history:

Just as before, you have a merge commit pointing to "Commit 8" and "Commit 9" as its parents. "Commit 9" is the first parent since you merged into it.

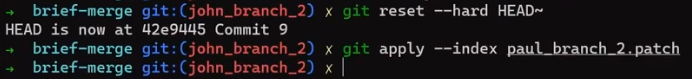

But this was still quite simple… John and Paul worked on the same file, but on very different parts. You could also directly apply Paul's changes to John's branch. If you go back to John's branch before the merge:

git reset --hard HEAD~

And now apply Paul's changes:

git apply -–index paul_branch_2.patch

You will get the same result.

But what happens when the two branches include changes on the same files, in the same locations? 🤔

More Advanced Git Merge Cases

What would happen if John and Paul were to coordinate a new song, and work on it together?

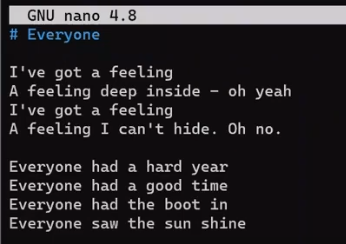

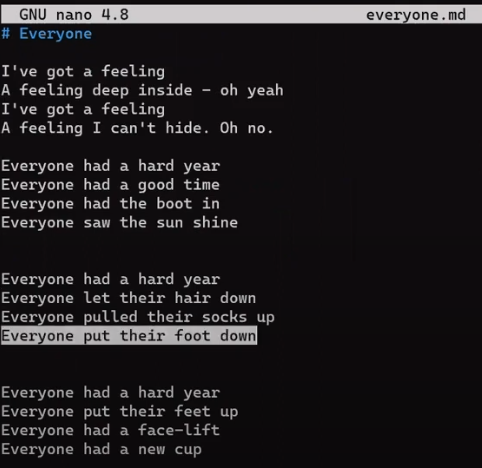

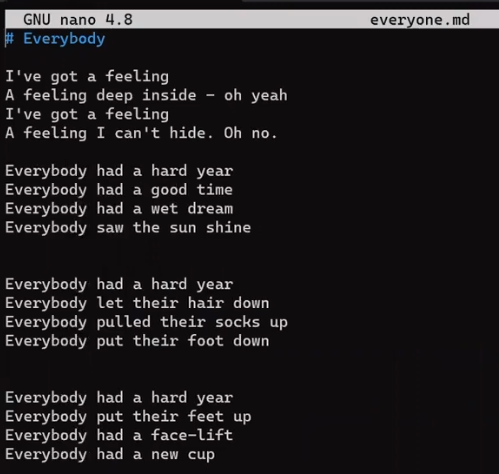

In this case, John creates the first version of this song in the main branch:

git checkout main

nano everyone.md

everyone.md prior to the first commit (Source: Brief)By the way, this text is indeed taken from the version that John Lennon recorded for a demo in 1968. But this isn't an article about the Beatles, so if you're curious about the process the Beatles underwent while writing this song, you can follow the links in the appendix below.

git add everyone.md

git commit -m "Commit 10"

Now John and Paul split. Paul creates a new verse in the beginning:

git checkout -b paul_branch_3

nano everyone.md

Also, while talking to John, they decided to change the word "feet" to "foot", so Paul adds this change as well.

And Paul adds and commits his changes to the repo:

git add everyone.md

git commit -m "Commit 11"

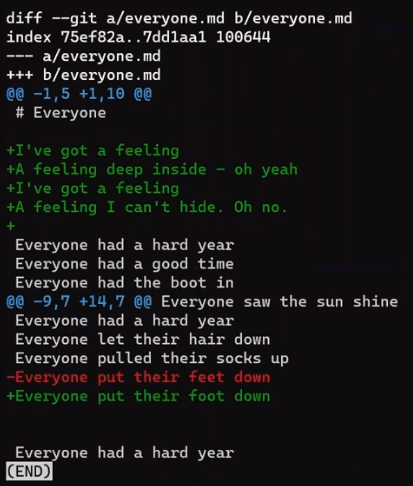

You can observe Paul's changes, by comparing this branch's state to the state of branch main:

git diff main

git diff main from Paul's branch (Source: Brief)Store this diff in a patch file:

git diff main > paul_3.patch

Now back to main...

git checkout main

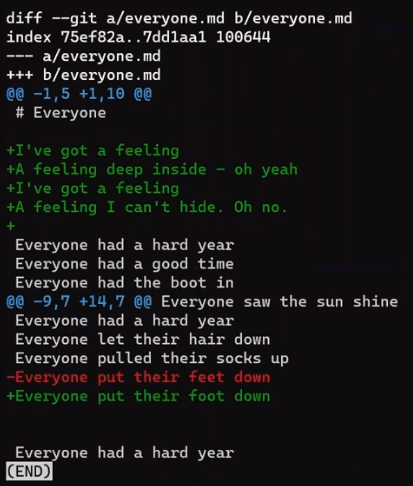

John decides to make another change, in his own new branch:

git checkout -b john_branch_3

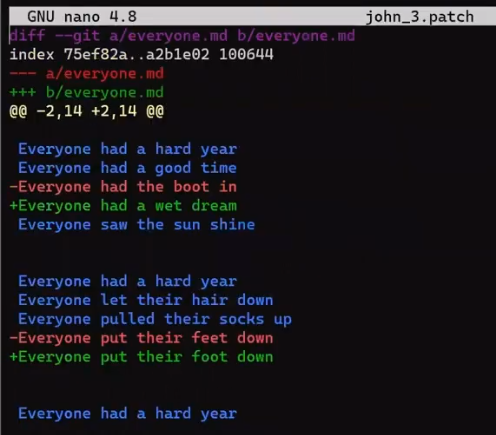

And he replaces the line "Everyone had the boot in" with the line "Everyone had a wet dream". In addition, John changed the word "feet" to "foot", following his talk with Paul.

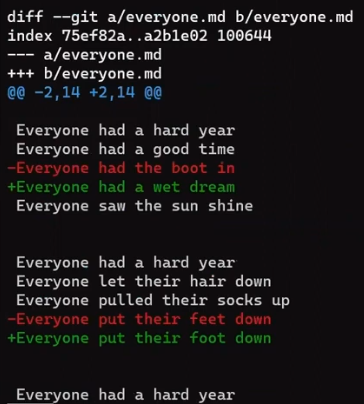

Observe the diff:

git diff main

git diff main from John's branch (Source: Brief)Store this output as well:

git diff main > john_3.patch

Now, stage and commit:

git add everyone.md

git commit -m "Commit 12"

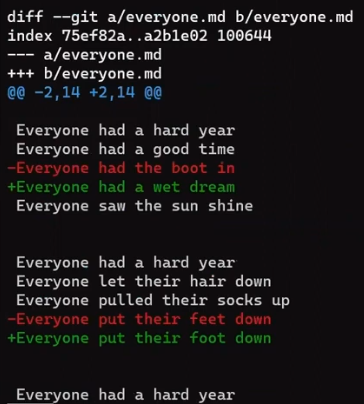

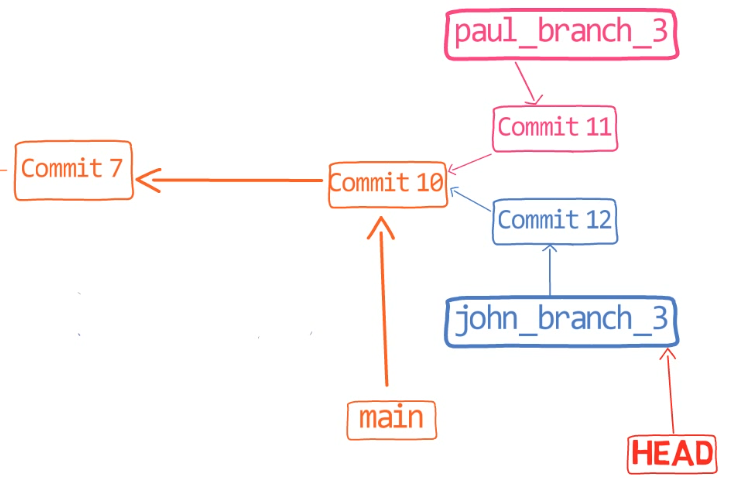

This is our current history:

Paul told John he added a new verse, so John would like to merge Paul's changes.

Can John simply apply Paul's patch?

Consider the patch again:

git diff main paul_branch_3

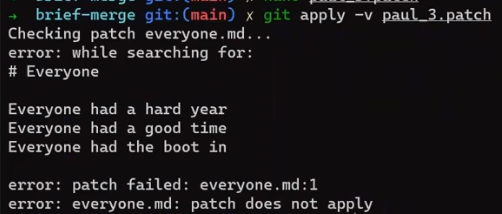

git diff main paul_branch_3 (Source: Brief)As you can see, this diff relies on the line "Everyone had the boot in", but this line no longer exists on John's branch. As a result, you could expect applying the patch to fail. Go on, give it a try:

git apply paul_3.patch

Indeed, you can see that it failed.

But should it really fail? 🤔

As explained earlier, git merge uses a 3-way merge algorithm, and this can come in handy here. What would be the first step of this algorithm?

Well, first, Git would find the merge base – that is, the common ancestor of Paul's branch and John's branch. Consider the history:

So the common ancestor of "Commit 11" and "Commit 12" is "Commit 10". We can verify this by running the command:

git merge-base john_branch_3 paul_branch_3

Now we can take the patches we generated from the diffs on both branches, and apply them to main. Would that work?

First, try to apply John's patch, and then Paul's patch.

Consider the diff:

git diff main john_branch_3

git diff main john_branch_3 (Source: Brief)We can store it in a file:

git diff main john_branch_3 > john_3.patch

And I want to apply this patch on main, so:

git checkout main

git apply john_3.patch

Let's consider the result:

nano everyone.md

everyone.md after applying John's patch (Source: Brief)The line changed as expected. Nice 😎

Now, can Git apply Paul's patch? To remind you, this is the patch:

Well, Git cannot apply this patch, because this patch assumes that the line "Everyone had the boot in" exists. Trying to apply is liable to fail:

git apply -v paul_3.branch

What you tried to do now, applying Paul's patch on main branch after applying John's patch, is the same as being on john_branch_3, and attempting to apply the patch, that is:

git apply paul_3.patch

What would happen if we tried the other way around?

First, clean up the state:

git reset --hard

And start from Paul's branch:

git checkout paul_branch_3

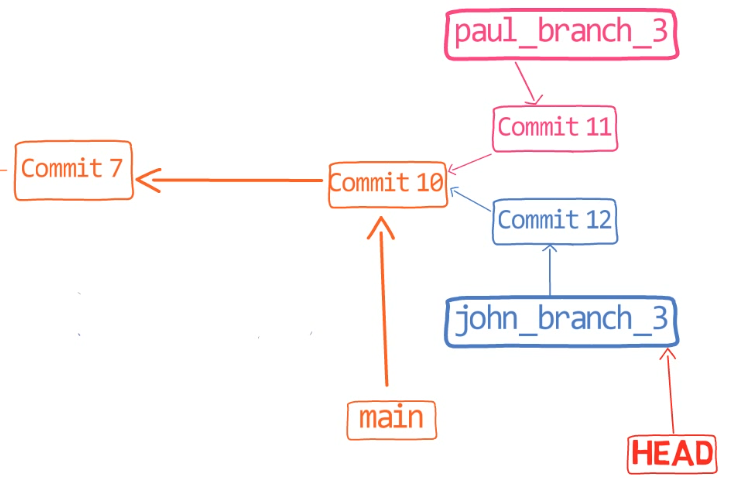

Can we apply John's patch? As a reminder, this is the status of everyone.md on this branch:

everyone.md on paul_branch_3 (Source: Brief)And this is John's patch:

Would applying John's patch work? 🤔

Try to answer yourself before reading on.

You can try:

git apply john_3.patch

Well, no! Again, if you are not sure what happened, you can always ask git apply to be a bit more verbose:

git apply john_3.patch -v

-v flag (Source: Brief)Git is looking for "Everyone put the feet down", but Paul has already changed this line so it now consists of the word "foot" instead of "feet". As a result, applying this patch fails.

Notice that changing the number of context lines here (that is, using git apply with the -C flag, as discussed in a previous post) is irrelevant – Git is unable to locate the actual line that the patch is trying to erase.

But actually, Git can make this work, if you just add a flag to apply, telling it to perform a 3-way merge under the hood:

git apply -3 john_3.patch

-3 flag succeeds (Source: Brief)And let's consider the result:

everyone.md after ther merge (Source: Brief)Exactly what we wanted! You have Paul's verse (marked in the image above), and both of John's changes!

So, how was Git able to accomplish that?

Well, as I mentioned, Git really did a 3-way merge, and with this example, it will be a good time to dive into what this actually means.

How Git's 3-way Merge Algorithm Works

Get back to the state before applying this patch:

git reset --hard

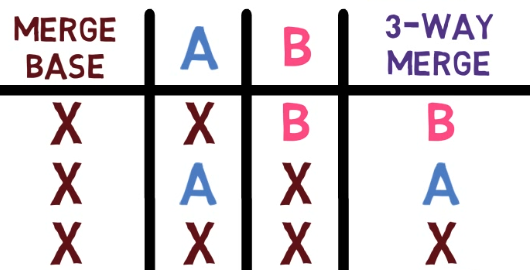

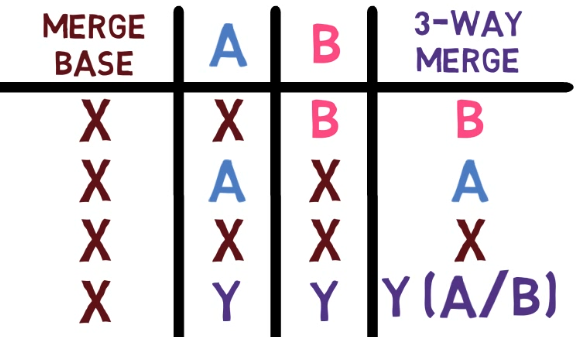

You have now three versions: the merge base, which is "Commit 10", Paul's branch, and John's branch. In general terms, we can say these are the merge base, commit A and commit B. Notice that the merge base is by definition an ancestor of both commit A and commit B.

To perform the merge, Git looks at the diff between the three different versions of the file in question on these three revisions. In your case, it's the file everyone.md, and the revisions are "Commit 10", Paul's branch – that is, "Commit 11", and John's branch, that is, "Commit 12".

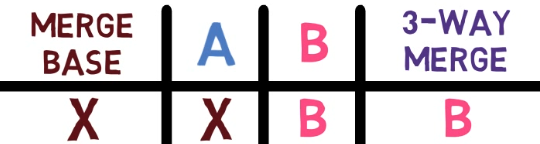

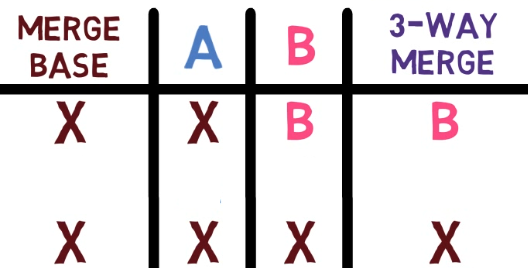

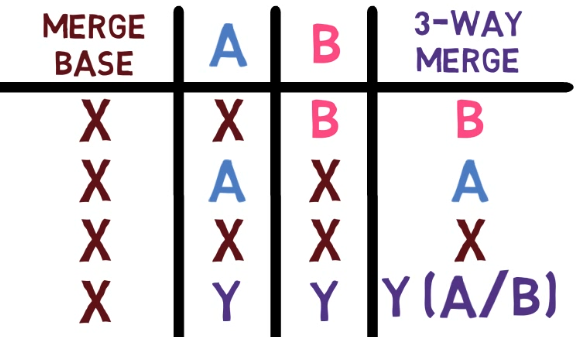

Git makes the merging decision based on the status of each line in each of these versions.

In case not all three versions match, that is a conflict. Git can resolve many of these conflicts automatically, as we will now see.

Let's consider specific lines.

The first lines here exist only on Paul's branch:

This means that the state of John's branch is equal to the state of the merge base. So the 3-way merge goes with Paul's version.

In general, if the state of the merge base is the same as A, the algorithm goes with B. The reason is that since the merge base is the ancestor of both A and B, Git assumes that this line hasn't changed in A, and it has changed in B, which is the most recent version for that line, and should thus be taken into account.

A, and this state is different from B, the algorithm goes with B (Source: Brief)Next, you can see lines where all three versions agree – they exist on the merge base, A and B, with equal data.

So the algorithm has a trivial choice – just take that version.

In a previous example, we saw that if the merge base and A agree, and B's version is different, the algorithm picks B. This works in the other direction too – for example, here you have a line that exists on John's branch, different than that on the merge base and Paul's branch.

Hence, John's version is chosen.

B, and this state is different from A, the algorithm goes with A (Source: Brief)Now consider another case, where both A and B agree on a line, but the value they agree upon is different from the merge base – both John and Paul agreed to change the line "Everyone put their feet down" to "Everyone put their foot down":

In this case, the algorithm picks the version on both A and B.

A and B agree on a version which is different from the merge base's version, the algorithm picks the version on both A and B (Source: Brief)Notice this is not a democratic vote. In the previous case, the algorithm picked the minority version, as it resembled the newest version of this line. In this case, it happens to pick the majority – but only because A and B are the revisions that agree on the new version.

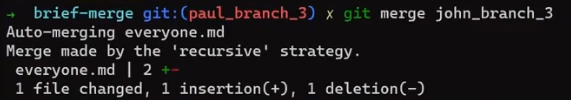

The same would happen if we used git merge:

git merge john_branch_3

Without specifying any flags, git merge will default to using a 3-way merge.

git merge uses a 3-way merge algorithm (Source: Brief)The status of everyone.md after running the command above would be the same as the result you achieved by applying the patches with git apply -3.

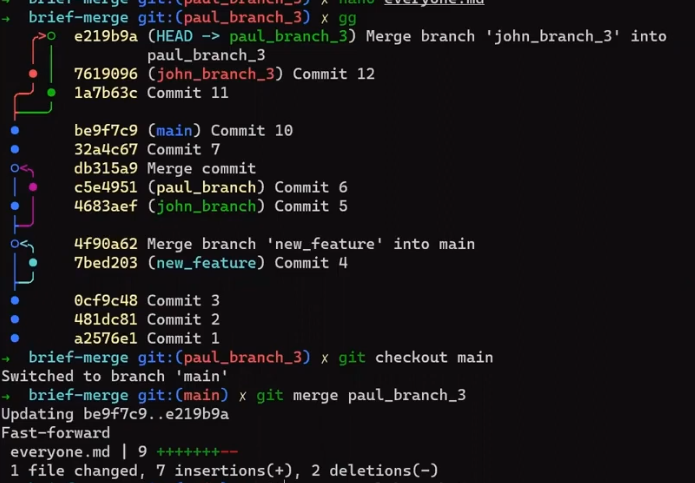

If you consider the history:

You will see that the merge commit indeed has two parents: the first is "Commit 11", that is, where paul_branch_3 pointed to before the merge. The second is "Commit 12", where john_branch_3 pointed to, and still points to now.

What will happen if you now merge from main? That is, switch to the main branch, which is pointing to "Commit 10":

git checkout main

And then merge Paul's branch?

git merge paul_branch_3

Indeed, a fast forward, as before running this command, main was an ancestor of paul_branch_3.

So, this is a 3-way merge. In general, if all versions agree on a line, then this line is used. If A and the merge base match, and B has another version, B is taken. In the opposite case, where the merge base and B match, the A version is selected. If A and B match, this version is taken, whether the merge base agrees or not.

This description leaves one open question though: What happens in cases where all three versions disagree?

Well, that's a conflict that Git does not resolve automatically. In these cases, Git calls for a human's help.

How to Resolve Merge Conflicts

By following so far, you should understand the basics of git merge, and how Git can automatically resolve some conflicts. You also understand what cases are automatically resolved.

Next, let's consider a more advanced case.

Say Paul and John keep working on this song.

Paul creates a new branch:

git checkout -b paul_branch_4

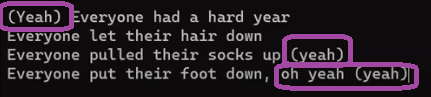

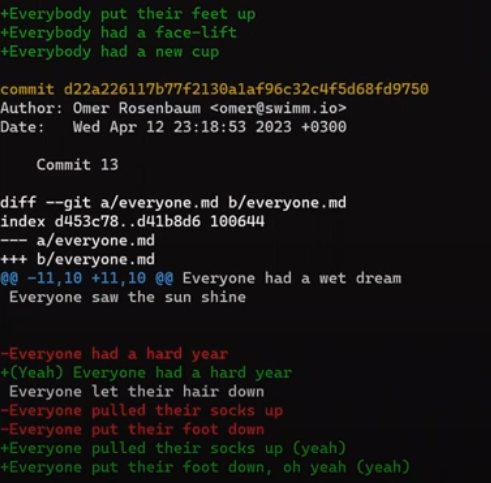

And he decides to add some "Yeah"s to the song, so he changes this verse as follows:

So Paul stages and commits these changes:

git commit -m "Commit 13"

Paul also creates another song, let_it_be.md and adds it to the repo:

git add let_it_be.md

git commit -m "Commit 14"

This is the history:

Back to main:

git checkout main

John also branches out:

git checkout -b john_branch_4

And John also works on the song "Everyone had a hard year", later to be called "I've got a feeling" (again, this is not an article about the Beatles, so I won't elaborate on it here. See the appendix if you are curious).

John decides to change all occurrences of "Everyone" to "Everybody":

He stages and commits this song to the repo:

git add everyone.md

git commit -m "Commit 15"

Nice. Now John also creates another song, across_the_universe.md. He adds it to the repo as well:

git add across_the_universe.md

git commit -m "Commit 16"

Observe the history again:

You can see that the history diverges from main, to two different branches – paul_branch_4, and john_branch_4.

At this point, John would like to merge the changes introduced by Paul.

What is going to happen here?

Remember the changes introduced by Paul:

git diff main paul_branch_4

git diff main paul_branch_4 (Source: Brief)What do you think? Will merge work? 🤔

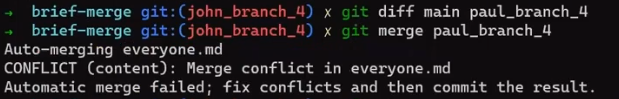

Try it out:

git merge paul_branch_4

We have a conflict! 🥁

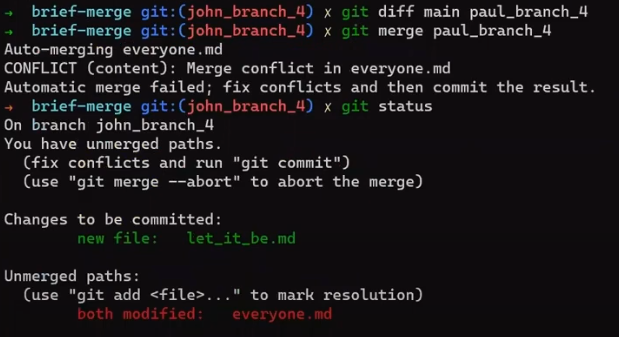

It seems that Git cannot merge these branches on its own. You can get an overview of the merge state, using git status:

git status right after the merge operation (Source: Brief)The changes that Git had no problem resolving are staged for commit. And there is a separate section for "unmerged paths" – these are files with conflicts that Git could not resolve on its own.

It's time to understand why and when these conflicts happen, how to resolve them, and also how Git handles them under the hood.

Alright then! I hope you are at least as excited as I am. 😇

Let's recall what we know about 3-way merges:

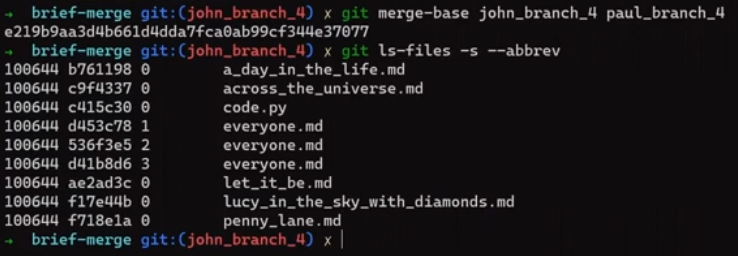

First, Git will look for the merge base – the common ancestor of john_branch_4 and paul_branch_4. Which commit would that be?

Correct, it would be the tip of main branch, the commit in which we merged john_branch_3 into paul_branch_3.

Again, if you are not sure, you can verify that by running:

git merge-base john_branch_4 paul_branch_4

And at the current state, git status knows which files are staged and which aren't.

Consider the process for each file, which is the same as the 3-way merge algorithm we considered per line, but on a file's level:

across_the_universe.md exists on John's branch, but doesn't exist on the merge base or on Paul's branch. So Git chooses to include this file. Since you are already on John's branch and this file is included in the tip of this branch, it is not mentioned by git status.

let_it_be.md exists on Paul's branch, but doesn't exist on the merge-base or John's branch. So git merge "chooses" to include it.

What about everyone.md? Well, here we have three different states of this file: its state on the merge base, its state on John's branch, and its state on Paul's branch. While performing a merge, Git stores all of these versions on the index.

Let's observe that by looking directly at the index with the command git ls-files:

git ls-files -s –-abbrev

git ls-files -s –-abbrev after the merge operation (Source: Brief)You can see that everyone.md has three different entries. Git assigns each version a number that represents the "stage" of the file, and this is a distinct property of an index entry, alongside the file's name and the mode bits (I covered the index in a previous post).

When there is no merge conflict regarding a file, its "stage" is 0. This is indeed the state for across_the_universe.md, and for let_it_be.md.

On a conflict's state, we have:

- Stage

1– which is the merge base. - Stage

2– which is "your" version. That is, the version of the file on the branch you are merging into. In our example, this would bejohn_branch_4. - Stage

3– which is "their" version, also called theMERGE_HEAD. That is, the version on the branch you are merging (into the current branch). In our example, that ispaul_branch_4.

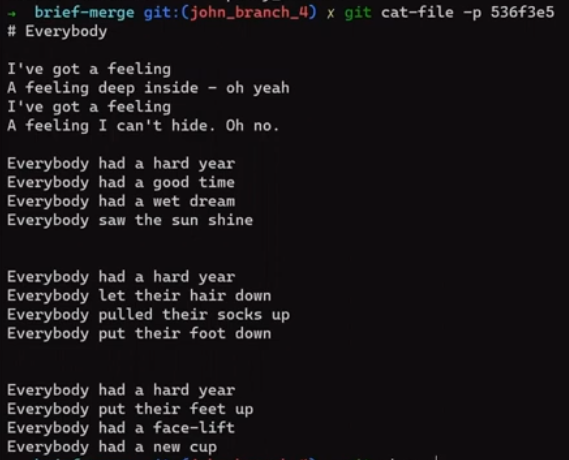

To observe the file's contents in a specific stage, you can use a command I introduced in a previous post, git cat-file, and provide the blob's SHA:

git cat-file -p <BLOB_SHA_FOR_STAGE_2>

git cat-file to present the content of the file on John's branch, right from its state in the index (Source: Brief)And indeed, this is the content we expected – from John's branch, where the lines start with "Everybody" rather than "Everyone".

A nice trick that allows you to see the content quickly without providing the blob's SHA-1 value, is by using git show, like so:

git show :<STAGE>:everyone.md

For example, to get the content of the same version as with git cat-file -p <BLOB_SHA_FOR_STAGE_2>, you can write git show :2:everyone.md.

Git records the three states of the three commits into the index in this way at the start of the merge. It then follows the three-way merge algorithm to quickly resolve the simple cases:

In case all three stages match, then the selection is trivial.

If one side made a change while the other did nothing – that is, stage 1 matches stage 2, then we choose stage 3 – or vice versa. That's exactly what happened with let_it_be.md and across_the_universe.md.

In case of a deletion on the incoming branch, for example, and given there were no changes on the current branch, then we would see that stage 1 matches stage 2, but there is no stage 3. In this case, git merge removes the file for the merged version.

What's really cool here is that for matching, Git doesn't need the actual files. Rather, it can rely on the SHA-1 values of the corresponding blobs. This way, Git can easily detect the state a file is in.

Cool, so for everyone.md you have this special case – where stage 1, stage 2 and stage 3 are all different from one another. That is, they have different blob SHAs. It's time to go deeper and understand the merge conflict. 😊

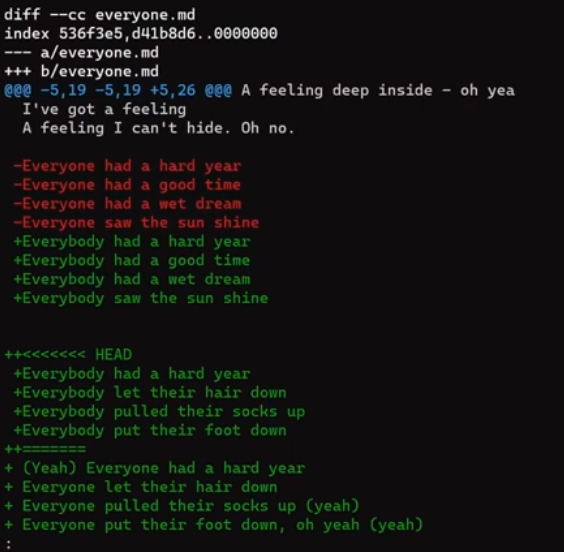

One way to do that would be to simply use git diff. In a previous post, we examined git diff in detail, and saw that it shows the differences between various combinations of the working tree, index or commits.

But git diff also has a special mode for helping with merge conflicts:

git diff

git diff during a conflict (Source: Brief)This output may be confusing at first, but once you get used to it, it's pretty clear. Let's start by understanding it, and then see how you can resolve conflicts with other, more visual tools.

The conflicted section is separated by the "equal" marks (====), and marked with the corresponding branches. In this context, "ours" is the current branch. In this example, that would be john_branch_4, the branch that HEAD was pointing to when we initiated the git merge command. "Theirs" is the MERGE_HEAD, the branch that we are merging in – in this case, paul_branch_4.

So git diff without any special flags shows changes between the working tree and the index, which in this case are the conflicts yet to be resolved. The output doesn't include staged changes, which is very convenient for resolving the conflict.

Time to resolve this manually. Fun!

So, why is this a conflict?

For Git, Paul and John made different changes to the same line, for a few lines. John changed it to one thing, and Paul changed it to another thing. Git cannot decide which one is correct.

This is not the case for the last lines, like the line that used to be "Everyone had a hard year" on the merge base. Paul hasn't changed this line, or the lines surrounding it, so its version on paul_branch_4, or "theirs" in our case, agrees with the merge_base. Yet John's version, "ours", is different. Thus git merge can easily decide to take this version.

But what about the conflicted lines?

In this case, I know what I want, and that is actually a combination of these lines. I want the lines to start with Everybody, following John's change, but also to include Paul's "yeah"s. So go ahead and create the desired version by editing everyone.md:

nano everyone.md

To compare the result file to what you had in the branch prior to the merge, you can run:

git diff --ours

Similarly, if you wish to see how the result of the merge differs from the branch you merged into our branch, you can run:

git diff -–theirs

You can even see how the result is different from both sides using:

git diff -–base

Now you can stage the fixed version:

git add everyone.md

After staging, if you look at git status, you will see no conflicts:

everyone.md, there are no conflicts (Source: Brief)You can now simply use git commit, and Git will present you with a commit message containing details about the merge. You can modify it if you like, or leave it as is. Regardless of the commit message, Git will create a "merge commit" – that is, a commit with more than one parent.

To validate that, consider the history:

john_branch_4 now points to the new merge commit. The incoming branch, "theirs", in this case, paul_branch_4, stays where it was.

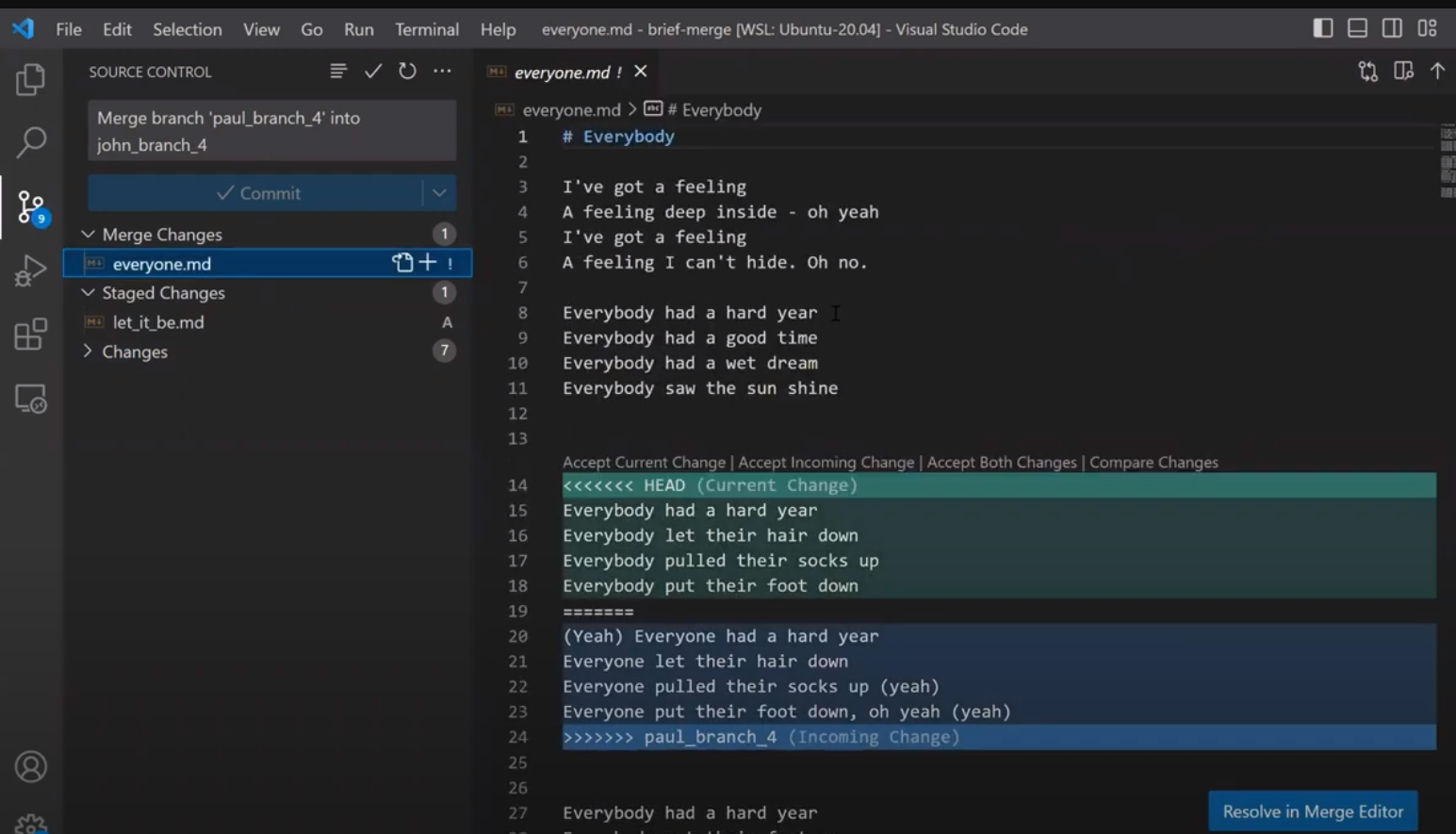

How to Use VS Code to Resolve Conflicts

I will show you now how to resolve the same conflict using a graphical tool. For this example, I will use VS Code, which is free and very common. There are many other tools, yet the process is similar, so I will just show VS Code as an example.

First, get back to the state before the merge:

git reset --hard HEAD~

And try to merge again:

git merge paul_branch_4

You should be back at the same status:

Let's see how this appears on VS Code:

VS Code marks the different versions with "Current Change" – which is the "ours" version, the current HEAD, and "Incoming Change" for the branch we are merging into the active branch. You can accept one of the changes (or both) by clicking on one of the options.

If you clicked on Resolve in Merge editor, you would get a more visual view of the state. VS Code shows the status of each line:

If you look closely, you will see that VS Code shows changes within words – for example, showing that "Everyone" was changed to "Everybody", marking the changed parts.

You can accept either version, or you can accept a combination. In this case, if you click on "Accept Combination", you get this result:

VS Code did a really good job! The same three way merge algorithm was implemented here and used on the word level rather than the line level. So VS Code was able to actually resolve this conflict in a rather impressive way. Of course, you can modify VS Code's suggestion, but it provided a very good start.

One More Powerful Tool 🪛

Well, this was the first time in this entire series of Git articles that I use a tool with a graphical user interface. Indeed, graphical interfaces can be very convenient to understand what's going on when you are resolving merge conflicts.

However, like in many other cases, when we need the big guns or really understand what's going on, the command line becomes handy. So let's get back to the command line and learn a tool that can come in handy in more complicated cases.

Again, go back to the state before the merge:

git reset --hard HEAD~

And merge:

git merge paul_branch_4

And say, you are not exactly sure what happened. Why is there a conflict? One very useful command would be:

git log -p -–merge

As a reminder, git log shows the history of commits that are reachable from HEAD. Adding -p tells git log to show the commits along the diffs they introduced. The --merge switch makes the command show all commits containing changes relevant to any unmerged files, on either branch, together with their diffs.

This can help you identify the changes in history that led to the conflicts. So in this example, you'd see:

git log -p -–merge (Source: Brief)The first commit we see is "Commit 15", as in this commit John modified everyone.md, a file that still has conflicts. Next, Git shows "Commit 13", where Paul changed everyone.md:

git log -p -–merge - continued (Source: Brief)Notice that git log --merge did not mention previous commits that had changed everyone.md before "Commit 13", as they had not affected the current conflict.

This way, git log tells you all you need to know to understand the process that got you into the current conflicting state. Cool! 😎

Using the command line, you can also ask Git to take only one side of the changes – either "ours" or "theirs", even for a specific file.

You can also instruct Git to take some parts of the diffs of one file and another from another file. I will provide links that describe how to do that in the additional resources section below.

For the most part, you can accomplish that pretty easily either manually or from the UI of your favorite IDE.

For now, it's time for a recap.

Recap

In this guide, you got an extensive overview of merging with Git. You learned that merging is the process of combining the recent changes from several branches into a single new commit. The new commit has two parents – those commits which had been the tips of the branches that were merged.

We considered a simple, fast-forward merge, which is possible when one branch diverged from the base branch, and then just added commits on top of the base branch.

We then considered three-way merges, and explained the three-stage process:

- First, Git locates the merge base. As a reminder, this is the first commit that is reachable from both branches.

- Second, Git calculates two diffs – one diff from the merge base to the first branch, and another diff from the merge base to the second branch. Git generates patches based on those diffs.

- Third and last, Git applies both patches to the merge base using a 3-way merge algorithm. The result is the state of the new, merge commit.

We dove deeper into the process of a 3-way merge, whether at a file level or a hunk level. We considered when Git is able to rely on a 3-way merge to automatically resolve conflicts, and when it just can't.

You saw the output of git diff when we are in a conflicting state, and how to resolve conflicts either manually or with VS Code.

There is much more to be said about merges – different merge strategies, recursive merges, and so on. Yet, after this guide, you should have a robust understanding of what merge is, and what happens under the hood in the vast majority of cases.

About the Author

Omer Rosenbaum is Swimm’s Chief Technology Officer. He's the author of the Brief YouTube Channel. He's also a cyber training expert and founder of Checkpoint Security Academy. He's the author of Computer Networks (in Hebrew). You can find him on Twitter.

Additional References

- Git Internals YouTube playlist — by Brief.

- Omer's previous post about Git internals.

- Omer's piece about Git UNDO - rewriting history with Git.

- https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Advanced-Merging.

- https://blog.plasticscm.com/2010/11/live-to-merge-merge-to-live.html.

- https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/git-pocket-guide/9781449327507/ch07.html.

- https://jwiegley.github.io/git-from-the-bottom-up/1-Repository/4-how-trees-are-made.html.