The React Handbook follows the 80/20 rule: learn in 20% of the time the 80% of a topic.

I find this approach gives a well-rounded overview. This book does not try to cover everything under the sun related to React, but it should give you the basic building blocks to get out there and become a great React developer. If you think some specific topic should be included, tell me. You can reach me on Twitter @flaviocopes.

I hope the contents of this book will help you achieve what you want: learn the basics of React.

You can get this ebook in PDF, ePub and Mobi format at reacthandbook.com

Book Index

Table of Contents

An introduction to React

How to use create-react-app

SECTION 1: MODERN JAVASCRIPT CORE CONCEPTS YOU NEED TO KNOW TO USE REACT

- Variables

- Arrow functions

- Rest and spread

- Object and array destructuring

- Template literals

- Classes

- Callbacks

- Promises

- Async/Await

- ES Modules

SECTION 2: REACT CONCEPTS

- Single Page Applications

- Declarative

- Immutability

- Purity

- Composition

- The Virtual DOM

- Unidirectional Data Flow

SECTION 3: IN-DEPTH REACT

- JSX

- Components

- State

- Props

- Presentational vs container components

- State vs props

- PropTypes

- React Fragment

- Events

- Lifecycle Events

- Forms in React

- Reference a DOM element

- Server side rendering

- The Context API

- Higher order components

- Render Props

- Hooks

- Code splitting

SECTION 4: PRACTICAL EXAMPLES

SECTION 5: STYLING

SECTION 6: TOOLING

SECTION 7: TESTING

SECTION 8: THE REACT ECOSYSTEM

An introduction to the React view library

What is React?

React is a JavaScript library that aims to simplify development of visual interfaces.

Developed at Facebook and released to the world in 2013, it drives some of the most widely used apps, powering Facebook and Instagram among countless other applications.

Its primary goal is to make it easy to reason about an interface and its state at any point in time, by dividing the UI into a collection of components.

Why is React so popular?

React has taken the frontend web development world by storm. Why?

Less complex than the other alternatives

At the time when React was announced, Ember.js and Angular 1.x were the predominant choices as a framework. Both these imposed so many conventions on the code that porting an existing app was not convenient at all.

React made a choice to be very easy to integrate into an existing project, because that’s how they had to do it at Facebook in order to introduce it to the existing codebase. Also, those 2 frameworks brought too much to the table, while React only chose to implement the View layer instead of the full MVC stack.

Perfect timing

At the time, Angular 2.x was announced by Google, along with the backwards incompatibility and major changes it was going to bring. Moving from Angular 1 to 2 was like moving to a different framework, so this, along with execution speed improvements that React promised, made it something developers were eager to try.

Backed by Facebook

Being backed by Facebook is, of course, going to benefit a project if it turns out to be successful.

Facebook currently has a strong interest in React, sees the value of it being Open Source, and this is a huge plus for all the developers using it in their own projects.

Is React simple to learn?

Even though I said that React is simpler than alternative frameworks, diving into React is still complicated, but mostly because of the corollary technologies that can be integrated with React, like Redux and GraphQL.

React in itself has a very small API, and you basically need to understand 4 concepts to get started:

- Components

- JSX

- State

- Props

All these (and more) are explained in this handbook.

How to install React on your development computer

How do you install React?

React is a library, so saying install might sound a bit weird. Maybe setup is a better word, but you get the concept.

There are various ways to setup React so that it can be used on your app or site.

Load React directly in the web page

The simplest one is to add the React JavaScript file into the page directly. This is best when your React app will interact with the elements present on a single page, and not actually controls the whole navigation aspect.

In this case, you add 2 script tags to the end of the body tag:

<html>

...

<body>

...

<script

src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/react/16.8.3/umd/react.development.js"

crossorigin

></script>

<script

src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/react-dom/16.8.3/umd/react-dom.production.min.js"

crossorigin

></script>

</body>

</html>Please change the version number to the latest version of React available.

Here we loaded both React and React DOM. Why 2 libraries? Because React is 100% independent from the browser and can be used outside it (for example on Mobile devices with React Native). Hence the need for React DOM, to add the wrappers for the browser.

After those tags you can load your JavaScript files that use React, or even inline JavaScript in a script tag:

<script src="app.js"></script>

<!-- or -->

<script>

//my app

</script>To use JSX you need an extra step: load Babel

<script src="https://unpkg.com/babel-standalone@6/babel.min.js"></script>and load your scripts with the special text/babel MIME type:

<script src="app.js" type="text/babel"><;/script>Now you can add JSX in your app.js file:

const Button = () => {

return <button>Click me!</button>

}

ReactDOM.render(<Button />, document.getElementById('root'))Check out this simple Glitch example: https://glitch.com/edit/#!/react-example-inline-jsx?path=script.js

Starting in this way with script tags is good for building prototypes and enables a quick start without having to set up a complex workflow.

How to use create-react-app

create-react-app is a project aimed at getting you up to speed with React in no time, and any React app that needs to outgrow a single page will find that create-react-app meets that need.

You start by using npx, which is an easy way to download and execute Node.js commands without installing them. npx comes with npm (since version 5.2) and if you don't have npm installed already, do it now from https://nodejs.org (npm is installed with Node).

If you are unsure which version of npm you have, run npm -v to check if you need to update.

Tip: check out my OSX terminal tutorial if you’re unfamiliar with using the terminal, applies to Linux as well — I’m sorry but I don’t have a tutorial for Windows at the moment, but Google is your friend.

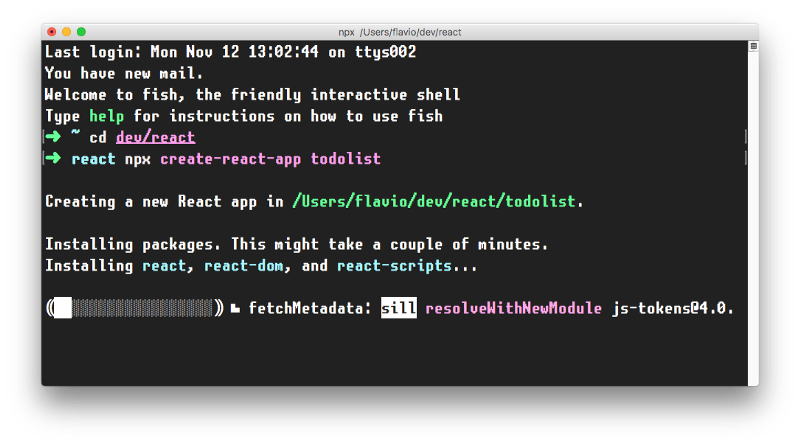

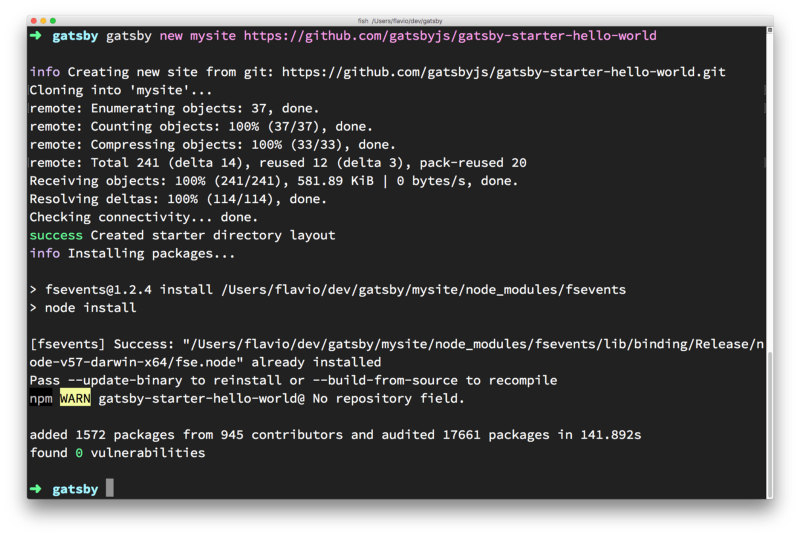

When you run npx create-react-app <app-name>, npx is going to download the most recent create-react-app release, run it, and then remove it from your system. This is great because you will never have an outdated version on your system, and every time you run it, you're getting the latest and greatest code available.

Let’s start then:

npx create-react-app todolist

This is when it finished running:

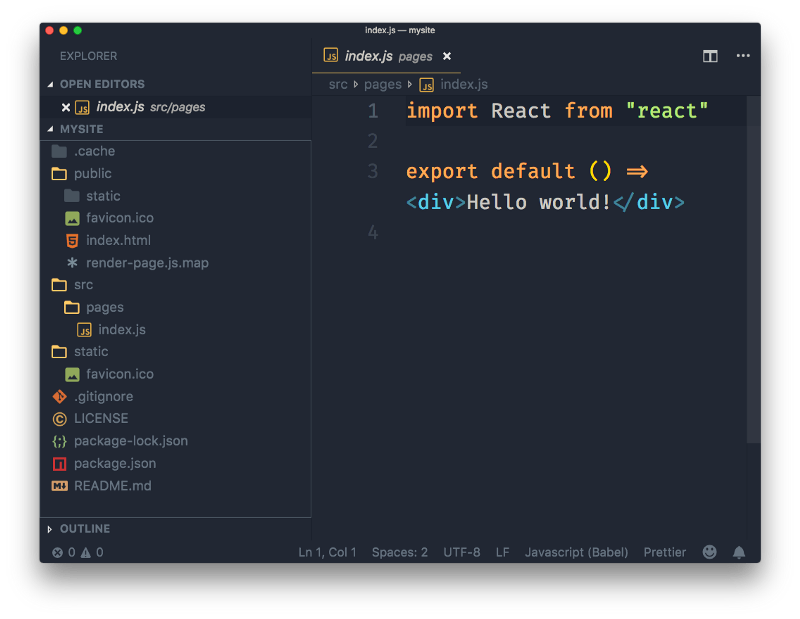

create-react-app created a files structure in the folder you told (todolist in this case), and initialized a Git repository.

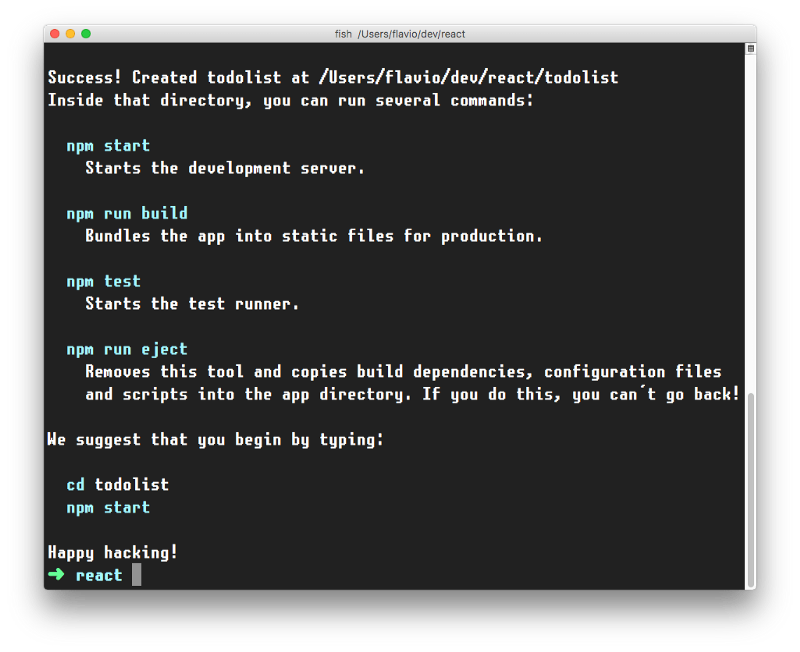

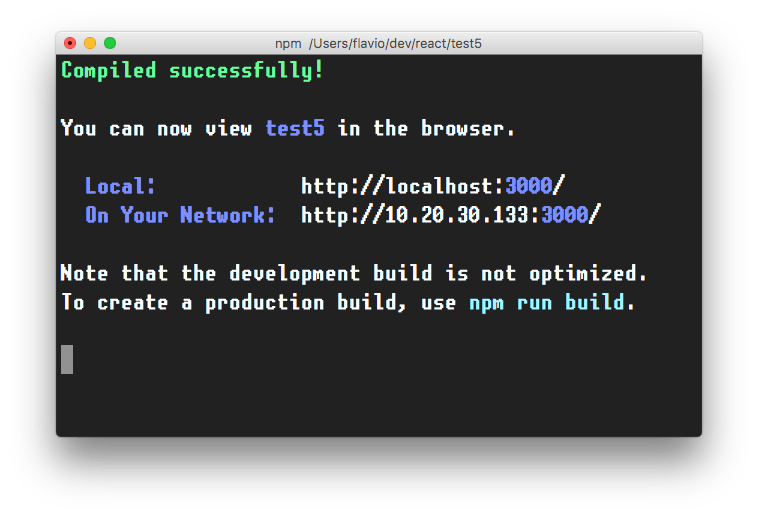

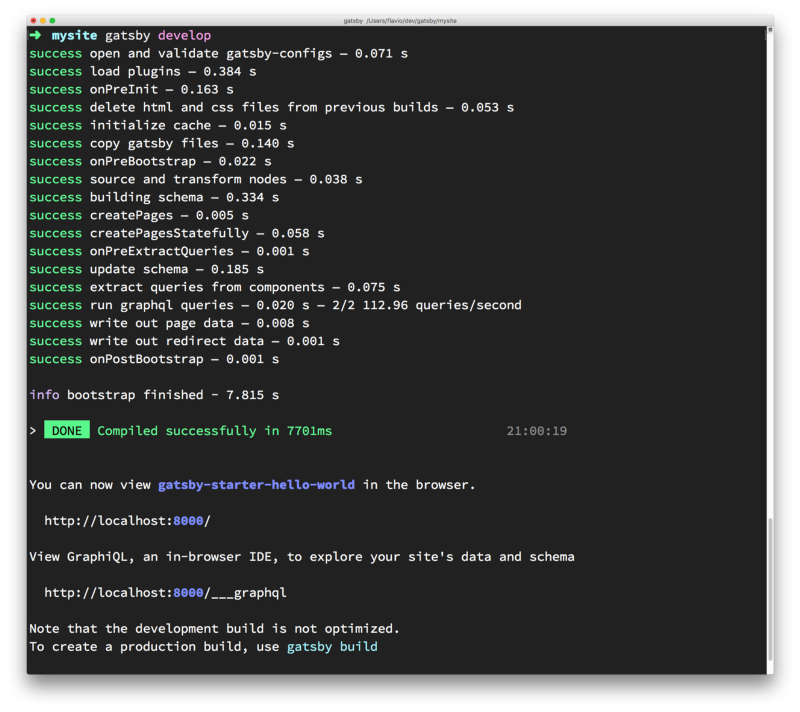

It also added a few commands in the package.json file, so you can immediately start the app by going into the folder and run npm start.

In addition to npm start, create-react-app added a few other commands:

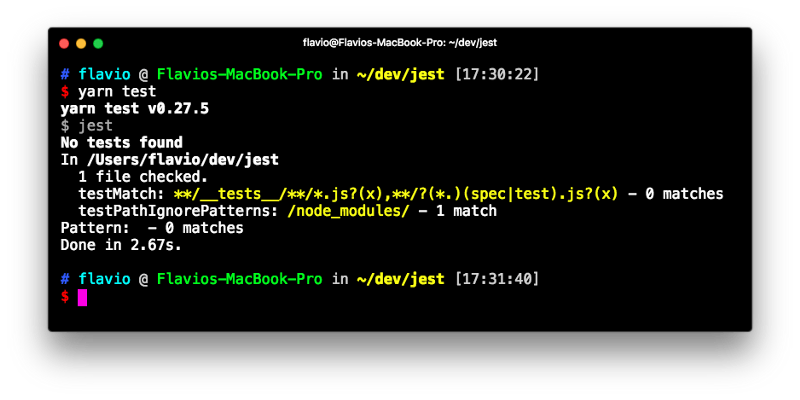

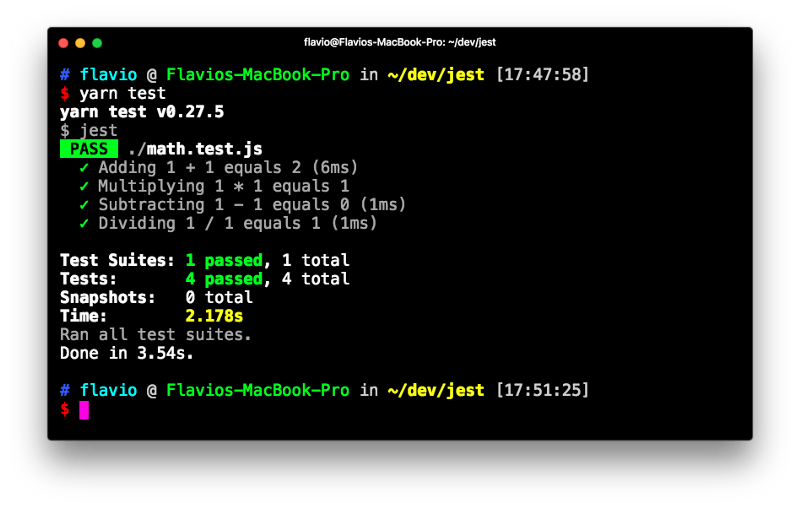

npm run build: to build the React application files in thebuildfolder, ready to be deployed to a servernpm test: to run the testing suite using Jestnpm eject: to eject fromcreate-react-app

Ejecting is the act of deciding that create-react-app has done enough for you, but you want to do more than what it allows.

Since create-react-app is a set of common denominator conventions and a limited amount of options, it's probable that at some point your needs will demand something unique that outgrows the capabilities of create-react-app.

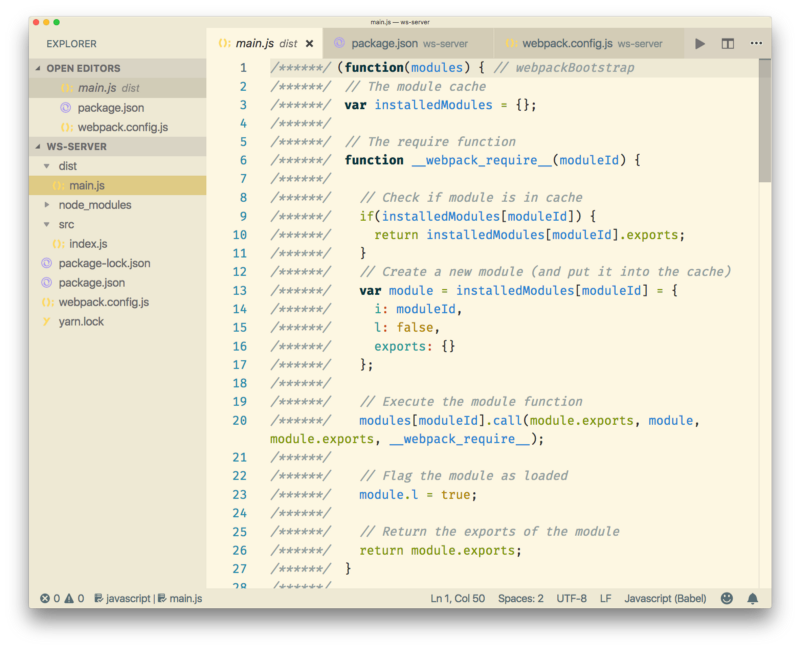

When you eject, you lose the ability of automatic updates but you gain more flexibility in the Babel and Webpack configuration.

When you eject the action is irreversible. You will get 2 new folders in your application directory, config and scripts. Those contain the configurations - and now you can start editing them.

If you already have a React app installed using an older version of React, first check the version by addingconsole.log(React.version)in your app, then you can update by runningyarn add react@16.7, and yarn will prompt you to update (choose the latest version available). Repeat foryarn add react-dom@16.7(change "16.7" with whatever is the newest version of React at the moment)

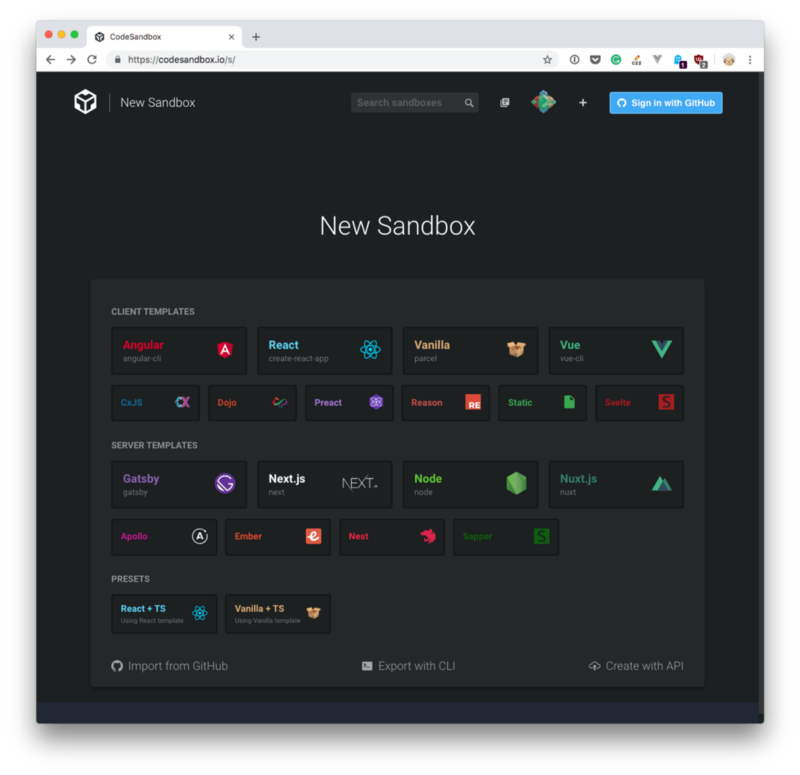

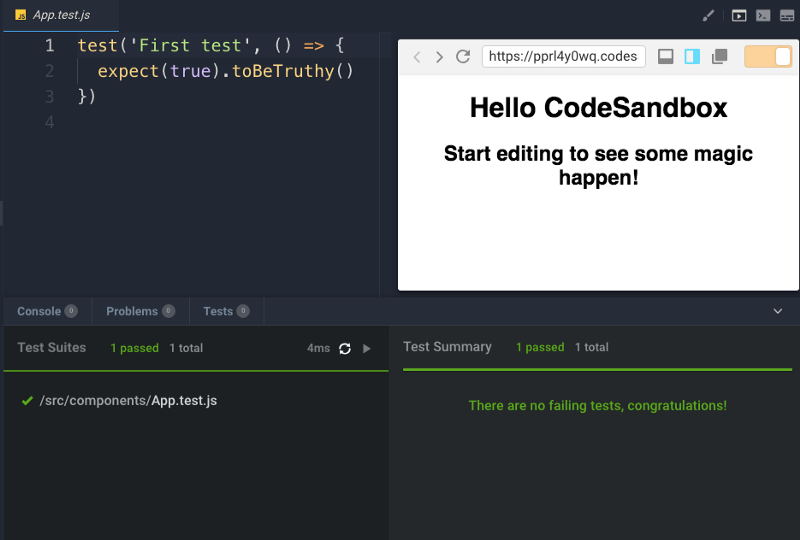

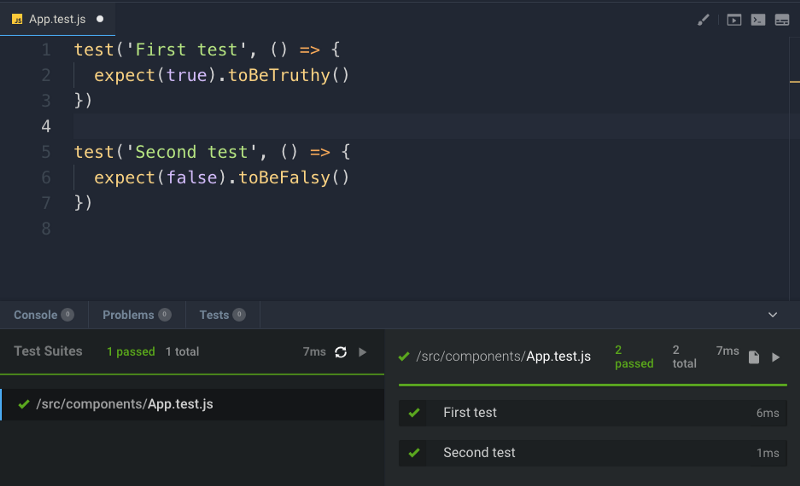

CodeSandbox

An easy way to have the create-react-app structure, without installing it, is to go to https://codesandbox.io/s and choose "React".

CodeSandbox is a great way to start a React project without having to install it locally.

Codepen

Another great solution is Codepen.

You can use this Codepen starter project which already comes pre-configured with React, with support for Hooks: https://codepen.io/flaviocopes/pen/VqeaxB

Codepen “pens” are great for quick projects with one JavaScript file, while “projects” are great for projects with multiple files, like the ones we’ll use the most when building React apps.

One thing to note is that in Codepen, due to how it works internally, you don’t use the regular ES Modules import syntax, but rather to import for example useState, you use

const { useState } = Reactand not

import { useState } from 'react'SECTION 1: MODERN JAVASCRIPT CORE CONCEPTS YOU NEED TO KNOW TO USE REACT

Find out if you have to learn something before diving into learning React

If you are willing to learn React, you first need to have a few things under your belt. There are some prerequisite technologies you have to be familiar with, in particular related to some of the more recent JavaScript features you’ll use over and over in React.

Sometimes people think one particular feature is provided by React, but instead it’s just modern JavaScript syntax.

There is no point in being an expert in those topics right away, but the more you dive into React, the more you’ll need to master those.

I will mention a list of things to get you up to speed quickly.

Variables

A variable is a literal assigned to an identifier, so you can reference and use it later in the program.

Variables in JavaScript do not have any type attached. Once you assign a specific literal type to a variable, you can later reassign the variable to host any other type, without type errors or any issue.

This is why JavaScript is sometimes referred to as “untyped”.

A variable must be declared before you can use it. There are 3 ways to do this, using var, let or const, and those 3 ways differ in how you can interact with the variable later on.

Using var

Until ES2015, var was the only construct available for defining variables.

var a = 0If you forget to add var you will be assigning a value to an undeclared variable, and the results might vary.

In modern environments, with strict mode enabled, you will get an error. In older environments (or with strict mode disabled) this will simply initialize the variable and assign it to the global object.

If you don’t initialize the variable when you declare it, it will have the undefined value until you assign a value to it.

var a //typeof a === 'undefined'You can redeclare the variable many times, overriding it:

var a = 1

var a = 2You can also declare multiple variables at once in the same statement:

var a = 1, b = 2jsxThe scope is the portion of code where the variable is visible.

A variable initialized with var outside of any function is assigned to the global object, has a global scope and is visible everywhere. A variable initialized with var inside a function is assigned to that function, it's local and is visible only inside it, just like a function parameter.

Any variable defined in a function with the same name as a global variable takes precedence over the global variable, shadowing it.

It’s important to understand that a block (identified by a pair of curly braces) does not define a new scope. A new scope is only created when a function is created, because var does not have block scope, but function scope.

Inside a function, any variable defined in it is visible throughout all the function code, even if the variable is declared at the end of the function it can still be referenced in the beginning, because JavaScript before executing the code actually moves all variables on top (something that is called hoisting). To avoid confusion, always declare variables at the beginning of a function.

Using let

let is a new feature introduced in ES2015 and it's essentially a block scoped version of var. Its scope is limited to the block, statement or expression where it's defined, and all the contained inner blocks.

Modern JavaScript developers might choose to only use let and completely discard the use of var.

Ifletseems an obscure term, just readlet color = 'red'as let the color be red and it all makes much more sense

Defining let outside of any function - contrary to var - does not create a global variable.

Using const

Variables declared with var or let can be changed later on in the program, and reassigned. Once a const is initialized, its value can never be changed again, and it can't be reassigned to a different value.

const a = 'test'We can’t assign a different literal to the a const. We can however mutate a if it's an object that provides methods that mutate its contents.

const does not provide immutability, just makes sure that the reference can't be changed.

const has block scope, same as let.

Modern JavaScript developers might choose to always use const for variables that don't need to be reassigned later in the program.

Why? Because we should always use the simplest construct available to avoid making errors down the road.

Arrow functions

Arrow functions were introduced in ES6 / ECMAScript 2015, and since their introduction they changed forever how JavaScript code looks (and works).

In my opinion this change was so welcoming that you now rarely see the usage of the function keyword in modern codebases.

Visually, it’s a simple and welcome change, which allows you to write functions with a shorter syntax, from:

const myFunction = function() {

//...

}to

const myFunction = () => {

//...

}If the function body contains just a single statement, you can omit the brackets and write all on a single line:

const myFunction = () => doSomething()Parameters are passed in the parentheses:

const myFunction = (param1, param2) => doSomething(param1, param2)If you have one (and just one) parameter, you could omit the parentheses completely:

const myFunction = param => doSomething(param)Thanks to this short syntax, arrow functions encourage the use of small functions.

Implicit return

Arrow functions allow you to have an implicit return: values are returned without having to use the return keyword.

It works when there is a one-line statement in the function body:

const myFunction = () => 'test'

myFunction() //'test'Another example, when returning an object, remember to wrap the curly brackets in parentheses to avoid it being considered the wrapping function body brackets:

const myFunction = () => ({ value: 'test' })

myFunction() //{value: 'test'}How this works in arrow functions

this is a concept that can be complicated to grasp, as it varies a lot depending on the context and also varies depending on the mode of JavaScript (strict mode or not).

It’s important to clarify this concept because arrow functions behave very differently compared to regular functions.

When defined as a method of an object, in a regular function this refers to the object, so you can do:

const car = {

model: 'Fiesta',

manufacturer: 'Ford',

fullName: function() {

return `${this.manufacturer} ${this.model}`

}

}calling car.fullName() will return "Ford Fiesta".

The this scope with arrow functions is inherited from the execution context. An arrow function does not bind this at all, so its value will be looked up in the call stack, so in this code car.fullName() will not work, and will return the string "undefined undefined":

const car = {

model: 'Fiesta',

manufacturer: 'Ford',

fullName: () => {

return `${this.manufacturer} ${this.model}`

}

}Due to this, arrow functions are not suited as object methods.

Arrow functions cannot be used as constructors either, when instantiating an object will raise a TypeError.

This is where regular functions should be used instead, when dynamic context is not needed.

This is also a problem when handling events. DOM Event listeners set this to be the target element, and if you rely on this in an event handler, a regular function is necessary:

const link = document.querySelector('#link')

link.addEventListener('click', () => {

// this === window

})

const link = document.querySelector('#link')

link.addEventListener('click', function() {

// this === link

})Rest and spread

You can expand an array, an object or a string using the spread operator ....

Let’s start with an array example. Given

const a = [1, 2, 3]you can create a new array using

const b = [...a, 4, 5, 6]You can also create a copy of an array using

const c = [...a]This works for objects as well. Clone an object with:

const newObj = { ...oldObj }Using strings, the spread operator creates an array with each char in the string:

const hey = 'hey'

const arrayized = [...hey] // ['h', 'e', 'y']This operator has some pretty useful applications. The most important one is the ability to use an array as function argument in a very simple way:

const f = (foo, bar) => {}

const a = [1, 2]

f(...a)(in the past you could do this using f.apply(null, a) but that's not as nice and readable)

The rest element is useful when working with array destructuring:

const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

[first, second, ...others] = numbersand spread elements:

const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

const sum = (a, b, c, d, e) => a + b + c + d + e

const sumOfNumbers = sum(...numbers)ES2018 introduces rest properties, which are the same but for objects.

Rest properties:

const { first, second, ...others } = {

first: 1,

second: 2,

third: 3,

fourth: 4,

fifth: 5

}

first // 1

second // 2

others // { third: 3, fourth: 4, fifth: 5 }Spread properties allow to create a new object by combining the properties of the object passed after the spread operator:

const items = { first, second, ...others }

items //{ first: 1, second: 2, third: 3, fourth: 4, fifth: 5 }Object and array destructuring

Given an object, using the destructuring syntax you can extract just some values and put them into named variables:

const person = {

firstName: 'Tom',

lastName: 'Cruise',

actor: true,

age: 54 //made up

}

const { firstName: name, age } = person //name: Tom, age: 54name and age contain the desired values.

The syntax also works on arrays:

const a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

const [first, second] = aThis statement creates 3 new variables by getting the items with index 0, 1, 4 from the array a:

const [first, second, , , fifth] = aTemplate literals

Template Literals are a new ES2015 / ES6 feature that allows you to work with strings in a novel way compared to ES5 and below.

The syntax at a first glance is very simple, just use backticks instead of single or double quotes:

const a_string = `something`They are unique because they provide a lot of features that normal strings built with quotes do not, in particular:

- they offer a great syntax to define multiline strings

- they provide an easy way to interpolate variables and expressions in strings

- they allow you to create DSLs with template tags (DSL means domain specific language, and it’s for example used in React by Styled Components, to define CSS for a component)

Let’s dive into each of these in detail.

Multiline strings

Pre-ES6, to create a string spanning over two lines you had to use the \ character at the end of a line:

const string =

'first part \

second part'This allows to create a string on 2 lines, but it’s rendered on just one line:

first part second part

To render the string on multiple lines as well, you explicitly need to add \n at the end of each line, like this:

const string =

'first line\n \

second line'or

const string = 'first line\n' + 'second line'Template literals make multiline strings much simpler.

Once a template literal is opened with the backtick, you just press enter to create a new line, with no special characters, and it’s rendered as-is:

const string = `Hey

this

string

is awesome!`Keep in mind that space is meaningful, so doing this:

const string = `First

Second`is going to create a string like this:

First

Secondan easy way to fix this problem is by having an empty first line, and appending the trim() method right after the closing backtick, which will eliminate any space before the first character:

const string = `

First

Second`.trim()Interpolation

Template literals provide an easy way to interpolate variables and expressions into strings.

You do so by using the ${...} syntax:

const myVariable = 'test'

const string = `something ${myVariable}` //something testinside the ${} you can add anything, even expressions:

const string = `something ${1 + 2 + 3}`

const string2 = `something ${foo() ? 'x' : 'y'}`Classes

In 2015 the ECMAScript 6 (ES6) standard introduced classes.

JavaScript has a quite uncommon way to implement inheritance: prototypical inheritance. Prototypal inheritance, while in my opinion great, is unlike most other popular programming language’s implementation of inheritance, which is class-based.

People coming from Java or Python or other languages had a hard time understanding the intricacies of prototypal inheritance, so the ECMAScript committee decided to sprinkle syntactic sugar on top of prototypical inheritance so that it resembles how class-based inheritance works in other popular implementations.

This is important: JavaScript under the hood is still the same, and you can access an object prototype in the usual way.

A class definition

This is how a class looks.

class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name

}

hello() {

return 'Hello, I am ' + this.name + '.'

}

}A class has an identifier, which we can use to create new objects using new ClassIdentifier().

When the object is initialized, the constructor method is called, with any parameters passed.

A class also has as many methods as it needs. In this case hello is a method and can be called on all objects derived from this class:

const flavio = new Person('Flavio')

flavio.hello()Class inheritance

A class can extend another class, and objects initialized using that class inherit all the methods of both classes.

If the inherited class has a method with the same name as one of the classes higher in the hierarchy, the closest method takes precedence:

class Programmer extends Person {

hello() {

return super.hello() + ' I am a programmer.'

}

}

const flavio = new Programmer('Flavio')

flavio.hello()(the above program prints “Hello, I am Flavio. I am a programmer.”)

Classes do not have explicit class variable declarations, but you must initialize any variable in the constructor.

Inside a class, you can reference the parent class calling super().

Static methods

Normally methods are defined on the instance, not on the class.

Static methods are executed on the class instead:

class Person {

static genericHello() {

return 'Hello'

}

}

Person.genericHello() //HelloPrivate methods

JavaScript does not have a built-in way to define private or protected methods.

There are workarounds, but I won’t describe them here.

Getters and setters

You can add methods prefixed with get or set to create a getter and setter, which are two different pieces of code that are executed based on what you are doing: accessing the variable, or modifying its value.

class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name

}

set name(value) {

this.name = value

}

get name() {

return this.name

}

}If you only have a getter, the property cannot be set, and any attempt at doing so will be ignored:

class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name

}

get name() {

return this.name

}

}If you only have a setter, you can change the value but not access it from the outside:

class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name

}

set name(value) {

this.name = value

}

}Callbacks

Computers are asynchronous by design.

Asynchronous means that things can happen independently of the main program flow.

In the current consumer computers, every program runs for a specific time slot, and then it stops its execution to let another program continue its execution. This thing runs in a cycle so fast that’s impossible to notice, and we think our computers run many programs simultaneously, but this is an illusion (except on multiprocessor machines).

Programs internally use interrupts, a signal that’s emitted to the processor to gain the attention of the system.

I won’t go into the internals of this, but just keep in mind that it’s normal for programs to be asynchronous, and halt their execution until they need attention, and the computer can execute other things in the meantime. When a program is waiting for a response from the network, it cannot halt the processor until the request finishes.

Normally, programming languages are synchronous, and some provide a way to manage asynchronicity, in the language or through libraries. C, Java, C#, PHP, Go, Ruby, Swift, Python, they are all synchronous by default. Some of them handle async by using threads, spawning a new process.

JavaScript is synchronous by default and is single threaded. This means that code cannot create new threads and run in parallel.

Lines of code are executed in series, one after another, for example:

const a = 1

const b = 2

const c = a * b

console.log(c)

doSomething()But JavaScript was born inside the browser, its main job, in the beginning, was to respond to user actions, like onClick, onMouseOver, onChange, onSubmit and so on. How could it do this with a synchronous programming model?

The answer was in its environment. The browser provides a way to do it by providing a set of APIs that can handle this kind of functionality.

More recently, Node.js introduced a non-blocking I/O environment to extend this concept to file access, network calls and so on.

You can’t know when a user is going to click a button, so what you do is, you define an event handler for the click event. This event handler accepts a function, which will be called when the event is triggered:

document.getElementById('button').addEventListener('click', () => {

//item clicked

})This is the so-called callback.

A callback is a simple function that’s passed as a value to another function, and will only be executed when the event happens. We can do this because JavaScript has first-class functions, which can be assigned to variables and passed around to other functions (called higher-order functions)

It’s common to wrap all your client code in a load event listener on the windowobject, which runs the callback function only when the page is ready:

window.addEventListener('load', () => {

//window loaded

//do what you want

})Callbacks are used everywhere, not just in DOM events.

One common example is by using timers:

setTimeout(() => {

// runs after 2 seconds

}, 2000)XHR requests also accept a callback, in this example by assigning a function to a property that will be called when a particular event occurs (in this case, the state of the request changes):

const xhr = new XMLHttpRequest()

xhr.onreadystatechange = () => {

if (xhr.readyState === 4) {

xhr.status === 200 ? console.log(xhr.responseText) : console.error('error')

}

}

xhr.open('GET', 'https://yoursite.com')

xhr.send()Handling errors in callbacks

How do you handle errors with callbacks? One very common strategy is to use what Node.js adopted: the first parameter in any callback function is the error object: error-first callbacks

If there is no error, the object is null. If there is an error, it contains some description of the error and other information.

fs.readFile('/file.json', (err, data) => {

if (err !== null) {

//handle error

console.log(err)

return

}

//no errors, process data

console.log(data)

})The problem with callbacks

Callbacks are great for simple cases!

However every callback adds a level of nesting, and when you have lots of callbacks, the code starts to be complicated very quickly:

window.addEventListener('load', () => {

document.getElementById('button').addEventListener('click', () => {

setTimeout(() => {

items.forEach(item => {

//your code here

})

}, 2000)

})

})This is just a simple 4-levels code, but I’ve seen much more levels of nesting and it’s not fun.

How do we solve this?

ALTERNATIVES TO CALLBACKS

Starting with ES6, JavaScript introduced several features that help us with asynchronous code that do not involve using callbacks:

- Promises (ES6)

- Async/Await (ES8)

Promises

Promises are one way to deal with asynchronous code, without writing too many callbacks in your code.

Although they’ve been around for years, they were standardized and introduced in ES2015, and now they have been superseded in ES2017 by async functions.

Async functions use the promises API as their building block, so understanding them is fundamental even if in newer code you’ll likely use async functions instead of promises.

How promises work, in brief

Once a promise has been called, it will start in pending state. This means that the caller function continues the execution, while it waits for the promise to do its own processing, and give the caller function some feedback.

At this point, the caller function waits for it to either return the promise in a resolved state, or in a rejected state, but as you know JavaScript is asynchronous, so the function continues its execution while the promise does it work.

Which JS API use promises?

In addition to your own code and library code, promises are used by standard modern Web APIs like Fetch or Service Workers.

It’s unlikely that in modern JavaScript you’ll find yourself not using promises, so let’s start diving right into them.

Creating a promise

The Promise API exposes a Promise constructor, which you initialize using new Promise():

let done = true

const isItDoneYet = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

if (done) {

const workDone = 'Here is the thing I built'

resolve(workDone)

} else {

const why = 'Still working on something else'

reject(why)

}

})As you can see the promise checks the done global constant, and if that's true, we return a resolved promise, otherwise a rejected promise.

Using resolve and reject we can communicate back a value, in the above case we just return a string, but it could be an object as well.

Consuming a promise

In the last section, we introduced how a promise is created.

Now let’s see how the promise can be consumed or used.

const isItDoneYet = new Promise()

//...

const checkIfItsDone = () => {

isItDoneYet

.then(ok => {

console.log(ok)

})

.catch(err => {

console.error(err)

})

}Running checkIfItsDone() will execute the isItDoneYet() promise and will wait for it to resolve, using the then callback, and if there is an error, it will handle it in the catch callback.

Chaining promises

A promise can be returned to another promise, creating a chain of promises.

A great example of chaining promises is given by the Fetch API, a layer on top of the XMLHttpRequest API, which we can use to get a resource and queue a chain of promises to execute when the resource is fetched.

The Fetch API is a promise-based mechanism, and calling fetch() is equivalent to defining our own promise using new Promise().

Example:

const status = response => {

if (response.status >= 200 && response.status < 300) {

return Promise.resolve(response)

}

return Promise.reject(new Error(response.statusText))

}

const json = response => response.json()

fetch('/todos.json')

.then(status)

.then(json)

.then(data => {

console.log('Request succeeded with JSON response', data)

})

.catch(error => {

console.log('Request failed', error)

})In this example, we call fetch() to get a list of TODO items from the todos.json file found in the domain root, and we create a chain of promises.

Running fetch() returns a response, which has many properties, and within those we reference:

status, a numeric value representing the HTTP status codestatusText, a status message, which isOKif the request succeeded

response also has a json() method, which returns a promise that will resolve with the content of the body processed and transformed into JSON.

So given those premises, this is what happens: the first promise in the chain is a function that we defined, called status(), that checks the response status and if it's not a success response (between 200 and 299), it rejects the promise.

This operation will cause the promise chain to skip all the chained promises listed and will skip directly to the catch() statement at the bottom, logging the Request failed text along with the error message.

If that succeeds instead, it calls the json() function we defined. Since the previous promise, when successful, returned the response object, we get it as an input to the second promise.

In this case, we return the data JSON processed, so the third promise receives the JSON directly:

.then((data) => {

console.log('Request succeeded with JSON response', data)

})and we simply log it to the console.

Handling errors

In the above example, in the previous section, we had a catch that was appended to the chain of promises.

When anything in the chain of promises fails and raises an error or rejects the promise, the control goes to the nearest catch() statement down the chain.

new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

throw new Error('Error')

}).catch(err => {

console.error(err)

})

// or

new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

reject('Error')

}).catch(err => {

console.error(err)

})Cascading errors

If inside the catch() you raise an error, you can append a second catch() to handle it, and so on.

new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

throw new Error('Error')

})

.catch(err => {

throw new Error('Error')

})

.catch(err => {

console.error(err)

})Orchestrating promises with Promise.all()

If you need to synchronize different promises, Promise.all() helps you define a list of promises, and execute something when they are all resolved.

Example:

const f1 = fetch('/something.json')

const f2 = fetch('/something2.json')

Promise.all([f1, f2])

.then(res => {

console.log('Array of results', res)

})

.catch(err => {

console.error(err)

})The ES2015 destructuring assignment syntax allows you to also do

Promise.all([f1, f2]).then(([res1, res2]) => {

console.log('Results', res1, res2)

})You are not limited to using fetch of course, any promise is good to go.

Orchestrating promises with Promise.race()

Promise.race() runs as soon as one of the promises you pass to it resolves, and it runs the attached callback just once with the result of the first promise resolved.

Example:

const promiseOne = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 500, 'one')

})

const promiseTwo = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 100, 'two')

})

Promise.race([promiseOne, promiseTwo]).then(result => {

console.log(result) // 'two'

})Async/Await

JavaScript evolved in a very short time from callbacks to promises (ES2015), and since ES2017 asynchronous JavaScript is even simpler with the async/await syntax.

Async functions are a combination of promises and generators, and basically, they are a higher level abstraction over promises. Let me repeat: async/await is built on promises.

Why were async/await introduced?

They reduce the boilerplate around promises, and the “don’t break the chain” limitation of chaining promises.

When Promises were introduced in ES2015, they were meant to solve a problem with asynchronous code, and they did, but over the 2 years that separated ES2015 and ES2017, it was clear that promises could not be the final solution.

Promises were introduced to solve the famous callback hell problem, but they introduced complexity on their own, and syntax complexity.

They were good primitives around which a better syntax could be exposed to developers, so when the time was right we got async functions.

They make the code look like it’s synchronous, but it’s asynchronous and non-blocking behind the scenes.

How it works

An async function returns a promise, like in this example:

const doSomethingAsync = () => {

return new Promise(resolve => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('I did something'), 3000)

})

}When you want to call this function you prepend await, and the calling code will stop until the promise is resolved or rejected. One caveat: the client function must be defined as async. Here's an example:

const doSomething = async () => {

console.log(await doSomethingAsync())

}A quick example

This is a simple example of async/await used to run a function asynchronously:

const doSomethingAsync = () => {

return new Promise(resolve => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('I did something'), 3000)

})

}

const doSomething = async () => {

console.log(await doSomethingAsync())

}

console.log('Before')

doSomething()

console.log('After')The above code will print the following to the browser console:

Before

After

I did something //after 3sPromise all the things

Prepending the async keyword to any function means that the function will return a promise.

Even if it’s not doing so explicitly, it will internally make it return a promise.

This is why this code is valid:

const aFunction = async () => {

return 'test'

}

aFunction().then(alert) // This will alert 'test'and it’s the same as:

const aFunction = async () => {

return Promise.resolve('test')

}

aFunction().then(alert) // This will alert 'test'The code is much simpler to read

As you can see in the example above, our code looks very simple. Compare it to code using plain promises, with chaining and callback functions.

And this is a very simple example, the major benefits will arise when the code is much more complex.

For example here’s how you would get a JSON resource, and parse it, using promises:

const getFirstUserData = () => {

return fetch('/users.json') // get users list

.then(response => response.json()) // parse JSON

.then(users => users[0]) // pick first user

.then(user => fetch(`/users/${user.name}`)) // get user data

.then(userResponse => userResponse.json()) // parse JSON

}

getFirstUserData()And here is the same functionality provided using await/async:

const getFirstUserData = async () => {

const response = await fetch('/users.json') // get users list

const users = await response.json() // parse JSON

const user = users[0] // pick first user

const userResponse = await fetch(`/users/${user.name}`) // get user data

const userData = await userResponse.json() // parse JSON

return userData

}

getFirstUserData()Multiple async functions in series

Async functions can be chained very easily, and the syntax is much more readable than with plain promises:

const promiseToDoSomething = () => {

return new Promise(resolve => {

setTimeout(() => resolve('I did something'), 10000)

})

}

const watchOverSomeoneDoingSomething = async () => {

const something = await promiseToDoSomething()

return something + ' and I watched'

}

const watchOverSomeoneWatchingSomeoneDoingSomething = async () => {

const something = await watchOverSomeoneDoingSomething()

return something + ' and I watched as well'

}

watchOverSomeoneWatchingSomeoneDoingSomething().then(res => {

console.log(res)

})Will print:

I did something and I watched and I watched as wellEasier debugging

Debugging promises is hard because the debugger will not step over asynchronous code.

Async/await makes this very easy because to the compiler it’s just like synchronous code.

ES Modules

ES Modules is the ECMAScript standard for working with modules.

While Node.js has been using the CommonJS standard for years, the browser never had a module system, as every major decision such as a module system must be first standardized by ECMAScript and then implemented by the browser.

This standardization process completed with ES6 and browsers started implementing this standard trying to keep everything well aligned, working all in the same way, and now ES Modules are supported in Chrome, Safari, Edge and Firefox (since version 60).

Modules are very cool, because they let you encapsulate all sorts of functionality, and expose this functionality to other JavaScript files, as libraries.

The ES Modules Syntax

The syntax to import a module is:

import package from 'module-name'while CommonJS uses

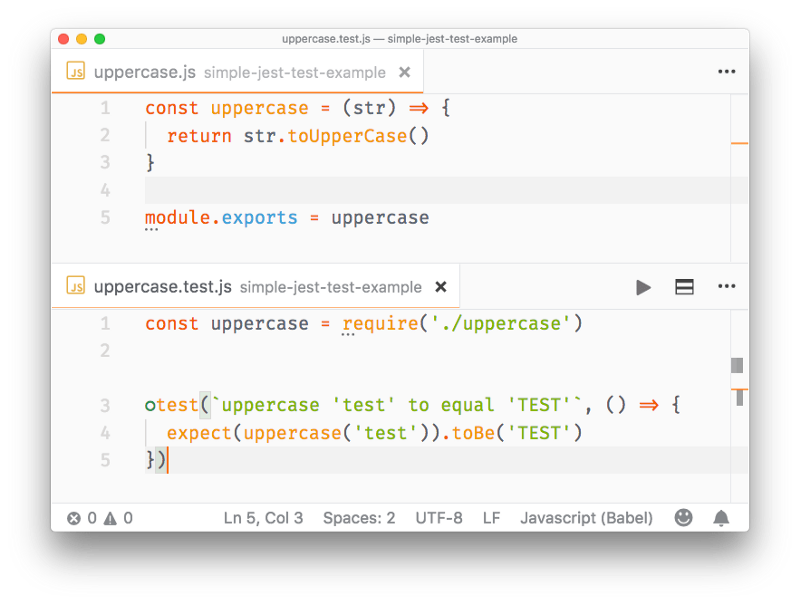

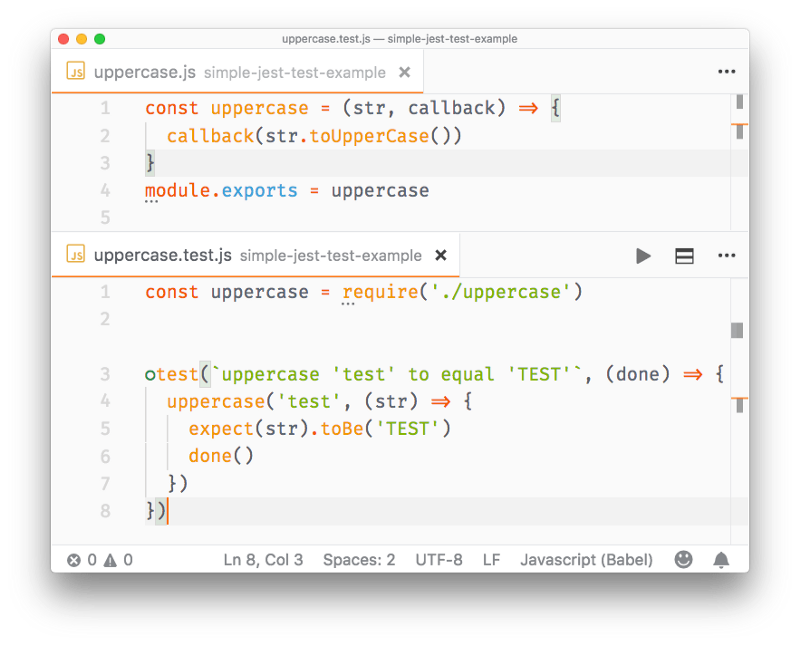

const package = require('module-name')A module is a JavaScript file that exports one or more values (objects, functions or variables), using the export keyword. For example, this module exports a function that returns a string uppercase:

uppercase.js

export default str => str.toUpperCase()In this example, the module defines a single, default export, so it can be an anonymous function. Otherwise it would need a name to distinguish it from other exports.

Now, any other JavaScript module can import the functionality offered by uppercase.js by importing it.

An HTML page can add a module by using a <script> tag with the special type="module" attribute:

<script type="module" src="index.js"><;/script>Note: this module import behaves like a defer script load. See efficiently load JavaScript with defer and asyncIt’s important to note that any script loaded with type="module" is loaded in strict mode.

In this example, the uppercase.js module defines a default export, so when we import it, we can assign it a name we prefer:

import toUpperCase from './uppercase.js'and we can use it:

toUpperCase('test') //'TEST'You can also use an absolute path for the module import, to reference modules defined on another domain:

import toUpperCase from 'https://flavio-es-modules-example.glitch.me/uppercase.js'This is also valid import syntax:

import { foo } from '/uppercase.js'import { foo } from '../uppercase.js'This is not:

import { foo } from 'uppercase.js'

import { foo } from 'utils/uppercase.js'It’s either absolute, or has a ./ or / before the name.

Other import/export options

We saw this example above:

export default str => str.toUpperCase()This creates one default export. In a file however you can export more than one thing, by using this syntax:

const a = 1

const b = 2

const c = 3

export { a, b, c }Another module can import all those exports using

import * from 'module'You can import just a few of those exports, using the destructuring assignment:

import { a } from 'module'

import { a, b } from 'module'You can rename any import, for convenience, using as:

import { a, b as two } from 'module'You can import the default export, and any non-default export by name, like in this common React import:

import React, { Component } from 'react'You can see an ES Modules example here: https://glitch.com/edit/#!/flavio-es-modules-example?path=index.html

CORS

Modules are fetched using CORS. This means that if you reference scripts from other domains, they must have a valid CORS header that allows cross-site loading (like Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *)

What about browsers that do not support modules?

Use a combination of type="module" and nomodule:

<script type="module" src="module.js"></script>

<script nomodule src="fallback.js"></script>ES Modules are one of the biggest features introduced in modern browsers. They are part of ES6 but the road to implement them has been long.

We can now use them! But we must also remember that having more than a few modules is going to have a performance hit on our pages, as it’s one more step that the browser must perform at runtime.

Webpack is probably going to still be a huge player even if ES Modules land in the browser, but having such a feature directly built in the language is huge for a unification of how modules work client-side and on Node.js as well.

SECTION 2: REACT CONCEPTS

Single Page Applications

React Applications are also called Single Page Applications. What does this mean?

In the past, when browsers were much less capable than today, and JavaScript performance was poor, every page was coming from a server. Every time you clicked something, a new request was made to the server and the browser subsequently loaded the new page.

Only very innovative products worked differently, and experimented with new approaches.

Today, popularized by modern frontend JavaScript frameworks like React, an app is usually built as a single page application: you only load the application code (HTML, CSS, JavaScript) once, and when you interact with the application, what generally happens is that JavaScript intercepts the browser events and instead of making a new request to the server that then returns a new document, the client requests some JSON or performs an action on the server but the page that the user sees is never completely wiped away, and behaves more like a desktop application.

Single page applications are built in JavaScript (or at least compiled to JavaScript) and work in the browser.

The technology is always the same, but the philosophy and some key components of how the application works are different.

Examples of Single Page Applications

Some notable examples:

- Gmail

- Google Maps

- Google Drive

Pros and cons of SPAs

An SPA feels much faster to the user, because instead of waiting for the client-server communication to happen, and wait for the browser to re-render the page, you can now have instant feedback. This is the responsibility of the application maker, but you can have transitions and spinners and any kind of UX improvement that is certainly better than the traditional workflow.

In addition to making the experience faster to the user, the server will consume less resources because you can focus on providing an efficient API instead of building the layouts server-side.

This makes it ideal if you also build a mobile app on top of the API, as you can completely reuse your existing server-side code.

Single Page Applications are easy to transform into Progressive Web Apps, which in turn enables you to provide local caching and to support offline experiences for your services (or simply a better error message if your users need to be online).

SPAs are best used when there is no need for SEO (search engine optimization). For example for apps that work behind a login.

Search engines, while improving every day, still have trouble indexing sites built with an SPA approach rather than the traditional server-rendered pages. This is the case for blogs. If you are going to rely on search engines, don’t even bother with creating a single page application without having a server rendered part as well.

When coding an SPA, you are going to write a great deal of JavaScript. Since the app can be long-running, you are going to need to pay a lot more attention to possible memory leaks — if in the past your page had a lifespan that was counted in minutes, now an SPA might stay open for hours at a time and if there is any memory issue that’s going to increase the browser memory usage by a lot more and it’s going to cause an unpleasantly slow experience if you don’t take care of it.

SPAs are great when working in teams. Backend developers can just focus on the API, and frontend developers can focus on creating the best user experience, making use of the API built in the backend.

As a con, Single Page Apps rely heavily on JavaScript. This might make using an application running on low power devices a poor experience in terms of speed. Also, some of your visitors might just have JavaScript disabled, and you also need to consider accessibility for anything you build.

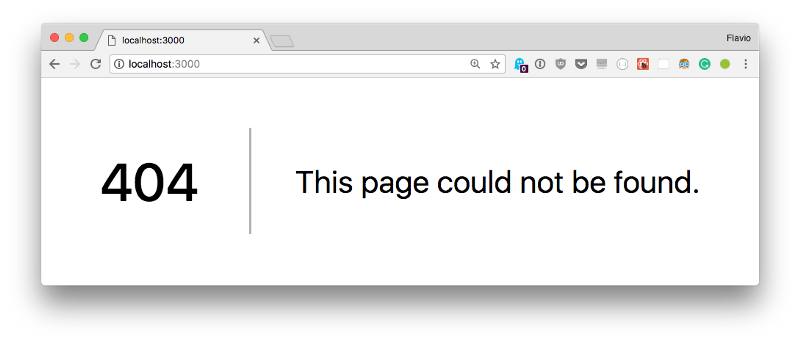

Overriding the navigation

Since you get rid of the default browser navigation, URLs must be managed manually.

This part of an application is called the router. Some frameworks already take care of them for you (like Ember), others require libraries that will do this job (like React Router).

What’s the problem? In the beginning, this was an afterthought for developers building Single Page Applications. This caused the common “broken back button” issue: when navigating inside the application the URL didn’t change (since the browser default navigation was hijacked) and hitting the back button, a common operation that users do to go to the previous screen, might move to a website you visited a long time ago.

This problem can now be solved using the History API offered by browsers, but most of the time you’ll use a library that internally uses that API, like React Router.

Declarative

What does it mean when you read that React is declarative? You’ll run across articles describing React as a declarative approach to building UIs.

React made its “declarative approach” quite popular and upfront so it permeated the frontend world along with React.

It’s really not a new concept, but React took building UIs a lot more declaratively than with HTML templates:

- you can build Web interfaces without even touching the DOM directly

- you can have an event system without having to interact with the actual DOM Events.

The opposite of declarative is imperative. A common example of an imperative approach is looking up elements in the DOM using jQuery or DOM events. You tell the browser exactly what to do, instead of telling it what you need.

The React declarative approach abstracts that for us. We just tell React we want a component to be rendered in a specific way, and we never have to interact with the DOM to reference it later.

Immutability

One concept you will likely meet when programming in React is immutability (and its opposite, mutability).

It’s a controversial topic, but whatever you might think about the concept of immutability, React and most of its ecosystem kind of forces this, so you need to at least have a grasp of why it’s so important and the implications of it.

In programming, a variable is immutable when its value cannot change after it’s created.

You are already using immutable variables without knowing it when you manipulate a string. Strings are immutable by default, when you change them in reality you create a new string and assign it to the same variable name.

An immutable variable can never be changed. To update its value, you create a new variable.

The same applies to objects and arrays.

Instead of changing an array, to add a new item you create a new array by concatenating the old array, plus the new item.

An object is never updated, but copied before changing it.

This applies to React in many places.

For example, you should never mutate the state property of a component directly, but only through the setState() method.

In Redux, you never mutate the state directly, but only through reducers, which are functions.

The question is, why?

There are various reasons, the most important of which are:

- Mutations can be centralized, like in the case of Redux, which improves your debugging capabilities and reduces sources of errors.

- Code looks cleaner and simpler to understand. You never expect a function to change some value without you knowing, which gives you predictability. When a function does not mutate objects but just returns a new object, it’s called a pure function.

- The library can optimize the code because for example JavaScript is faster when swapping an old object reference for an entirely new object, rather than mutating an existing object. This gives you performance.

Purity

In JavaScript, when a function does not mutate objects but just returns a new object, it’s called a pure function.

A function, or a method, in order to be called pure should not cause side effects and should return the same output when called multiple times with the same input.

A pure function takes an input and returns an output without changing the input nor anything else.

Its output is only determined by the arguments. You could call this function 1M times, and given the same set of arguments, the output will always be the same.

React applies this concept to components. A React component is a pure component when its output is only dependant on its props.

All functional components are pure components:

const Button = props => {

return <button>{props.message}</button>

}Class components can be pure if their output only depends on the props:

class Button extends React.Component {

render() {

return <button>{this.props.message}</button>

}

}Composition

In programming, composition allows you to build more complex functionality by combining small and focused functions.

For example, think about using map() to create a new array from an initial set, and then filtering the result using filter():

const list = ['Apple', 'Orange', 'Egg']

list.map(item => item[0]).filter(item => item === 'A') //'A'In React, composition allows you to have some pretty cool advantages.

You create small and lean components and use them to compose more functionality on top of them. How?

Create specialized version of a component

Use an outer component to expand and specialize a more generic component:

const Button = props => {

return <button>{props.text}</button>

}

const SubmitButton = () => {

return <Button text="Submit" />

}

const LoginButton = () => {

return <Button text="Login" />

}Pass methods as props

A component can focus on tracking a click event, for example, and what actually happens when the click event happens is up to the container component:

const Button = props => {

return <button onClick={props.onClickHandler}>{props.text}</button>

}

const LoginButton = props => {

return <Button text="Login" onClickHandler={props.onClickHandler} />

}

const Container = () => {

const onClickHandler = () => {

alert('clicked')

}

return <LoginButton onClickHandler={onClickHandler} />

}Using children

The props.children property allows you to inject components inside other components.

The component needs to output props.children in its JSX:

const Sidebar = props => {

return <aside>{props.children}</aside>

}and you embed more components into it in a transparent way:

<Sidebar>

<Link title="First link" />

<Link title="Second link" />

</Sidebar>Higher order components

When a component receives a component as a prop and returns a component, it’s called higher order component.

We’ll see them in a little while.

The Virtual DOM

Many existing frameworks, before React came on the scene, were directly manipulating the DOM on every change.

First, what is the DOM?

The DOM (Document Object Model) is a Tree representation of the page, starting from the <html> tag, going down into every child, which are called nodes.

It’s kept in the browser memory, and directly linked to what you see in a page. The DOM has an API that you can use to traverse it, access every single node, filter them, modify them.

The API is the familiar syntax you have likely seen many times, if you were not using the abstract API provided by jQuery and friends:

document.getElementById(id)

document.getElementsByTagName(name)

document.createElement(name)

parentNode.appendChild(node)

element.innerHTML

element.style.left

element.setAttribute()

element.getAttribute()

element.addEventListener()

window.content

window.onload

window.dump()

window.scrollTo()React keeps a copy of the DOM representation, for what concerns the React rendering: the Virtual DOM

The Virtual DOM Explained

Every time the DOM changes, the browser has to do two intensive operations: repaint (visual or content changes to an element that do not affect the layout and positioning relative to other elements) and reflow (recalculate the layout of a portion of the page — or the whole page layout).

React uses a Virtual DOM to help the browser use less resources when changes need to be done on a page.

When you call setState() on a Component, specifying a state different than the previous one, React marks that Component as dirty. This is key: React only updates when a Component changes the state explicitly.

What happens next is:

- React updates the Virtual DOM relative to the components marked as dirty (with some additional checks, like triggering

shouldComponentUpdate()) - Runs the diffing algorithm to reconcile the changes

- Updates the real DOM

Why is the Virtual DOM helpful: batching

The key thing is that React batches much of the changes and performs a unique update to the real DOM, by changing all the elements that need to be changed at the same time, so the repaint and reflow the browser must perform to render the changes are executed just once.

Unidirectional Data Flow

Working with React you might encounter the term Unidirectional Data Flow. What does it mean? Unidirectional Data Flow is not a concept unique to React, but as a JavaScript developer this might be the first time you hear it.

In general this concept means that data has one, and only one, way to be transferred to other parts of the application.

In React this means that:

- state is passed to the view and to child components

- actions are triggered by the view

- actions can update the state

- the state change is passed to the view and to child components

The view is a result of the application state. State can only change when actions happen. When actions happen, the state is updated.

Thanks to one-way bindings, data cannot flow in the opposite way (as would happen with two-way bindings, for example), and this has some key advantages:

- it’s less error prone, as you have more control over your data

- it’s easier to debug, as you know what is coming from where

- it’s more efficient, as the library already knows what the boundaries are of each part of the system

A state is always owned by one Component. Any data that’s affected by this state can only affect Components below it: its children.

Changing state on a Component will never affect its parent, or its siblings, or any other Component in the application: just its children.

This is the reason that the state is often moved up in the Component tree, so that it can be shared between components that need to access it.

SECTION 3: IN-DEPTH REACT

JSX

JSX is a technology that was introduced by React.

Although React can work completely fine without using JSX, it’s an ideal technology to work with components, so React benefits a lot from JSX.

At first, you might think that using JSX is like mixing HTML and JavaScript (and as you’ll see CSS).

But this is not true, because what you are really doing when using JSX syntax is writing a declarative syntax of what a component UI should be.

And you’re describing that UI not using strings, but instead using JavaScript, which allows you to do many nice things.

A JSX primer

Here is how you define a h1 tag containing a string:

const element = <h1>Hello, world!</h1>It looks like a strange mix of JavaScript and HTML, but in reality it’s all JavaScript.

What looks like HTML, is actually syntactic sugar for defining components and their positioning inside the markup.

Inside a JSX expression, attributes can be inserted very easily:

const myId = 'test'

const element = <h1 id={myId}>Hello, world!</h1>You just need to pay attention when an attribute has a dash (-) which is converted to camelCase syntax instead, and these 2 special cases:

classbecomesclassNameforbecomeshtmlFor

because they are reserved words in JavaScript.

Here’s a JSX snippet that wraps two components into a div tag:

<div>

<BlogPostsList />

<Sidebar />

</div>A tag always needs to be closed, because this is more XML than HTML (if you remember the XHTML days, this will be familiar, but since then the HTML5 loose syntax won). In this case a self-closing tag is used.

Notice how I wrapped the 2 components into a div. Why? Because the render() function can only return a single node, so in case you want to return 2 siblings, just add a parent. It can be any tag, not just div.

Transpiling JSX

A browser cannot execute JavaScript files containing JSX code. They must be first transformed to regular JS.

How? By doing a process called transpiling.

We already said that JSX is optional, because to every JSX line, a corresponding plain JavaScript alternative is available, and that’s what JSX is transpiled to.

For example the following two constructs are equivalent:

Plain JS

ReactDOM.render(

React.DOM.div(

{ id: 'test' },

React.DOM.h1(null, 'A title'),

React.DOM.p(null, 'A paragraph')

),

document.getElementById('myapp')

)JSX

ReactDOM.render(

<div id="test">

<h1>A title</h1>

<p>A paragraph</p>

</div>,

document.getElementById('myapp')

)This very basic example is just the starting point, but you can already see how more complicated the plain JS syntax is compared to using JSX.

At the time of writing the most popular way to perform the transpilation is to use Babel, which is the default option when running create-react-app, so if you use it you don't have to worry, everything happens under the hood for you.

If you don’t use create-react-app you need to setup Babel yourself.

JS in JSX

JSX accepts any kind of JavaScript mixed into it.

Whenever you need to add some JS, just put it inside curly braces {}. For example here's how to use a constant value defined elsewhere:

const paragraph = 'A paragraph'

ReactDOM.render(

<div id="test">

<h1>A title</h1>

<p>{paragraph}</p>

</div>,

document.getElementById('myapp')

)This is a basic example. Curly braces accept any JS code:

const paragraph = 'A paragraph'

ReactDOM.render(

<table>

{rows.map((row, i) => {

return <tr>{row.text}</tr>

})}

</table>,

document.getElementById('myapp')

)As you can see we nested JavaScript inside JSX defined inside JavaScript nested in JSX. You can go as deep as you need.

HTML in JSX

JSX resembles HTML a lot, but it’s actually XML syntax.

In the end you render HTML, so you need to know a few differences between how you would define some things in HTML, and how you define them in JSX.

You need to close all tags

Just like in XHTML, if you have ever used it, you need to close all tags: no more <br> but instead use the self-closing tag: <br /> (the same goes for other tags)

camelCase is the new standard

In HTML you’ll find attributes without any case (e.g. onchange). In JSX, they are renamed to their camelCase equivalent:

onchange=>onChangeonclick=>onClickonsubmit=>onSubmit

class becomes className

Due to the fact that JSX is JavaScript, and class is a reserved word, you can't write

<p class="description">but you need to use

<p className="description">The same applies to for which is translated to htmlFor.

CSS in React

JSX provides a cool way to define CSS.

If you have a little experience with HTML inline styles, at first glance you’ll find yourself pushed back 10 or 15 years, to a world where inline CSS was completely normal (nowadays it’s demonized and usually just a “quick fix” go-to solution).

JSX style is not the same thing: first of all, instead of accepting a string containing CSS properties, the JSX style attribute only accepts an object. This means you define properties in an object:

var divStyle = {

color: 'white'

}

ReactDOM.render(<div style={divStyle}>Hello World!</div>, mountNode)or

ReactDOM.render(<div style={{ color: 'white' }}>Hello World!</div>, mountNode)The CSS values you write in JSX are slightly different from plain CSS:

- the keys property names are camelCased

- values are just strings

- you separate each tuple with a comma

Why is this preferred over plain CSS / SASS / LESS?

CSS is an unsolved problem. Since its inception, dozens of tools around it rose and then fell. The main problem with JS is that there is no scoping and it’s easy to write CSS that is not enforced in any way, thus a “quick fix” can impact elements that should not be touched.

JSX allows components (defined in React for example) to completely encapsulate their style.

Is this the go-to solution?

Inline styles in JSX are good until you need to

- write media queries

- style animations

- reference pseudo classes (e.g.

:hover) - reference pseudo elements (e.g.

::first-letter)

In short, they cover the basics, but it’s not the final solution.

Forms in JSX

JSX adds some changes to how HTML forms work, with the goal of making things easier for the developer.

value and defaultValue

The value attribute always holds the current value of the field.

The defaultValue attribute holds the default value that was set when the field was created.

This helps solve some weird behavior of regular DOM interaction when inspecting input.value and input.getAttribute('value') returning one the current value and one the original default value.

This also applies to the textarea field, e.g.

<textarea>Some text</textarea>but instead

<textarea defaultValue={'Some text'} />For select fields, instead of using

<select>

<option value="x" selected>

...

</option>

</select>use

<select defaultValue="x">

<option value="x">...</option>

</select>A more consistent onChange

Passing a function to the onChange attribute you can subscribe to events on form fields.

It works consistently across fields, even radio, select and checkbox input fields fire a onChange event.

onChange also fires when typing a character into an input or textarea field.

JSX auto escapes

To mitigate the ever present risk of XSS exploits, JSX forces automatic escaping in expressions.

This means that you might run into issues when using an HTML entity in a string expression.

You expect the following to print © 2017:

<p>{'© 2017'}</p>But it’s not, it’s printing © 2017 because the string is escaped.

To fix this you can either move the entities outside the expression:

<p>© 2017</p>or by using a constant that prints the Unicode representation corresponding to the HTML entity you need to print:

<p>{'\u00A9 2017'}</p>White space in JSX

To add white space in JSX there are 2 rules:

Rule 1: Horizontal white space is trimmed to 1

If you have white space between elements in the same line, it’s all trimmed to 1 white space.

<p>Something becomes this</p>becomes

<p>Something becomes this</p>Rule 2: Vertical white space is eliminated

<p>

Something

becomes

this

</p>becomes

<p>Somethingbecomesthis</p>To fix this problem you need to explicitly add white space, by adding a space expression like this:

<p>

Something

{' '}becomes

{' '}this

</p>or by embedding the string in a space expression:

<p>

Something

{' becomes '}

this

</p>Adding comments in JSX

You can add comments to JSX by using the normal JavaScript comments inside an expression:

<p>

{/* a comment */}

{

//another comment

}

</p>Spread attributes

In JSX a common operation is assigning values to attributes.

Instead of doing it manually, e.g.

<div>

<BlogPost title={data.title} date={data.date} />

</div>you can pass

<div>

<BlogPost {...data} />

</div>and the properties of the data object will be used as attributes automatically, thanks to the ES6 spread operator.

How to loop in JSX

If you have a set of elements you need to loop upon to generate a JSX partial, you can create a loop, and then add JSX to an array:

const elements = [] //..some array

const items = []

for (const [index, value] of elements.entries()) {

items.push(<Element key={index} />)

}Now when rendering the JSX you can embed the items array simply by wrapping it in curly braces:

const elements = ['one', 'two', 'three'];

const items = []

for (const [index, value] of elements.entries()) {

items.push(<li key={index}>{value}</li>)

}

return (

<div>

{items}

</div>

)You can do the same directly in the JSX, using map instead of a for-of loop:

const elements = ['one', 'two', 'three'];

return (

<ul>

{elements.map((value, index) => {

return <li key={index}>{value}</li>

})}

</ul>

)Components

A component is one isolated piece of interface. For example in a typical blog homepage you might find the Sidebar component, and the Blog Posts List component. They are in turn composed of components themselves, so you could have a list of Blog post components, each for every blog post, and each with its own peculiar properties.

React makes it very simple: everything is a component.

Even plain HTML tags are component on their own, and they are added by default.

The next 2 lines are equivalent, they do the same thing. One with JSX, one without, by injecting <h1>Hello World!</h1> into an element with id app.

import React from 'react'

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom'

ReactDOM.render(<h1>Hello World!</h1>, document.getElementById('app'))

ReactDOM.render(

React.DOM.h1(null, 'Hello World!'),

document.getElementById('app')

)See, React.DOM exposed us an h1 component. Which other HTML tags are available? All of them! You can inspect what React.DOM offers by typing it in the Browser Console:

(the list is longer)

The built-in components are nice, but you’ll quickly outgrow them. What React excels in is letting us compose a UI by composing custom components.

Custom components

There are 2 ways to define a component in React.

A function component:

const BlogPostExcerpt = () => {

return (

<div>

<h1>Title</h1>

<p>Description</p>

</div>

)

}A class component:

import React, { Component } from 'react'

class BlogPostExcerpt extends Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Title</h1>

<p>Description</p>

</div>

)

}

}Up until recently, class components were the only way to define a component that had its own state, and could access the lifecycle methods so you could do things when the component was first rendered, updated or removed.

React Hooks changed this, so our function components are now much more powerful than ever and I believe we’ll see fewer and fewer class components in the future, although it will still be perfectly valid way to create components.

There is also a third syntax which uses the ES5 syntax, without the classes:

import React from 'react'

React.createClass({

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Title</h1>

<p>Description</p>

</div>

)

}

})You’ll rarely see this in modern, > ES6 codebases.

State

Setting the default state of a component

In the Component constructor, initialize this.state. For example the BlogPostExcerpt component might have a clicked state:

class BlogPostExcerpt extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = { clicked: false }

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Title</h1>

<p>Description</p>

</div>

)

}

}Accessing the state

The clicked state can be accessed by referencing this.state.clicked:

class BlogPostExcerpt extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = { clicked: false }

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Title</h1>

<p>Description</p>

<p>Clicked: {this.state.clicked}</p>

</div>

)

}

}Mutating the state

A state should never be mutated by using

this.state.clicked = trueInstead, you should always use setState() instead, passing it an object:

this.setState({ clicked: true })The object can contain a subset, or a superset, of the state. Only the properties you pass will be mutated, the ones omitted will be left in their current state.

Why you should always use setState()

The reason is that using this method, React knows that the state has changed. It will then start the series of events that will lead to the Component being re-rendered, along with any DOM update.

Unidirectional Data Flow

A state is always owned by one Component. Any data that’s affected by this state can only affect Components below it: its children.

Changing the state on a Component will never affect its parent, or its siblings, or any other Component in the application: just its children.

This is the reason the state is often moved up in the Component tree.

Moving the State Up in the Tree

Because of the Unidirectional Data Flow rule, if two components need to share state, the state needs to be moved up to a common ancestor.

Many times the closest ancestor is the best place to manage the state, but it’s not a mandatory rule.

The state is passed down to the components that need that value via props:

class Converter extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = { currency: '€' }

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<Display currency={this.state.currency} />

<CurrencySwitcher currency={this.state.currency} />

</div>

)

}

}The state can be mutated by a child component by passing a mutating function down as a prop:

class Converter extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = { currency: '€' }

}

handleChangeCurrency = event => {

this.setState({ currency: this.state.currency === '€' ? '$' : '€' })

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<Display currency={this.state.currency} />

<CurrencySwitcher

currency={this.state.currency}

handleChangeCurrency={this.handleChangeCurrency}

/>

</div>

)

}

}

const CurrencySwitcher = props => {

return (

<button onClick={props.handleChangeCurrency}>

Current currency is {props.currency}. Change it!

</button>

)

}

const Display = props => {

return <p>Current currency is {props.currency}.</p>

}Props

Props is how Components get their properties. Starting from the top component, every child component gets its props from the parent. In a function component, props is all it gets passed, and they are available by adding props as the function argument:

const BlogPostExcerpt = props => {

return (

<div>

<h1>{props.title}</h1>

<p>{props.description}</p>

</div>

)

}In a class component, props are passed by default. There is no need to add anything special, and they are accessible as this.props in a Component instance.

import React, { Component } from 'react'

class BlogPostExcerpt extends Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1>{this.props.title}</h1>