During my 18 year career as a programmer, I’ve worked on dozens of different projects, from robotics to finance to healthcare and telecom. And I’ve had the opportunity to work with hundreds of programmers from all sorts of backgrounds — each with their own habits and attitudes.

I’ve learned that no matter where they come from or what they do, all programmers fall somewhere on this spectrum:

The academic

At one end of the spectrum are are programmers who are great with theory. They love learning, reading, exploring and innovating. For them, every line of code feels like a contribution to the world, a heritage for the future even. If there’s a flaw in the code, it’s because they don’t know any better yet.

In their world, the code should be perfect, bug-free and according to the best practices. They appreciate smart ways of doing things, and love to keep up to date with the latest technologies.

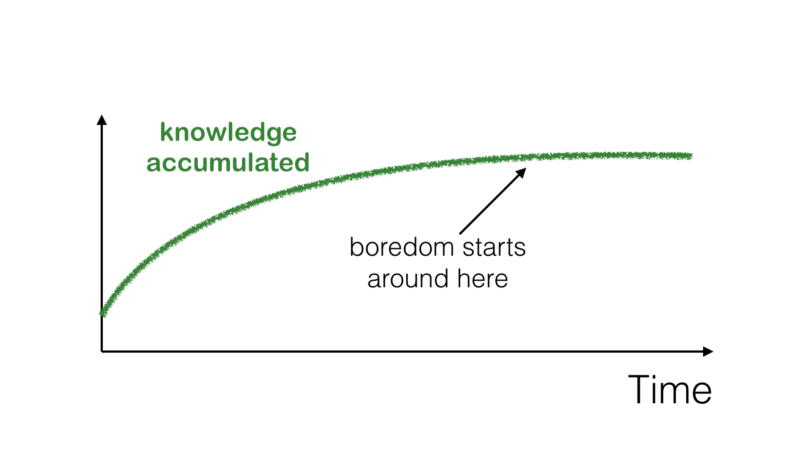

Unfortunately, the academic will get bored when the learning stops, and will look for other projects — or even change jobs:

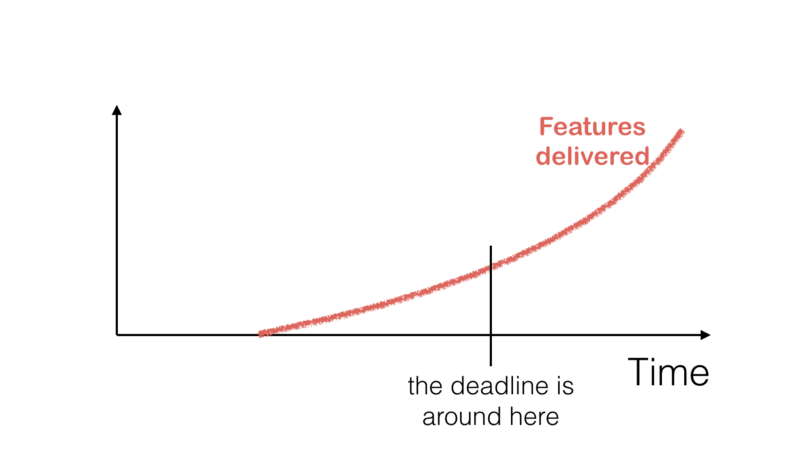

The downside of this way of working is that projects progress slowly. When you learn something, you tend to also stumble upon something else you’d like to learn. And this cycle of going down rabbit holes can go on for quite a while before any significant features are delivered:

But this isn’t all bad. When the product needs to stand up to high standards, the academic is actually the right type of programmer.

For example, for healthcare software, patient safety is super important. You want your programmers to take their time and learn their stuff before pushing code into the “production environment” that is people’s lives.

Even a small bug can be fatal.

Another example is the financial sector, where a simple mistake can cost a lot. This is also true of most security or safety-demanding software — where the reputation of the business is often at stake.

The hacker

At the other extreme of the spectrum is the hacker, who is the ideal “knowledge worker” according to the Deep Work from Cal Newport. Hackers learn fast and (ideally) deliver results at a constant pace. They rarely say “no” to a feature request, and will shove it in the code somehow.

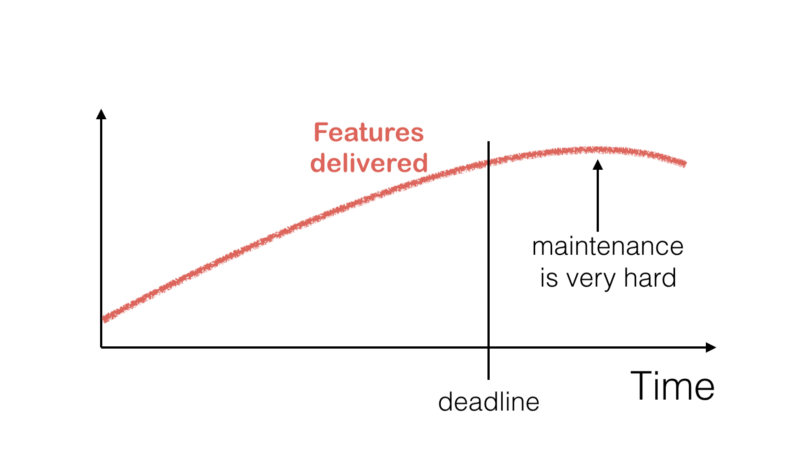

But after a while, the code becomes patchy. The process gets clogged to an extent that adding new features can break other code that should otherwise be working:

Technical debt piles up, and it hurts the business in the long run.

These programmers make the perfect candidates for consultant jobs, where the project is hit and run. They may even get paid to fix the flaws they have put into the code in the first place! Good for the consultancy firm, bad for your business. Unless of course you happen to be in the prototyping or proof of concept phase of product development, and much of the code is likely to be rewritten.

The hacker is ideal for startups that are in the early Minimum Viable Product development stage. The hacker can quickly generate results. They bring the best bang-for-buck (in terms of both money and time). In these situations, the academic would paralyze development.

Conclusion

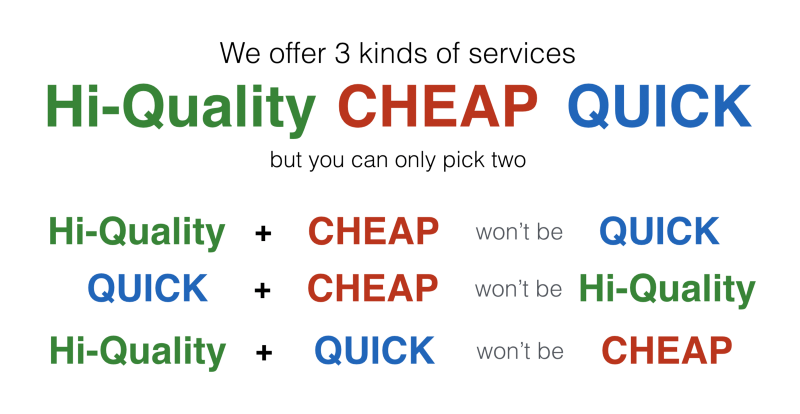

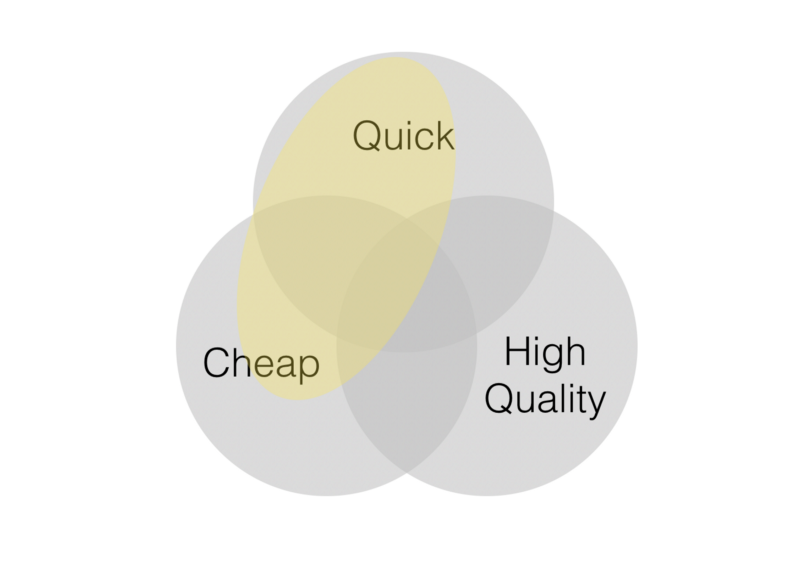

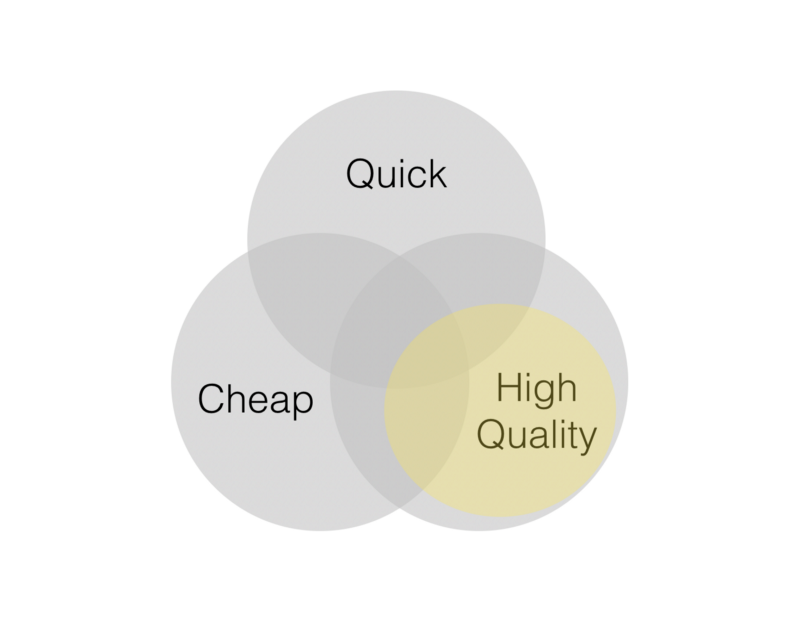

There’s a joke that goes like this:

But in reality there are two types of doers:

The hacker can do the job quickly and cheaply, with little focus on the quality. This won’t be cheap in the long run, considering all the maintenance costs.

The academic focuses on quality, but things will move very slowly, and it certainly costs more until you get some tangible results. Also when they get bored, they may impose even more cost on the project by leaving — or worse by staying and not feeling passionate about their job.

The hacker and the academic are two extreme ends of the spectrum, and in reality most programmers fall somewhere in between. It’s important to pick the right developers for your project and the specific type of software you’re building.

Ideally you can start a project with the hacker, while the academic can ride along in the back seat, sharpening their swords for when the product becomes a hit and needs heavy refactoring.

Also people are not made in factories. They can change. Some of the smartest developers I’ve met can shift between being the hacker and being the academic depending on the project stage. This is a golden skill which many developers cultivate through years of experience.

If you ❤ what you read, please share it and follow me to stay up to date with the latest essays. Also, check out my other two popular essays:

Disclaimer: all opinions are mine, I don’t represent any company or business.

Update: after sharing this article I got a couple of good comments that worth sharing:

The “academic” will learn stuff once [but] apply it many times. The “hacker” will never learn. So the graph for “features delivered” are only applicable when faced with a platform/stack/framework. The second time around, the “academic” will leave the “hacker” in the dust.

I agree a lot with your separation between academics being more focused on “correctness” and hackers focusing on “getting things done”. I belong closer to the latter group and have had an extremely well working collaboration with a colleague who is more towards the academic side. Me alone can get a lot of shit done, but that does not mean it is nice code. He on the other hand can still get a lot done, but will actually spend the time on making it good as well. I also see a difference in how problems are approached, he would read up on related solutions before designing the solution, where I would instead of reading up, experiment with different solutions. My way gives quicker results, while his results in better solutions. The combination of these things make for a very productive and interesting workday