Hey everyone! In this article, I'm going to show you what's new in the latest of version of React – React 18 alpha – in under 8 minutes.

First, you might be wondering whether the latest set of changes will break anything with your current setup, or whether you will have to learn new completely unrelated concepts.

Well, don't worry – you can continue with your present work or continue learning your current React course as it is, as React 18 doesn't break anything.

If you want to watch a video to supplement your reading, check it out here:

For those of you who really want to learn what's happening, here's the breakdown.

Just a quick note: React 18 is still in alpha and isn't out yet. So this is what you can expect when it's released.

What is Concurrency in React?

The major theme for this release is concurrency. To start with, let's look at what concurrency is.

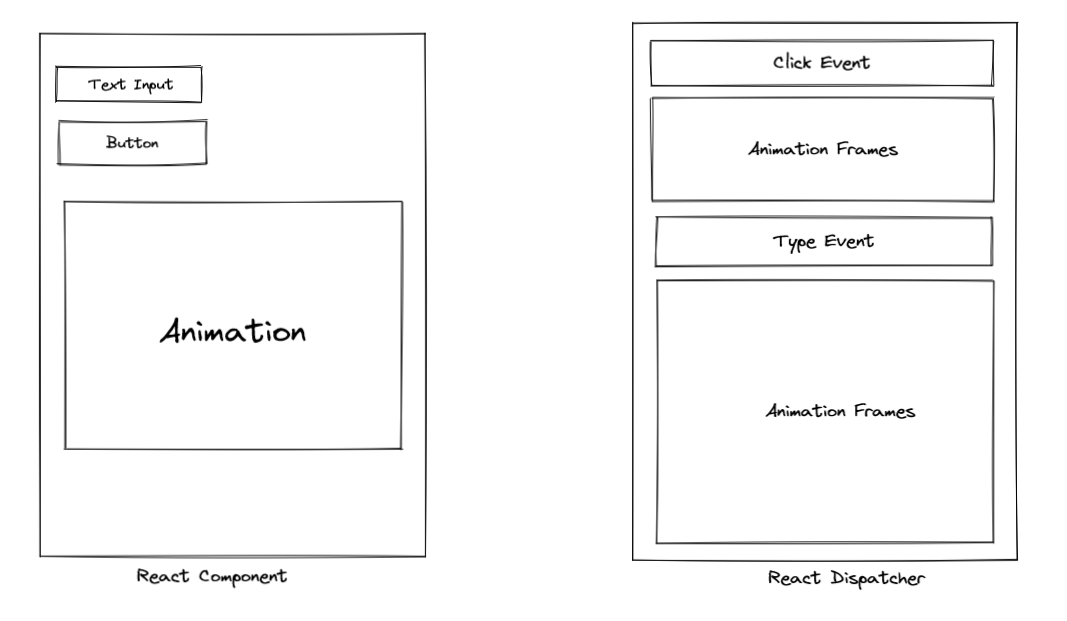

Concurrency is the ability to execute multiple tasks simultaneously. Taking the example of a standard React app, let's consider that an animation is playing in a component, and at the same time a user is able to click or type in other React components.

Here, while the user is typing and clicking on buttons, an animation is also rendering there within the context of React.

React has to manage all the function calls, hook calls, and event callbacks, several of which can even occur at the same time. If React spends all its time rendering animation frames, the user will feel like the app is "stuck", since it won't react to their inputs.

Now React, running on a single threaded process, has to combine, reorder and prioritize these events and functions so that it can give users an optimum and performant experience.

To do this, React uses a "dispatcher" internally which is responsible for prioritizing and invoking these callbacks.

Before React 18, the user had no way to control the invocation order of these functions. But now, React is giving some control of this event loop to the user via the Transition API.

You can read more about this in this article by Dan Abramov: An ELI5 of concurrency.

The Transition API

The developers of React have exposed a few APIs which allow React users to have some control over concurrency.

One of these APIs is startTransition, which allows developers to indicate to React which actions may block the thread and cause lag on screen.

Typically, these actions are the ones you might have previously used debounce for, like network calls via a search API, or render-heavy processes like searching through an array of 1000 strings.

Updates wrapped in startTransition are marked as non-urgent and are interrupted if more urgent updates like clicks or key presses come in.

If a transition gets interrupted by the user (for example, by typing multiple letters into a search field), React will throw out the stale rendering work that wasn’t finished and render only the latest update.

Transition API example

To understand this in more detail, let's consider a component with a search field. Let's say it has 2 functions to control the state:

// Update input value

setInputValue(input)

// Update the searched value and search results

setSearchQuery(input);

setInputValue is responsible for updating the input field, while setSearchQuery is responsible for performing search based on the present input value. Now, if these function calls happened synchronously every time the user started typing, either of 2 things would happen:

- Several search calls would be made, which would delay or slow down other network calls.

- Or, more likely, the search operation would turn out to be very heavy and would lock up the screen on each keystroke.

One way to solve this problem would've been using debounce, which would space out the network calls or search operations. But, the problem with debounce is that we have to play with and optimize the debounce timer quite frequently.

So in this case, we can wrap setSearchQuery in startTransition, allowing it to handle it as non-urgent and to be delayed as long as the user is typing.

import { startTransition } from 'react';

// Urgent: Show what was typed

setInputValue(input);

// Mark any state updates inside as transitions

startTransition(() => {

// Transition: Show the results

setSearchQuery(input);

});

Transitions let you keep most interactions snappy even if they lead to significant UI changes. They also let you avoid wasting time rendering content that's no longer relevant.

React also provides a new hook called useTransition , so you can show a loader while the transition is pending. This helps in indicating to the user that the app is processing their input and will display the results shortly.

import { useTransition } from'react';

const [isPending, startTransition] = useTransition();

const callback = () => {

// Urgent: Show what was typed

setInputValue(input);

// Mark any state updates inside as transitions

startTransition(() => {

// Transition: Show the results

setSearchQuery(input);

});

}

{isPending && <Spinner />}

As a rule of thumb, you can use the transition API wherever network calls or render-blocking processes are present.

You can read more about the API in this article, An explanation of startTransition by Ricky from the Core React team.

Demos of the Transition API

Use useTransition and Suspense in an app: https://codesandbox.io/s/sad-banach-tcnim?file=/src/App.js:664-676

Demo of startTransition with a complex rendering algorithm: https://react-fractals-git-react-18-swizec.vercel.app/

Batching in React

Next up is batching. Batching is something that the developer generally doesn't have to care about, but it's good to know what's happening behind the scenes.

Whenever you are using setState to change a variable inside any function, instead of making a render at each setState, React instead collects all setStates and then executes them together. This is known as batching.

function App() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

const [flag, setFlag] = useState(false);

function handleClick() {

setCount(c => c + 1); // Does not re-render yet

setFlag(f => !f); // Does not re-render yet

// React will only re-render once at the end (that's batching!)

}

return (

<div>

<button onClick={handleClick}>Next</button>

<h1 style={{ color: flag ? "blue" : "black" }}>{count}</h1>

</div>

);

}

This is great for performance because it avoids unnecessary re-renders. It also prevents your component from rendering “half-finished” states where only one state variable was updated, which may cause UI glitches and bugs within your code.

However, React didn't used to be consistent about when it performed batching. This was because React used to only batch updates during browser events (like a click), but here we’re updating the state after the event has already been handled (in a fetch callback):

function App() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

const [flag, setFlag] = useState(false);

function handleClick() {

fetchSomething().then(() => {

// React 17 and earlier does NOT batch these because

// they run *after* the event in a callback, not *during* it

setCount(c => c + 1); // Causes a re-render

setFlag(f => !f); // Causes a re-render

});

}

return (

<div>

<button onClick={handleClick}>Next</button>

<h1 style={{ color: flag ? "blue" : "black" }}>{count}</h1>

</div>

);

}

Starting in React 18 with [createRoot](<https://github.com/reactwg/react-18/discussions/5>), all state updates will be automatically batched, no matter where they originate from.

This means that updates inside of timeouts, promises, native event handlers or any other event will batch the same way as updates inside of React events. This will result in less rendering work by React, and therefore better performance in applications.

You can read more about batching here in An explanation of Batching by Dan Abramov.

Demos of batching

Before React 18: https://codesandbox.io/s/hopeful-fire-ge4t2?file=/src/App.tsx

After React 18: https://codesandbox.io/s/morning-sun-lgz88?file=/src/index.js

The Suspense API

React 18 includes a lot of changes to improve React performance in a Server-Side Rendered context. Server-side rendering is a way of rendering the JS data to HTML on the server to save computation on the frontend. This results in a faster initial page load in most cases.

React performs Server Side Rendering in 4 sequential steps:

- On the server, data is fetched for each component.

- On the server, the entire app is rendered to HTML and sent to the client.

- On the client, the JavaScript code for the entire app is fetched.

- On the client, the JavaScript connects React to the server-generated HTML, which is known as Hydration.

React 18 introduces the Suspense API, which allows you to break down your app into smaller independent units, which will go through these steps independently and won’t block the rest of the app. As a result, your app’s users will see the content sooner and be able to start interacting with it much faster.

How does the Suspense API work?

Streaming HTML

With today’s SSR, rendering HTML and hydration are “all or nothing”. The client has to fetch and hydrate all of the app at once.

But React 18 gives you a new possibility. You can wrap a part of the page with <Suspense>.

<Suspense fallback={<Spinner />}>

{children}

</Suspense>

By wrapping the component in <Suspense>, we tell React that it doesn’t need to wait for comments to start streaming the HTML for the rest of the page. Instead, React will send the placeholder (a spinner) instead.

When the data for the comments is ready on the server, React will send additional HTML into the same stream, as well as a minimal inline <script> tag to put that HTML in the “right place”.

Selective Hydration

Before React 18, hydration couldn't start if the complete JavaScript code for the app hadn't loaded in. For larger apps, this process can take a while.

But in React 18, <Suspense> lets you hydrate the app before the child components have loaded in.

By wrapping components in <Suspense>, you can tell React that they shouldn’t block the rest of the page from streaming—and even hydration. This means that you no longer have to wait for all the code to load in order to start hydrating. React can hydrate parts as they’re being loaded.

These 2 features of Suspense and several other changes introduced in React 18 speed up initial page loads tremendously.

You can read more in this article An explanation of Suspense SSR and related changes by Dan Abramov

Demo of Suspense

https://codesandbox.io/s/recursing-mclaren-1ireo?file=/src/index.js:458-466

Summary

So to summarize, the features that React 18 brings are:

- Concurrency control with the Transition API,

- Automatic Batching of function calls and events to improve in-app performance, and

- Much faster page loads for SSR with Suspense.

Although not a very large departure from the previous version of React, all of these changes are making React a trend-setter for all the frameworks out there.

Thanks for reading this! You can check out my previous posts and tutorials on React here on freeCodeCamp. You can also follow me on Twitter @thewritingdev, where I post daily content on React and web development.