Very few programming languages are as universally loved as Python. The brainchild of Dutch programmer Guido van Rossum, Python is easy to learn, powerful, and an utter joy to work with.

Thanks to its popularity, video and written resources about Python are plentiful. This handbook, however, tries to be a bit different by not being a definitive guide to the language.

Instead you'll learn about all the topics that I consider to be the language fundamentals with a lot of code examples.

I haven't discussed object-oriented programming in this handbook because I believe it to be a very broad subject deserving of its own separate handbook.

Near the end, I've also listed out some learning resources to further your knowledge of Python and programming in general.

Without any further ado, let's jump in!

Table of Contents

- Prerequisites

- How to Setup Python on Your Computer

- How to Install a Python IDE on Your Computer

- How to Create a New Project on PyCharm

- How to Write the Hello World Program in Python

- How to Initialize and Publish a Git Repository From PyCharm

- How to Work With Variables and Different Types of Data in Python

- How to Work With Simple Numbers in Python

- How to Take Inputs From Users in Python

- How to Work With Strings in Python

- What Are the Sequence Types in Python?

- What Are the Iterable Types and How to Use them for Loops in Python

- How to Use While Loops in Python

- How to Write Nested Loops in Python

- What Are Some Common Sequence Type Operations in Python?

- What Are Some String Type Operations in Python?

- How to Write Conditional Statements in Python

- What are Relational and Logical Operators in Python?

- What Are Assignment Operators in Python?

- What Is the Set Type in Python?

- What Is the Mapping Type in Python?

- How to Write Functions in Python

- What Are Modules in Python?

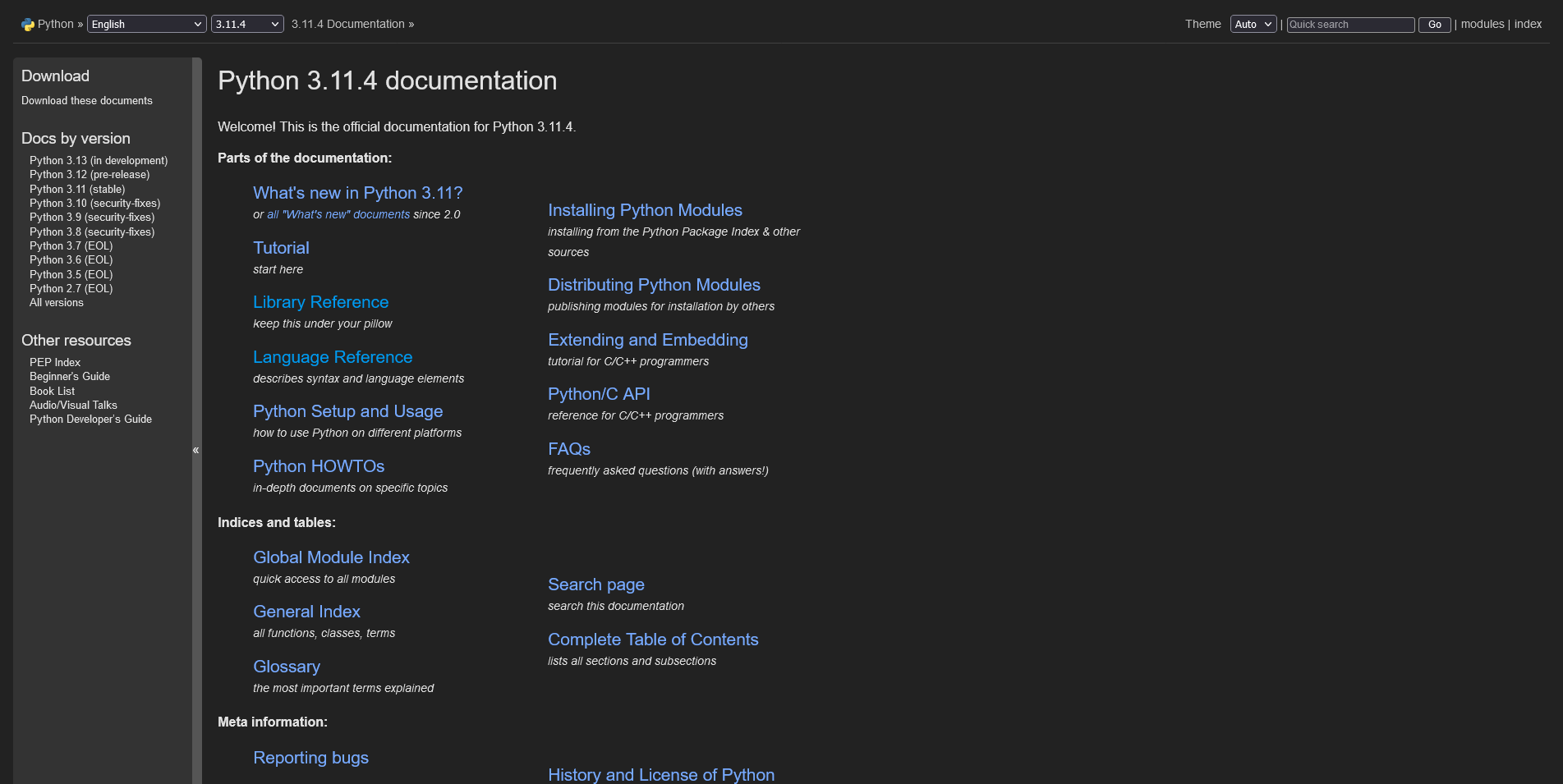

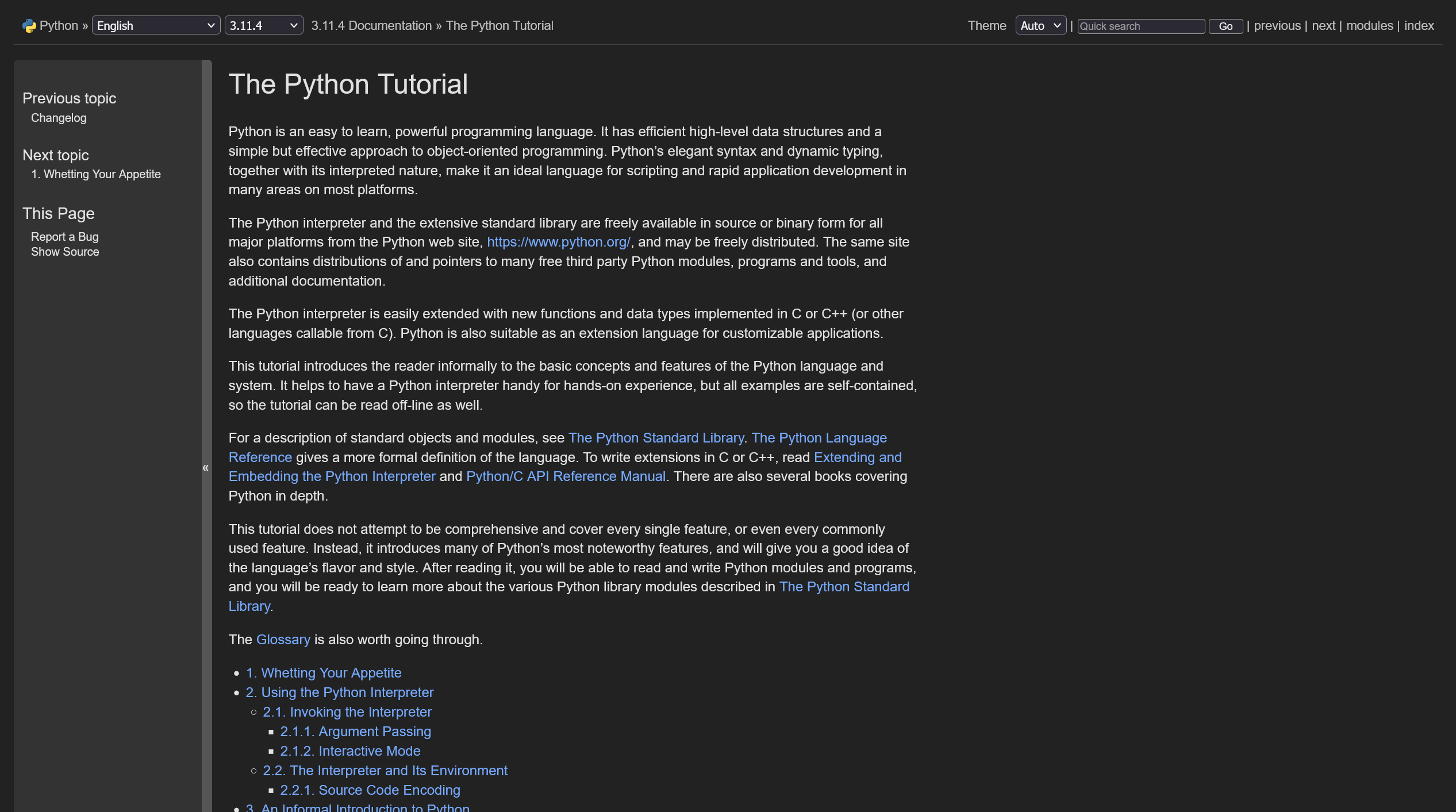

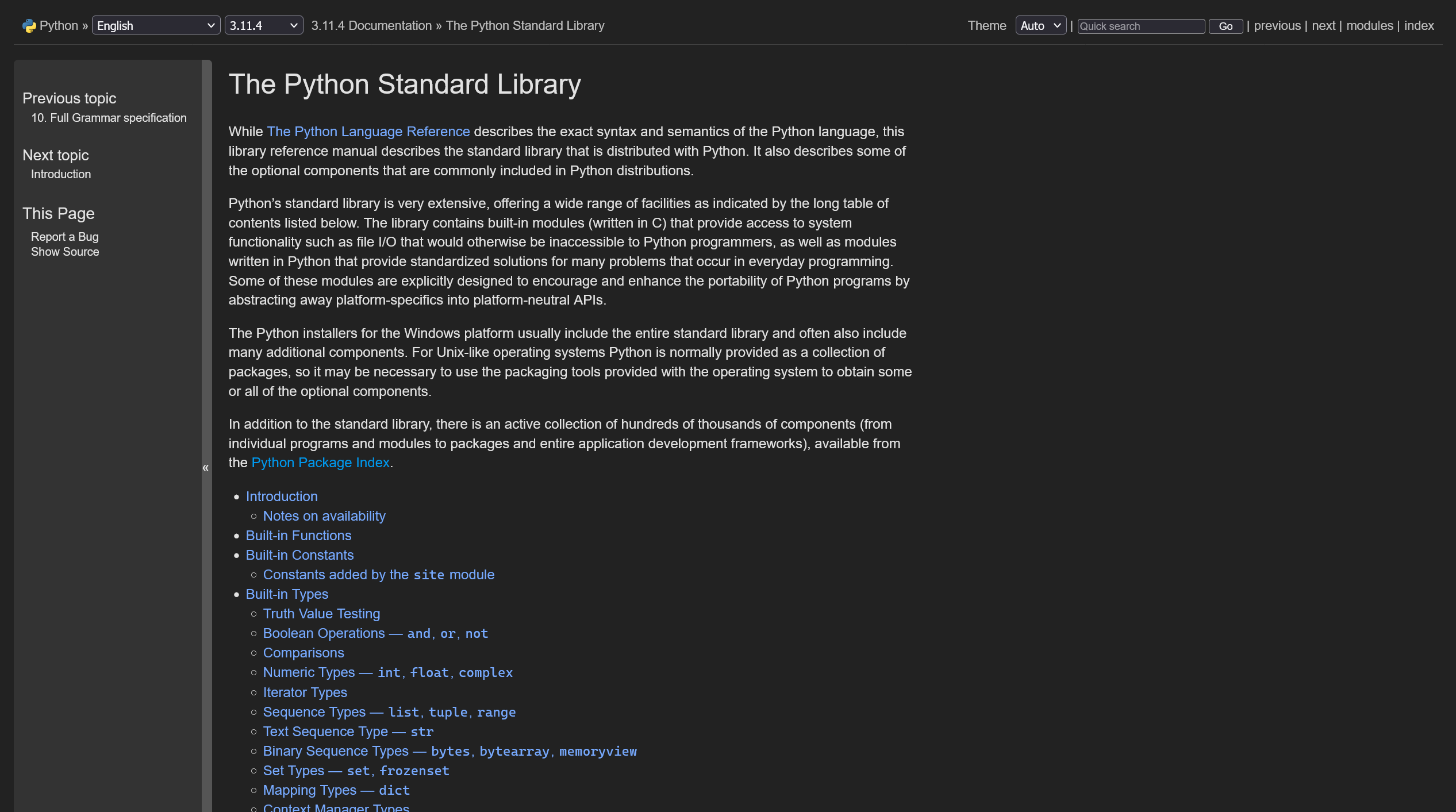

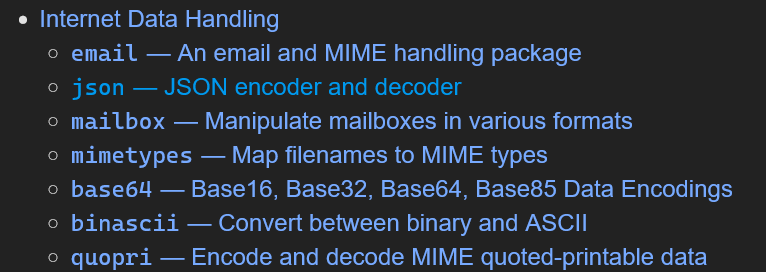

- How to Use the Python Documentation Efficiently

- What's Next?

- Conclusion

Prerequisites

You don't need to know any other programming language for this book, but knowing one may help you understand the basics of Python.

Other than that you'll need to be efficient enough with your choice of operating system to download and install new software, and gain administrative access if needed.

How to Setup Python on Your Computer

Installing Python on your computer is a very straightforward process. In fact, if you're on a Linux system, Python should already be installed.

Open up your terminal window and execute the following command:

python --versionIf Python is installed on your system, you'll get an output like Python 3.10.4 or some other minor version.

Although most of the modern Linux distribution use Python 3 as default, some of the older distributions may still use Python 2 by default.

So if the aforementioned command refers to Python 2, try out the following command:

python3 --versionI'd also suggest that you check for updates on your Linux distribution and install any new updates for Python.

Although Python comes preinstalled with macOS as well, I'd suggest that you follow this article by Dillion Megida and install a more recent version.

Finally, for Windows, I'd suggest you follow an article by Md. Fahim Bin Amin and properly install the latest version of Python.

As long as you have a Python 3 version installed, you're good to go.

How to Install a Python IDE on Your Computer

Much of your experience as a developer will depend on what program you've chosen to write your code in. A good integrated development environment (IDE) or Code Editor can really boost your productivity.

These days Visual Studio Code has become the go to code editor for all languages and platforms. But for the sake of simplicity, we'll use PyCharm in this book.

If you'd like to use VS Code, have written a full-length article on how to configure Visual Studio Code for Python development. Feel free to check that out if you do not mind configuring your editor manually.

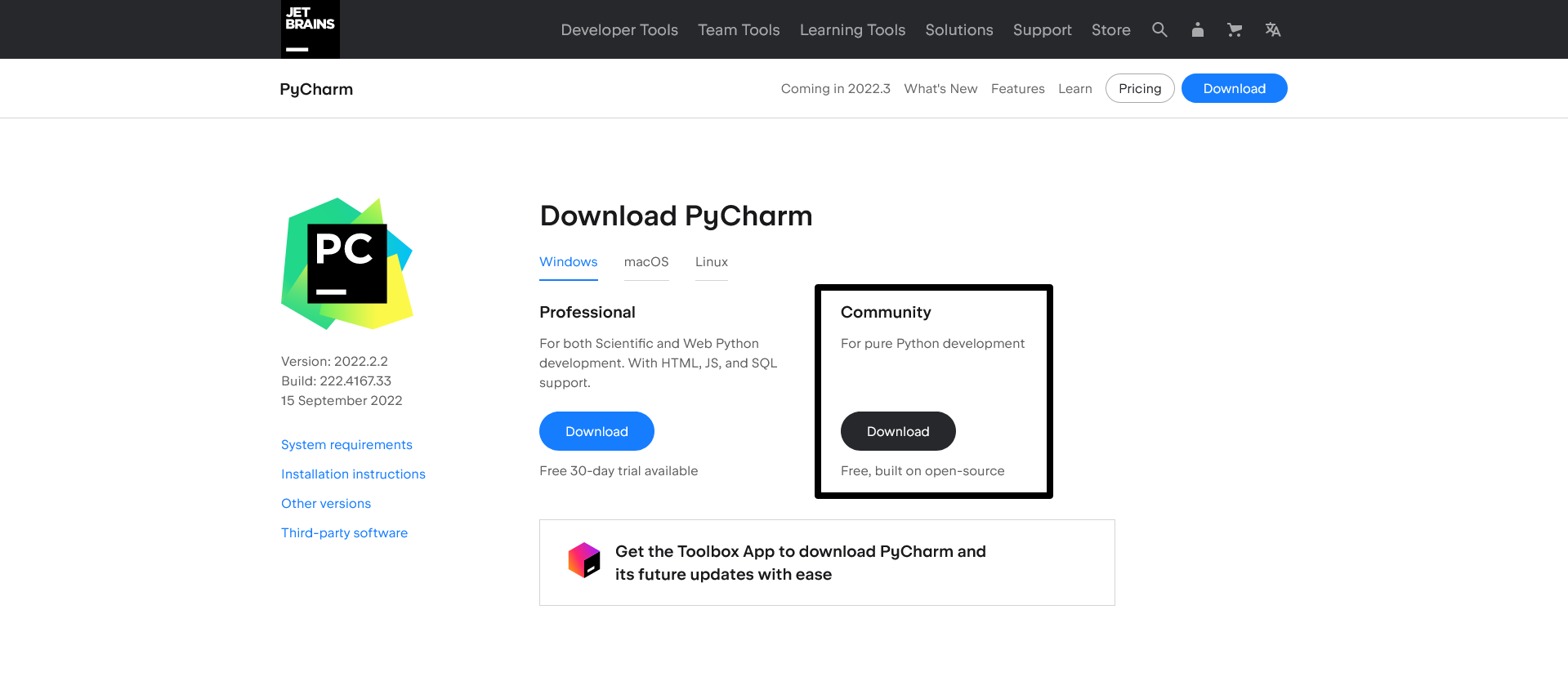

The professional edition of the IDE can cost you $89.00 per year but there is also a free and open-source community edition. Head over to the PyCharm download page.

Use the black "Download" button to download the community edition. The file size should be a little larger than 350 megabytes.

On Windows you'll get an executable installer, on macOS you'll get an Apple disc image, and on Linux you'll get a TAR archive.

I won't demonstrate the installation process in this book since it's similar to installing any other software on your machine.

Once installed, you can start the IDE from your start menu/app launcher. On your first launch, you'll be given the chance to configure a few things. I'd suggest you keep the defaults.

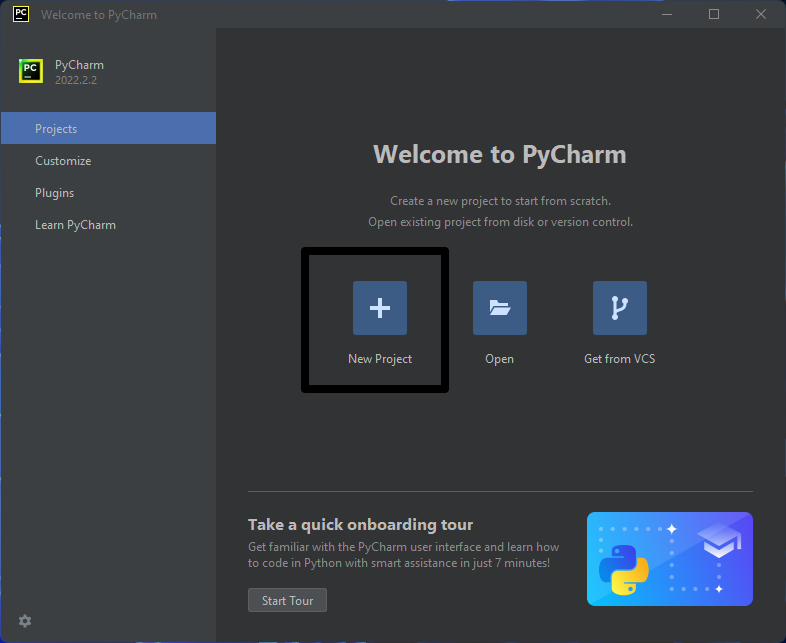

Once the configuration wizard ends, you should see the following welcome window:

Picking one IDE or code editor instead of the other one will not affect your experience with following this handbook, so feel free to use whatever you feel comfortable with.

How to Create a New Project on PyCharm

If you have the welcome window open from the previous section, click on the "New Project" button.

In the next step, pick a location to store your project:

In the location input box, the HelloWorld part is the name of the project. Then make sure you have "New environment using Virtualenv" selected. Then, make sure that the correct version of Python is selected from the "Base interpreter" dropdown.

Virtualenv is a program that can create isolated Python environments from a given base interpreter. This is very helpful because later on when you'll work on multiple Python projects, their dependencies may conflict with each other.

Creating isolated environments for each project will solve that issue and it'll also keep your global Python installation free from any unnecessary package installation.

Since this may be your first Python project, I'd suggest you leave the "Create a main.py welcome script" option checked. Once you're happy with your choices, click the "Create" button.

The project creation process shouldn't take very long. Once it's done, the IDE should open the project automatically for you.

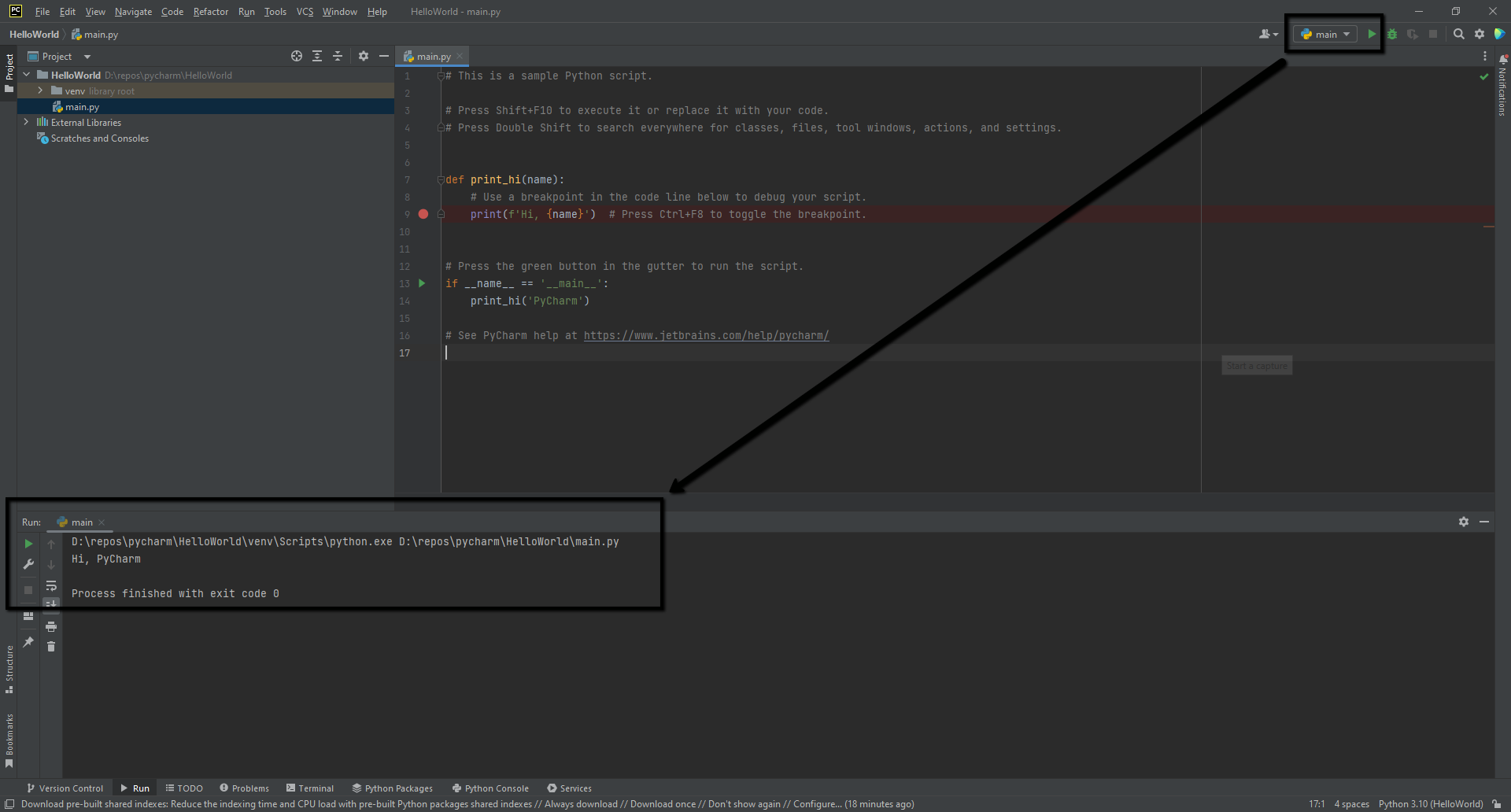

You can use the play button at the top right corner to run the code. The button is configured to run the "main.py" file by default.

That's why you can see "main" written by its side. You can write your custom configuration as well, but that's a topic for a later section.

You can see the output of your program at the bottom of the IDE. PyCharm comes with support for TODO comments, a built in terminal and more. You'll learn about a bunch of these features as you go forward.

How to Write the Hello World Program in Python

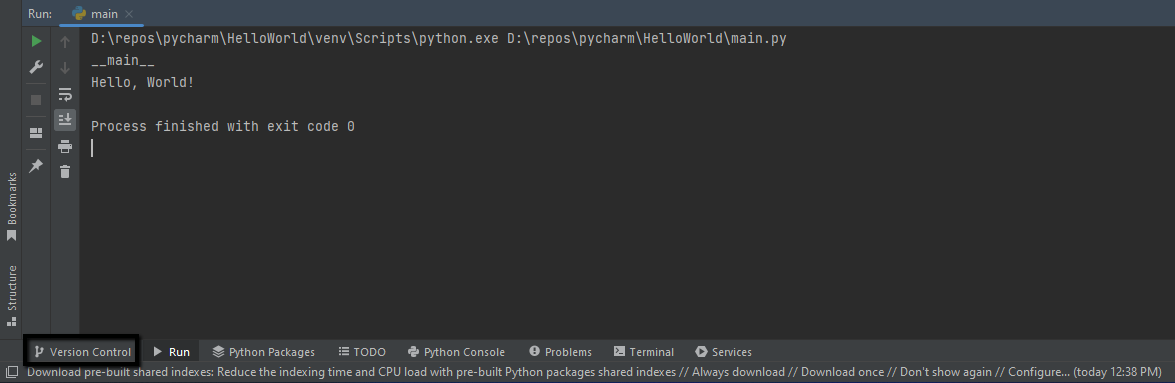

Continuing on from the last section, open up the "main.py" file and replace all the preexisting code with the following line of code:

print('Hello, World!')

# Hello, World!The print() function prints out anything that you pass into the set of parenthesis. You don't have to name your Python file "main.py" specifically. It's just a way to let you know that this is the entry point to this program.

That's all you need to write the simplest executable program in Python. But there is even a better way to do it. Update the code as follows:

def main():

print('Hello, World!')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Hello, World!As you keep working on bigger projects, you'll eventually have more than one Python file in your project and this way of writing a script can be useful.

To simulate a bigger project, create another Python file by right clicking on the "HelloWorld" project name and selecting "Python File" under the "New" sub menu.

Name your file something like "library" and press enter while "Python file" is highlighted in the list of file types.

A new file with the name "library.py" will show up on your project folder. Put the following line of code inside the file:

def greet():

print('Hello, World!')

This is a very simple function that prints out "Hello, World!" on the console. You can import and use this function in your "main.py" file.

To do so, update the code for "main.py" file as follows:

from library import greet

def main():

greet()

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Hello, World!You're importing the greet() function from the "library.py" file and executing that inside the main() function.

Right now in your project, you have two types of Python file. You have the "main.py" file which is a script. In other words, you can run this file.

Then you have the "library.py" file which is a library. In other words, it houses a number of useful functions and variables that you can import inside other Python files.

Now imagine you have hundreds of files in your project and they more or less look the same. How would someone else find the entry point to the program?

The easiest way would be to perform a search for the line if __name__ == '__main__' on the entire project. This makes your code a lot more readable.

Now that I have you convinced that this is the way to go, let me explain what is actually going on here.

The __name__ is a special Python variable. In case of a script, the value of this variable will be __main__ and in case of a library, its value will be the name of that file.

So in the aforementioned program, the value of __name__ inside the "main.py" file will be __main__ and library inside the "library.py" file.

If you change the name of then "main.py" file to something else, the value will still be __main__ because it's a script.

Nothing is stopping the "library.py" file from being a script, though. If you run that file instead, it'll become a script.

In languages like C/C++/Go/Java, you'll have a specified main function. That function will be the entry point to the program.

Since Python doesn't have anything like that, the usage of the if __name__ == '__main__' expression enforces a sense of a specified entry point to your program.

It tells the programmer and the IDE that this script is for execution (not for importing inside other Python files).

How to Initialize and Publish a Git Repository From PyCharm

You may already be familiar with Git and know how to initialize a new repository. If you prefer using some other Git client, that's totally fine.

However I think knowing how to make commits right from your IDE can boost your productivity.

Keep in mind you'll need to have Git installed and configured on your system. If you don't have that, this article by Bolaji Ayodeji may come in handy.

Now, continuing on from the last section, if you look at the bottom of your IDE, you should see a "Version Control" tab.

Click on it and you should switch to the version control tab. Now click on the "Create Git repository..." link.

PyCharm will ask you where you want to initialize the new repository. Make sure you're picking the right folder.

As soon as you press the "OK" button, the "Version Control" tab will change to a "Git" tab.

At it's current state, there are no commits. Before you make your first commit, I'd suggest you add a ".gitignore" file so that no unwanted file gets to the repository.

To generate a new gitignore file, head over to gitignore.io website. You can generate gitignore files for a large number of technologies from this website.

You write the name of the technologies that you want to generate the file for. I usually go with "Python", "PyCharm" and hit the "Create" button.

The website will display the content of your desired ".gitignore" file. Select and copy everything from there and go back to PyCharm.

To simulate that, create a new file in your project by right clicking on the "HelloWorld" project name and selecting "File" under the "New" sub menu.

Name your file ".gitignore" and press enter. PyCharm will ask whether you want to add this file to Git or not. Click on Add and then paste the copied content.

At this moment, your repository doesn't have any commits. To create a new commit, click on the "Commit local changes" link or switch to the "Commit" tab.

Since this is your first commit, check all "Changes" and "Unversioned Files" from the commit tab.

Since this is your first commit, put a descriptive commit message such as "Initial commit" and press the "Commit" button to finalize.

You've successfully made a commit to your local repository. You can now see all the commits under the master branch in detail.

Now it's time to publish this repository on GitHub. To do so, create a new repository under your GitHub account.

Then copy the SSH link to this repository. If you do not have SSH configured for your project, you may use the HTTPS link but I'd highly recommend SSH.

Now go back to PyCharm and look at the top right corner. Besides where it says Git, you'll find a few signs.

The downwards blue arrow will pull code from your remote repository, the tick sign will create a new commit, the upwards green arrow will push code.

The clock icon will show your commit history and finally the looped back arrow will revert your changes. Click on the push arrow and a new window will pop up.

Click on the "Define remote" link and inside the URL input box, paste the link you've copied from GitHub. Press the OK button and wait until the process ends.

If everything goes fine, PyCharm will give you a "Push" button. It shouldn't take more than a few seconds to push the code to your remote repository.

If you're using HTTPS instead of SSH, you may have to provide your GitHub email and password on every push.

Once done, visit your remote repository and refresh the page to see if the changes have been pushed correctly or not.

Now you can commit and push your code to GitHub right from your IDE every time you make any significant change.

For example, delete the "library.py" file and update the code inside the "main.py" file to print out "Hello, World!" on the console.

def main():

print("Hello, World!")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Hello, World!Once you've made the changes, switch to the commit tab and you'll see all the uncommitted changes.

Make sure you've checked all the changes you want to commit. Write a descriptive commit message.

Then instead of just committing, try the "Commit and Push..." button this time. A new window will show up.

If everything looks good to you, click on the Push button and wait for the process to finish.

Remember, if you're using HTTPS you may have to reenter your email and password on every push.

You can check your remote repository on GitHub to make sure that the push has been done correctly.

You can do a lot more in terms of version controlling within PyCharm such as handling pull requests, but I'll leave those out for a later time.

How to Work With Variables and Different Types of Data in Python

A variable is an entity that can take on different values of different types. It's a named location in your computer's memory.

To create a new variable in Python, you just need to type out the name of the variable, followed by an equal sign and the value.

def main():

book = 'Dracula'

author = 'Bram Stoker'

release_year = 1897

goodreads_rating = 4.01

print(book)

print(author)

print(release_year)

print(goodreads_rating)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Dracula

# Bram Stoker

# 1897

# 4.01When it comes to naming your variable, the PEP 8 - Style Guide for Python says:

Function names should be lowercase, with words separated by underscores as necessary to improve readability.

And

Variable names follow the same convention as function names.

The guide also says:

Never use the characters ‘l’ (lowercase letter el), ‘O’ (uppercase letter oh), or ‘I’ (uppercase letter eye) as single character variable names. In some fonts, these characters are indistinguishable from the numerals one and zero. When tempted to use ‘l’, use ‘L’ instead.

As long as you're keeping these guidelines in mind, declaring variables in Python is very straightforward.

Instead of declaring the variables in separate lines, you can declare them in one go as follows:

def main():

book, author, release_year, goodreads_rating = 'Dracula', 'Bram Stoker', 1897, 4.01

print(book)

print(author)

print(release_year)

print(goodreads_rating)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Dracula

# Bram Stoker

# 1897

# 4.01

All you have to do is write the individual variable names in a single line using commas as separators.

Then after the equal sign you have to write the corresponding values in the same order as their names again using commas as separators.

In fact, you can also print them all out in one go. The print() method can take multiple parameters separated by commas.

def main():

book, author, release_year, goodreads_rating = 'Dracula', 'Bram Stoker', 1897, 4.01

print(book, author, release_year, goodreads_rating)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Dracula Bram Stoker 1897 4.01These parameters are then printed on the terminal in a single line using spaces for separating each of them.

Speaking of the print() method, you can use the + sign to add variables with strings inside a print method:

def main():

book, author, release_year, goodreads_rating = 'Dracula', 'Bram Stoker', 1897, 4.01

print(book + ' is a novel by ' + author + ', published in ' + release_year + '. It has a rating of ' + goodreads_rating + ' on goodreads.')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to strIf you try to run this code you'll get a TypeError that says Python can concatenate or add together strings not integers.

In the code snippet above, book, author, release_year, and goodreads_rating are all variables of different types.

The book and author variables are strings. The release_year is an integer and finally the goodreads_rating variable is a floating point number.

Whenever Python encounters a + sign in front of a numeric type, it assumes that the programmer may be performing an arithmetic operation.

The easiest way to solve this problem is to convert the numeric types to strings. You can do that by calling the str() method on the numeric variables.

def main():

book, author, release_year, goodreads_rating = 'Dracula', 'Bram Stoker', 1897, 4.01

print(book + ' is a novel by ' + author + ', published in ' + str(release_year) + '. It has a rating of ' + str(goodreads_rating) + ' on goodreads.')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Dracula is a novel by Bram Stoker, published in 1897. It has a rating of 4.01 on goodreads.That's better – but you can make that line of code even more readable by using a f string.

def main():

book, author, release_year, goodreads_rating = 'Dracula', 'Bram Stoker', 1897, 4.01

print(f'{book} is a novel by {author}, published in {release_year}. It has a rating of {goodreads_rating} on goodreads.')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Dracula is a novel by Bram Stoker, published in 1897. It has a rating of 4.01 on goodreads.You can turn a regular string to a f string by putting a f in front of it and suddenly you can write variable names inside curly braces right within the string itself.

There is one last thing that's bugging me, and that's the length of the line of code itself. Fortunately you can split long strings into multiple shorter ones as follows:

def main():

book, author, release_year, goodreads_rating = 'Dracula', 'Bram Stoker', 1897, 4.01

print(f'{book} is a novel by {author}, published in {release_year}.'

f' It has a rating of {goodreads_rating} on goodreads.')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Dracula is a novel by Bram Stoker, published in 1897. It has a rating of 4.01 on goodreads.Now that's how a good piece of Python code should look. I'd suggest you try to make your code readable from the very beginning – you'll thank me later for that.

Other than int and float, there is another numeric type called complex in Python. It was specifically designed for dealing with numbers like 500+2j.

There are also boolean data that can hold the value True or False and nothing else. You can actually ask Python questions and it'll answer in boolean.

Throughout this book you'll not see complex numbers in action and booleans will come into play much later. So for now, lets focus on simple numbers and strings.

How to Work With Simple Numbers in Python

Simple numbers in Python are of two types. Whole numbers are integers and numbers with floating points in them are floats.

In Python, you can represent integers using four different bases. These are decimal, hexadecimal, octal, and binary.

| Base | Representation |

|---|---|

| Decimal | 404 |

| Hexadecimal | 0x194 |

| Octal | 0o624 |

| Binary | 0b000110010100 |

So you can represent the value of 404 in hexadecimal, octal, or binary by prefixing the corresponding value with 0x, 0o, or 0b respectively.

On the other hand you can represent floats with the precision of up to 15 significant digits in Python. Any digit after the 15th place may be inaccurate.

There are six different arithmetic operations that you can perform on any of the simple numeric types. The simplest of the bunch are addition and subtraction.

def main():

num_1 = 15

num_2 = 12

print(f'sum of num_1 and num_2 is: {num_1 + num_2}')

print(f'difference of num_1 and num_2 is: {num_1 - num_2}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# sum of num_1 and num_2 is: 27

# difference of num_1 and num_2 is: 3In case of a subtraction operation, the result will be negative if the second operand is larger than the first one.

def main():

num_1 = 15

num_2 = 12

print(f'difference of num_2 and num_1 is: {num_2 - num_1}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# difference of num_2 and num_1 is: -3Similarly you can perform multiplication and division operations using their corresponding operators.

def main():

num_1 = 15

num_2 = 12

print(f'product of num_1 and num_2 is: {num_1 * num_2}')

print(f'quotient of num_1 and num_2 is: {num_1 / num_2}')

print(f'floored quotient of num_1 and num_2 is: {num_1 // num_2}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# product of num_1 and num_2 is: 180

# quotient of num_1 and num_2 is: 1.25

# floored quotient of num_1 and num_2 is: 1

Keep in mind that you can not divide a number by zero in Python. If you attempt that, you'll get a ZeroDivisionError error (more on that later).

Output from a division operation will always be a float value, unless you perform a floored division by using two division operators.

def main():

num_1 = 15

num_2 = 12

print(f'floored quotient of num_1 and num_2 is: {num_1 // num_2}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# floored quotient of num_1 and num_2 is: 1

In this case the result will be rounded off to the nearest integer low – so, for example, 0.25 will be lost. So only perform this operation when such loss of data is permissible.

The last operation to discuss is finding the remainder of a division operation.

def main():

num_1 = 15

num_2 = 12

print(f'remainder of num_1 / num_2 is: {num_1 % num_2}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# remainder of num_1 / num_2 is: 3

This operation is also called a modulo or modulus operation. So if someone mentions the modulo or modulus operator, they're referring to the percent sign.

You can turn an unsigned number into a negative one just by adding a - sign in front of it. You can also freely convert between integer to float and vice versa.

def main():

float_variable = 1.25

integer_variable = 55

print(f'{float_variable} converted to an integer is: {int(float_variable)}')

print(f'{integer_variable} converted to a float is: {float(integer_variable)}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# 1.25 converted to an integer is: 1

# 55 converted to a float is: 55.0

Loss of data in case of a float to integer conversion is inevitable, so be careful. You can use the int() and float() methods on strings as well (more on that later).

Any arithmetic operation involving a float operand will always produce a float result, unless converted to integer explicitly.

def main():

float_variable = 5.0

integer_variable = 55

print(f'the sum of {float_variable} and {integer_variable} is: {float_variable + integer_variable}')

print(f'the sum of {float_variable} and {integer_variable} '

f'converted to integer is: {int(float_variable + integer_variable)}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# the sum of 5.0 and 55 is: 60.0

# the sum of 5.0 and 55 converted to integer is: 60

If you ever want to get the absolute value of a signed value you can do so using the abs() method.

def main():

num_1 = -5.8

print(f'the absolute value of {num_1} is: {abs(num_1)}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# the absolute value of -5.8 is: 5.8

There is a similar method pow(x, y) that you can use to apply x as the power of y like this.

def main():

x = 2

y = 3

print(f'{2} to the power of {3} is: {pow(2, 3)}')

print(f'{2} to the power of {3} is: {2 ** 3}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# 2 to the power of 3 is: 8

# 2 to the power of 3 is: 8

You can perform the same operation using two multiplication operators but I always prefer the pow() method.

Finally there is the divmod() method that you can use to combine the division and modulo operation.

def main():

num_1 = 8

num_2 = 2

print(f'division and modulus of {num_1} and {num_2} is: {divmod(num_1, num_2)}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# division and modulus of 8 and 2 is: (4, 0)

The method returns a tuple of numbers (more on that later). The first one is the result of the division and the second one is the result of the modulo operation.

These are the basic operations you can perform on simple numbers right from the get go. But you can do much more once you start to pull in the built-in modules.

How to Take Inputs From Users in Python

Learning how to take input from a user is an important milestone because it lets you create programs that a human being can interact with.

Unlike many other programming languages, taking user inputs in Python is very straightforward.

def main():

name = input('What is your name? ')

print(f'Nice to meet you {name}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# What is your name? Farhan

# Nice to meet you Farhan

The built-in input() method does exactly what it sounds like. The method accepts a single parameter prompt which is of string type.

Whatever you write as the value of this parameter will be shown in the console – like in this case, "What is your name?" is the prompt.

Once the user writes something on the console and presses enter, the input method will return that as a string.

You can save that string to any variable like I've saved the name inside the name variable. Even if the user inputs a number, input() will return that as a string.

def main():

name = input('What is your name? ')

age = input(f'How old are you {name}? ')

current_year = input(f'What year is this again? ')

print(f'If my calculations are right, you were born in {current_year - age}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# What is your name? Farhan

# How old are you Farhan? 27

# What year is this again? 2023

# TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for -: 'str' and 'str'Even though Python is taking all the user inputs correctly, it fails to calculate the user's birth year because arithmetic operations are not a good fit for strings.

To solve this problem, you just have to convert the user inputs to numeric types using the int() or float() functions as needed.

def main():

name = input('What is your name? ')

age = int(input(f'How old are you {name}? '))

current_year = int(input(f'What year is this again? '))

print(f'If my calculations are right, you were born in {current_year - age}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# What is your name? Farhan

# How old are you Farhan? 27

# What year is this again? 2023

# If my calculations are right, you were born in 1996

There you go, works like a charm. You can perform this conversion at any point in the code. It's not mandatory to convert them right at the beginning.

def main():

temperature_in_celsius = input('What is the temperature in celsius? ')

temperature_in_fahrenheit = (float(temperature_in_celsius) * 1.8) + 32

print(f'{temperature_in_celsius} degree celsius is equivalent to {temperature_in_fahrenheit} degree fahrenheit.')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# What is the temperature in celsius? 32

# 32 degree celsius is equivalent to 89.6 degree fahrenheit.

This program can convert temperature from Celsius to Fahrenheit. In this program, I didn't convert the input from string to a numeric type right away.

I performed the conversion during the calculation leaving the original input variable intact. Also notice the use of float() instead of the int() function.

How to Work With Strings in Python

You've already seen examples of strings in the previous sections – but there is a lot more that you need to learn about strings.

In Python, anything enclosed within a set of single, double, or triple quotes is a string. These are sequences of bytes representing Unicode characters.

def main():

book = 'Dracula'

author = "Bram Stoker"

print('Title:', book)

print('Author:', author)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Title: Dracula

# Author: Bram Stoker

Declaring a string with single or double quotes makes no difference whatsoever. But based on the scenario, you may have to choose on over the other.

For example, if you have an apostrophe within your sentence, you may want to use double quotes.

def main():

question = "What's your name?"

print(question)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# What's your name?

The opposite can also occur. For example, when you have a direct quote within your string:

def main():

sentence = 'Harriet Jacobs writes, "She sat down, quivering in every limb"'

print(sentence)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Harriet Jacobs writes, "She sat down, quivering in every limb"

You can also go for escape sequences if you want to, but the PEP 8 - Style Guide for Python Code recommends avoiding the usage of back slashes within strings.

Triple quotes are a different case altogether. You can put multi-line strings within triple quotes and Python will preserve the white spaces as well.

def main():

synopsis = """Dracula comprises journal entries, letters, and telegrams written by the main characters.

It begins with Jonathan Harker, a young English lawyer, as he travels to Transylvania.

Harker plans to meet with Count Dracula, a client of his firm, in order to finalize a property transaction.

When he arrives in Transylvania, the locals react with terror after he discloses his destination: Castle Dracula.

Though this unsettles him slightly, he continues onward.

The ominous howling of wolves rings through the air as he arrives at the castle.

When Harker meets Dracula, he acknowledges that the man is pale, gaunt, and strange.

Harker becomes further concerned when, after Harker cuts himself while shaving, Dracula lunges at his throat.

Soon after, Harker is seduced by three female vampires, from whom he barely escapes.

He then learns Dracula’s secret—that he is a vampire and survives by drinking human blood.

Harker correctly assumes that he is to be the count’s next victim.

He attacks the count, but his efforts are unsuccessful.

Dracula leaves Harker trapped in the castle and then, along with 50 boxes of dirt, departs for England."""

print('Synopsis:', synopsis)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Synopsis: Dracula comprises journal entries, letters, and telegrams written by the main characters.

# It begins with Jonathan Harker, a young English lawyer, as he travels to Transylvania.

# Harker plans to meet with Count Dracula, a client of his firm, in order to finalize a property transaction.

# When he arrives in Transylvania, the locals react with terror after he discloses his destination: Castle Dracula.

# Though this unsettles him slightly, he continues onward.

# The ominous howling of wolves rings through the air as he arrives at the castle.

# When Harker meets Dracula, he acknowledges that the man is pale, gaunt, and strange.

# Harker becomes further concerned when, after Harker cuts himself while shaving, Dracula lunges at his throat.

# Soon after, Harker is seduced by three female vampires, from whom he barely escapes.

# He then learns Dracula’s secret—that he is a vampire and survives by drinking human blood.

# Harker correctly assumes that he is to be the count’s next victim.

# He attacks the count, but his efforts are unsuccessful.

# Dracula leaves Harker trapped in the castle and then, along with 50 boxes of dirt, departs for England.

So if you ever want to print out a multi line string while preserving the white spaces, go for triple quotes.

You can declare a triple quoted string using three single quotes but the PEP 8 - Style Guide for Python Code recommends the usage of three double quotes.

There is a lot more to learn about strings, but I'd like to introduce you to some other sequence types in Python.

What Are the Sequence Types in Python?

In Python, there are three sequence types. They are lists, tuples, and ranges. I'll start with the lists because it's probably the most utilized sequence type in Python.

Lists in Python

A list in Python is exactly what it sounds like: a collection of data stored sequentially on the computer's memory.

You can create a new list in Python by writing out its name followed by an equal sign, followed by the values to store enclosed in square brackets:

def main():

horror_books = ['Dracula', 'Carmilla', 'The Imago Sequence']

print(horror_books)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# ['Dracula', 'Carmilla', 'The Imago Sequence']

In this example, horror_books is a list of strings. But you can create lists of integers, floats, or even of mixed types.

def main():

a_random_list = ['Dracula', 1, 5.7, 'Carmilla']

print(a_random_list)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# ['Dracula', 1, 5.7, 'Carmilla']

Though this is perfectly valid, you may find yourself creating lists of the same types more often.

Lists in Python are mutable. This means you can modify a list after its creation. For example, you can use the pop() method to get rid of the last value in a list.

def main():

horror_books = ['Dracula', 'Carmilla', 'The Imago Sequence']

print(horror_books.pop())

print(horror_books)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# The Imago Sequence

# ['Dracula', 'Carmilla']As you can see, the pop() method returns the last value from the list and gets rid of it. Like pop() there is the append() method for inserting new item to the list.

def main():

horror_books = ['Dracula', 'Carmilla', 'The Imago Sequence']

print(horror_books)

horror_books.append('The Exorcist')

print(horror_books)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# ['Dracula', 'Carmilla', 'The Imago Sequence']

# ['Dracula', 'Carmilla', 'The Imago Sequence', 'The Exorcist']

As you can see from the method name, it adds the new item at the end of the list. Given their mutable nature, lists can also be sorted.

Feel free to check out the following article written by my colleague Dionysia Lemonaki here on freeCodeCamp about how to sort lists in Python:

Tuples in Python

Lists are not the only sequence type in Python. The closest sibling of lists in Python are tuples.

You can create a new tuple in Python by writing out its name followed by an equal sign, then enclosing inside a pair of parenthesis the values you want to store.

def main():

horror_books = ('Dracula', 'Carmilla', 'The Imago Sequence')

print(horror_books)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# ('Dracula', 'Carmilla', 'The Imago Sequence')Just like lists, you can also mix and match different types of data within a single tuple as you see fit.

def main():

a_random_list = ('Dracula', 1, 5.7, 'Carmilla')

print(a_random_list)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# ('Dracula', 1, 5.7, 'Carmilla')

The most glaring dissimilarity between a list and a tuple is the fact that a tuple is immutable. So there's no popping and appending for us this time.

Ranges in Python

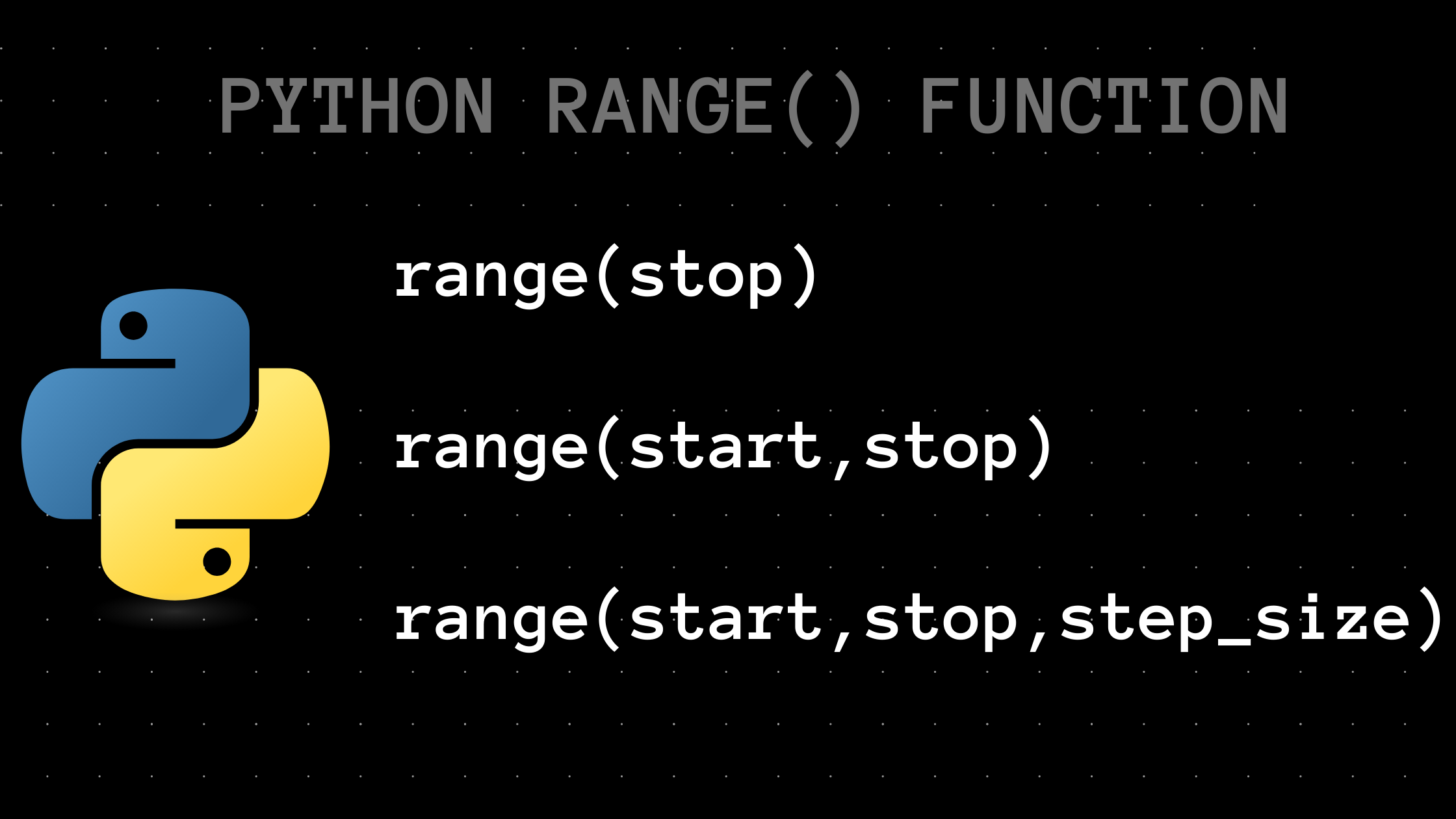

The final sequence type that you're going to learn about in this section is a range. A range in Python is just a range of numbers.

You can create a range by calling the range() method and it'll return a range of numbers. You can call the method in a few different ways.

The most common is by passing a single number as a parameter. In this case, the method will treat that number as the end of the range and 0 as the start.

def main():

a_range = range(10)

print(a_range)

list_a_range = list(a_range)

print(list_a_range)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# range(0, 10)

# [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

# (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9)

Printing out a range as is won't give you much information. You'll have to convert the range to a list or a tuple by either calling the list() or tuple() method.

Once converted, you can then print out the entire range to the console. Notice how 10 or the number passed to the range() method is not included in the range.

The second way of calling the method is by supplying both the starting and ending numbers for the range.

def main():

a_range = range(5, 15)

print(a_range)

list_a_range = list(a_range)

print(list_a_range)

tuple_a_range = tuple(a_range)

print(tuple_a_range)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# range(5, 15)

# [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]

# (5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14)

Once again, the number you pass as the ending for the range will not be included in the resultant range.

The third and final way to call the method is by also defining a step. For example, imagine you want a range comprising of all the odd numbers within 1 to 10.

def main():

a_range = range(1, 10, 2)

print(a_range)

list_a_range = list(a_range)

print(list_a_range)

tuple_a_range = tuple(a_range)

print(tuple_a_range)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# range(1, 10, 2)

# [1, 3, 5, 7, 9]

# (1, 3, 5, 7, 9)

Since the value of step is 2 in this case, the range will begin with 1 but then skip every second number.

It may take some time to wrap your head around this concept but practicing with different step values will help.

Or you can read the following article written by Bala Priya C:

How Indexing Works in Python

One of the most important concepts regarding sequence types that you need to understand is indexing.

You see, each element in a sequence has a number attached to it that expresses its position in the list called an index. These indices are 0 based.

This diagram represents our list of horror books. The index of the first book is 0 – this means that the first element is at the 0th place.

The second one is at the 1st place and the third one is at the 2nd place. This zero-based indexing is may seem confusing at first but you'll get the hang of it.

The most basic usage of a index is to access its corresponding value from the sequence.

def main():

horror_books = ['Dracula', 'Carmilla', 'The Imago Sequence']

print(horror_books[0])

print(horror_books[1])

print(horror_books[2])

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Dracula

# Carmilla

# The Imago SequenceYou can also use negative numbers as indices but in that case the counting will start from the end.

def main():

books = ['Dracula', 'Frankenstein', 'The Omen', 'The Exorcist', 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow',

'And Then There Were None', 'The ABC Murders', 'The Valley of Fear']

print(books[0])

print(books[1])

print(books[-1])

print(books[2])

print(books[-2])

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Dracula

# Frankenstein

# The Valley of Fear

# The Omen

# The ABC MurdersThe 0th element in a list will always be the first one. Now if you access the element on the 1st position you get "Frankenstein".

But if you try to access the element on the -1st position, you get "The Valley of Fear" because that's the second item in reverse.

The element on the 2nd position is "The Omen" but the element at the -2nd position is "The ABC Murders" because that's the third item in reverse.

If you're finding it hard to wrap your head around, imagine the list like a clock.

Here the outer number is the negative index and the inner number is the positive index. If you try to match the outputs against this imaginary clock, it should be easier to understand.

What Are the Iterable Types and How to Use them for Loops in Python

So far you've learned about creating collections of data and accessing them one by one. That's cool but there is something cooler.

Imagine you have a list or some other type of that contains a bunch of numbers.

Now you want to multiply each number in that list by two, insert the multiplied numbers in a new list, and print out the list on the terminal.

This is an excellent use case for the for statement in Python. Let's begin by first iterating through each number in a given list.

def main():

random_numbers = [6, 1, 3, 8, 0, 9, 12, 3, 4, 0, 54, 8, 100, 55, 60, 70, 85]

for number in random_numbers:

print(number)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# 6

# 1

# 3

# 8

# 0

# 9

# 12

# 3

# 4

# 0

# 54

# 8

# 100

# 55

# 60

# 70

# 85You start by writing out the word for followed by a variable name. I've used number but you can use anything that makes sense to you.

Although you write it as for number, Python reads it as for each number and wonders where are these numbers staying?

That's when you say in followed by the name of the sequence, random_numbers in this case.

Now Python understands that you want to do something with each number in the random_numbers sequence, but what?

That's what you have to write out after the colon and be very careful about the indentation. Anything indented one level after the for loop declaration is considered the loop body.

Inside the for loop you can write whatever you want to do with the current value of the number variable.

Since there are 17 numbers in the sequence, the loop will run 17 times and each time it'll have a new value.

It'll start at index 0 which has the value of 6 and go through index 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and so on.

On each iteration, it'll save the value of the index it's currently working on inside the number variable and print it out. Hence you get the long list of numbers.

Instead of printing out the original value, you can multiply it by 2 and print out the resultant value instead.

def main():

random_numbers = [6, 1, 3, 8, 0, 9, 12, 3, 4, 0, 54, 8, 100, 55, 60, 70, 85]

for number in random_numbers:

print(number * 2)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# 12

# 2

# 6

# 16

# 0

# 18

# 24

# 6

# 8

# 0

# 108

# 16

# 200

# 110

# 120

# 140

# 170

Now you're getting the multiplied values. The final task is to insert these multiplied values in a new list and print out the new list itself.

def main():

random_numbers = [6, 1, 3, 8, 0, 9, 12, 3, 4, 0, 54, 8, 100, 55, 60, 70, 85]

multiplied_random_numbers = []

for number in random_numbers:

multiplied_random_numbers.append(number * 2)

print(multiplied_random_numbers)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# [12, 2, 6, 16, 0, 18, 24, 6, 8, 0, 108, 16, 200, 110, 120, 140, 170]For that you'll need an empty list. Then, after multiplying the number, you can simply call the append() method on the new list and pass the multiplied value.

Finally, make sure that you're putting the print statement outside of the loop body otherwise you'll end up printing out the list 17 times.

The for loop works with all the sequence types and any iterable type in the Python language. What is an iterable type, I hear you ask.

Well, any object that has the __iter__() method is considered an iterable in Python.

You can call the dir() function on any object to list out all its methods and properties. Take the random_numbers list as an example.

def main():

random_numbers = [6, 1, 3, 8, 0, 9, 12, 3, 4, 0, 54, 8, 100, 55, 60, 70, 85]

print(dir(random_numbers))

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# ['__add__', '__class__', '__class_getitem__', '__contains__', '__delattr__', '__delitem__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getitem__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__iadd__', '__imul__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__iter__', '__le__', '__len__', '__lt__', '__mul__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__reversed__', '__rmul__', '__setattr__', '__setitem__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', 'append', 'clear', 'copy', 'count', 'extend', 'index', 'insert', 'pop', 'remove', 'reverse', 'sort']You can see some familiar methods such as append, count, and index but most importantly it has the __iter__ method.

As you keep working in Python you'll eventually remember the types supported by the for loop but you can always use the dir() method on a object to find out.

How to Use While Loops in Python

There is another type of loop in Python known as the while loop. Unlike for, a while loop can execute a statement as long as a given condition evaluates to true.

def main():

number = 1

while number < 11:

print(number)

number += 1

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# 1

# 2

# 3

# 4

# 5

# 6

# 7

# 8

# 9

# 10Here you have a variable number with the value 11 and a while loop that prints out the value of number, then increases it by 1.

A while loop starts by writing out while followed by the condition. Then you write the loop body starting from the next line after the colon.

for loops are useful when you're trying to access every element inside an iterable. while loops are useful when you want to repeat the same set of instructions an arbitrary number of times.

The line number += 1 is another way to write number = number + 1 and it's very commonly used by programmers across different programming languages.

How to Write Nested Loops in Python

You can also nest one loop inside another. For example, look at the following code that prints out multiplication tables:

def main():

for x in range(1, 6):

print()

for y in range(1, 11):

print(f"{x} x {y} = {x * y}")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

#

# 1 x 1 = 1

# 1 x 2 = 2

# 1 x 3 = 3

# 1 x 4 = 4

# 1 x 5 = 5

# 1 x 6 = 6

# 1 x 7 = 7

# 1 x 8 = 8

# 1 x 9 = 9

# 1 x 10 = 10

#

# 2 x 1 = 2

# 2 x 2 = 4

# 2 x 3 = 6

# 2 x 4 = 8

# 2 x 5 = 10

# 2 x 6 = 12

# 2 x 7 = 14

# 2 x 8 = 16

# 2 x 9 = 18

# 2 x 10 = 20

#

# 3 x 1 = 3

# 3 x 2 = 6

# 3 x 3 = 9

# 3 x 4 = 12

# 3 x 5 = 15

# 3 x 6 = 18

# 3 x 7 = 21

# 3 x 8 = 24

# 3 x 9 = 27

# 3 x 10 = 30

#

# 4 x 1 = 4

# 4 x 2 = 8

# 4 x 3 = 12

# 4 x 4 = 16

# 4 x 5 = 20

# 4 x 6 = 24

# 4 x 7 = 28

# 4 x 8 = 32

# 4 x 9 = 36

# 4 x 10 = 40

#

# 5 x 1 = 5

# 5 x 2 = 10

# 5 x 3 = 15

# 5 x 4 = 20

# 5 x 5 = 25

# 5 x 6 = 30

# 5 x 7 = 35

# 5 x 8 = 40

# 5 x 9 = 45

# 5 x 10 = 50

To be honest, this is a very simple bit of code that makes use of a lot of the things you've already learned in this handbook.

To create a multiplication table we need two operands: one remains constant for the entire table and the other increases by 1 until it reaches 10.

Here, x represents the left operand or the constant one and y represents the right operand or the variable one.

The first loop iterates through a range of 1 to 5 and the second loop iterates through a range of 1 to 10.

Since the ending number of a range is exclusive, you need to put a number that is 1 higher than the desired ending number.

First the Python interpreter encounters the outer loop and starts executing it. While inside that loop, the value of x is 1.

The interpreter then encounters the inner loop and starts executing that. While inside the inner loop, the value of x remains 1 but the value of y increases in each iteration.

The inner loop is the body of the outer loop in this case, so the first iteration of the outer loop lasts until the inner loop finishes.

After finishing 10 iterations of the inner loop, the interpreter comes back to the outer loop and starts executing it once again.

This time the value of x becomes 2 since that's what comes next in the range.

Just like that, the outer loop executes 5 times and the inner loop executes 10 times for each of those iterations.

Like a lot of other concepts, wrapping your head around nested loops can be difficult, but practice will make things easier.

I'd suggest you go ahead and implement this program using while loops to test your understanding.

You can also take the two numbers from the user and print the multiplication table within that range.

For example, if the user puts 5 and 10 as inputs, then you'll print out the multiplication tables of all the numbers from 5 to 10.

You can nest loops to even deeper levels, but going deeper than two loops may cause performance issues so be careful with that.

What Are Some Common Sequence Type Operations in Python?

Assuming you remember the text sequence type (strings), you're now familiar with the four most popular Python sequence types.

So I think it's time for you to learn some common operations that you can perform on them. Let's begin, shall we?

How to Use the in Operator in Python

The in operator is the most common way of checking for any object's existence. For example, assume that you have a string and you want to check if it contains the word "red" or not.

def main():

a_string = 'Little Red Riding-Hood comes to me one Christmas Eve to give me information of the cruelty and ' \

'treachery of that dissembling Wolf who ate her grandmother. '

print('Red' in a_string)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# True

It's literally like asking Python, if the word Red is in the a_string variable. And Python will give you either True or False as an answer.

The in operator is not exclusive to strings. You can actually use it on any other collection type such as lists, tuples, and ranges.

def main():

books = ['Dracula', 'Frankenstein', 'The Omen', 'The Exorcist', 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow']

movies = ('A Christmas Carol', 'The Sea Beast', 'Enchanted', 'Pinocchio', 'The Addams Family')

numbers = range(10)

print('A Christmas Carol' in books)

print('Enchanted' in movies)

print(5 in numbers)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# False

# True

# True

A Christmas Carol doesn't exist in the books list so it's a False statement. The other two statements are right, so they're True.

You may also want to find out about the absence of an object. For that, you can use the not operator in conjunction with the in operator.

def main():

books = ['Dracula', 'Frankenstein', 'The Omen', 'The Exorcist', 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow']

movies = ('A Christmas Carol', 'The Sea Beast', 'Enchanted', 'Pinocchio', 'The Addams Family')

numbers = range(10)

print('A Christmas Carol' not in books)

print('Enchanted' not in movies)

print(15 not in numbers)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# True

# False

# True

A Christmas Carol doesn't exist in the books list, so the first statement evaluates to true. The second one evaluates to false because Enchanted is present in the movies list.

The last one is self explanatory at this point. The in and not in operators come in very handy when working with conditional statements.

How to Use the + and * Operators with Sequence Types in Python

You've already learned about + and * as arithmetic operators – but in the case of sequence types, they play a very different role.

The + operator lets you merge two sequences together.

def main():

books = ['Dracula', 'Frankenstein', 'The Omen', 'The Exorcist', 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow']

more_books = ['And Then There Were None', 'The ABC Murders', 'The Valley of Fear', 'The Hound of the Baskervilles', 'The Chestnut Man']

print(books + more_books)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# ['Dracula', 'Frankenstein', 'The Omen', 'The Exorcist', 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow', 'And Then There Were None', 'The ABC Murders', 'The Valley of Fear', 'The Hound of the Baskervilles', 'The Chestnut Man']As you can see, the operator has appended the content of the books list to the content of the more_books list.

The * operator, on the other hand, makes multiple copies of a given sequence.

def main():

books = ['Dracula', 'Frankenstein', 'The Omen', 'The Exorcist', 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow']

print(books * 2)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# ['Dracula', 'Frankenstein', 'The Omen', 'The Exorcist', 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow', 'Dracula', 'Frankenstein', 'The Omen', 'The Exorcist', 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow']So multiplying the books list by 2 gives us all the 5 books in the list twice. These operators work the same for tuples, strings, ranges or any other sequence types.

How to Use the len(), min(), and max() Functions in Python

The len() function can return the length of a given sequence. And the min() and max() functions can return the minimum and maximum value in a given sequence, respectively.

def main():

random_numbers = [6, 1, 3, 8, 0]

print(len(random_numbers))

print(min(random_numbers))

print(max(random_numbers))

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# 5

# 0

# 8Since there are 5 elements in the list, 5 is the output from the len() function call.

The smallest value in the list is 0 and the largest value is 8 which are the outputs from the min() and max() function calls, respectively.

Depending on the type of programs you end up writing in the future, these three functions can prove to be some of the most useful ones.

What Are Some String Type Operations in Python?

In the previous section, you've learned about some common operations that you can perform on any sequence type including strings.

However, the text sequence type aka strings have some special operations available to them.

In this chapter I'll introduce you to some of the most common string methods. Keep in mind that this is not a definitive list.

Although each of the methods I'm going to teach you performs a different task, they have one thing in common. None of them modifies a given string variable in place, but rather returns a new, modified copy.

If you want to learn about all the available string methods, feel free to consult the official Python documentation.

Also remember it's not a matter of just going through each method and memorizing their usage.

It's about knowing what works best in a given scenario and coming up with clever solutions. And that requires practice.

How to Capitalize Strings in Python

The first method you're going to learn is called capitalize() and it does what it sounds like.

def main():

country_name = 'bangladesh'

print(country_name.capitalize())

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Bangladesh

As you can see from the code snippet above, the capitalize() method turns the first letter of the word to a capital letter.

This is simple, but let's try this on a string with multiple words in it – a sentence perhaps.

def main():

book_name = 'the house of silk'

print(book_name.capitalize())

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# The house of silk

Although the method did its job, there is slight problem. Depending on what you're trying to achieve, you may expect the first letter of each word to be capitalized.

That's where the title() method comes in. This method returns a title cased version of a given string.

def main():

book_name = 'the house of silk'

print(book_name.title())

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# The House Of Silk

But there is still an issue. Take the following string with apostrophes for example.

def main():

book_name = "alice's adventures in wonderland"

print(book_name.title())

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Alice'S Adventures In Wonderland

As you can see, the title() method treats the s following the apostrophe as a separate word and capitalizes it.

Regarding this issue, the official documentation states:

The algorithm uses a simple language-independent definition of a word as groups of consecutive letters. The definition works in many contexts but it means that apostrophes in contractions and possessives form word boundaries.

The capwords() helper function can solve this issue. This function breaks the string into multiple words based on the spaces between them, capitalizes the words, joins them back into a string and returns that to the user.

from string import capwords

def main():

book_name = "alice's adventures in wonderland"

print(capwords(book_name))

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Alice's Adventures In Wonderland

Pay attention to the import statement at the top. The capwords() function is not a method within the string type but a function that resides inside the string module.

You'll learn about modules and imports in more details later on. For now, just roll with it. Although the function uses spaces to split words, you can overwrite it.

from string import capwords

def main():

address = 'house 42, road 02, wonderland'

print(capwords(address, ', '))

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# House 42, Road 02, Wonderland

As you can see, in this case the string has multiple parts divided by a comma followed by a space.

The capwords() function can take a custom delimiter as its second parameter. You can pass any string as the delimiter.

Finally, there is the istitle() method that can check whether a given string is in title case or not.

def main():

book_name = 'hearts in atlantis'

print(f'Is "{book_name}" in title case? {book_name.istitle()}')

print(f'Is "{book_name.title()}" in title case? {book_name.title().istitle()}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Is "hearts in atlantis" in title case? False

# Is "Hearts In Atlantis" in title case? True

However, keep in mind that the istitle() method doesn't work with the capwords() helper function.

How to Convert Strings to Lower Case or Upper Case in Python

Apart from capitalization, you may want to convert an entire string to upper case or lower case. You can do that by using the upper() and lower() methods in Python.

def main():

book_name = 'moriarty'

print(book_name.upper())

another_book_name = 'DRACULA'

print(another_book_name.lower())

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# MORIARTY

# dracula

There are also the isupper() and islower() methods to check whether a given string is already in either of the letter cases or not.

def main():

book_name = 'moriarty'

print(book_name)

print(f'Is {book_name} in upper case? {book_name.isupper()}')

print(f'Is {book_name} in lower case? {book_name.islower()}')

another_book_name = 'DRACULA'

print(another_book_name)

print(f'Is {another_book_name} in upper case? {another_book_name.islower()}')

print(f'Is {another_book_name} in lower case? {another_book_name.isupper()}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# moriarty

# Is moriarty in upper case? False

# Is moriarty in lower case? True

# DRACULA

# Is DRACULA in upper case? True

# Is DRACULA in lower case? False

There is one last method called casefold() which is kind of a more aggressive version of the lower() method.

According to the official documentation:

Casefolding is similar to lowercasing but more aggressive because it is intended to remove all case distinctions in a string. For example, the German lowercase letter 'ß' is equivalent to "ss". Since it is already lowercase, lower() would do nothing to 'ß'; casefold() converts it to "ss".

The usage of this method is identical to the lower() method.

def main():

book_name = 'DRACULA'

print(book_name.casefold())

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# dracula

These three methods are fine and dandy, but what if you don't want to use any of these particular methods and just want to switch the case of a given string?

The swapcase() method can do just that.

def main():

book_name = 'HEARTS IN ATLANTIS'

print(book_name.swapcase())

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# hearts in atlantis

As you can see, the method has converted the book name into lower case from upper case.

How to Count the Number of Occurrences of a Substring in a String in Python

If you want to find out the number of occurrences of a substring within a string, you can use the count() method in Python.

def main():

paragraph = '''At three in the morning the chief Sussex detective, obeying the urgent call from Sergeant Wilson of

Birlstone, arrived from headquarters in a light dog-cart behind a breathless trotter. By the five-forty train in

the morning he had sent his message to Scotland Yard, and he was at the Birlstone station at twelve o'clock to

welcome us. White Mason was a quiet, comfortable-looking person in a loose tweed suit, with a clean-shaved,

ruddy face, a stoutish body, and powerful bandy legs adorned with gaiters, looking like a small farmer,

a retired gamekeeper, or anything upon earth except a very favourable specimen of the provincial criminal

officer.'''

substring = 'morning'

print(f'The substring "{substring}" shows up {paragraph.count(substring)} times in the paragraph.')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# The substring "morning" shows up 2 times in the paragraph.

If you call the count() method without passing anything to it, the method will return the number of empty spaces in the given string.

How to Split and Join Strings in Python

You can actually break a string into a list of words or join a list of words in a string in Python.

def main():

string = 'Holmes was certainly not a difficult man to live with'

word_list = string.split()

print(word_list)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# ['Holmes', 'was', 'certainly', 'not', 'a', 'difficult', 'man', 'to', 'live', 'with']If you call the split() method without any parameters, it'll split the given string into words using the spaces as separators.

You can override that by passing a custom separator and also fix the number of splits you want.

def main():

string = 'Holmes,was,certainly,not,a,difficult,man,to,live,with'

word_list = string.split(',', 5)

print(word_list)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# ['Holmes', 'was', 'certainly', 'not', 'a', 'difficult,man,to,live,with']

This time I've replaced the spaces in the source string with commas. I've also overridden the default separator with a comma and fixed the number of splits to five.

As you can see in the output, there are five splits and the rest of the string is kept unchanged as the sixth element in the list.

The split() method is good for using with data that has been intentionally delimited. Using it with natural text with punctuation may produce unexpected results.

The opposite of the split() method is join() and it works on any iterator type in Python.

def main():

word_list = ['Holmes', 'was', 'certainly', 'not', 'a', 'difficult', 'man', 'to', 'live', 'with']

string = ''

string = string.join(word_list)

print(string)

word_list = ['Holmes ', 'was ', 'certainly ', 'not ', 'a ', 'difficult ', 'man ', 'to ', 'live ', 'with']

string = ''

string = string.join(word_list)

print(string)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# Holmeswascertainlynotadifficultmantolivewith

# Holmes was certainly not a difficult man to live with

There you have it. Notice how the join() method didn't care about adding spaces as separator after each word in the first call.

So I appended a space with each word in the list and in the second call the line has become much more readable.

How to Write Conditional Statements in Python

This is where it gets interesting. In Python or in any other programming language you can make decisions based on conditions.

I hope you remember the boolean data type from a previous section – the one that can only hold True or False values.

Well, you can use a boolean with an if statement (a conditional statement) in Python to perform an action conditionally.

def main():

number = int(input('what number would you like to check?\n- '))

if number % 2 == 0:

print(f"{number} is even.")

else:

print(f"{number} is odd.")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# what number would you like to check?

# - 10

# 10 is even.

You start by writing out if followed by a condition and a colon. By condition, what I mean is a statement that evaluates to a boolean value (true or false).

You've been using the == operator since the beginning and already know that it checks whether the value on the left side of it is equal to the one in the right or not.

So, if you divide a given number by 2 and the remainder is 0, that's an even number – otherwise, it'll be odd.

You can use the if...else statement to choose between two different options. But, if you have multiple options to choose from, you can use the if...elif...else statement.

def main():

year = int(input('which year would you like to check?\n- '))

if year % 400 == 0 and year % 100 == 0:

print(f"{year} is leap year.")

elif year % 4 == 0 and year % 100 != 0:

print(f"{year} is leap year.")

else:

print(f"{year} is not leap year.")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# which year would you like to check?

# - 2004

# 2004 is leap year.

The elif statement usually goes after an if statement and before an else statement.

Think of it like "else if", so if the if statement fails, then the elif will take over. You write it exactly like a regular if statement.

Another new thing in this example is the and operator. It's one of the logical operators in Python. It does what it does in real life.

If the expressions on both sides of the and statement evaluates to true, then the whole expression evaluates to true. Simple.

Don't worry if you do not understand the and operator in detail at the moment. You'll learn about it and its siblings in the very next section.

Another thing you need to understand is that these if statements are just regular statements so you can do pretty much anything inside them.

def main():

number = int(input('what number would you like to check?\n- '))

is_not_prime = False

if number == 1:

print(f"{number} is not a prime number.")

elif number > 1:

for n in range(2, number):

if (number % n) == 0:

is_not_prime = True

break

if is_not_prime:

print(f"{number} is not a prime number.")

else:

print(f"{number} is a prime number.")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# what number would you like to check?

# - 10

# 10 is not a prime number.

This example is a bit more complex than what you've seen so far. So let me break it down for you. The program checks whether a given number is a prime number or not.

First, you take a number from the user. For a number to be prime, it has to be divisible only by 1 and itself. Since 1 is only divisible by 1, it's not a prime number.

Now, if the given number is larger than 1, then you'd have to divide the number with all the numbers from 2 to that particular number.

If the number is divisible by any of these numbers, then you'll turn the is_not_prime variable to True, and break the loop.

The break statement simply breaks out of a loop immediately. There is also the continue statement that can skip the current iteration instead of breaking out.

Finally, if the is_not_prime variable is True then the number is not prime, otherwise it's a prime number.

So as you can see, not only you can put loops inside a conditional statement but also put conditional statements inside a loop.

The final example that I'd like to show you is the for...else statement. As you can see in the example above, you have a for statement followed by a if...else statement.

def main():

number = int(input('what number would you like to check?\n- '))

if number == 1:

print(f"{number} is not a prime number.")

elif number > 1:

for n in range(2, number):

if (number % n) == 0:

print(f"{number} is not a prime number.")

break

else:

print(f"{number} is a prime number.")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# what number would you like to check?

# - 5

# 5 is a prime number.

If you put an else statement on the same level as a for statement, then Python will execute whatever you put inside that else block as soon as the loop has finished.

What are Relational and Logical Operators in Python?

In the examples above, you've seen the usage of == as well as the and operators. In this section, you'll learn about them in detail.

The relational operators come in handy when you want to check the relationship between two operands. There are six of these operators:

| OPERATOR | EXPLANATION | USAGE |

|---|---|---|

== |

Equal To | 5 == 5 gives you True, but 5 == 10 gives you False |

!= |

Not Equal To | 5 != 10 gives you True, but 5 != 5 gives you False |

> |

Greater Than | 10 > 5 gives you True, but 5 > 10gives you False |

< |

Less Than | 5 < 10 gives you True, but 10 < 5 gives you False |

>= |

Greater Than or Equal | 10 >= 5 and 10 >= 10 gives you True, but 5 >= 10 gives you False |

<= |

Less Than or Equal | 5 <= 10 and 5 <= 5 gives you True, but 10 <= 5 gives you False |

You've been using the equal to operator since the very beginning. The other ones you'll learn about as you keep going.

Apart from these, there are three logical operators in Python. They are the and, or, and not operators.

Take an RPG game, for example, where the hero has to have a level 45 or up shield and a level 48 or up sword in order to go to the next level.

def main():

shield = int(input('what is your shield level? '))

sword = int(input('what is your sword level? '))

if shield >= 45 and sword >= 48:

print('you shall pass!')

else:

print('you shall not pass!')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# what is your shield level? 42

# what is your sword level? 52

# you shall not pass!

Unless you meet both conditions, the statement will evaluate to False. You can have more conditions in a statement like this:

def main():

shield = int(input('what is your shield level? '))

sword = int(input('what is your sword level? '))

armor = int(input('what is your armor level? '))

if shield >= 45 and sword >= 48 and armor >= 25:

print('you shall pass!')

else:

print('you shall not pass!')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# what is your shield level? 45

# what is your sword level? 50

# what is your armor level? 10

# you shall not pass!

The or operator, on the other hand, is a bit more forgiving. If any of the given conditions evaluates true, than the entire statement will evaluate to true.

For example in another horror game, you can only get into The Castle Dracula if you are more than 500,000 years old or legally dead.

def main():

age = 10_000

is_legally_dead = True

if is_legally_dead or age > 500_000:

print('you shall pass!')

else:

print('you shall not pass!')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# you shall pass!

You can mix the and and or operators together. I won't list out all the possible combinations of these operators, but as you keep working with Python, you'll get to use a lot of them.

The last logical operator that I'd like to discuss is the not operator. This operator takes only one operand and returns the opposite value.

def main():

print('not True =', not True)

print('not False =', not False)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# not True = False

# not False = True

For example, if you change the rules of the horror game we talked about in the previous example and make is so that only people who are over 500,000 years old and not Van Helsing can enter the castle.

def main():

age = 800_000

is_van_helsing = True

if age > 500_000 and not is_van_helsing:

print('you shall pass!')

else:

print('you shall not pass!')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# you shall not pass!

Since we've been talking about conditional statements and some of the operators associated with them, I'd like to introduce you to another statement first introduced in Python 3.10, the match...case statement.

Since my colleague Kolade Chris has written such a nice article on the topic, I'll not repeat that here. Feel free to check it out at your leisure.

What Are Assignment Operators in Python?

You've already encountered the simple assignment operator which is the = sign you used to assign a value to a variable.

Now there are a few variations to this operator that you can use to perform arithmetic and bitwise operations while also assigning a value.

Bitwise operations are a little out of the scope of this book, so I'll stick to the arithmetic operations.

There are seven different assignment operators in Python. Since you've already learned about the simple one, I'll discuss the other six in the following table.

| OPERATOR | USAGE | EQUIVALENT TO |

|---|---|---|

+= |

a += b |

a = a + b |

-= |

a -= b |

a = a - b |

*= |

a *= b |

a = a * b |

/= |

a /= b |

a = a / b |

%= |

a %= b |

a = a % b |

**= |

a **= b |

a = a ** b |

These operators are not exclusive to Python, and in most programming resources, you'll find these in a much earlier chapter.

But I wanted to wait until you've learned about taking input from the user, working with ranges, and looping through them before introducting them here.

Assume that you want to write a program that calculates the sum of all the numbers within a given range.

def main():

start = int(input('which number do you want to start from?\n- '))

end = int(input('which number do you want to stop at?\n- '))

total = 0

for number in range(start, end + 1):

total += number

print(f"the sum of the numbers between {start} and {end} is: {total}")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

# which number do you want to start from?

# - 1

# which number do you want to stop at?

# - 10

# the sum of the numbers between 1 and 10 is: 55

I hope you remember that the ending number of a range() function call is exclusive. So I had to add a +1 with the ending number.

Otherwise it's a very simple range based for loop that adds each number to the total variable and prints it out once the loop has finished.

What Is the Set Type in Python?

So far you've learned about a number of iterable types such as lists, tuples, and also strings. There is another one known as a set. Let's look at an example:

def main():

numbers = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}